- Sarissa: The Macedonian phalanx spear was pivotal in Alexander’s victories.

- Evolution: Its length increased as it adapted to changing combat strategies.

- Decline: The Romans’ adaptability in warfare brought the sarissa’s eventual end.

The sarissa is a spear that was in use in the early third century BC and was between 180 and 300 inches in length (4.5–7.5 m). During Alexander the Great‘s conquests and the Wars of the Diadochi, this weapon, which had its origins in Macedonia during the reign of Philip II in the middle of the fourth century BC, was employed by the sarissa phalanxes (or “sarissa bearers”). Its proportions increased as it was utilized by the soldiers of the Hellenistic nations.

Sarissa’s Origin

Homer mentions long spears in his account of Hector and Ajax, while Xenophon mentions them in his account of the Chalybes.

The sarissa spear first emerged in the Macedonian phalanx in the years 338–336 BC. It’s conceivable that Philip II adopted the name from the Triballi, whom he fought in 339 BC; Demosthenes reports that the Triballi hit Philip II in the thigh with a sarissa, but this may be an anachronism. Plutarch first mentions Macedonians using sarissas during the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC), although they were only carried by mounted troops. Iron sarissa points, the earliest artifacts from which precise dates can be derived, have also been linked to the Battle of Chaeronea.

In 334 BC, during the Battle of Granicus, Alexander the Great defeated the Persian army with the help of his sarissas for the first time. The length of the sarissas helped the Macedonians fend off Persian attacks while being outnumbered by their foes on higher ground.

-> See also: Boar Spear: A Weapon of Manliness in Ancient Rome

Sarissa’s Appearance and Dimensions

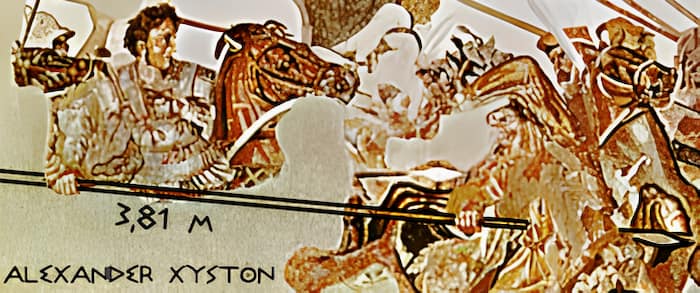

At one end of the sarissa is a leaf-shaped or elongated diamond-shaped iron point, while at the other end is a shorter point. Iron tips were used on Alexander’s sarissas during his war in India, as mentioned by Diodorus and seen in the Alexander mosaic. Manolis Andronikos, who discovered the tomb of Philip II in Vergina, believes that the 18-inch iron spike found there belonged to a sarissa.

However, it’s possible that this is only a ceremonial weapon and not one intended for combat. Some scholars argue that this means the focal point should be smaller (between 4 and 6 inches), with particular reference to the Alexander mosaic.

The Material Used to Make the Sarissa

The original sarissa shaft was likely made of a controversial kind of wood. The male cornel tree (also called cornus mas) is said to be the source material for the sarissa, since it is thick and flexible and was brought to Athens by Xenophon following the expedition of the Ten Thousand (a Greek mercenary unit) from Asia. Then, the material would have been widely adopted across Macedonia. Because of its widespread usage, the Greek poets of the third and fourth centuries BC often used the phrase “cornel wood” to mean “spear.” The shaft of the xyston, a long lance of the Companion cavalry, is made from cornel wood.

However, another legend has it that ash wood was used instead, which is just as malleable and durable as male cornel wood. The Latin poet Stace from the first century AD is cited as the source for this belief about the Macedonians’ use of ash spears. Even if you don’t trust Stace when it comes to military hardware, this is the only ancient source that specifically mentions the kind of wood used to make the sarissa. In antiquity, ash wood was often used, and Macedonia had a plentiful supply. Theophrastus suggests that the length of the longest sarissa is equal to the height of a male cornel, which might lead to the mistaken belief that sarissas were fashioned of cornel wood.

The sarissa was originally 15 pounds (7 kg) in weight and ranged in length from 15 to 18 feet (4.6–5.3 m) (according to Theophrastus, Arrian, and Asclepiodotus). Polybius and Livy state that in the first part of the third century BC, this spear was lengthened to 25 feet (7.6 m). When considering the sarissa’s construction, it’s unclear whether this spear is a single piece or two halves connected together. The second explanation is more feasible given the difficulty of sourcing a straight and robust shaft of such length. Instead, it is more likely that the two halves were joined by a metal ring, an example of which was discovered in Philip II’s tomb.

