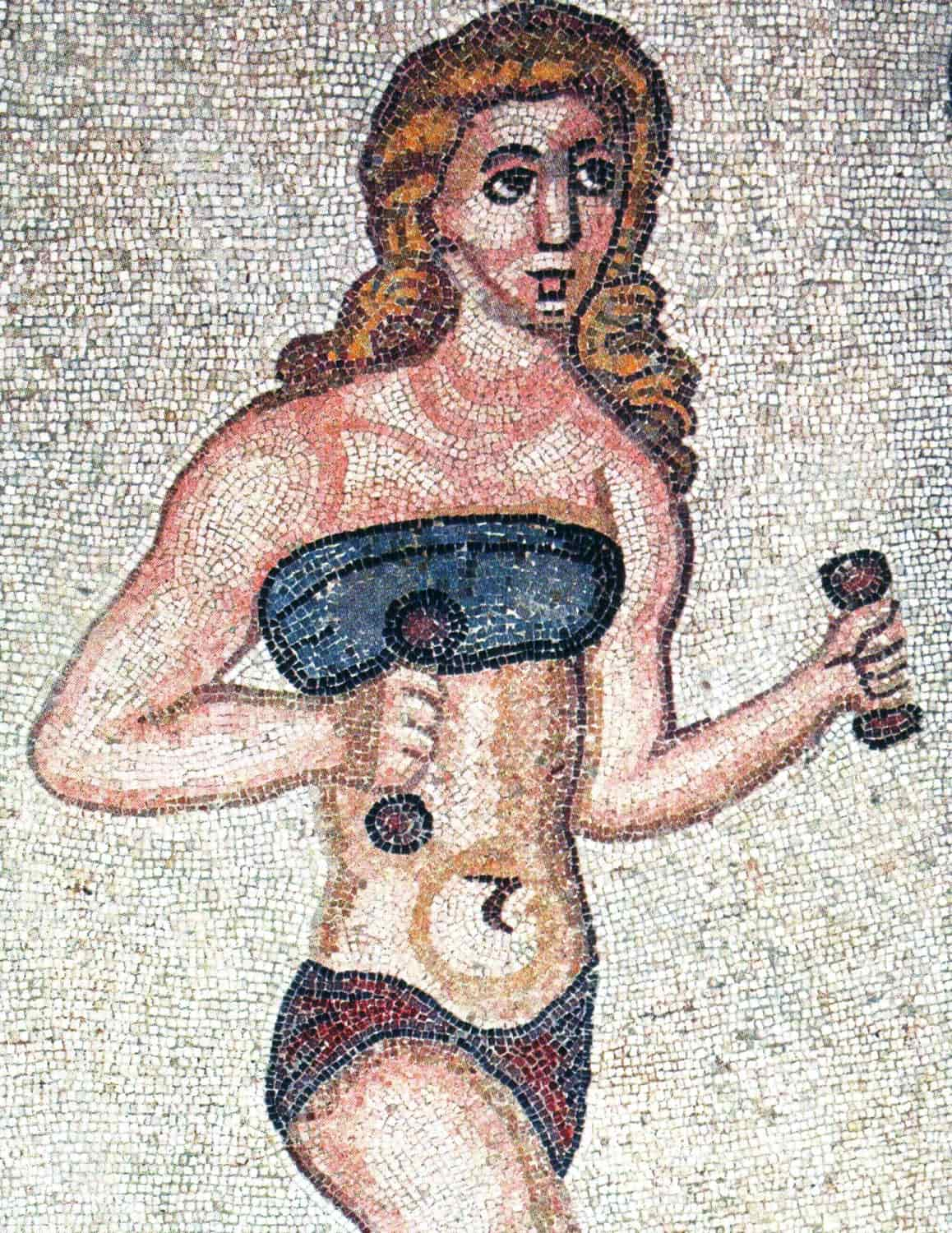

- Ancient loincloth used as underwear, documented in Minoan culture.

- Mentioned in relation to Jesus’ crucifixion, but not historically accurate.

- Theological debates influenced its representation in Christian art over centuries.

