Are the Japanese Pagans or Buddhists?

Depending on whether you consider Shinto, the indigenous religion of Japan, to be a form of paganism, the issue of religion often baffles even the Japanese. A 2018 NHK survey found that 62% of Japanese people call themselves atheists. The other 31% are Buddhist, 3% are Shintoist, and 1% are Christian. Nonetheless, the majority of respondents (74%) believe that the Japanese islands are inhabited by “myriad gods” and make pilgrimages to Shinto shrines.

- Are the Japanese Pagans or Buddhists?

- Do they commit hara-kiri today?

- Is it true that Japanese women are not free and are submissive to their husbands?

- Who is Geisha?

- Do modern Japanese people wear kimonos?

- Why do the Japanese always bow down?

- Don’t the Japanese use chairs and beds?

- Do the Japanese drink only sake or do they also drink other alcohols?

- Do the Japanese eat sushi and rolls?

- Why do the Japanese go to see trees in bloom?

The “myriads of gods” include both local deities and national icons whose shrines may be found all across the country. The sculptures of foxes that serve as messengers for the deity Inari, who is in charge of success and wealth, make his temple most easy to locate. The most well-known Inari shrine is Kyoto’s Fushimi Inari Taisha. The scene in Rob Marshall’s Memoirs of a Geisha (2005), in which the film’s young heroine sprints through a tunnel of brilliant orange torii gates, contributed to Fushimi’s increased visibility. As the gateway to a holy site, they an act of worship to the gods.

Japanese people rush to Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples on the first few days of the new year to buy an amulet and get their yearly o-mikuji prediction. The ministers of shrines and temples put religious goshuin seals in special pilgrimage notebooks for a modest price, and collecting them has become trendy in recent years. Shinto shrines and Buddhist shrines (butsudan) are common fixtures in Japanese households (kamidan). Shinto and Buddhism cohabit peacefully, a phenomenon known as syncretism. Even though the majority of Japanese people are not Christians, a sizable number of them choose to celebrate Christmas and be married in Catholic churches. In a nutshell, Shinto deities Kami and Buddha, along with other religions, cohabit in Japan.

In the 6th century, the ruler of the ancient Korean kingdom of Baekje presented the Japanese king with Buddhist sutras and a statue of Shakyamuni Buddha, marking the beginning of the official history of Buddhism in Japan. For fear of angering the local kami, the old priesthood clans opposed Buddha worship. And when smallpox broke out, the statue of the “foreign deity” was dumped in the Naniwa Canal as a preventative measure. However, Buddhist doctrine quickly established itself in Japan, spawning several new schools of thought and becoming inextricably linked to Shinto.

If the new faith was so superior, then why didn’t it replace the old one? Because it was thought that gods, like people, were subject to the law of karma and suffered in an endless cycle of rebirths, Buddhist teaching was crucial in helping the kami deities achieve enlightenment. So, Buddhist sutras were recited to the Shinto deities in Shinto shrines. As a result, the deities gained status as the Buddhist guardians, and shrines to them were built on the premises of Buddhist places of worship.

Second, the rudimentary beliefs in the kami deities were developed into a sophisticated theory of the “way of the gods” under the influence of Buddhism and its intricate system of dogmas and rituals. Most notably, it detailed how the Buddha and bodhisattvas It detailed how the Buddha and Bodhisattvas, who were too lofty for commoners, took human form as Japanese deities to spread Buddhist law. There developed competing interpretations of Japanese mythology in the 15th and 16th centuries, suggesting that the Buddha and bodhisattvas were actually reincarnations of Japanese deities.

Finally, Buddhists handled funerals, protecting the kami deities from the grim reality of life’s final chapter. Ultimately, blood and death are the primary sources of kegare (Japanese for “bodily pollution”), and the Japanese gods will not accept it. This is why people are asked to wash their hands and spit in special stone bowls before entering a Shinto shrine.

The government chose to divide Shinto from Buddhism during the start of the Meiji period (1868–1922), when the cult of the emperor, a descendent of the sun goddess Amaterasu, who heads the Shinto pantheon, became the state doctrine. Shinto shrines that had acquired Buddhist temples, sculptures, and sutra scrolls were destroyed as part of an effort to “expel Buddha” from the domain of Shintoism.