The sarissa spear was three times longer than the regular 7-foot Dory spear used by other Greek warriors.

-> See also: Rohatyn: A Slavic Bear Spear of the 12th Century

Use of Sarissa in Phalanx Formations

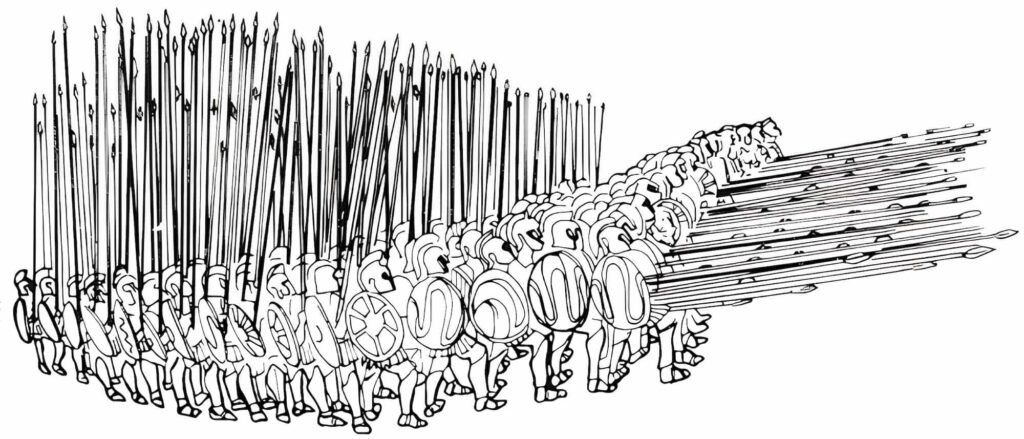

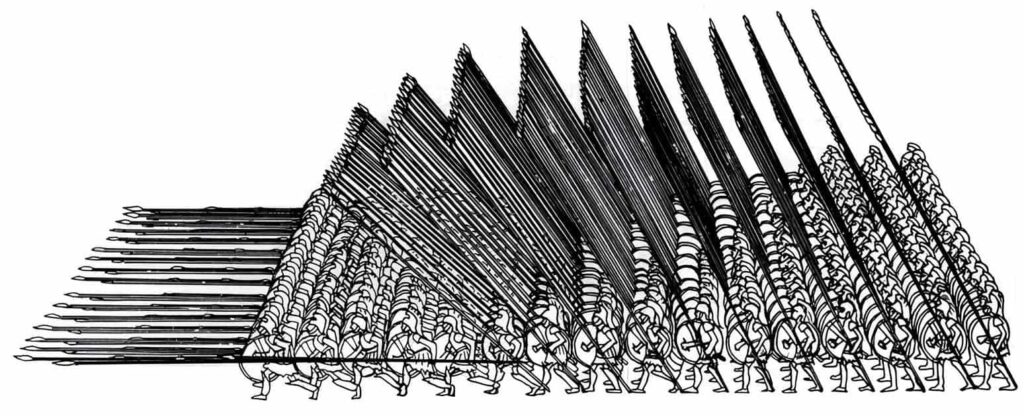

When sarissa bearers were arrayed in a phalanx, the sarissas of the first five ranks protruded beyond the first rank to create a wall of pikes (out of a total of 16 ranks). In order to deflect incoming projectiles, the first five ranks held their sarissas horizontally, while the last two held theirs vertically. The sarissa’s length made it effective in stopping cavalry attacks and keeping infantry at bay by presenting the adversary with an impenetrable and virtually impregnable hedge of pikes.

Heavy armor was unnecessary while using this weapon since the phalanx’s opponents were continually driven back by the formidable mass of iron and wood. Because the sarissa fighters just required a spear and light armor, a large number of troops could be recruited at a cheaper cost. Phalanx warriors only employed the sarissa in close-quarters combat; in open fields, they relied on the customary lance, the xyston.

Fighting Using the Sarissa Spear

Phalanx warriors were able to cross great distances quickly and undetected by the adversary since their sarissas protected them from melee assaults and hostile missiles. Their efficacy in charging was further improved by their enhanced velocity. Furthermore, the masses of the sarissa carriers united during the charge, allowing them to totally break through the enemy’s formation because of how closely they were packed together. The sarissa could be fastened to the ground with the help of the short point at its base, which could also be used to replace the top point if the latter ever broke.