The perizoma was a kind of loincloth used as underwear in antiquity. The word comes from Greek: περίζωμα which means around the waist. The Minoan culture of Crete is where its existence was first documented. The perizoma is also a reference to the fabric that covered Jesus on the crucifixion, also called the loincloth of purity.

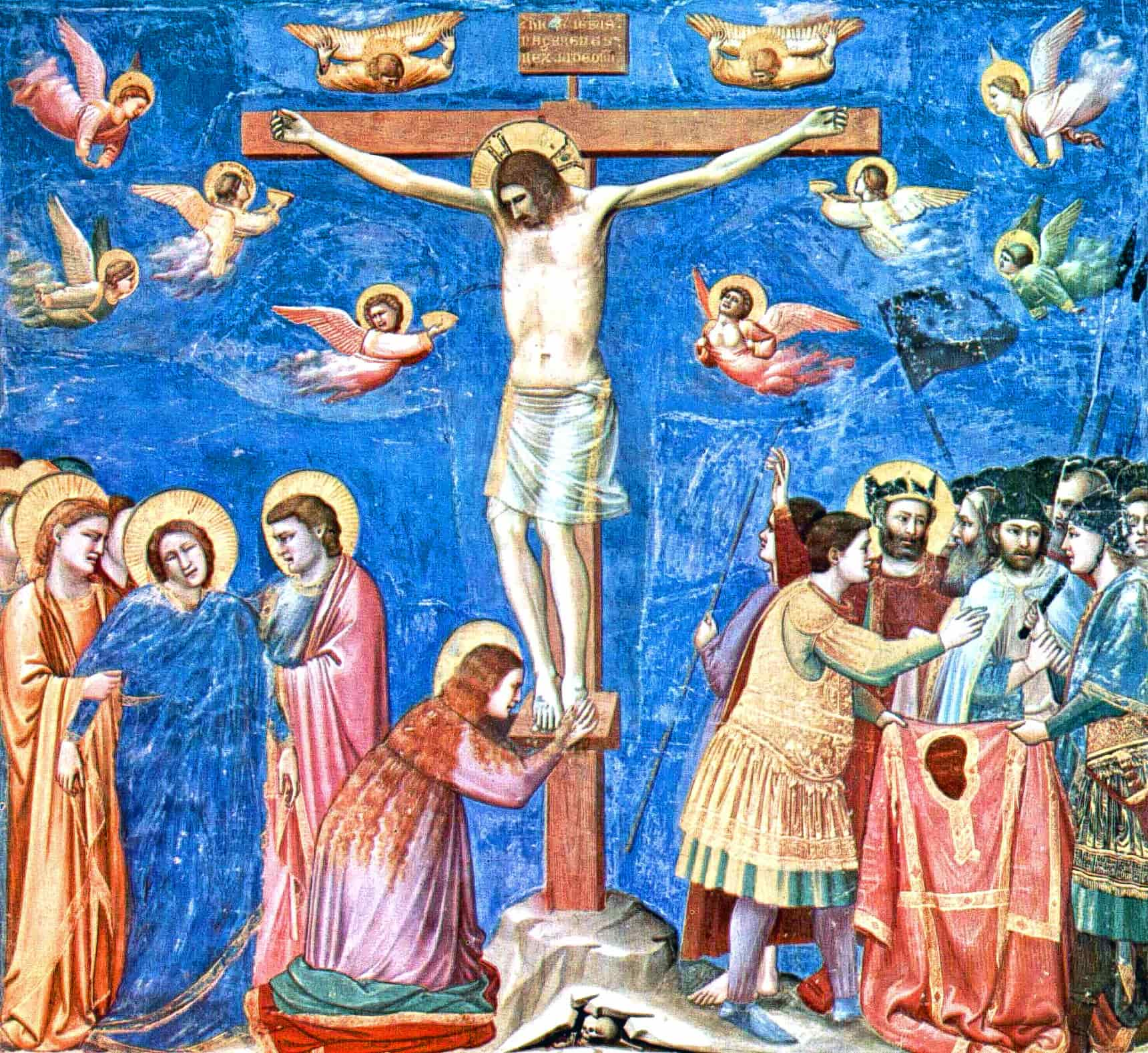

Perizoma and the Crucifixion of Jesus

During Jesus’ crucifixion, the Roman soldiers probably stripped him down to his linen underwear. However, it’s not probable that they draped a loincloth over him out of regard for Jewish modesty. Flagellation, in which the victim is stripped completely naked, was the ultimate Roman humiliation.

