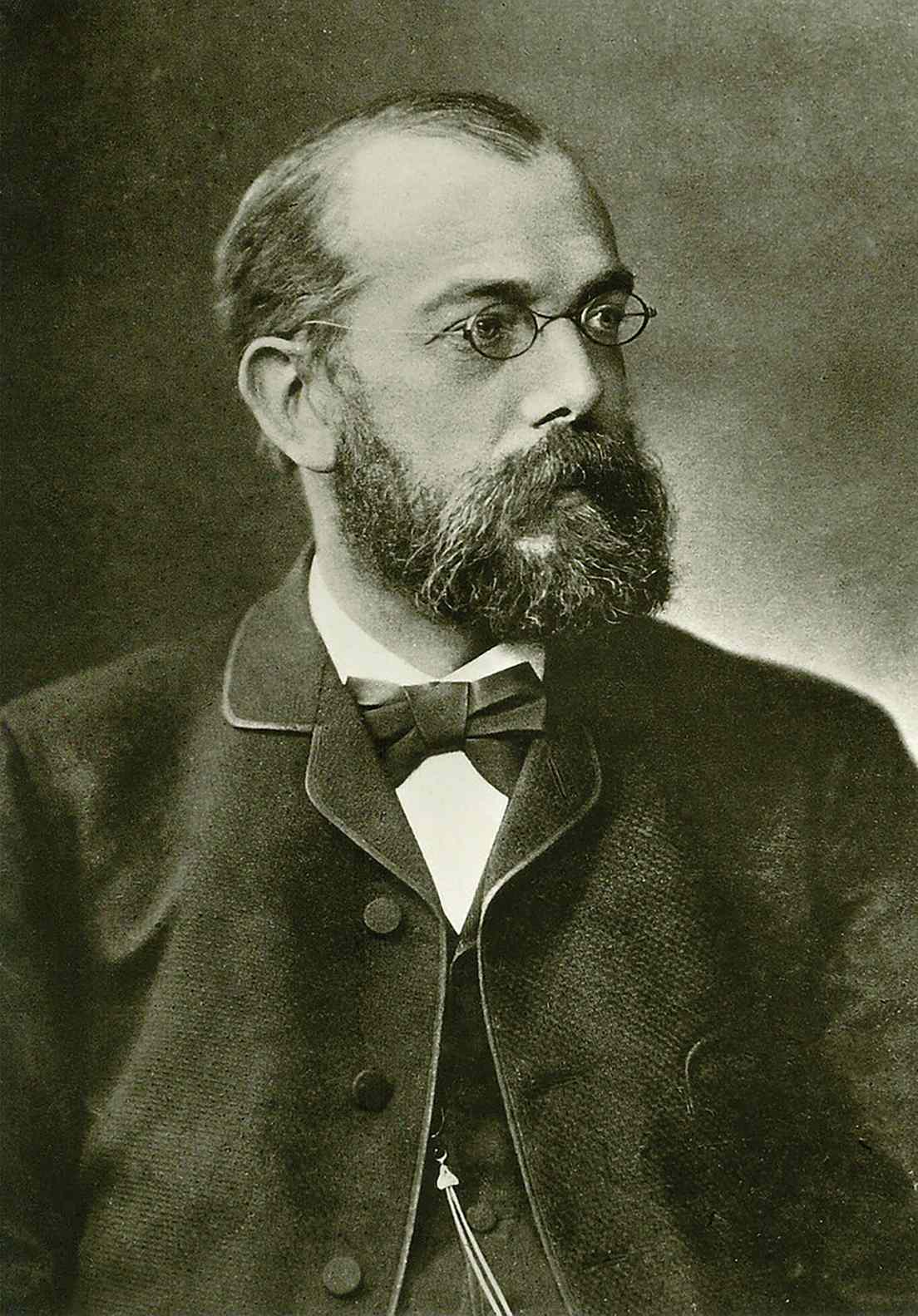

Nobel Prize recipient Robert Koch (1843-1910) is well recognized as a groundbreaking figure in the fields of bacteriology and infectious medicine due to his discoveries of the tubercle bacillus and the anthrax pathogen. The great Alexander von Humboldt served as an inspiration for him to pursue a career in exploration and travel. Robert Koch, on the other hand, did not make his groundbreaking findings in some remote location but rather in the human body itself.

An unheralded country doctor made a significant contribution to medical knowledge at a time when physicians were powerless in the face of terrible infectious illnesses and still believed that “polluted air” was the source of many dangerous outbreaks. Anthrax, TB, and cholera were three of humanity’s worst enemies at the time, but once Koch discovered that they were caused by bacteria, the war against them became a resounding victory.