Following the Japanese surrender in World War II, the Emperor renounced his position as “revealed deity” (arahitogami), Shinto was no longer recognized as the official religion of the country, and Buddhist preachers were called back into service. Currently, Shinto and Buddhism may live side by side without any problems.

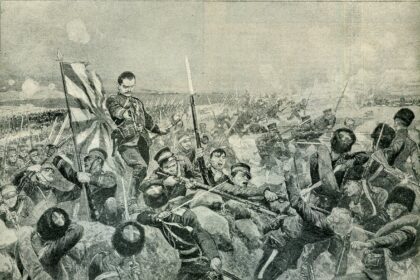

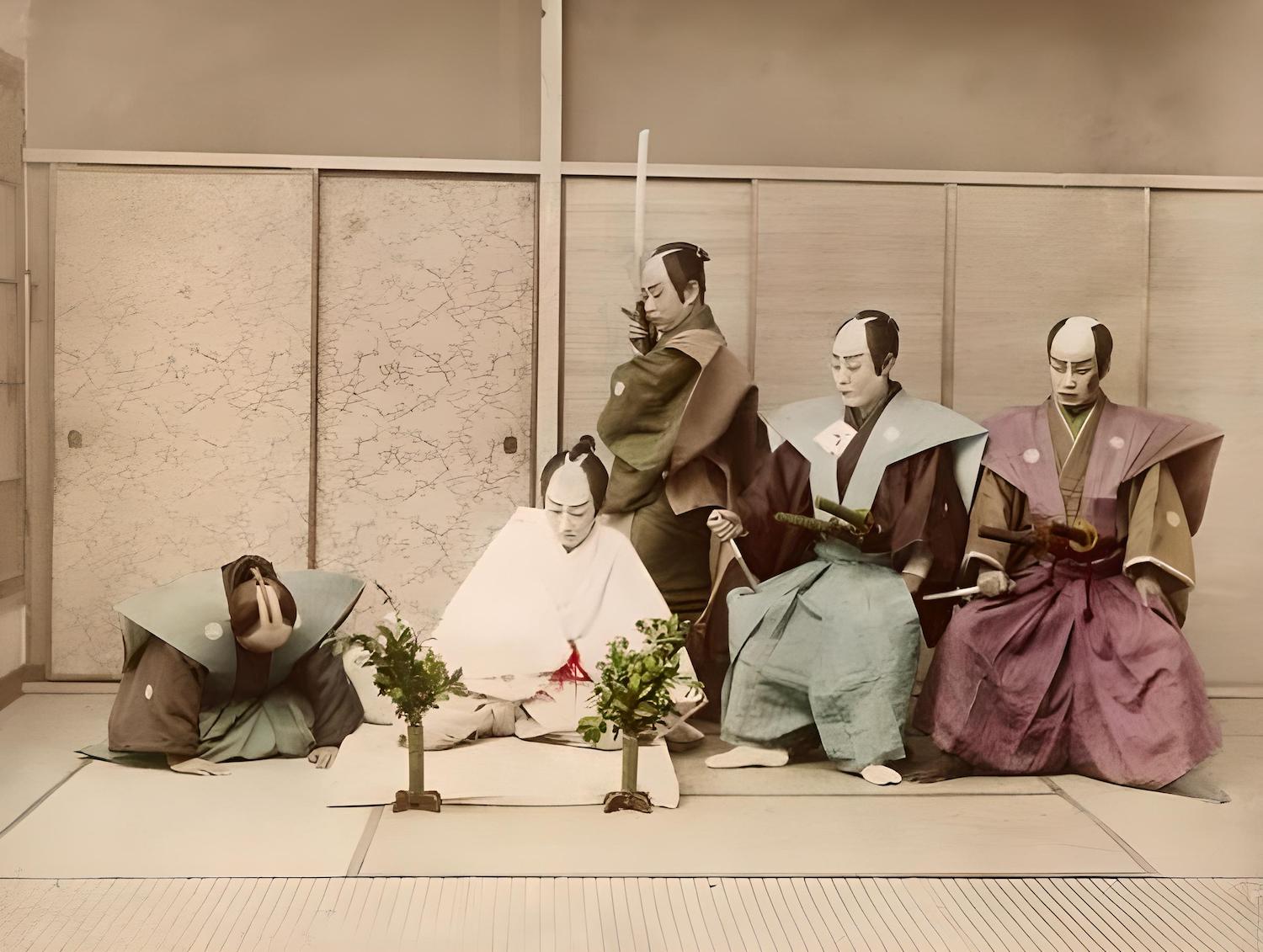

Do they commit hara-kiri today?