Advantages

It was almost hard to remove the sarissophoroi, or sarissa-bearing infantry, from their defensive positions. This was due to the fact that their sarissa wall was too thick, lengthy, and compact for the attackers to break through. When deployed, the phalanx could form two columns of five rows of lances, which was twice as dense as a unit of Roman legionnaires, for example. If an enemy soldier made it between the first rank’s two sarissas, he would be met with fierce blows from the second, third, fourth, and fifth ranks, making their mission almost impossible as they were repeatedly driven back.

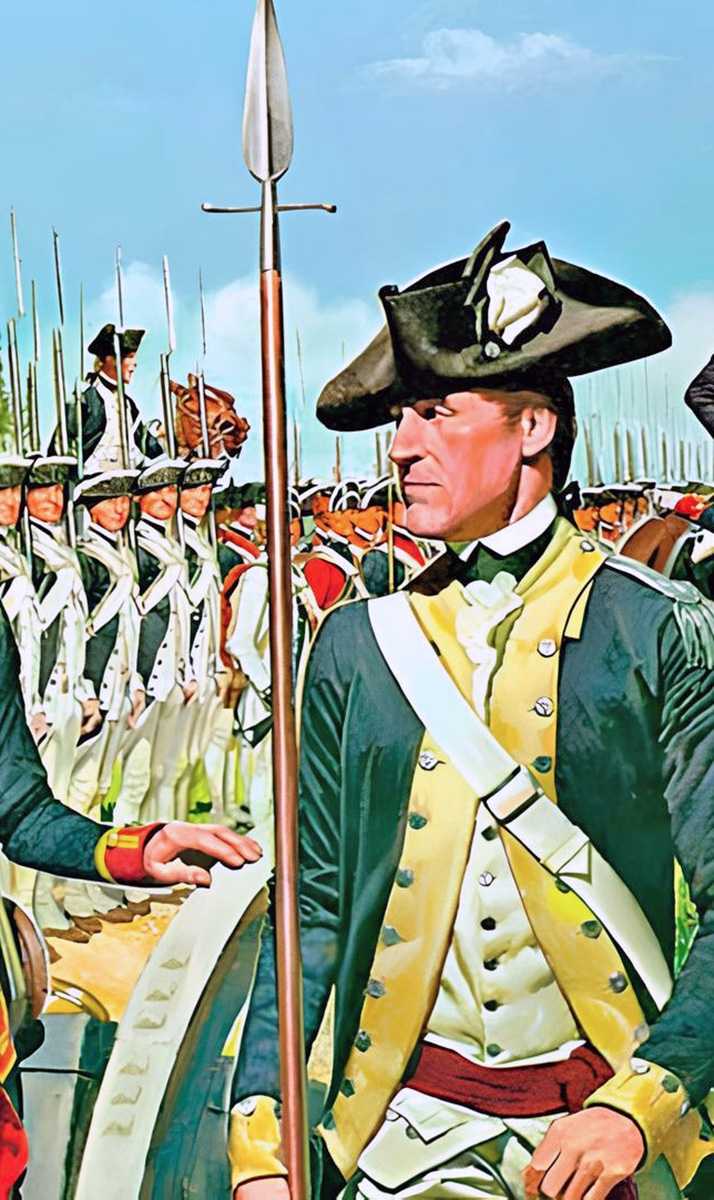

By substituting sarissas for the xyston, the Macedonian cavalry (Companions or prodromoi, also known as sarissophoroi) gained an edge in frontal attacks even against hoplites. The lance was held in the center, and the attack could come from above or below, as seen on Alexander’s tomb and the Alexander mosaic.

Weak Sides

Attacking the sarissophoroi’s weak sides was the only option to defeat them, since a head-on assault would have been disastrous against their pike-studded phalanx. It seems that no frontal attack on a Macedonian phalanx was ever successful. Its main downfalls came from being surrounded, as in the battles of Cynoscephalae (197 BC), the Nile, and Corinth, or from a lack of phalanx cohesiveness, as at Magnesia (190 BC) and Pydna (168 BC).