Koch’s studies are as readable as the first few entries in a medical dictionary. He was successful in isolating the microbes responsible for a wide range of diseases, including anthrax, babesiosis, and cholera. Koch, however, accomplished far more than that. His methodical approach allowed him to devise methods for fending against microorganisms. By doing so, he established the cornerstone of modern sanitation.

Koch, though, never gave up on his dream of seeing the globe. So he didn’t think twice about pursuing both his career and his passion by jumping at every chance to investigate epidemics firsthand. He often visited the world’s most inaccessible regions while transportation was still difficult.

The start of an adventurous career

From a coal miner’s kid to a medical doctor

At the age of five, Robert Koch surprised his parents in 1848 by revealing that he had taught himself to read with the aid of a newspaper. Born in Clausthal, in the Harz Mountains, in 1843, the third son of a miner’s family, this accomplishment immediately offers a sense of the boy’s degree of intellect and methodical persistence.

Before beginning his studies in natural sciences at the University of Göttingen in 1862, he had planned on becoming a global traveler. But he quickly realized that was not what interested him, so he went into medicine instead.

It all started with animal feces

Here he encounters Jacob Henle, an anatomy professor who in 1840 presented the hypothesis, widely regarded as fantastic at the time, that infectious illnesses were caused by live parasitic organisms. Henle, a microscopy expert at the time, utilized the method to find germs in the feces of sick animals. However, he failed to present evidence connecting the parasites to the illness. However, Koch was fascinated by Henle’s research.

As a student, he lives by the mantra “never idle,” and as a result, he completes his PhD work well in advance of taking the required state examinations. When Koch finishes his PhD in chemistry, he spends six months in Berlin, where he is heavily influenced by Rudolf Virchow.

Hamburg in lieu of the rest of the world

After passing the state test in 1866, Koch wanted to work as a ship’s doctor or in the military. He was unable to pursue this goal, however, due to a combination of limited opportunities and his fiancee, Emmy Fraatz’s, strong aversion to international travel.

Instead, he began his career as a medical assistant in Hamburg. For the first time, Koch sees firsthand how terrible a cholera pandemic can be. His curiosity is piqued when he examines pathological specimens under the microscope.

Medical service in the military

Before then, however, he worked as a physician in the rural communities of Langenhagen, Niemegk (Brandenburg), and Rackwitz (near Posen). When the Franco-Prussian War broke out in 1870–71, Koch was finally able to leave his domestic idyll and follow his lifelong ambition of becoming a military doctor. He reported right away as a volunteer physician at the field hospital, despite the fact that he had extreme myopia. He was able to obtain invaluable expertise here in diagnosing and treating typhoid and wounds, which he would later use in his medical practice.

After the war, Koch finished medical school and began working as a medical officer in the little village of Wollstein, close to Posen, where he also opened his own medical practice. As both a doctor and an obstetrician, he served the community in this role. But his routine at the office wasn’t satisfying him…

From town doctor to an established academic

Searching for anthrax

Anthrax wiped out Europe’s cattle population year after year. When Robert Koch was a rural doctor in Posen, he too was faced with the catastrophic effects of this illness. His patients were constantly complaining about how the illness had destroyed their ability to make a living. Several instances occurred even on fields that had been dormant for a long time.

