The fate of Rome and Egypt was decided off the coast of Greece. On the morning of September 2, 31 BC, two fleets faced each other near Actium, on the western coast. On one side, 250 Roman and Egyptian warships commanded by Mark Antony and his ally, Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt. On the other, 400 warships under the command of Octavian, another Roman consul. After hours of observation, Antony’s fleet launched an attack around noon. The confrontation, however, was short-lived. Almost the entire Egyptian-Roman fleet was destroyed within a few hours by Octavian’s galleys. By late afternoon, seeing the disaster, Cleopatra, followed by Mark Antony, decided to flee to Alexandria aboard their ships. The naval battle of Actium went down in history as the symbol of the end of the Roman Republic and the founding act of the Empire.

After his victory, Octavian would become Augustus, the first emperor of Rome. Ancient historians such as Plutarch and Cassius Dio, supported by the voice of the Senate, reported that the romance between Antony and Cleopatra—referred to as the “Egyptian” in Rome—was the cause of the conflict between these two illustrious Roman citizens. The reality, however, was more complex. To understand it, we must go back to the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC.

Upon Julius Caesar’s death, Octavian and Mark Antony divided power

After the murder of the imperator, Octavian—his great-nephew and adopted son—and Mark Antony—his most loyal general—formed a Second Triumvirate a year later to share power and the territories of the Republic. The young Octavian, just 19 years old, inherited the western part—Italy and Spain—while the 39-year-old Antony, strengthened by his past conquests in Gaul and Thessaly, claimed the lion’s share with Narbonese Gaul and the eastern provinces, from Greece to Libya. This unequal division created the first tensions.

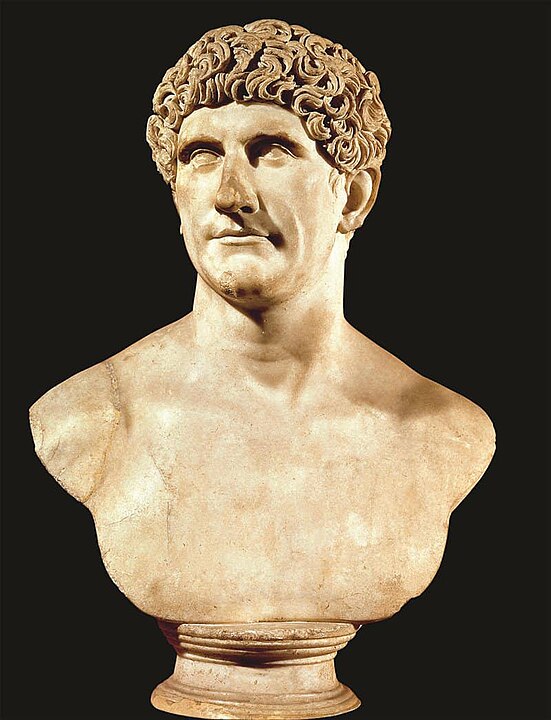

Everything already set the two men apart. Octavian, cold and calculating by nature, was an ambitious leader who wished to share nothing. Mark Antony was his opposite. Coming from an old Roman noble family, the gens Julia—a cousin branch of Caesar’s—he was nonetheless boastful and mocking. Passionate about Hellenic culture, especially its orgiastic celebrations, he had a reputation as a hedonist. In Parallel Lives, the Greek historian Plutarch described him as “a man with a virile appearance, strongly resembling the statues of Hercules.” Being a consul of Rome in the Greek world was, for him, a golden opportunity.

Queen Cleopatra Does Everything to Dazzle Mark Antony

Honored with this new title, Mark Antony traveled in 42 BC to Athens and then Asia Minor to organize the administration of his new territories. Very quickly, the question of Egypt arose. Its ruler, Cleopatra, had adopted an ambiguous stance after the assassination of Caesar, her lover. She had not condemned the masterminds of the plot: the Republican generals Cassius and Brutus. To Antony, she had to justify this behavior. To assert his authority, he summoned the queen to Tarsus, in present-day southeastern Turkey, rather than traveling to Alexandria himself. But Cleopatra was not a woman to bow easily.

She learned of the Roman’s passion for wine and women. Had he not once paraded drunkenly through Ephesus on a chariot, accompanied by young, naked slaves? To show him they were of the same kind, Cleopatra staged her entrance with equal grandeur. In Tarsus, in 41 BC, she orchestrated her arrival in the city, as described in detail by Plutarch: “She was seated on a golden stern, its purple sails seeming to fill the sky […] She lay beneath a canopy embroidered with gold, adorned like Aphrodite.” A meeting between the Greek goddess of love and Dionysus, the god of excess! To further their ambitions, they formed a political alliance rather than a mere love affair. The queen needed Rome’s power to secure her throne in Egypt. Mark Antony, in turn, sought to make Egypt the cornerstone of Rome’s eastern dominion.

During the winter of 41 BC, the consul joined Cleopatra in Alexandria. According to Plutarch, this stay marked the beginning of his downfall. The chronicler described a couple indulging in luxury, wandering the streets of Alexandria disguised as slaves. The consul also visited Egyptian temples, considered pagan by Rome. But could this not be seen as a way to respect local customs and thus make the Roman presence more acceptable to the Egyptian population?

Mark Antony also remained in Alexandria to prepare for a major offensive against the Parthians, a Persian-origin people threatening the East. However, Octavian forced him to return to the Senate for the renewal of the Triumvirate. Mark Antony retained control of the East but had to cede Narbonese Gaul to Octavian—a province he had previously ignored. This marked the second major conflict between the two men.

Mark Antony Marries Octavia, Octavian’s Sister

As a gesture of reconciliation, the master of Western Rome offered his sister, Octavia, to Mark Antony as a wife. Contrary to what some ancient authors claimed, this was a political move unrelated to the Egyptian queen.

