This Article at a Glance

What is the oldest evidence of surgery?

The oldest evidence of surgery dates back to 31,000 years ago. Archaeologists on Borneo recently uncovered the remains of a young patient who had a healed amputation of his lower leg.

What did the Stone Age healer remove in the earliest successful surgery?

The Stone Age healer removed a child’s foot in the earliest known successful surgery. The left foot was not found throughout the excavation, and bone growth at the ends of the deceased man’s left tibia and fibula suggested that the damage had healed.

How did the Stone Age patient survive after the surgery?

The Stone Age patient must have lived for an additional six to nine years after the surgery. The fibula’s distal end was fully covered by new bone lamellae, indicating the bone grew again after the amputation. The wound was likely cleansed, dressed, and disinfected on a regular basis to avoid infection and alleviate discomfort, and the patient would have needed special care and nursing from the Stone Age community since he was immobile.

The oldest evidence of a surgery dates back to 31,000 years ago. This ancient skeleton’s missing left foot and ankle are no coincidence; the Stone Age guy had a successful amputation as a kid. A Stone Age healer removed a child’s foot and the patient lived. It was only recently that archaeologists on Borneo uncovered this oldest known surgery. They unearthed the remains of the young patient who had a healed amputation of his lower leg. According to the study published in Nature, he passed away between six and nine years after his procedure and was laid to rest in a karst cave. This discovery demonstrates the extraordinary sophistication of ancient hunter-gatherer healing practices.

Fossil evidence suggests that our ancestors utilized beeswax to alleviate toothache and tooth damage, as well as medicinal plants to address stomach issues and wound healing. Trepanations, high-risk surgeries in which the skull bone is pierced, have been documented as far back as the Neolithic (from 10,000 BC) and early Bronze Ages (from 3,300 BC). It is unknown, however, whether or not this was performed for ceremonial or therapeutic purposes.

Dead for 31,000 years

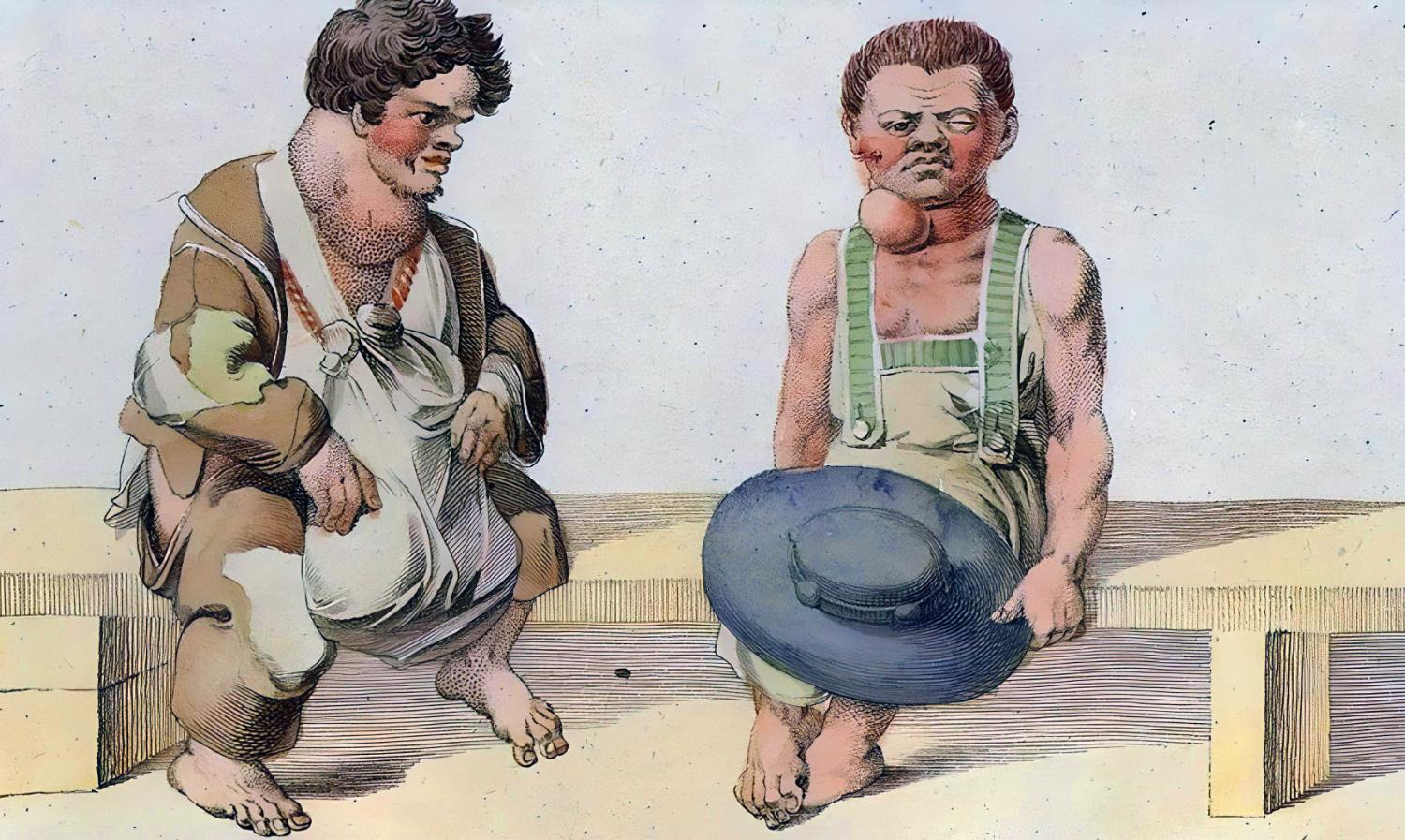

© Maloney et al./ Nature, CC-by 4.0

Recently, researchers discovered evidence of an amputation that took place 31,000 years ago, making it the oldest known surgical procedure from the Stone Age. East Kalimantan in Borneo is a karst area where rock paintings as ancient as 40,000 years and other evidence of early human existence have been uncovered. Tim Ryan Maloney of Griffith University in Australia and his colleagues made the discovery. Prehistoric rock art is also found in the top half of the three-chamber Liang Tebo Cave.

The crew discovered the tomb while digging in the cave’s main room, where the skeleton had been well preserved. A young adult guy, around 19–20 years of age, was TB1, a dead man who was found buried with flint knives and a chunk of red ochre. Charcoal and a bone sample dated by Maloney and his team revealed the age of this burial as about 31,000 years. This places it in the Paleolithic Era, the time of early farmers and gatherers.

Amputation of the left lower leg and foot

But what really sets it apart is the fact that the left foot was not found throughout the excavation. Bone growth at the ends of the deceased man’s left tibia and fibula suggested that the damage had healed. To put it another way, the prehistoric kid must have made it through without his foot and with just half a lower leg. The fibula’s distal end was fully covered by new bone lamellae. This means that TB1 survived its injuries for an additional six to nine years.

How did this young man of the Stone Age break his foot? Fractures usually result in splinters and bruises after blunt force trauma, such as an accident or animal assault; however, TB1 does not have these characteristics. Instead, the ends of the leg bones seemed to be cut in a straight line. This points to a surgical amputation of the lower portion of TB1’s lower leg, the oldest known surgery in history.

The Oldest Evidence of a Surgery

This data suggests that a brave healer from as early as 31,000 years ago performed this potentially life-threatening procedure. Thus, the skeleton discovered in Kalimantan’s Liang Tebo cave provides the earliest evidence of a successful surgical amputation or even surgery. Scientists previously reported that a Neolithic farmer in France had his left forearm surgically amputated some 7,000 years ago and that the wound had healed in part.

This successful amputation dating back to the Paleolithic Era not only reveals a previously unknown aspect of ancient human medicine but also provides fresh insights into the social and medical practices of our predecessors. The common belief up until recently was that hunter-gatherer societies lacked the technological sophistication to do such complicated tasks. Major surgery or long-term patient care was seen as incompatible with the nomadic lifestyle and lack of education. But it was wrong.

Remarkably Educated Primitive Doctor

(Jose Garcia / Griffith University)

The discovery of TB1 currently disproves these previous conclusions. Even in the late Pleistocene, the ‘surgeon’ needed an in-depth understanding of limb anatomy and the muscular and vascular systems to prevent deadly blood loss and infection. In order to keep the patient alive throughout this earliest operation, the surgeon must have carefully dissected the patient’s nerves, blood vessels, and other tissues.

In fact, there are no symptoms of serious infection in the amputation sites on the deceased man’s body, as this was common following an amputation before antibiotics were discovered. In order to avoid gangrene, the young boy would have needed special care and nursing from the Stone Age community since he was immobile. The wound was likely cleansed, dressed, and disinfected on a regular basis, maybe with the use of medicinal plants that were readily accessible in the area, to avoid infection and alleviate discomfort.

The child’s physique shows that he or she lived into early adulthood after the amputation but eventually healed from the injury. This says volumes about the quality of treatment and community support he had access to, especially considering the difficult topography of this karst area.

It’s the Oldest Surgery but It’s Hard to Consider It Primitive

Even though the discovery of this earliest surgery does not reveal whether cultures in this region generally possessed this level of medical knowledge or whether this operation represented an isolated case, the researchers believe that this was certainly the case. The discovery of this exceptionally old piece of evidence of intentional surgery in the tropical rainforest on the eastern edge of the Sunda landmass leaves much to be speculated about.

Our knowledge of this period in Homo sapiens’ history may also be limited by preconceptions regarding the ‘primitive’ nature of early medical and socio-cultural practices among non-sedentary populations in tropical Asia, but the researchers believe it is entirely possible that the people of the Stone Age rainforest of Borneo acquired and passed on the necessary knowledge and experience over the course of generations.

The research by Maloney and colleagues is significant because it provides a different viewpoint on early treatment and care. This study adds to the existing body of knowledge on the topic while also disproving the widely held belief that medical care was not an important factor in ancient societies.