Suicide through harakiri (or seppuku in Japan) is a demanding ceremony that takes a lot of physical strength and energy. It is not done nowadays. The samurai have always been the only ones allowed to cut open their abdomens to prove their mental and spiritual purity. For example, a samurai would carefully tuck the sleeves of his waist-length garments behind his knees so that his body wouldn’t slide backwards during the ceremony, which was frowned upon during the Edo era. Death through seppuku is not instantaneous but rather a drawn-out ordeal. In order to complete what he began, namely, to cut off the head, a kaishiku assistant is required.

Author and samurai values advocate Yukio Mishima (1925–1970) was one of the last people to take his own life by cutting into his stomach (seppuku). On November 25, 1970, he and his fellow Shield Society members attempted to overthrow the government. When things didn’t work out, Mishima took his own life. But not very successfully; a helper botched the initial attempt to sever his skull.

Is it true that Japanese women are not free and are submissive to their husbands?

According to Olympic Games organizing committee director Yoshiro Mori in early February 2021, women take too much time thinking and are late to meetings. Even though Mori lost his job because of what he said, the comments were a stark reminder of the difference between men and women in Japanese culture.

In the World Economic Forum’s Gender Equality Index for 2021, Japan placed 120 out of 156 countries. For a country with a mature economy and a lot of women in school, the gap between men and women is shockingly big.

It was found in August 2018 that Tokyo Medical University has been intentionally underrating female applicants’ admission exam results for several years. That’s because, according to their explanation, many women choose to put their medical careers on hold while raising families. The result might be a scarcity of doctors, nurses, and other hospital workers. Women not only have fewer employment and career options but also typically receive a lower income than males in the same position, and this is not exclusive to the medical industry.