Before the 8th century, the perizoma was not shown in art.

The fourth-century Gospel of Nicodemus makes mention of this quality:

“Jesus left the praetorium accompanied by the two [impenitent] thieves. When they arrived, they stripped him of his clothes, put a cloth around him, and placed a crown of thorns on his head.”

Perizoma as an Heirloom

The fabled Descriptio recounts how the ruler of Constantinople allegedly presented Charlemagne with Passion relics upon his return from Jerusalem. The Holy Lance and the perizoma were also there, as were a nail and a piece of wood from the True Cross.

The virgin’s clothing and Jesus’ swaddling garments were both revered artifacts. The perizoma is the only relic now housed in Aachen Cathedral. Charles the Bald relocated the others in 876 to the royal abbey of Saint-Denis and the church of Saint-Corneille in Compiègne.

The perizoma may represent Christ’s girdle, length, and other characteristics, making it a useful tool for dating crucifixion art.

The Fate of the Naked Jesus Figures

To emphasize his vulnerability, early painters often showed Jesus without clothes on. A colobium (lengthy tunic) or subligaculum (an ancient Roman undergarment in a thin strip of cloth like a thong) is what Jesus was often shown wearing when he began to be represented in Rome in the 5th century. This was despite the fact that it was Roman custom to crucify people bare-naked.

Throughout the century, this almost-naked, crucified man image, which dates back to the Hellenistic era, faded from view in the 500s. In 593, Gregory of Tours wrote about a dream in which Christ came to a priest called Basil, condemning his nudity and threatening him with death if he did not cover it up. This dream is recounted in Glory of the Martyrs.

A colobium became a common iconographic theme in Eastern places vulnerable to monophysite influence; therefore, it has become common to see Jesus wearing a long tunic in his newer depictions. Because of this religious ban, depictions of Christ in his naked, simplified form have become uncommon in Christian art since the 11th century.

The Rise of the Perizoma

The claim that two Roman soldiers wore Christ’s clothing as their own sparked discussion in the Middle Ages. As time went on, painters stopped using the colobium in favor of the perizoma, starting about the 8th century.

In the 11th century, the perizoma reached its peak, giving rise to a variety of drapery styles, some of which assumed striking proportions in Romanesque art. Perhaps this represented a popular myth at the time that Mary ripped off a portion of her robe to hide Jesus’ nakedness at the foot of the cross.

Around the end of the 13th century, the Italian artist Giotto painted a translucent perizoma. Perhaps he mirrored the famous religious artifact, the Virgin’s Veil of Mary. However, this may also be an allusion to Augustine of Hippo’s rejection of Christ’s potentia generandi (“sexual power”) since the translucent perizoma shows Jesus with a sexual trait. The perizoma reverted to its original opaque state in the 14th century.

The initial theological justification for the “ostentatio genitalium,” or display of Christ’s genitalia, was to emphasize his humanity. However, his nudity was banned during the Council of Trent and the Catholic Reformation; therefore, this movement met resistance. These two groups disapproved of the concept that religious art should once again emphasize beauty and the nakedness of classical antiquity.

Plaster or lead perizoma (used for censorship) was applied to his statues, while opaque and subsequently transparent perizoma (used for censorship of paintings) were also used for this purpose. As the linen got increasingly see-through, the sex of Christ on the crucifixion became less obvious. Like the virtuosic lightness of the linen, it was selected to subtly but powerfully imply that Christ lacked the virile quality or was only gifted with a little, boyish sex.

However, there were instances of Christ being completely unclothed in depictions of the Passion even during the Renaissance era, as seen in Michelangelo’s well-known youth crucifix. Nonetheless, all of these efforts were just austere devotion.