Polyaenus recounts a ruse used during the campaign of the Spartan general Cleonymus and the Epirus king Pyrrhus in Macedonia in the 270s BC:

2.29 – At the siege of Edessa, when a breach was made in the walls, the spear-men, whose spears were sixteen cubits long, sallied out against the assailants. Cleonymus deepened his phalanx, and ordered the front line not to use their weapons, but with both hands to seize the enemy’s spears, and hold them fast; while the next rank immediately advanced, and closed upon them. When their spears were seized in this way, the men retreated; but the second rank, pressing upon them, either took them prisoner, or killed them. By this manoeuvre of Cleonymus, the long and formidable sarissa was rendered useless, and became rather an encumbrance, than a dangerous weapon.

Polyaenus: Stratagems – Book 2

However, the Spartans were not dealing with the Macedonian phalanx here. The strength of the phalanx in the battle of the Romans against the Macedonian army in 168 BC is described by Plutarch:

The Macedonians in the first lines had time to thrust the points of their sarissas into the shields of the Romans and thus became unreachable for their swords. The Romans tried to sword away from the sarissa, or bend them to the ground with shields, or push them aside, grabbing them with their bare hands, and the Macedonians, clenching their spears even tighter, pierced through the attackers, – neither shields nor armor could protect from the blow of the sarissa.

The Reason Why Later Sarissas Were Made Even Longer

Following Alexander the Great’s conquests, armies from India to Sicily adopted phalanx formations modeled after those of the Macedonians. Battles between Alexander’s successors, the Diadochi, occurred in Paraitakene (317 BC), Gabiene (316 BC), Gaza (312 BC), and Ipsus (301 BC), were the scenes of the first Macedonian-style phalanx fights.

However, the phalanxes were rendered mostly ineffectual in these “fratricidal” fights, with comparable and extremely light equipment causing mutual destruction upon collision. When two soldiers with identical sarissas collided, they could no longer avoid each other’s hits, lowering the spear’s effectiveness.

The sarissas of phalanxes in various Hellenistic kingdoms became steadily longer to outdistance the enemy’s shorter pikes and counteract this trend. By 274 BC, during the early years of the reign of Antigonus II Gonatas, sarissas had grown in length from 16.5 to 25 feet (5–7.5 m). Even with extensive training, subsequent sarissas were too heavy and unwieldy to handle, despite their appearance being quite light and controllable.

Because of this, these soldiers were eventually relegated to defensive roles on the battlefield. To be more effective against other phalanxes, they gave up mobility and flexibility. In addition, shields and armor were fortified greatly to compensate for the phalangites’ vulnerability to strikes from opponents using equally long sarissas. In addition to their very long pikes, phalangites in wars like Pydna (168 BC) and even earlier at Cynoscephalae (197 BC) were almost as well armed as Roman legionnaires.

A Decrease in the Use of Sarissa

The Romans finally triumphed over these phalanxes because they had become too large and cumbersome to be effectively used (in stark contrast to Alexander’s phalanxes).

The Roman legions were far more adaptable, allowing them to surround the phalanxes and assault their flanks. Seleucid phalanxes played a crucial defensive role in both Magnesia (190 BC) and Thermopylae (191 BC), when they stood immobile behind their barrier of points. At Pydna (168 BC), the Macedonian infantry was hampered by its own disordered bulk, rendering it unable to respond as quickly as it had against the Persians and Greek hoplites.

Alexander’s phalanxes never appeared to be hampered by such challenges, as they were able to successfully traverse the East despite its harsh geographical conditions, fight in forest-covered Macedonia, cross rivers in the midst of battle (Granicus and Hydaspes), and face a much larger enemy (battles of Ipsus and Gaugamela) without experiencing cohesion problems, and were consequently undefeated for the first two centuries of their history. Despite his unreliability, Livy said that the late phalanxes were “unable to make a half-turn.”

While the Roman armies emphasized movement and adaptability, the Hellenistic rulers’ never-ending armament competition only reduced the phalangites’ durability, mobility, and the sarissa’s tenacity. The phalanxes envisioned by Philip II had died out by the end of the third century BC. Even after the Kingdom of Commagene was dissolved in 72 AD, the sarissa was still in use in certain areas. This was true even after the acquisition of the Kingdom of Egypt by Rome in 30 BC.

What Left Behind from the Sarissa Spear

-> See also: Ahlspiess (Awl Pike): An Anti-Armor Spear of the 15th Century

The sarissa had a major impact on the Swiss pikemen of the Middle Ages. Through their victories against greater European forces, they helped hasten the end of the chivalric period. Swiss pikemen, widely regarded as the best infantry of their day, broke away from the Holy Roman Empire and fought as mercenaries throughout Europe.