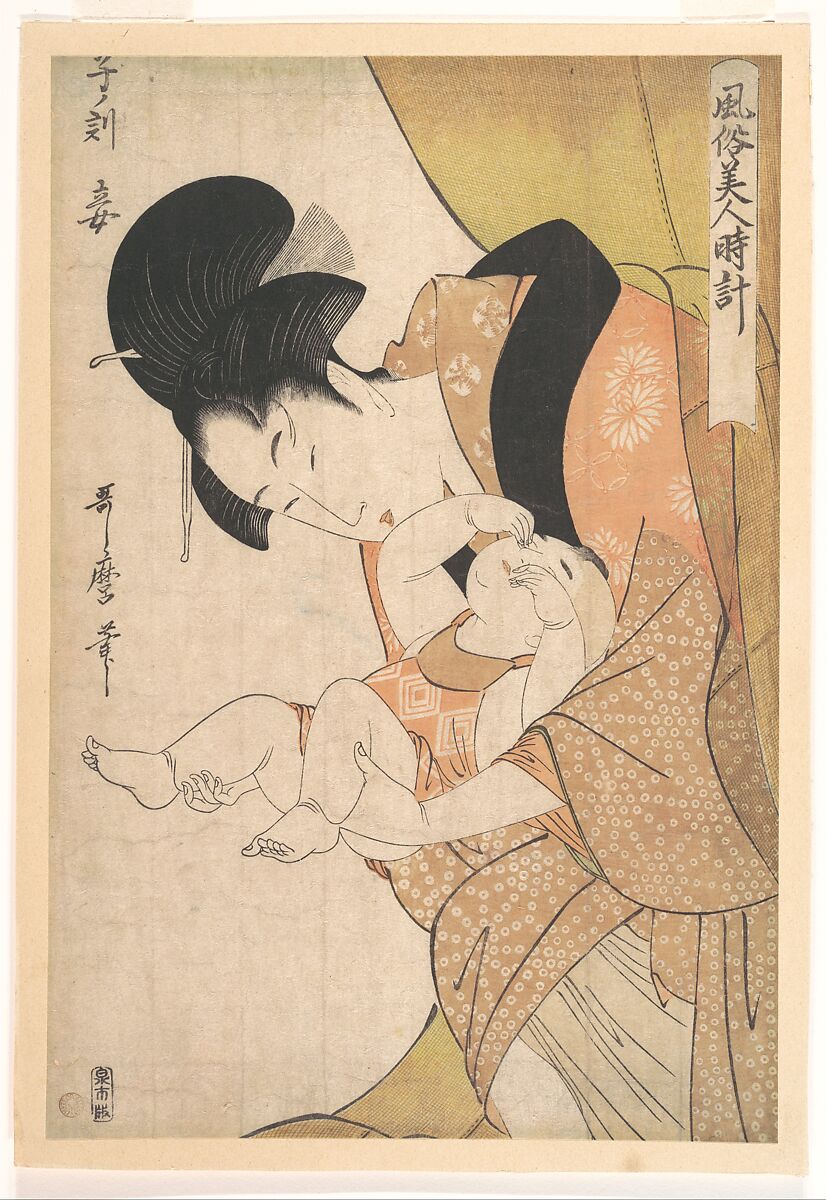

Do Japanese women who are married always stay away from work after giving birth? 82% of Japanese young women continue to work after marriage, and 57% of those women want to resume their careers after delivering a child, according to a 2020 Social Survey conducted by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. A separate study indicated that even though many women would want to stop working if their partners made more money, over half of those women still intended to do so. Women often hope that their spouses will pitch in with childcare duties. However, in practice, it is the woman who bears the brunt of responsibility for childcare and housework. As a result, this becomes the leading cause of women leaving the workforce.

Confucianism had a significant impact on how gender roles were divided in Japanese society. Although the Meiji reforms adopted Western liberal concepts and provided women with some rights, the ideal of the “Good Wife and Wise Mother” (ryosai kembo) remained the most important female virtue. One of the primary guides to the education of ladies up to World War II was The Great Learning for Women (“Onna Daigaku,” first published in 1716). It is commonly believed that the great Confucian scholar Kaibara Ekken (1630–1714) wrote this book. In this work, the Confucian scholar states that “a woman’s purpose is to serve people.” When she is living at home with her parents, she serves them; when she is married, she serves her husband and his parents. To be submissive and humble is the path of a lady. Additionally, the supreme deity of the Japanese pantheon, the “gracious sun goddess Amaterasu,” “woven her celestial robes.”

Patriarchal behaviors have not entirely vanished; women are still routinely discriminated against in the workplace and at home, even though Japanese women have the same rights as men and are not required to follow their husbands in everything.

Who is Geisha?

![10 Questions About Japanese Culture 5 Kotoba no hana [Flower of Words]. Yanagawa Shigenobu II (active circa 1830–60)](https://malevus.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2015_CSK_10430_0087_000yanagawa_shigenobu_ii_kotoba_no_hana_flower_of_words081124-transformed.jpeg)

A geisha, as opposed to a courtesan (yujo), is a “man of art.” The first geisha were mostly male actors who performed sexually explicit skits for the brothel patrons. By the middle of the 18th century, geisha had relocated from the pleasure districts to the flower districts (hanamati), and the geisha profession had emerged as a distinct occupation. Geishas were primarily responsible for entertaining visitors through the tea ceremony, chatting, singing, dancing, and playing the three-stringed samisen. Also, they were not allowed to profit from their bodies in any way.

Most people outside of Tokyo (formerly Edo) and the surrounding Kanto area don’t know what a “geisha” is. Their trainees are known as oshaku, or “pouring sake,” or as hanyoku, or “half-precious” (since their services cost half as much as a geisha’s). Geisha are known as geiko in the Kyoto-centric Kansai area, while their trainees are known as maiko (“dancers”).

Historically, girls from low-income backgrounds were offered employment in geisha houses (okiya); today, however, girls as young as 15 or 16 choose geisha work as a career path after graduating from high school. In the Hanamati, geisha and their trainees have their designated areas. Apprentices often train for two years before becoming maiko by giving their first public performance as dancers. She also gets a fancy new kimono and a custom-made tortoise comb from the geisha who trained her. Her new name is based in part on the name of her teacher (Kanzashi). The girl spends the last month leading up to her debut (misedashi) attending tea house banquets and learning from the other maiko and geiko there. Maiko gets compensated for signing up at a specific geisha office. Learning to be a geisha often takes between five and six years.

