After the conquest by Julius Caesar, the Pax Romana was established in Roman Gaul, which quickly became one of the most prosperous provinces of the Empire. Despite a few last revolts, the “Roman peace” settled under the principate of Augustus, and in two centuries, the landscape of Gaul transformed. The countryside became organized, the region adorned with new cities, and architects built roads and monuments. Romanization seemed complete. These two centuries of Pax Romana give an impression of prosperity: agriculture and crafts developed, and trade flourished. However, real difficulties slowly emerged, foreshadowing the major crises to come.

- Conquest of Gaul by Caesar

- Pax Romana in Roman Gaul

- Augustus’ Influence

- Resistance and Integration

- Transformation of the Gallic Rural Landscape

- The Gallo-Roman Villa

- Cities, Political and Cultural Centers

- Religions and the Christianization of Roman Gaul

- Commerce and Craftsmanship during the Pax Romana

- The End of the Pax Romana in Gaul

Conquest of Gaul by Caesar

Roman settlement in Gaul dates back to the late 2nd century BCE. At the time, Gaul was inhabited by a myriad of warlike Gallic tribes. Responding to a call for help from the Greek colony of Massalia, the Romans occupied it in 121 BCE and advanced along the coast toward their Iberian province and up the Rhône valley. They founded the colony of Narbonne, which became the center of the new and highly prosperous Roman province of the same name. To secure this province and consolidate his power in Rome, the Roman general Julius Caesar undertook the conquest of what was called “long-haired Gaul” in 58 BCE, which extended from the Pyrenees to the English Channel and the Rhine. The Gauls, united under the Arvernian leader Vercingetorix, were ultimately defeated during the siege of Alesia, following a war that lasted seven years.

Gaul slowly recovered from the ordeal of war and Roman conquest. Caesar then directed his policy in two directions: first, he planned, especially in southern Gaul, to settle former soldiers, veterans, in military colonies to ensure control of the country and serve as centers of Romanization. This was the case with Narbonne, Fréjus, Béziers, Arles, and Orange. Second, he secured the support of Gallic elites. Some had helped him during the conquest, while others supported him during the civil war against Pompey. He granted them Roman citizenship and gave them his name, Caius Julius. Thus was formed what has been called “a nobility of the Julii,” upon which his successor, Augustus, relied.

