“It was the most significant upheaval that had ever shaken the Greek people, some of the Barbarians, and almost the whole human race.” Thucydides, an Athenian historian, provides a keen analysis of the origins and developments of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), a conflict that pitted Athens and Sparta against each other for a total of 27 years with support from their respective allies. For his failure to defend Amphipolis in Thrace from the Spartans in 424 BC, he was exiled from Athens as a strategist (military general). Thucydides used the time he spent in exile to compile his work, in which he blamed Athenian imperialism, which had become increasingly powerful since the Greco-Persian Wars of the early 5th century BC.

Athens’ intolerable interference

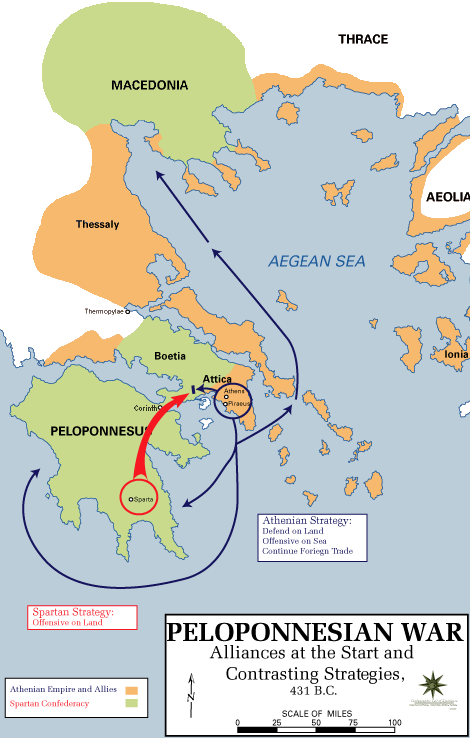

It was true that during the Pentecontaetia period (478-433 BC), the Athenians organized a vast territory in the Aegean that served their economic interests and was maintained by force. Established in 478 BC to continue the fight against the Persians, the Delian League was initially an egalitarian alliance between some 200 Greek cities, which chose Athens as leader with least initial submission at the outset. However, the league and its powerful fleet quickly became instruments in the service of the Athenians’ ambitions, financed by a tribute initially kept on the island of Delos.

The “Athenian empire” established by Cimon and later Pericles included five districts around the Aegean Sea that all used the same drachma coin depicting an owl of Athens (Athena). Even the mildest attempt at secession was violently put down by the Athenians. Samos paid the price in 440 BC when it was forced to hand over its fleet, destroy its walls, and watch as its generals were tortured in the name of the ruthless Pericles who had left his mark on the history.

Sparta delayed its response to Athens until the Peloponnesian League gathered in 432 BC, after a number of local skirmishes had already occurred. Corinth’s game of alliances and pressure, combined with Athens’s meddling and Sparta’s wait-and-see attitude, pushed the Greek world into a violence war that still shock contemporary historians.

Sparta and Athens fought for a decade without either side ever coming out on top. When the “Peace of Nicias” was signed in 421, the pacifists had won.

A third of Athens’ population was wiped out at the start of the war when a typhus epidemic spread from the port of Piraeus. According to historical records, Pericles passed away in 429 BC. All Athenians, urban and rural alike, were gathered behind the city’s fortifications, the “Long Walls,” to create an impregnable island, supplied by sea, which did not help the health situation at the outset of the conflict. The allies of Athens, especially the rebels, suffered from the war’s consequences as well. Mytilene, a city on an island, attempted to secede from the Delian League in a rebellion in 428 BC.

The Athenians responded quickly by placing a siege on the city of Mytilene in an effort to send a message to any potential future defectors. Fortunately, a trial arrived just in time to prevent the execution of all the men and the enslavement of the women and children; overcame with guilt, the Athenian assembly declared that it had changed its mind and commuted the sentence. Mytilene must dismantle its defenses and hand over its navy and some of its land. For those who were against democracy, this about-face demonstrated the system’s vulnerability.

Finally, the fighting continued at various locations until 421 BC, with neither side able to claim victory. Cleon the Athenian and Brasidas the Spartan, the two main war-mongering generals, both died in 422 BC during the clashes in Thrace, contributing to the growing fatigue of the conflict. In 421 BC, the two sides signed the Peace of Nicias for a theoretical period of 50 years.

But the program of peace advocated by Nicias, an old and wise man, was challenged by the ambitions of a young aristocrat in full bloom. The assembly of Athens decided to send a fleet to Sicily in the spring of 415 BC after hearing Alcibiades’ fiery imperialist harangues. The expedition was doomed to fail. The Athenians fought against Selinunte because they wanted to find a breadbasket and expand their influence to the west, both of which could be achieved by conquering Segesta.

Religious scandals rocking Athens

Again, the Peloponnesian War got off to a bad start for Athens, a city the gods appeared to have abandoned (and rightly so): two major sacrileges rocked the city in the midst of military preparations. The Athenians discovered to their horror one morning in May or June of 415 BC that their city’s hermes had been mutilated.