Maiko is easily distinguished from a geisha by her brighter ensembles and hairdos. The getta (platform sandals) are taller, the sleeve length of the kimono is longer, and the belt reaches nearly to the floor. In contrast to geishas, whose hair is usually a wig, students usually get their real hair done.

Geishas are becoming a dying breed as fewer and fewer young women choose to pursue the profession. In Kyoto, there are only 169 geiko and 68 maiko who are officially recognized.

Do modern Japanese people wear kimonos?

Geishas, noh performers, and kabuki actors all wear kimonos to work. The kimono is also traditionally worn at formal events like weddings, funerals, college commencements, and other such ceremonies. Kimonos are also commonly worn at formal events, including weddings, funerals, college commencements, and other ceremonies. Girls should wear the furisode, a colorful long-sleeved kimono, at their coming-of-age ceremony since it is customary to do so before marriage.

About 80% of Japanese women and 40% of men have tried on a kimono at some point in their lives. However, this traditional attire is costly, so most people only wear it on rare occasions or opt to rent it. Putting on a kimono correctly may be challenging, so much so that classes are offered to teach the proper way to do it. The yukata is yet another example. During summer festivals, women wear this style of kimono because of its lighter fabric. Yukatas are traditional bathrobes used by guests at hot springs and hotels.

Taking a stroll around Kyoto’s historic alleyways while dressed in a kimono or yukata has grown increasingly popular among both sexes in recent years.

Why do the Japanese always bow down?

The act of bowing is not only essential to social interaction in Japan and East Asia but also serves as a valuable social marker that helps us gauge a person’s status and select an acceptable behavioral template. One common example is that the younger or lower-status person will bow first in a social situation. His bow will always be slightly lower.

In daily life, a bow can stand in for a variety of spoken expressions, including a request, a thank you, or an apology. A short, high nod means you’re glad to see someone, while a long, low nod means you’re sorry.

In the 12th century, the military elite refined the bowing ceremony into its present form. There were specialized academies for teaching this skill, as well as archery and horseback riding. One of the most well-known is the Ogasawara family’s etiquette academy. Business etiquette is still taught by the modern-day offspring of that ancient samurai family.

Since the bow always indicates social hierarchy, the handshake’s lack of popularity in Japan can be attributed to the fact that it represents equality. As long as traditional forms of power and government control are kept in place in Japan, the bow will continue to be used.

Don’t the Japanese use chairs and beds?

In Japan, chairs and beds are more like accessories than necessities. European-style furniture, including chairs and beds, began appearing in many aristocratic homes in the early Meiji era. Even though most modern Japanese homes are furnished in the European style, some still maintain rooms decorated in the traditional Japanese manner, complete with tatami mats and a tokonoma alcove adorned with ikebana and a scroll of paintings or calligraphy.

In contrast to detached homes, studio apartments have such little square footage that a standard bed won’t fit. A futon may be used as a mattress at night and folded up and stored during the day. The poll found that just 40% of Japanese respondents were interested in sleeping on a futon, while 60% preferred a bed or standard mattress. It is common to use a low table and zabuton cushions instead of a high table and chairs (sometimes with a wooden back). The kotatsu is a low table used in the wintertime that has a blanket draped over an electric (or less commonly, a charcoal) heating source and a tabletop put on top of it.

The traditional Japanese concept of space does not imply cumbersome and bulky objects. Wabi-sabi emphasizes refined minimalism and a sense of wholeness in a home, so extraneous pieces of furniture are out of place. To quote the great Tanizaki Junichiro, “When Europeans view a Japanese home space, they are stunned by its artless simplicity,” from his classic “Praise of the Shadow.” They find it peculiar because all they can see inside are blank gray walls.

Do the Japanese drink only sake or do they also drink other alcohols?

There is no alcoholic beverage more well-known in Japan than sake. Among Japanese people, it is known as nihonshu or washiu, while “isake” is a generic term for alcohol. Since sake is manufactured by pasteurization rather than distillation, the common translation of “rice vodka” is inaccurate. Sake, like wine, is produced by fermentation, specifically mold fermentation; however, in this case, the mold is naturally occurring. Originally made as an offering to the gods at Shinto temples, at the Tokyo shrine gate of Meiji Jingu, you may view rice wine gifts in the form of barrels braided with straw rope.

