Julius Caesar‘s conquest of Gaul in 51 BC led to its provincialization and integration into the Roman Empire, particularly under Augustus, who created the provinces of Lugdunensis, Aquitania, and Belgica, while the Transalpine region became Narbonensis. But what about the Gallic elites? Did they also succeed in integrating into the imperial elites? What was their relationship with Rome and the emperor?

Sources

Discussing the Gallo-Roman elites presents a source issue, as they are limited. Regarding texts, besides Caesar’s Commentaries, we can cite Livy (who died in 17 AD and was close to Augustus), Strabo (who died around 25 AD), but especially Tacitus and Suetonius, both living in the 2nd century AD.

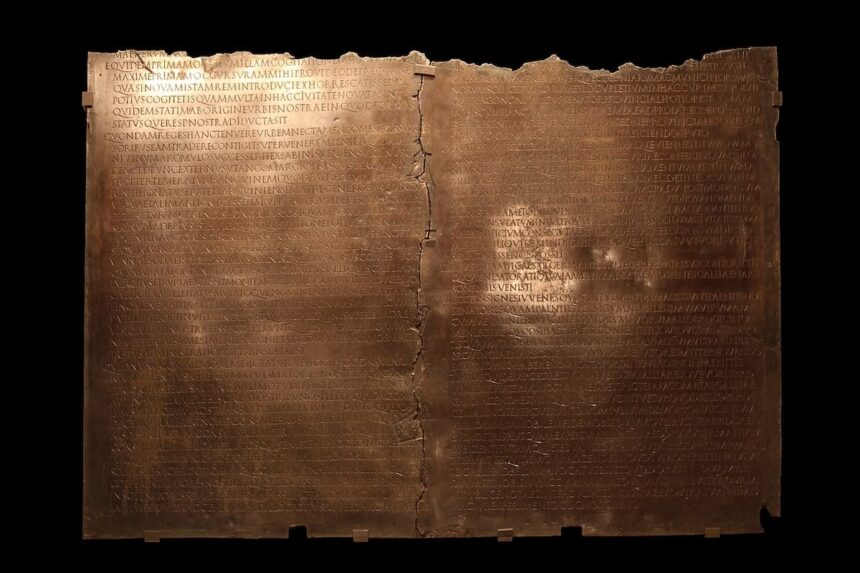

Epigraphy is a major source, as inscriptions were often made by the elites. Lastly, funerary monuments also inform us about the Romanization of these elites.

Here, we will address the Gallo-Roman elites broadly, meaning the Gallic notables following the Romanization of Gaul.

These individuals were socially recognized at the local level for political, administrative, or even broader activities, such as in the economic domain. They became elites by integrating into the highest spheres of power, even reaching the Senate in Rome. We will discuss the Three Gauls and Narbonensis until the Antonine period.

A “Pro-Roman” Gallic Elite?

Even before the Gallic Wars, there was already an elite that could be described as “pro-Roman.” This was particularly the case with the Aedui. Their relations with Rome date back to around 120 BC, when the Romans defeated the Arvernian king Bituitus, benefiting the Aedui. They became privileged partners of Rome, especially in trade, so much so that they were considered “fratres consanguineique populi romani” (brothers and kinsmen of the Roman people). It is no coincidence, then, that Caesar claimed to respond to their call for help in 58 BC, and that after the Gallic Wars, Aedui, with his help, became the first Gauls to enter the Senate.

This Aeduan dominance persisted later under Claudius.

However, the Aedui were not the only ones already close to Rome. From the Republican era, the elites of Narbonensis were culturally and institutionally Romanized, giving them a more positive image in Rome compared to the notables of Gallia Comata, Aedui included.

The Dominance of the Iulii

After his victory, Caesar rewarded his allies with Roman citizenship, a distribution considered generous and criticized, according to Suetonius (a much later source): “Caesar leads the Gauls to triumph, and also to the Curia. The Gauls have left their trousers; they have taken up the broad stripe.” However, the reward was individual, as were grants of magistracies or land. The same applied under Augustus, who founded Autun (Augustodunum), the new Aeduan capital, where universities were created to teach Gallo-Roman notables Latin.

The Gauls elevated to Roman citizenship by Caesar and Augustus were called Iulii, after Julius. They mainly came from a military nobility and landowning aristocracy. The fate of two Aedui is noteworthy: Eporédirix, an Aeduan leader mentioned by Caesar in his Commentaries, was initially pro-Roman (he was with them at Gergovia!), but later joined Vercingetorix and was captured (or his namesake, as Caesar’s account is unclear) at Alesia.