Pax Romana in Roman Gaul

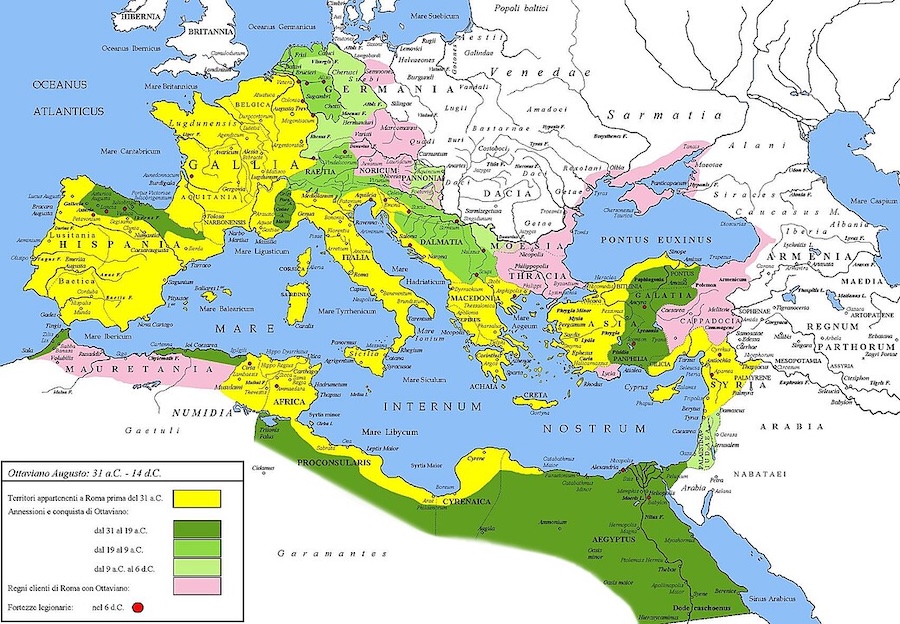

When Augustus, after defeating Antony at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, established the principate, he took care to promote certain ideological themes that inspired hope and confidence. The civil wars before Octavian, the future Augustus, came to power had been so long and deadly that it was essential to reassure the populations of the Roman Empire. Augustus promised peace and made this his political program. This was the Roman Peace, in other words, submission to Roman law. In Rome, the Altar of Peace was built to commemorate the final pacification of the Iberian Peninsula. In all the provinces, altars were also erected, reminding the provincials that the time of war was over and a new era, the Peace of Augustus, had begun.

The new emperor’s actions were evident in many areas. First and foremost, it was essential to pacify, which in reality meant suppressing by force the last centers of resistance that occasionally reignited. The emperor sent his son-in-law Agrippa, who in a few battles eliminated the opponents, particularly in Aquitaine. Augustus himself visited Gaul several times to quell the frequent unrest in border areas.

Augustus’ Influence

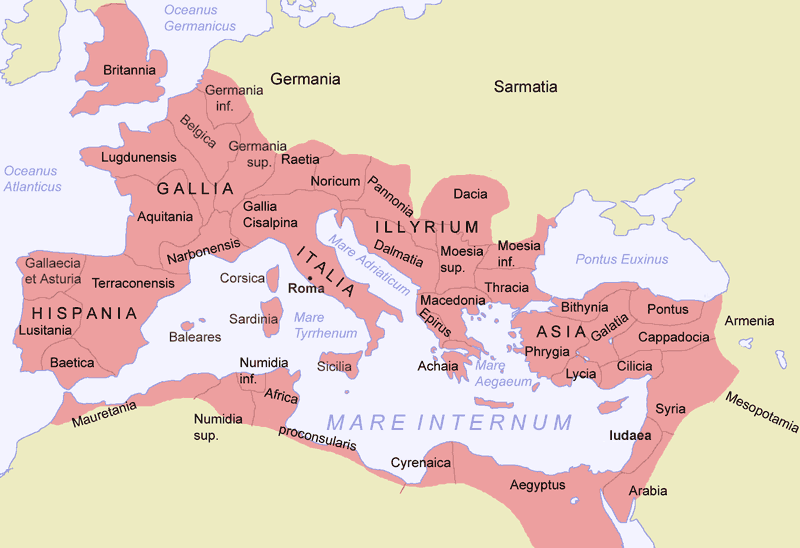

The territory was divided into provinces organized into two groups. On one side, the former province of Transalpine Gaul, bounded by the Pyrenees, the Cévennes, the Alps, and the Mediterranean, with the Rhône valley as its central axis, was now called Narbonese Gaul and remained under senatorial control, as it had been during the Republic. On the other side, the Three Gauls, made up of three provinces governed by legates appointed directly by the emperor: Aquitaine, with its northern border extended to the Loire; Lugdunensis, between the Seine, Loire, and Marne; and Belgica, covering the entire north of the country. Each of these provinces was divided into cities.

This group of the Three Gauls had a federal capital carefully nurtured by Augustus, located in Lyon. This site, long occupied by the Celts, saw the foundation of a Roman military colony in 43 BCE on Fourvière Hill: Lugdunum. The rapid growth of this colony was partly due to the commercial center developing at the confluence of the Saône and Rhône rivers.

But it was to Emperor Augustus that Lyon owed its political importance. The city was promoted to the capital of the Three Gauls. It became the meeting place for annual assemblies of delegates from all Gallic cities, where provincial matters were discussed. These assemblies, in another form, predated Romanization.