These hermes were marble pillars that could be found all over Athens, guarding the city’s crossroads and the entrances to people’s homes. During the course of Athenian justice’s questioning of dozens of witnesses, a second religious scandal was revealed through depositions: slaves claimed that in their masters’ house, young aristocrats were having fun parodying the Eleusis mysteries, a secret initiation rite dedicated to the goddesses Demeter and Persephone, while slightly inebriated.

Alcibiades, who was embroiled in the scandal, defected to the Spartan side rather than return to Athens to explain himself. The staunch defender of war betrayed his country and became its enemy.

Alcibiades was now one of the names mentioned. Although Alcibiades had already left for Sicily with fellow strategists (or strategos) Nicias and Lamachus, he was now required to return to Athens to give an account of his actions and face judgment. But he tricked his escort on the way back and hid out in, Sparta! Alcibiades even betrayed his country by advising the Lacedaemonians to fight for Sicily (the Sicilian Expedition, BC 415-413).

The Sicilian Expedition developed rapidly into the Athenians’ worst nightmare. Several thousand lives were lost, and much of Athens’ fleet was annihilated, due to the events in Sicily, which had weakened the city. Eventually, some of its allies switched sides and joined the Spartans. This was the political climate in which the Athenian democracy was overthrown.

The council of Boule, the model of democracy at the time, was disbanded by the new government of the Four Hundred in 411 BC, making way for an oligarchy limited to a few thousand citizens. This policy of the oligarchs, led by men like Antiphon the Sophist and Theramenes, did not last long in the face of a resurgence of the democratic forces garrisoned near the island of Samos.

A few months later, with the help of General Thrasybulus and Alcibiades, the oligarchic regime fell. Since the latter was already a father through his relationship with Agis II’s queen, he was in a rush to leave Sparta and sought out the Persian monarch at first. The incumbent oligarchs failed to recall Alcibiades to Athens, so he sought out the democratic opposition, who gladly accepted him, seeing in him a useful strategist.

This is where Thucydides’ account ends and the historian Xenophon picks up the rest in his book Hellenica.

Death knell for the Athenian Empire

The situation in Athens hadn’t improved much despite the return of democracy. In the end, the Spartans realized that they could only defeat Athens for good by taking the battle to the sea. Athens, the great thalassocracy, had to face the Spartan fleet that was formed after Lysander, the Spartan fleet’s general, negotiated with Cyrus the Younger, the Persian army’s commander in Asia Minor. Thus, the fate of Athens was decided at sea: the naval Battle of Aegospotami, which occurred at the end of the Peloponnesian War in 405 BC, sounded the death knell for the empire.

Athens was already feeling the effects of its fleet’s defeat because Lysander, who owned the road to the corn supply, had organized a food blockade. When pressed for food, the Athenians negotiated with the Spartans, who presided over a congress of the Peloponnesian League in 404 BC, where the city of Athena’s fate was hotly debated.

While the Corinthian and Theban peoples would have liked to see Athens wiped off the map entirely, Sparta was firmly against the idea because it threatened its own power and the potential rise of Thebes, which was located further north.

The Athenians, fearful of receiving the same treatment they had meted out to other cities, signed a treaty that spared them at the cost of relinquishing the symbols of their power: the Long Walls, the fleet, and the empire. Once again, the situation worked in favor of the Athenian oligarchy: in 404 BC, the government of the Thirty, backed by Lysander and the Spartans stationed in the city, imposed unprecedented terror. Almost 2,000 people lost their lives during this tragic time in Athens.

However, the Spartan victory did not mean the end of hostilities. The government of the Thirty, a tyrannical and bloodthirsty group, also toppled the Athenian democracy as a result.

Critias, Plato’s cousin, and Theramenes, were the worst of the worst among this group of bloodthirsty oligarchs, and they were pushed to their deaths by their extremist compatriots who viewed them as too moderate. It wasn’t until 403 BC that democratic forces successfully resisted and reinstated the system.

The war cost Athens dearly, with the collapse of its empire and two oligarchic revolutions, but the city entered the 4th century BC with a revived and strengthened regime, which would not experience any further shocks until the arrival of the Macedonians. Surprisingly, it appears that Sparta, the victorious city, was the most traumatized by the fighting.

Lysander takes power in Sparta

The war only made the already fragile Spartan system much more unstable. Sparta was already suffering from a severe population decline after the earthquake of 464 BC, and the loss of its soldiers only added to their distress. The Lacedaemonians’ tradition had always been to die heroically in battle rather than face the social disgrace of defeat, so the Greeks were shocked when 120 surrounded Spartans surrendered to Cleon on the island of Sphacteria in 425 BC (Battle of Sphacteria). The myth was destroyed.

The Spartans’ helot slaves filled in for the missing hoplites as a result of their oliganthropia (“lack of men”). General Brasidas therefore set out in 424 BC with 700 helots to conquer the Thrace city of Amphipolis. For their loyalty, these garrisons stationed at Sparta’s borders were granted limited freedom in exchange for full citizenship.