The couple settled in Athens for three years. According to the Greek historian Appian, Mark Antony had no contact with Cleopatra during this period. At the end of the winter of 38 BC, another message from Octavian summoned him once more to Rome. Entangled in a conflict with a Roman general in the Mediterranean, Octavian accused Antony of failing to support him. Antony agreed to provide him with 130 ships in exchange for troops to defeat the Parthians. Octavian never kept his promise. A third crisis… Mark Antony dreamed of being a new Alexander the Great and failed to realize that the Triumvirate was merely a stepping stone for Octavian, who sought to unify Rome at any cost.

More than ever, the Roman ruler of the East needed Cleopatra. In this partnership, she was always in a position of strength. When she reunited with Antony in Antioch, in present-day Turkey, in 37 BC, she was granted territories such as Cilicia and Cyprus in exchange for the use of her armies, both on land and at sea. Rome was outraged—wrongly so. “Senatorial propaganda led people to believe that Antony had recklessly given away entire Roman provinces when, in reality, most were limited districts, such as ports in Phoenicia and Anatolia,” notes Maurice Sartre.

Caesarion, the Alleged Son of Caesar and Cleopatra, is Named “King of Kings”

The military campaign against the Parthians finally began in the spring of 36 BC, with mixed success. Antony seized present-day Armenia but failed to set foot in Syria. His conquest cost him 20,000 infantrymen and 4,000 cavalrymen. Yet, two years later, he celebrated a grand triumph upon his return to Alexandria.

Cleopatra was proclaimed “Queen of Kings.” But more significantly, Caesarion, the alleged son of Caesar and the queen, was named “King of Kings.” For Octavian, this was the last straw… What if this Caesarion ever aspired to rule Rome? His legitimacy posed a serious threat. He feared this representative of a Ptolemaic-Caesarian dynasty. What could be a more formidable rival than this bridge between Alexander the Great and Caesar?

Outraged by this coronation, Caesar’s great-nephew denounced Mark Antony as a “minion of Bacchus” before the Senate. Antony retaliated. From the palace in Alexandria, he accused Octavian of engaging in incestuous relations with the imperator. The insults escalated rapidly. Soon, the senators turned their ire toward Cleopatra. The lawmakers vilified “the foreigner” and portrayed her as a “sorceress” humiliating the virtuous Octavia.

Plutarch described her as an “arrogant and anti-Roman” woman, while the Latin historian Velleius Paterculus characterized Mark Antony as a “Sybarite under her influence, consumed by an ever-growing passion, and enslaved by the vices fueled by power, indulgence, and flattery.” The conflict could only end in a life-or-death struggle between Octavian, Mark Antony, and Cleopatra. The first act unfolded at the naval battle of Actium; the final act took place in Alexandria nearly a year later.

The Naval Battle of Actium Marks the End of the Roman Republic

Following their crushing defeat at Actium, Cleopatra and Antony returned to the Egyptian capital. The final months of these doomed lovers pose a challenge for historians, given the abundance of conflicting sources. Ancient authors have painted a romanticized picture of their demise: after living side by side, both supposedly committed suicide for love. The reality was far less poetic. While Antony secluded himself for months in a residence near the lighthouse, Cleopatra harbored a fantastical plan to establish a new kingdom in the East. But one by one, the eastern provinces pledged allegiance to Octavian, who sent his legions to Pelusium and Canopus in the Nile Delta.

Antony’s troops either surrendered or betrayed him. Plutarch recounts that Cleopatra corresponded regularly with Octavian to negotiate a possible surrender. Latin historians like Dio Cassius and Flavius Josephus interpreted these letters as a betrayal of Antony. But the master of Rome remained silent. Why negotiate? He held the upper hand and had no interest in being swayed. After all, the empire he sought to build needed Egypt’s immense wealth.

Cleopatra Commits Suicide Twelve Days After Mark Antony

At the beginning of the summer of 30 BC, the queen and Antony were finally reunited in the palace. They began constructing a mausoleum and held daily banquets. It came when Octavian arrived in Alexandria on August 1, after Antony’s futile attempt to defend the city, abandoned by his soldiers. Facing his rival, he took his own life. “Not out of love for the queen. Having lost the battle, he had no choice but to end his life, as was customary for generals,” explains Pierre Renucci.

Imprisoned in her mausoleum, Cleopatra took her own life twelve days later “to escape the execution Octavian had promised her during his future triumph in Rome—an intolerable affront for a Ptolemaic queen,” writes Italian specialist Roberto Angela in his book Cléopâtre (Harper Collins, 2019). But how did she die? Ancient and modern historians agree on at least one point: she was poisoned. The debate lies in whether it was due to a venomous snakebite or a toxic substance such as curare. Plutarch and Dio Cassius claim it was an asp’s bite, but in 2018, German scientists discovered traces of a liquid containing opium and hemlock on several royal mummies from that era… According to Roberto Angela, the legend of the snakebite may have been propagated by none other than Octavian himself: “During his triumph in Rome, he presented the crowd with a statue of the queen with an asp above her.”

The victor of Actium now faced only one threat: Caesarion, sent by the queen to Nubia. While awaiting the opportunity to eliminate him, the future emperor had all traces of Antony erased, from Alexandria to Rome, including Athens. In order not to offend the Egyptians, he organized lavish funeral rites for Cleopatra, whose tomb has still not been found to this day. The historian Dio Cassius wrote a sentence about the last queen of Egypt that reads like an epitaph: “Thus died the woman who dominated the two greatest Romans of her time and killed herself because of the third.” Who was this third? Octavian or Mark Antony?