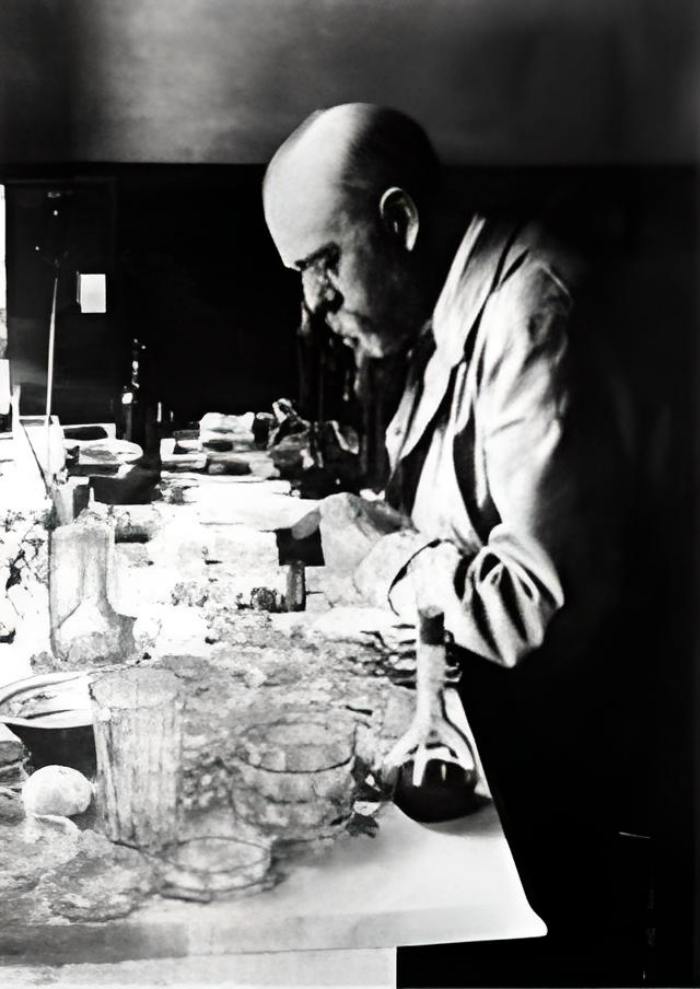

In light of this, he decided to investigate the matter further. Koch, isolated from the scientific community and distant from libraries, undertook independent research in his leisure time with only rudimentary resources. Starting off, he used one of the four bedrooms in the apartment where he lived with his wife and newborn daughter as a makeshift laboratory.

But what was Koch’s safety net, exactly? In his day, what information was available concerning anthrax? He didn’t have to relearn anything from scratch because of his old professor, Jakob Henle. In the 1940s, Henle hypothesized that a live creature, the so-called “Contagium animatum,” was responsible for spreading the illness. In 1849 and 1863, scientists discovered the anthrax bacteria (Bacillus anthracis), but they did not make the link between the organism and the deadly illness until much later.

Cow blood for clues

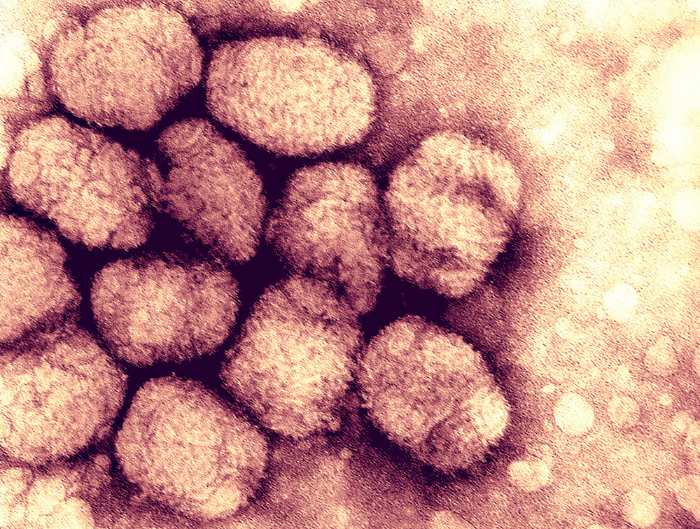

Since this was not a mystery to Koch, he could now effectively search for it. He then spent a ton of money on a microscope and started looking at the tissues and blood of animals that had perished from anthrax. When doing so, he came across millions of rod-shaped anthrax bacilli.

But can we be sure that their presence was due to the sickness, or was it just a coincidence? This was the point at which Koch really started doing research. Mice and guinea pigs were injected with blood from recently murdered cows, and he watched the results with bated breath. As expected, the animals’ spleens quickly developed a yellow tint and enlarged. They died a few times after that. Koch investigated the dead animals and discovered infections in all of them. His findings confirmed what had previously been observed: the blood may contain anthrax.

Pathogen identified

Koch, however, was not satisfied with this. He needed evidence that the germs in the blood were responsible for the illness, rather than some other factor. He required bacteria that had never been exposed to diseased animals or their blood to do this. So he began cultivating sterile bacterial cultures and searching for an appropriate medium. The nutrients he needed were most concentrated in the chamber water of ox eyes, he discovered. He raised many generations of the bacterium in his lab. By infecting animals in the lab, he demonstrated that the offspring germs were really virulent enough to cause anthrax.

What’s up with those spores?