At the same time, however, Sparta vanished 2,000 helots away out of fear of a rebellion by slaves it had armed, acting as a counterweight that ultimately seals the doom of the freed “Brasidians.” Therefore, Sparta was confronted by both internal social and demographic upheavals and external challenges.

The appearance of Lysander, a Spartan mothax (one who was too poor to be a full citizen), did serve as a symbolic marker of the Peloponnesian War’s conclusion. But he rose to the position of navarch (chief of the fleet), and the initial sympathy of the cities “freed” from the Athenian yoke was attributed to the aura of his victory over Athens.

In a short amount of time, however, Lysander tainted the glory of Lacedaemonia with the blood of his excesses: after installing authoritarian and violent governments in several cities, he was recalled to Sparta out of concern for his behavior.

Throughout Greece, people celebrated his life with festivals called Lysandreia established in Samos; no other living man had ever been given so much recognition. This was too much for the traditionalists in Sparta, who looked down on the general’s autonomy and dislike his foreign policy.

Plutarch claimed that the Spartans were fundamentally corrupted during the Peloponnesian War. He claimed that the influx of Persian gold brought about by the negotiations between Lysander and Cyrus the Younger shook another pillar of the myth: austerity and the refusal of the currency.

Sparta, with fewer than 2,000 citizens and suffering from Lysander’s reputation as a tyrant, enjoyed a bittersweet victory. After its victory over Athens, the city was the site of a failed conspiracy in which a certain Cinadon rallied many people who felt excluded from Sparta’s political and social life. So the city’s reign as a power was brief; in 371 BC, Thebes usurped the throne.

TIMELINE OF PELOPONNESIAN WAR

- 431 BC – After the Spartans invaded Attica, its citizens fled to Athens for safety. Expedition from Athens to the coast of the Peloponnese.

- 430 BC – The Athenians were trapped inside the city walls when a plague epidemic broke out. There was a mass death that claimed one-third of the population, including Pericles.

- 425 BC – In 424 BC, the Athenians won at Pylos and Sphacteria; then the Spartans and Thebans won at Amphipolis and Delion.

- 421 BC – Exhausted from the war, both sides agreed to a 50-year ceasefire, known as the Peace of Nicias.

- 415-413 BC – An Athens expedition to Sicily ended in disaster as a result of poor planning. The Athenians had been doomed ever since this defeat.

- 412 BC – Lysander, a Spartan general, and Cyrus, a Persian prince, formed an alliance that ultimately decided the war.

- 404 BC – The beleaguered and impoverished city of Athens surrendered after the defeat of the Battle of Aegospotami (405 BC).

War crimes in the Peloponnesian War

Soldiers were also hit hard by the escalation of violence. For instance, the Athenians severed the right hands of their prisoners before the Battle of Aegospotami in 405 BC, and Admiral Philocles had the crew of the two enemy ships thrown overboard. The victorious Spartans exacted their vengeance on Athens at Aegospotami, where they massacred three thousand prisoners, including Philocles.

In 413 BC, after the Athenians were defeated in Sicily, their ally and victorious enemy Sparta imprisoned 7,000 of them in the quarries of Syracuse. There, they subsisted on 500 grams of food and a quarter liter of water each day. Many people perish as a result of exhaustion, illness, and lack of shelter. The combined odor of their decomposing bodies and the feces was intolerable. Those still alive after 70 days were sold into slavery.

Refugee tragedy during Peloponnesian War

Large numbers of people were forced to seek refuge after civil uprisings and sieges. Defeated groups’ members, if they had families, had to leave the city. Also, men who fled for political or criminal reasons were sentenced to death in absentia and had their possessions seized.

The oligarchs fled to the cities of the Peloponnesian League, while the democracies sought refuge in the cities of the Delian League. Afraid for their lives, they went to places of worship, holy forests, or sanctuaries and assumed the posture of the beseeching worshipper. However, their enemies did not always acknowledge the divine shield. While some were able to afford rent, the vast majority ended up living in makeshift camps due to financial constraints.

Human casualties

The Peloponnesian War had caused an unprecedented number of casualties. Milos and Scione were two cities that suffered total male fatalities. When the conflict began, Athens was hit by a plague epidemic that killed nearly a third of the city’s population, causing it to suffer the greatest casualties of any city. More than half of the Athenian male population had been killed by the Peloponnesian War’s end.

Bibliography:

- Heftner, Herbert. Der oligarchische Umsturz des Jahres 411 v. Chr. und die Herrschaft der Vierhundert in Athen: Quellenkritische und historische Untersuchungen. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2001 (ISBN 3-631-37970-6).

- Hutchinson, Godfrey. Attrition: Aspects of Command in the Peloponnesian War. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Tempus Publishing, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 1-86227-323-5).

- The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War, edited by Robert B. Strassler. New York: The Free Press, 1996 (hardcover, ISBN 0-684-82815-4); 1998 (paperback, ISBN 0-684-82790-5).

- Roberts, Jennifer T. The Plague of War: Athens, Sparta, and the Struggle for Ancient Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017 (hardcover, ISBN 978-0-19-999664-3