In addition to sake, the Japanese also consume shoyu, a stronger liquor distilled from rice, rye, and sweet potatoes (with an alcohol content of 20–25 degrees). Most of it comes from Kyushu, Japan. Awamori, distilled from raw rice, has an alcohol content of 30 to 60 degrees and is produced on Okinawa, a southern Japanese island.

In contrast, beer is a popular drink among Japanese people. It’s far superior to wine and umeshu plum liqueur. Whiskey is the drink of choice for those who appreciate superior beverages. It is estimated that Japan produces 5% of the world’s total supply of this beverage. As an illustration, Suntory’s 17-year-old whiskey, promoted by Bill Murray’s character in “Lost in Translation,” became so famous that the business ceased making it due to overwhelming demand.

Do the Japanese eat sushi and rolls?

Nigiri-zushi is the most common sushi style in Japan, while the Japanese more commonly refer to sushi as sashimi (a piece of fresh fish on a ball of cooked rice). Until the 19th century, sushi fish was fermented rather than uncooked.

Both high-end sushi restaurants, where the customer often leaves the decision up to the chef (with phrases like “At your discretion” or “Omakase”), and low-end sushi kaiten-zushi restaurants, where customers select their sushi from plates on a moving conveyor belt, serve the Japanese delicacy. The supermarket sells sushi kits, and customers eagerly await the nightly price decrease and the arrival of the desired sticker proclaiming the discount. Even though sushi might be pricey, it’s still more like quick food than fine dining.

Why do the Japanese go to see trees in bloom?

This custom goes back centuries. During the Heian period (794–1185), the plum gave way to the decorative cherry, the sakura, a habit that had been imported from China in the 8th century. While there are 110 poems about plum trees in the 8th century’s “A Collection of Myriads of Leaves” (“Manyoshu”) but only 43 about cherries, there are 70 songs about cherries but only 18 about plums in the early 10th century’s “Collection of Old and New Songs of Japan” (“Kokinwakashu”). The simultaneous blooming of cherry trees inspired the term “hanami” (meaning “flower appreciation”).

According to legend, King Saga ordered the first hanami celebration to be staged in 812 at the Shinsen-en garden of the Kyoto Imperial Palace to celebrate the blossoming of a cherry tree. The aristocracy’s appreciation for the sakura’s ephemeral beauty stems from the Buddhist concept of the impermanence of all things and the aesthetic category of mono no aware, “the melancholy attraction of things” in a constantly shifting world.

As early as the 8th century, the Japanese noticed that epidemics often broke out in the spring when the cherry blossoms were ending. Because of this, a myth developed suggesting that the waning flowers’ disembodied spirits were to blame for the epidemic. Due to this, ceremonies called “flower soothing” (tinkasai) were performed by the Imperial Court’s Office of Temples and Sanctuaries (Jinggikan). A visit to Imamiya Shrine in northern Kyoto on the second Sunday of April will allow you to witness this rite as it is practiced now.

For the affluent, the transient beauty and ephemeral nature of life reflected in the cherry blossoms were a sobering reminder, while for the common folk, the flowering trees had a more celebratory significance. They thought that the gods of plenty would come down from the hills to the rice paddies in the spring. They made their temporary home in the sakura (from the words sa, meaning “deity of fertility,” and kura, meaning “dwelling place”). The gods were welcomed with offerings of food and music left at the base of flowering trees. As long as the sakura were in bloom, the god would stay, which would lead to a good harvest.

During the Edo era, cherry picking was practiced by people from all walks of life (1603–1867). To share his enthusiasm for cherry blossoms with the people of Edo, the monk Tenkai (1536–1643) transplanted trees from Mount Yoshino (Nara Prefecture) to the grounds of Kan’eiji Temple in Ueno Park. During cherry blossom season, the shrine quickly became a popular gathering spot for locals. The monks at the monastery where raucous cherry blossom walks were held complained to Shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune in 1720, prompting the Shogun to order cherry trees to be planted across Edo to inspire widespread celebration. Ueno Park in Tokyo is one of the most popular urban parks in Japan and was recommended as one of a hundred great places to see cherry blossoms in 1990 by the Japanese Cherry Blossom Association.