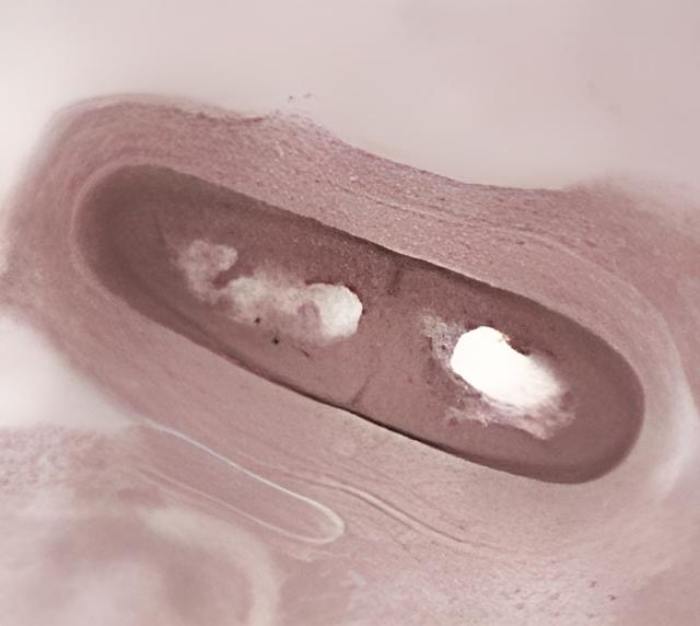

Koch, using long-term microscopy, discovered that the bacteria not only thrived in adverse circumstances such as a lack of oxygen but also produced spherical, resistant permanent forms that could germinate into new anthrax bacilli even after years of hibernation.

It was now understood why sporadic outbreaks of anthrax occurred in long-abandoned pastures. The pathogen’s spores leaked from deceased animals into the soil, where they persisted for years before being re-transmitted to grazing animals. Koch, therefore, identified the root cause of the catastrophic losses of animals that had been occurring frequently.

When the subject of bacteriology was still in its infancy, Koch went to Breslau in 1876 to submit his results to botanist Ferdinand Cohn. He made a big splash and got a lot of attention. Louis Pasteur, building on Koch’s research, created an anthrax vaccine in 1881.

An emerging field: Bacteriology

Koch spent the years after the publication of his findings on anthrax in 1876 honing his microscopic skills. He created new techniques for staining and took the first images taken with a microscope. Because of this, he had a resource for spreading the word about his findings to the general population. He was quite optimistic about this new method, saying, “You can show a photograph around as evidence among colleagues, you can reproduce it in a publication, and besides, the photographic plate is more sensitive than the retina of the human eye.”

He established the basis for contemporary bacteriology with his methodical methodology, microscopic detection, pure culture growth, and transfer to experimental animals. It was a step toward understanding other infectious illnesses as well.

The unexplained tragedy of surgical fatalities

After discovering the anthrax bacillus, Koch believed that each wound infection was caused by a distinct pathogen. Consequently, he dove headfirst into his study. The publication of his discoveries in “Etiology of Wound Infectious Diseases” in 1878 elevated his status in the scientific community.

Not long after, the brand-new Imperial Health Department saw him and invited him to Berlin. In 1880, Koch became the director of the bacteriology department at the university. There, he had access to both personnel and cutting-edge laboratory technology, allowing him to advance his study beyond what was feasible in his hometown.

But soon he found himself preoccupied with a new issue: the persistent occurrence of mysterious fatalities after surgical operations in hospitals. Patients are dying in droves from infections, despite the fact that the procedures themselves pose little risk of death. The riddle was solved by Robert Koch’s enhanced staining procedures. This allowed him to find bacteria in places where they were most unwelcome, such as on the surgical equipment used by physicians in hospitals.

Carbolic acid-resistant infections

Because of this insight, he began studying infectious diseases and creating specific cleanliness practices. Through a battery of tests, he demonstrated that the then-standard disinfectant, carbolic acid, killed bacteria at a concentration of 2% but had no impact on spores. Koch discovered that this was true only at a 5% dilution.

Nonetheless, this only held true if the carbolic acid had more time to have its effect on the spores. In reality, only a light sprinkle or spray was used to disinfect items. Koch understood that this approach to disinfection was very risky. Noting that “it is not sufficient to eradicate the living forms of the bacteria,” he stressed the need for “rendering harmless the spores, which are far more resistant.”

Fumes of heat

Koch set out to discover other approaches that would ensure effective sterilization. Sterilization using heat was used by several hospitals. Koch was able to utilize one of these massive germaphobe machines at the Moabit Municipal Hospital. His experiments indicated that heat alone had almost no impact on the spores, and this was true in both cases. Koch tried many approaches before settling on one that worked for him. He settled on utilizing superheated steam, which proved to be far more successful in terms of sterilization.

By 1881, his findings had been published in a seminal work that had become the standard reference for the field of bacteriology.

Koch’s postulates

A checklist for pathogens

Koch was able to differentiate between bacterial strains because of his staining methods. Now he had to start the laborious process of linking particular germs to their corresponding illnesses. He reasoned that every illness must have a unique pathogen. He was optimistic that the sickness might be brought under control once the causative agent had been identified. Koch was approaching the problem in a methodical manner.