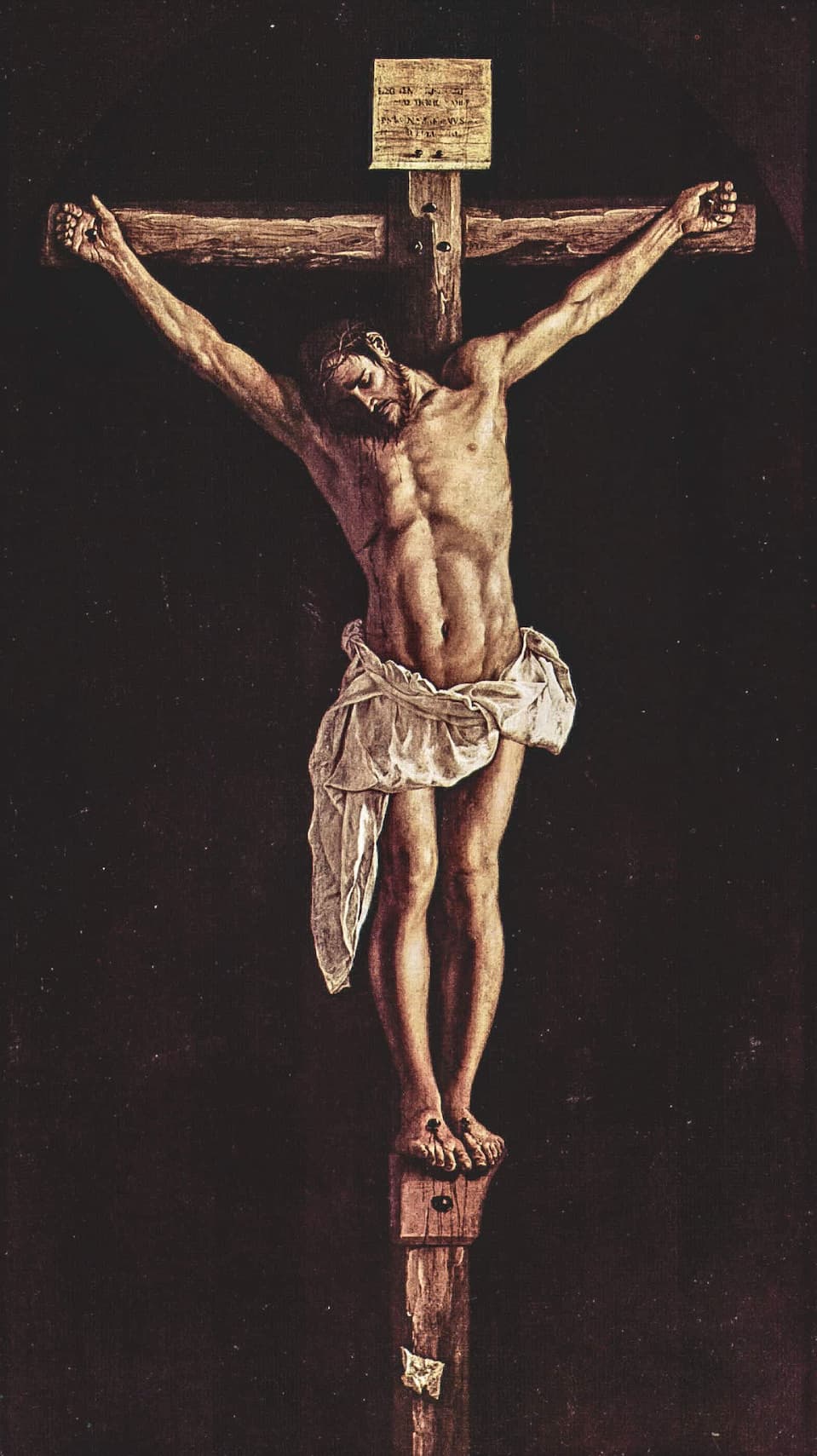

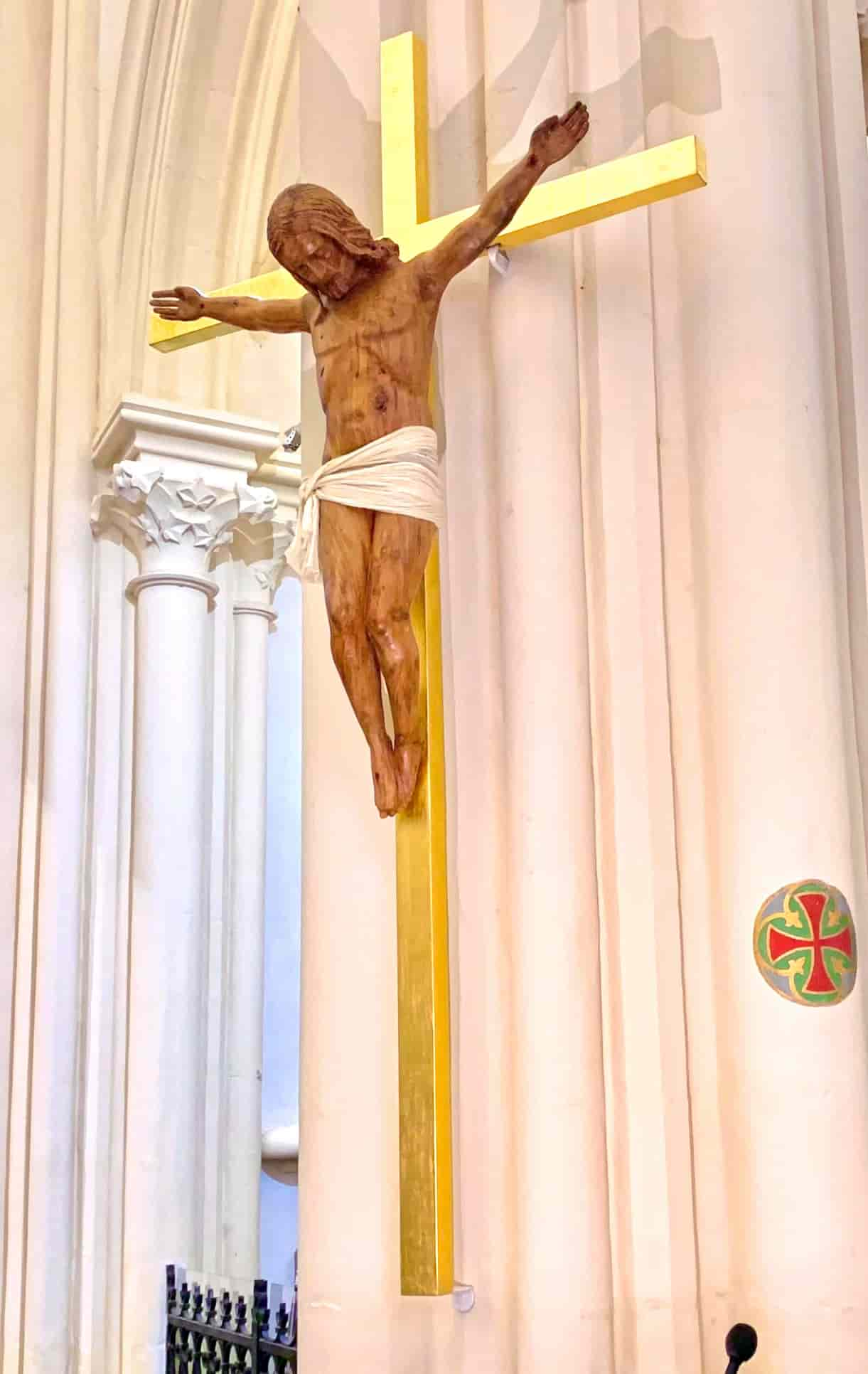

Perizoma in Art

The perizoma is only shown in a select few Christian icons. These are the paintings depicting Christ’s death on the cross, The Deposition from the Cross and the Pietà.

Other artworks include an ivory relief from c. 420–430, depicting the crucifixion of Christ in a perizoma; Perugino’s “Crucifixion” from around 1482, housed at the Washington National Gallery of Art; Francisco de Zurbarán’s “Crucifixion” created in 1627, which can be found at the Art Institute of Chicago; and Cornelis Schut’s “Deposition” from approximately 1630, currently displayed at Liège’s Grand Curtius museum.

References

- Glory of the Martyrs – Google Books

- Relics from the Crucifixion – Google Books