Inscriptions from the 1st century BC later mention a C. Iulius Eporédirix (a Roman citizen from the 40s–30s BC), and we can trace them to the 1st century AD and a figure named Iulius Calenus, who, in 69 AD, was tasked by Vitellius’ victors with negotiating with the defeated at Cremona. This tribune, an Aeduan, seems to be a distant descendant of Eporédirix, illustrating the transition from an Aeduan chief to a Roman knight, a journey of a Gallic family seemingly fully integrated into the Empire.

However, this progression should neither be generalized nor idealized. The integration of Gallic notables into the imperial elite did not happen overnight and was not systematic. This explains the request made to Claudius and his response in 48 AD.

Claudius’ Role in Favor of the Gallo-Roman Elites

Born in Lyon in 10 BC, becoming emperor in 41 AD (after succeeding Caligula), Claudius had close ties with Gaul. Upon his accession, the Gauls of Gallia Comata did not yet have full citizenship, and the notables had no access to the ius honorum (the right to hold public office). Although under Caesar and early Augustus, some Gauls (Iulii from the Three Gauls, Domitii, Valerii, or Pompeii from Narbonensis) had gained equestrian rank and even Senate membership, this ceased after 18 BC. Narbonensis regained this right in 14 AD, but Gallia Comata had not. Hence the request made to Emperor Claudius.

He responded with a famous text, which we know from Tacitus and especially from the Claudian Table, a bronze plaque discovered in the 16th century. Claudius decided to grant the ius honorum to the Aedui (and later to other Gauls). This caused outrage among Roman senators, as Claudius had anticipated, evidenced by his words: “Indeed, I see well in advance the objection that will be made to me…” Gaul, especially Gallia Comata, still had a negative image in Rome, tainted by the terror gallicus.

The Council of the Gauls

As in the rest of the Empire, the imperial cult served as the link between local elites and the emperor.

In 12 BC, Drusus, the father of the future Emperor Claudius, constructed a federal sanctuary for Gaul at Condate, near Lyon. Each year, on August 1st, the elites of the Three Gauls gathered there to celebrate their loyalty to the emperor around the altar dedicated to Rome and Augustus. The Assembly of the Gauls (or concilium) was led by an elected sacerdos, the first being logically an Aeduan, Caius Julius Vercondaridubnus. Under Tiberius, the construction of an amphitheater allowed for games to accompany the assembly’s meetings.

The purpose of creating this Council of Gauls was to integrate and Romanize the indigenous elites. The institution was above the provincial governor (also based in Lyon), answered only to the emperor (to whom it could present requests), and its members were of equestrian rank. It was a mandatory gathering of the Gallo-Roman elites, representing the sixty peoples of Gallia Comata. The Assembly thus played a real political role, and emperors, like Claudius or even Caligula, who in 39 AD organized an oratory competition, attended it.

The Evergetism of Gallo-Roman Elites

Another marker of the Romanization of the Gallo-Roman elites is their practice of evergetism, which refers to the benevolent acts offered to cities (and indirectly to the emperor), often in the form of monuments.

One famous example in Gaul is the amphitheater of Lyon, mentioned earlier. Its construction was initiated in 19 AD by the sacerdos of the Santones, Caius Julius Rufus. This prominent local figure also gifted an arch to his city of Saintes, where, in an inscription, he does not hesitate to compare himself to Germanicus.

Other examples exist, such as a portico donated by the Bituriges to the baths of Néris, a theater in Eu, or another in Jublains.

Transformations and Integration

The integration of Gallic notables was essential for the Empire. By maintaining good relations with the indigenous population, the imperial elites could better exercise their functions in the province. Meanwhile, the local elites could aspire to social advancement.

However, these relations were not always straightforward, especially in Gaul, and often proved asymmetrical. This partly explains the relative integration of Gallo-Roman elites into the imperial elites, with notable differences between Narbonensis and northern Gaul (Gaule chevelue).

Other factors are at play: we previously mentioned the military and landowning background of the Iulii. They appear to have struggled following the revolt of Vindex in 69 AD, which led to repression among their ranks. They lost influence within the Gallo-Roman elite, which began to diversify, integrating, for instance, notable merchants—a trend that intensified under the Antonines. However, these conclusions should be tempered, as sources are scarce.

This heterogeneity of Gallo-Roman elites, combined with a level of urbanization that was less pronounced than elsewhere (and since elites are formed in cities), ultimately resulted in Gaul being less represented within the imperial elites (the equestrian order, and even more so the senatorial order) compared to provinces like Spain or North Africa.