To begin, he verified that the infected host had a pathogen at all times. After removing the germs from the infected host, Koch cultivated them in vitro. Then, he used these cultures to inoculate animals in the lab and watch for any signs of illness. If so, he did the second round of pathogen isolation and microscopic comparison. If they were the same, then he knew for sure that this particular bacterium was responsible for the illness.

Checking for pathogens

At the 10th International Medical Congress held in Berlin in 1890, Koch gave a speech on bacteriological research and outlined the criteria a pathogen must meet in order to be deemed unequivocally the cause of an illness:

- First, it must be shown that the parasite is present in each and every instance of the disease in issue, and that it does so under environmental settings that mirror the pathological alterations and the clinical progression of the illness.

- Second, it is not an accidental, non-pathogenic parasite in any other illness;

- Thirdly, that it can re-breed the illness in pure cultures a sufficient number of times without ever coming into contact with a human host.

According to Koch, it would thus be impossible for the sickness to have occurred by chance, and it would be impossible to conceive of any other connection between the parasite and the disease other than that the parasite was the cause of the disease.

Friedrich Loeffler, one of Koch’s coworkers, popularized the term “Koch’s postulates” to refer to this set of principles, which remain relevant today in a somewhat modified form. However, they no longer apply without qualification in the same way that they did during Koch’s lifetime. He had previously hit a dead end in his study of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae because he couldn’t get the isolated bacterium to infect experimental animals.

Meanwhile, pathogens have been found that do not meet all the criteria. One cannot simply cultivate viruses in a medium of their own kind. Like many other infections, Neisseria gonorrhoeae affects animals but not humans. Only with the help of cutting-edge molecular biology techniques is the HIV virus detectable. Therefore, a fourth postulate was added to the set, detailing the identification of immunological pathogen-host connections.

Koch’s postulates centered on whether or not a certain pathogen was responsible for a given sickness. On the other hand, the updated version was used to find the illness’ cause when dealing with known diseases.

The discovery of the tuberculosis pathogen

In the middle of the nineteenth century, TB was one of the leading causes of mortality in Europe, prompting headlines like “Europe in the death grip of tuberculosis!” in Berlin newspapers. About one-seventh of the population was affected by this pandemic throughout the nation.

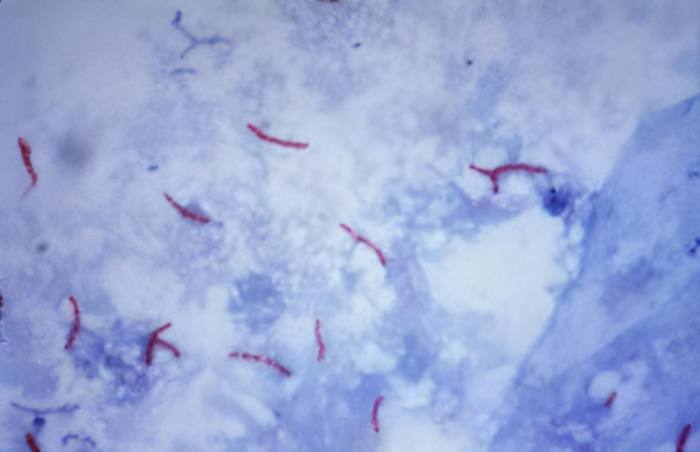

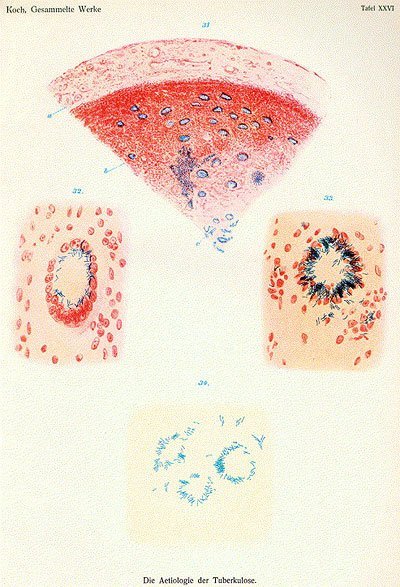

Robert Koch had the same difficulties as any other doctor in this situation. He and his staff dove headfirst into studying this “scourge of humanity” in 1881. Using human lung tissue taken after death, he injected rabbits and guinea pigs with tuberculous bacteria. Simultaneously, he looked at the tissue under a microscope but was unable to discover any germs at first.

Eventually, after painstakingly testing several staining processes, he was able to recognize the small, rod-shaped formations. Meanwhile, Koch’s afflicted test animals also began to perish. Under the microscope, he discovered identical rod-shaped germs in all of the dead animals.