With remarkable political acumen, Augustus co-opted the former power structures of independent Gaul to serve his and Rome’s policies. He also made the city a central hub, as evidenced by the road network designed by Agrippa. From Lyon, major roads radiated out toward the north, northeast, and the Rhine frontier, eastward to the Alpine passes, southward to the Mediterranean, and westward to the Massif Central. Finally, Lyon became the capital of the official cult dedicated to Rome and Augustus.

The imperial cult was established early in municipal settings, as demonstrated by the Maison Carrée in Nîmes or the Temple of Augustus and Livia in Vienne. This cult strengthened the emperor’s power while also fostering the integration of the provincials.

Augustus also focused on southern Gaul. Urbanization, already well advanced in the 1st century BCE, accelerated thanks to numerous measures: the founding and strengthening of colonies, the granting of a more favorable legal status (Latin rights), and funding for civic works. He provided city walls for Vienne and Nîmes and subsidized the construction of theaters in Arles, Orange, and Vienne.

Resistance and Integration

However, Gaul in the 1st century AD was shaken by revolts whose aims are difficult to understand due to a lack of sources. The first of these revolts erupted under Tiberius in 21 AD, shaking the Pax Romana. These revolts are recounted by Tacitus, who highlights a particularly serious issue: debt. It was because they were burdened by heavy taxes and forced to go into debt that the populations of the Loire Valley, the Treveri, and the Aedui took up arms. Their discontent was even greater because they had previously enjoyed tax exemptions, which the Emperor Tiberius had to remove due to a severe financial crisis. These revolts, led by Romanized Gallic nobles, mostly broke out in the North and Northeast and were harshly repressed by Roman legions from the Rhine frontier.

Another revolt was fomented nearly fifty years later, in 69-70 AD, under very different conditions, as it was initially caused by a crisis affecting the imperial regime itself, weakened during Nero’s reign. However, within this complex movement, one can detect a clear expression of anti-Roman sentiment. It is known that Aedui peasants (eight thousand, according to the sources) followed a Celtic leader from Bohemia, Mariccus, who, speaking of Roman oppression, presented himself as the “liberator of Gaul.” The uprising had no further consequence, as Mariccus was arrested by the magistrates of Autun and executed. Nonetheless, it is significant because of the resonance it found in rural areas. Despite these sporadic resistances, the dominant sentiment was one of attachment to Rome, particularly within the ruling classes.

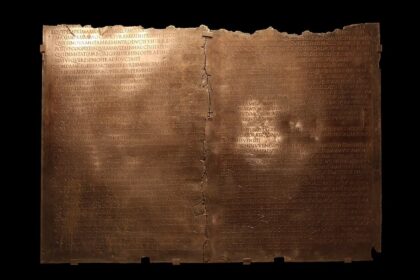

It is indeed in terms of integration that relations between Gauls and Romans were increasingly established, something the Emperor Claudius had understood very well. In a speech delivered in 48 AD, partially preserved in Lyon on a bronze plaque, he advocated for the Gallic nobles of the long-haired Gaul who wished to access imperial magistracies. Before a reluctant Senate, Claudius deployed all his knowledge and historical culture to demonstrate that Rome’s strength had always resided in its ability to welcome and integrate conquered peoples. After much hesitation, the Senate was convinced: integrating the Gauls would favor the development of the subjugated provinces.

Transformation of the Gallic Rural Landscape

Ancient authors tend to associate the development of the Gallo-Roman countryside with the Pax Romana: it was thanks to the peace established by the Romans that Gaul, naturally fertile, could devote itself to agriculture. This view is partial. Agriculture had already reached a remarkable level of development long before the conquest. However, it continued to grow during the Roman period due to more rational land use, increased productivity, and a deeper integration of production into trade networks.

The Romans exerted their influence over the rural population in two ways: first, they seized land to allocate it to former soldiers, Roman citizens who became full-fledged landowners within the colonies; second, they imposed a land tax, the tributum, on provincial non-citizens, an obvious mark of their subjugation. To establish colonies, count the population, and set the tax base, the Romans undertook a vast land surveying effort, the traces of which can still be observed in some areas of the present-day landscape.