A goal, rather than a partner

However, culturing the bacteria in a sterile environment proved challenging. After 15 days, he saw that microscopic colonies were only forming after he added blood serum to regular agar (in a Petri dish) as an extra food source. He knew he had found the TB-causing agent when he was able to infect laboratory animals with the daughter microbes.

In his lecture titled “Etiology of Tuberculosis,” given on March 24, 1882, Koch informed experts that the bacilli found in “tuberculous substances are not merely the companions of the tuberculous process, but the cause of it.” To back up his claim, Koch showed photographs of microscopic tissue preparations in which he had visualized the rod-shaped bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis by means of a color reaction.

This was the pinnacle of his scientific career. In the end, Koch became one of the Imperial Privy Councilors. In 1885, he became the first head of the Institute of Hygiene at Berlin’s University of Berlin and was promoted to the position of professor.

To find an antidote

Koch, who had previously focused on education, shifted his focus to finding a treatment for TB. He learned how to make a vaccine by reading the work of Louis Pasteur, one of his competitors. He injected guinea pigs with a serum made from TB germs that he had previously killed in his lab’s centrifuge.

He injected the animals with live TB germs and observed them closely. Koch considered the localized reddening of the skin that occurred after immunization to be protective against a subsequent illness. In the end, he came to the conclusion that this vaccine made it possible to not only identify an illness but also treat it while it was still in its earliest stages.

His “Tuberculin” was met with great applause when he introduced it at the 1890 Berlin International Medical Congress. He just hinted at its contents, though. A compound he had discovered “is capable of halting the development of tubercle bacilli not only in the test tube, but also in the animal body, such that guinea pigs, when exposed to such a material, no longer respond to inoculation with the tuberculous virus,” he said.

From the highest of highs to the lowest of lows

Patients went in droves to Berlin’s specially constructed sanatoriums in order to get treatment with the wonder medicine. But soon there would be hearses parked outside since the vaccination wasn’t working. It seemed to exacerbate TB rather than alleviate it.

Rudolf Virchow, a pathologist who was initially skeptical of Koch’s findings, conducted an autopsy and found tubercle bacilli in the corpses of the dead. It was now time for Koch to confess that tubercle bacilli were the active ingredient in his miraculous therapy. There was a lot of outrage at the news once it was announced. Koch was forced to face a crushing loss and widespread condemnation.

After Clemens von Pirquet’s research established the use of tuberculin in diagnostics, his name was finally rehabilitated. Von Pirquet explained that a red rash caused by an allergic reaction was a sure sign that tuberculosis germs were already present in the body. Today, patients who have been diagnosed with TB still get tuberculin injections under the skin with a four-pronged needle. When pustules appear at the injection site between 48 and 72 hours later, the test is deemed positive.

The development of the diagnostic test, although a boon, did nothing to ease Koch’s suffering. He felt guilty about a lot of different individuals. After decades of study, Koch was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology in 1905 for his contributions to the science of TB.

On the trail of cholera

Egypt and India as places to look for disease

Fevers, nausea, diarrhea, and ultimately death. The emergence of these symptoms was rarely a lone occurrence. Cholera had been a recurring problem in Europe since 1817, and it had claimed many lives. In 1883, when another pandemic erupted in Egypt, they worried it might spread over the continent.

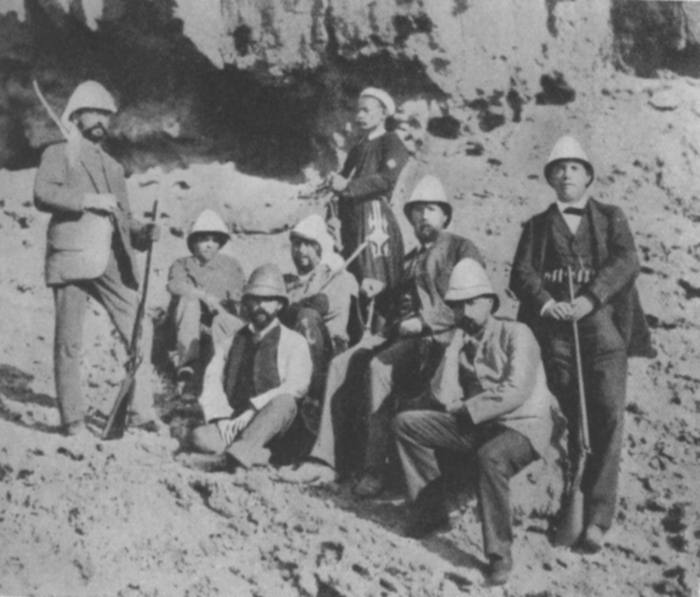

It was the perfect chance for Robert Koch to fulfill his wanderlust. In order to investigate the sickness firsthand, he joined a government delegation from Germany and went to Alexandria. Basically, he uncovered the causative agents of amoebic dysentery, rinderpest, bubonic plague, sleeping sickness, and bacterial conjunctivitis.

Is the “comma” a cholera virus?

Cholera, however, was his primary concern. Soon, he began to assume that a certain comma-shaped bacteria was to blame for the outbreak. Unfortunately, he was unable to finish his study before the conclusion of the pandemic in Egypt. Feeling somewhat defeated, he returned to Germany with pure cultures of the suspicious infection.

From this location, Koch learned about a new cholera epidemic in India and set sail for Calcutta at once. In several cases, he also discovered comma-shaped bacteria in the patients. Even though he was unable to inoculate animals with the bacterium, he was certain that Vibrio cholerae was the cause of cholera.

But it wasn’t good enough for him. In order to effectively combat the sickness, he was concerned about its transmission. It took him a while, but he eventually tracked the bacteria to tainted water storage containers and learned that they spread by ingesting contaminated food or wearing infected textiles.

“I forget that I’m in Europe”

When Koch returned to Berlin, he quickly instituted a system of routine water quality monitoring and suggested a number of sanitation-related enhancements, including the installation of water filters. He established a framework for future efforts to control epidemics.

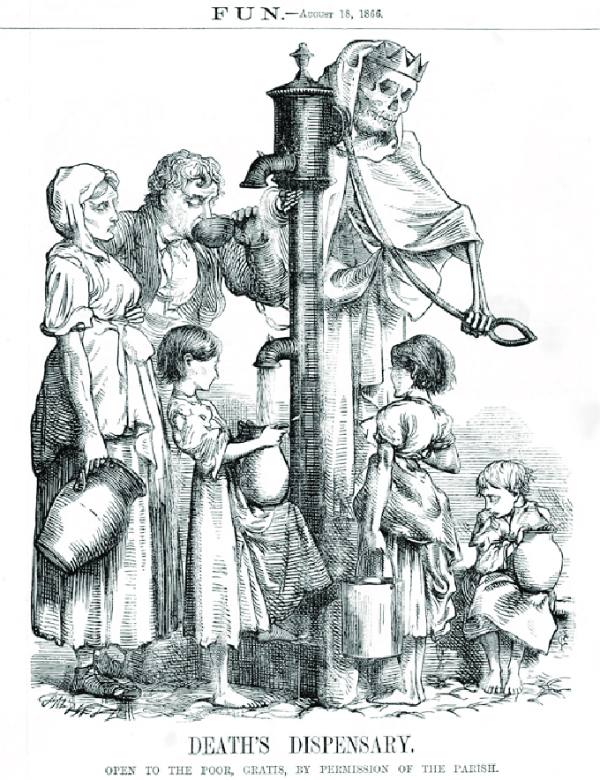

The Prussian government sent Koch to the site of the 1892 cholera epidemic in Hamburg so that he might advise the Hamburg Senate. When he got there, he saw the squalor and filth that had settled into the impoverished areas and the emigrant barracks, and he was horrified. He blasted the Senate and demanded immediate action, saying things like “Gentlemen, I forget that I am in Europe.”

During his lifetime, Koch was heralded as the one who discovered the cholera pathogen, however, the actual discovery really predates his. In 1854, the bacterium was first isolated by the Italian anatomist Filippo Pacini. Miasma theory, which held that contaminated air was the root cause of many ailments, was still popular at the time, therefore his study was ignored.

Koch also discovered the finding independently of Pacini, who was ignorant of his colleague’s efforts. This time, the discovery was not lost to the benefit of humanity because of his popularity and celebrity. It was not until 1965, however, that the bacterium was formally named Vibrio cholerae Pacini 1854.

Robert Koch as head of the later Robert Koch Institute

Bacteriology has flourished ever since Koch’s seminal discovery. The major focus of scientific investigation has always been finding ways to either stop the spread of infectious illnesses or slow the pace of epidemics. In 1885, Robert Koch was hired as the head of the Institute of Hygiene at Berlin’s Friedrich-Wilhelms University. Many medical professionals with an interest in bacteriology flocked to Berlin because of his fame. Over time, the prerequisites became inadequate.

“Robert Koch Institute” is founded

The Royal Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases, which was the first version of what is now the Robert Koch Institute, was set up next to the Charité in 1891, and Koch was named its director.