On hundreds of hectares, they marked out large squares of 710 meters per side, delineated by roads, paths, or boundary markers. Properties within these large squares—called centuries—were delimited, identified, and allocated. All the information was then recorded and archived by specialized administrative services, as evidenced by the fragments of the land registry from the colony of Orange.

The Gallo-Roman Villa

The pre-Roman Gallic agricultural estates were replaced by large rural estates, known as villae, which were self-sufficient but also engaged in trade, as evidenced by pottery and jewelry found during excavations. The villa was a production unit consisting of agricultural land, the residence of the landowner (the villa in the strict sense), and outbuildings and workshops: a forge, carpentry shop, mill, brewery, weaving workshop, and, in southern estates, a winemaking facility.

The size of the estates varied significantly, influencing the modes of exploitation. It is likely that on estates of 50 to 100 hectares, direct farming with a predominantly servile labor force, a common practice in the South, was used. On very large estates, tenant farming or sharecropping was employed. The dominance of large estates should not overshadow the fact that the countryside was also inhabited by native villages and hamlets.

Under these conditions, exploitation took on very diverse forms. Alongside subsistence farming, speculative production developed, particularly on the villae, benefiting from the technical improvements introduced by the Gauls: the plow with a metal share, the wheeled plow, the harvester, various crop rotation practices, and fertilization. There was a marked increase in productivity, allowing for the production of surplus goods for commercial sale.

The North focused on cereals (wheat, millet, barley) and textile plants (flax, hemp), which were sold in the Rhine region. The South increasingly turned its production towards olive cultivation and, above all, viticulture. The latter expanded greatly during the 1st century and spread to Burgundy and the banks of the Moselle. With well-adapted grape varieties and efficient winemaking techniques, Gallic wines circulated within the country and the Mediterranean Basin. This rural development was closely linked to the extraordinary growth of urbanization.

Cities, Political and Cultural Centers

The establishment of municipal structures by the Romans was accompanied by a considerable expansion of urbanization. This effort was particularly focused on the Three Gauls, where cities were almost non-existent. The chosen sites were often located in plains near oppida: such as Clermont-Ferrand at the foot of Gergovia and Autun near Bibracte.

Contrary to a somewhat simplistic view, Gallo-Roman cities were not built according to a rigid, imposed Roman model. It is pointless, for example, to insist on finding a regular orthogonal plan. Where circumstances allowed, a grid layout was used, but this was not the primary concern for builders. The essential aim was to equip the city so it could serve as a political, administrative, economic, and religious center. The heart of the city was occupied by the forum, a large square around which the main public buildings were situated: the curia, basilica, temples dedicated to official gods and the emperor.

These political centers, with their porticoed forums like Ruscino, and colonnaded temples like those in Nîmes and Vienne, had a grand and theatrical character that seemed to appeal to these small provincial towns. Alongside these public life centers, which everywhere reflected the influence of Rome, the numerous leisure and relaxation buildings demonstrated the importance of collective life.

Among these buildings, the baths, theaters, and amphitheaters still impress with their size and capacity. The theater in Autun could hold 38,000 spectators, while the amphitheater in Arles accommodated 28,000 people, and the one in Nîmes, 24,000. The density and scale of these monuments, designed to enhance urban life and foster social gatherings, prove that they attracted not only the city’s population—typically around 8,000 to 10,000 inhabitants—but also the surrounding region’s people.

Religions and the Christianization of Roman Gaul

The religious landscape of Roman Gaul was exceptionally rich. The imperial cult, associated with Rome, does not seem to have had a significant impact on the Gauls: many Gaulish beliefs and practices continued, with major Celtic deities still being venerated and indigenous sanctuaries remaining active. However, contact with the Romans expanded the pantheon, enriching and diversifying the iconography, and leading to the development of unique syncretisms. Furthermore, from the 1st century onwards, salvation cults from the East, such as the cults of Cybele, Mithra, and Christianity, began to spread along trade routes, in cities, and in frontier regions. The rise of these spiritually and emotionally charged religions reflected growing anxieties during difficult times.

By the 2nd century CE, Christian presence was noted in Lyon and Vienne, among communities from Asia Minor. After the persecutions of 177 CE, Bishop Irenaeus wrote the first Christian texts in Gaul. Evangelization of Gallic cities became very active in the 3rd century, thanks to various bishops such as Denis in Lutetia, Trophimus in Arles, Martial in Limoges, and Saturninus in Toulouse. Unlike the cities, the countryside remained attached to pagan worship, and it was not until a hundred years later, with Saint Martin, bishop of Tours, that they began to fully convert. The massive conversion of Gaul only occurred under Constantine, the emperor who established Christianity as the official religion throughout the Empire in 312 CE.

Commerce and Craftsmanship during the Pax Romana

In cities, all trades and crafts were represented. Traditional woodworkers, such as carpenters and coopers, were well-known through their large guilds, which had a religious aspect; metal trades have left enough artifacts—arms, vases, jewelry, and coins—to attest to the skill of founders, blacksmiths, and bronze workers. Stoneworking was more recent, as the Gauls had little stone architecture, but they quickly became excellent builders, with quarrymen, stonemasons, and bricklayers active in the numerous construction sites across Gaul.

However, it was perhaps in pottery and glasswork that the Gallo-Romans reached their greatest mastery. Gallic potters, already numerous and skilled during the period of independence, quickly adopted manufacturing techniques from Italy, particularly from Arezzo. They produced red-slipped pottery called sigillata, from the word sigillum, referring to the stamp with which they signed their wares. Centers of sigillata production multiplied in the Southwest at La Graufesenque, Montans, and Banassac, in the Center at Lezoux, and in the Northeast. This pottery fueled a thriving trade in Gaul, Italy, and the provinces.

Solid glass had long been used by the Gauls for jewelry (bracelets, necklaces), but during the Roman period, the spread of glassblowing techniques enabled glassmakers to create, with incredible boldness, flasks, bottles, and goblets in a wide variety of shapes and colors.

This artisanal production, along with agricultural products, fueled local, regional, and international trade. Lyon, Narbonne, Arles, and, to a lesser extent, Bordeaux, became major commercial centers, though all cities engaged in trade of raw materials (lead, copper, tin), agricultural products (wheat, wine, olive oil), textiles, and manufactured goods (ceramics, glassware).

Trade routes had definitively lost their colonial character from the Republican era. Consumers exhibited diverse needs and benefited from a relatively flexible market and a general rise in living standards. The wine trade is a good example: while Gaul exported large quantities of wine, especially to Italy, it simultaneously continued importing Italian wine.

Why? It was because the wines were of very different qualities: Gallic wine was an ordinary wine, mainly intended for the population of Rome, which was a heavy consumer, while Italian wine imported into Gaul was of a quality reserved for a wealthy clientele. Similar observations can be made for the oil trade. These lucrative activities were managed by specialists, the negotiatores, who were well-known in Lyon and Narbonne. Within their powerful guilds, linked to transporters and shipowners, they were regarded as prominent figures.

The End of the Pax Romana in Gaul

Life in Gaul during the first two centuries CE conveys an impression of peace and prosperity. In all sectors of economic life, activity was intense, and by the end of the 2nd century, resistance seemed definitively subdued. Gaul, protected by strong fortifications along the Rhine, appeared capable of withstanding the fearsome Germanic incursions. Yet some cracks were already appearing: city budgets were increasingly in deficit, peasants were agitating against the accelerating land concentration, and the state itself, under the reigns of Marcus Aurelius and Commodus, was shaken.

By the 3rd century, Gaul faced both the military anarchy that destabilized the Empire and the first barbarian invasions. Despite occasional periods of respite, the Roman Empire collapsed in the 5th century, and with it, the Pax Romana. Roman Gaul would survive in the new kingdoms founded, notably that of the Franks.