This is where abilities like those of Paul Ehrlich and Emil Adolf Behring, later recipients of the Nobel Prize in medicine, who made significant strides against diphtheria and syphilis, come into play.

The institution, which was first located in a residential building, was merely a temporary solution, since construction on a new structure that was specifically designed to meet the demands of the scientists had already started.

The building was finished in the summer of 1900 at its current site in Berlin-Wedding, with stables and housing for the cattle, horses, sheep, and frogs reared as experimental animals.

Travelers with an insatiable curiosity

Koch, however, was not content with the monotony of his home laboratory. His curiosity and sense of adventure inspired him to make many trips to the affected areas so that he could investigate the causes and spread of the sickness firsthand. In between these expeditions, he would travel to Europe and the United States to present the findings of his study at international conferences.

He had been devoting his life to the study of tropical illnesses since 1896. Rinderpest, Texas fever, and coastal fever were just a few of the animal illnesses that were a problem in southern Africa. He was unable to pinpoint the specific agent that causes rinderpest, but his efforts to inoculate healthy cattle with bile from sick animals halted the disease’s progression.

The race in malaria research

However, human-transmitted illnesses such as malaria and sleeping sickness pique his attention. Prussian authorities, upon learning of his return to Germany, sent him to Italy and the tropics to probe the source of a malaria pandemic. Very quickly, he learned that there were really four distinct types of malaria. Unfortunately, the exact mechanism by which the illness spread remained unknown.

The Anopheles mosquito was Koch’s prime candidate, but Ronald Ross of the United Kingdom beat him to the punch by publishing a detailed account of the parasite’s life cycle in Anopheles mosquitoes. Koch’s studies back up these claims. He had been using quinine, an extract from cinchona bark that was effective against the disease’s asexual phase, to effectively manage the outbreak.

He still fought epidemics in retirement

His last years

At age 60, Koch stepped down as head of the Institute of Infectious Diseases in 1904. But not to relax, but to devote all of his energy to his future adventures.

That same year, he returned to East Africa to investigate a mysterious illness plaguing cattle herds. Simultaneously, he investigated Babesia and Trypanosoma parasites, as well as the tick-borne illness spirochetosis. Koch’s study found that ticks might potentially spread Babesia. Infecting cattle with Texas fever, these parasites laid their eggs in RBCs.

Arsenic and fire for the treatment of sleeping sickness

A year later, in 1906, Koch went back to Central Africa to continue his work against the deadly sleeping disease. David Bruce, a colleague in the field, had previously (1918) identified a trypanosome species as the pathogen and the tsetse fly as the intermediate host. Koch was looking for a cure when he found the arsenic-based organic molecule that is the medicine Atoxyl.

However, the dose needed was very high, and the hazardous side effects were the norm. Instead of addressing the root of the problem, he took a dramatic step and ordered the tsetse fly to be eradicated. Trees and bushes were being cut down and raked out with brutal efficiency all along the East African coast. Tsetse flies feed on blood, so crocodiles were often killed for their meat.

Stroke at age 66

Koch’s extensive international excursions were draining, though. Decades before his death, he showed symptoms of angina, but that didn’t stop him from enduring the rigors of his research excursions.

Sadly, Koch experienced a serious heart attack and complained of shortness of breath and discomfort in the left side of his chest three days after delivering a seminar talk on TB in April 1910. He left for Baden-Baden on May 23 to recuperate at the sanatorium of his friend Dr. Dengler. In the short term, his health seemed to improve in the moderate Black Forest environment. Before supper on May 27, he planned to bask in the sun via the open balcony door. And then the attending physician came upon his body while on rounds.

Robert Koch spent his whole life working to prevent and treat disease. Among the many things he learned from his studies was that burial corpses do not adequately eliminate disease-causing microorganisms and, in fact, promote the development of spores. So, it shouldn’t come as a shock that Koch requested his cremation before he passed away. Ashes were brought from Baden-Baden to Berlin and interred in a mausoleum designed for him at the site of what is now the Robert Koch Institute.

Bibliography

- “Koch”. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Fleming, Alexander (1952). “Freelance of Science”. British Medical Journal.

- Gradmann, Christoph (2006). “Robert Koch and the white death: from tuberculosis to tuberculin”. Microbes and Infection.

- Lakhani, S. R. (1993). “Early clinical pathologists: Robert Koch (1843-1910)”. Journal of Clinical Pathology.

- Tan, S. Y.; Berman, E. (2008). “Robert Koch (1843-1910): father of microbiology and Nobel laureate”. Singapore Medical Journal.

- Lakhtakia, Ritu (2014). “The Legacy of Robert Koch: Surmise, search, substantiate”. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal.