Cicero’s “De divinatione” (44 BCE), which rejects astrology and other supposedly divinatory techniques, serves as a rich historical source for understanding the conception of scientificity in classical Roman antiquity. Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE) compiled in his “Naturalis Historia” the science of ancient Greece. Although science in Ancient Rome did not undergo the same development as in Hellenic culture, it was a civilization with significant advances in the systematization and organization of classical knowledge.

The Romans excelled in applied technology, particularly in agriculture, public works, and military technology: hydraulic mills, central heating systems, and insulation against housing humidity; catapults, crossbows, and assault towers mounted on wheels; lighthouses in ports; and, above all, a road construction system with stone pavement amalgamated with mortar, curbs, and drainage ditches, which has allowed a substantial preservation of the Roman road layout.

The development of engineering in high-construction instruments such as pulleys, cranes, and mills, as well as the evolution of the arch in architecture, set precedents in shaping technology and applied science. The organization of cities and the establishment of new transportation and communication mechanisms are also part of their engineering developments. Pliny the Elder’s work stands out as an heir to Hellenic natural philosophy, compiling over 37 volumes and texts with various observations on natural philosophy in Latin. Claudius Ptolemy, in “Almagest,” describes a model of planetary motion, popularizing the geocentric idea of the universe. The establishment of the Roman calendar based on solar cycles, as well as its own mythology, is also part of Rome’s scientific heritage.

In medicine, they drew from the various influences of the Hellenic schools of Hippocrates and Asclepiades. The fear of Hellenization by Cato and other Roman intellectuals kept medical practice unregulated for much of the republic and the empire. Medical education was private, and its performance was based on non-systematic practices. The main author of the period was Galen, who systematized and translated the works of Hellenic medicine into Latin during his lifetime, including detailed descriptions of animal and human dissections. These works had a significant impact during the Middle Ages. There is also evidence that Celsus practiced plastic surgery techniques during his lifetime.

Constructions

The most important Roman constructions were:

- Theaters, where works of art were performed.

- Amphitheaters, where gladiators fought.

- Circuses, where chariot races took place.

- Baths (Thermes), where people bathed and exercised.

- Triumphal arches, commemorating historical events and figures.

- Aqueducts, for channeling and supplying rainwater.

- Gardens, where various crops were introduced.

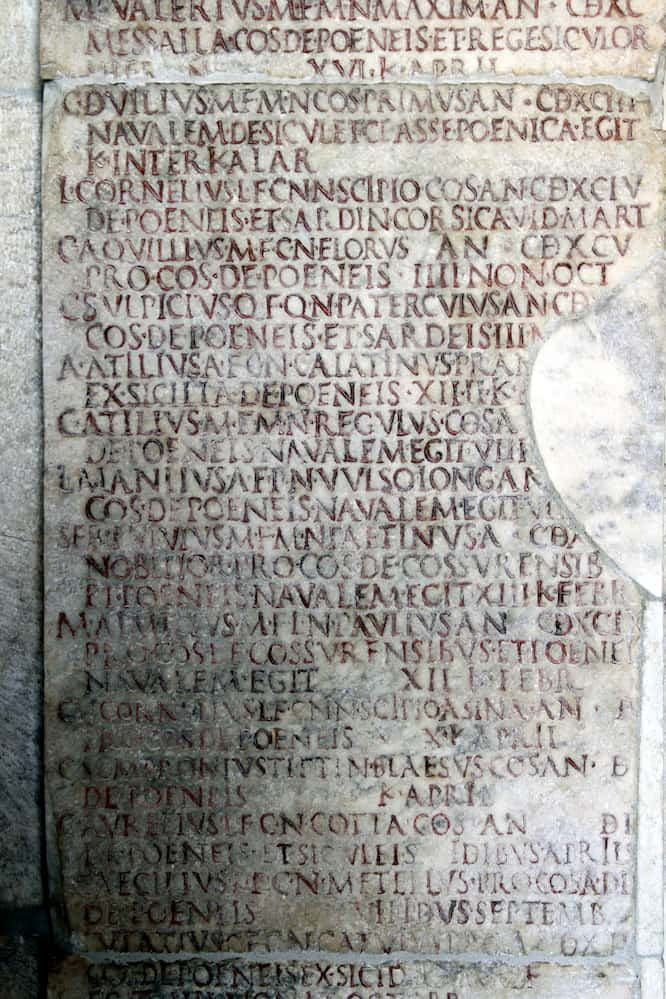

Calendar

Detail of the Fasti Consularii (a calendar that counted years based on the names of the consuls who had held office), originally located in the Roman Forum (currently in the Capitoline Museums). The Roman calendar was the first system to divide time in ancient Rome. According to mythic tradition, the Roman calendar was created by one of its first two kings, Romulus. The early Roman calendar set the duration of months at 29 days, 12 hours, and 44 minutes, with lunar months of 29 or 30 days. The month was the larger fraction, and the day was the smaller one, although later it was divided into hours.

The Romans considered the day to begin at midnight. When establishing the year (from “annus,” meaning ring), they set its duration at 10 months (decimal system). However, later, under Greek influence, they transitioned to a year of 12 months, with 368 days and ¾ of another day, with months alternating between 30 and 29 days. Every two years, a year with 13 months was added, progressively adjusting the system by removing or adding days. Thus, a year was established that began in spring (in the month dedicated to the god of war Mars, i.e., the month “martius” = March), followed by the opening month (“aprilis” = April), the month of growth (“maius” = May), and the month of flourishing (“junius” = June).

The months then continued in order from the fifth to the tenth: quintilis (July), sextilis (August), septembris (September), octobris (October), novembris (November), and decembris (December). This was followed by the month for the opening of agricultural work (“januarius” = January) and the month of purifications (“februarius” = February). If another month was added, it had no name but was called “mercedonius” as it was dedicated to payment.

With progressive adjustments, months with 31 days were established (March, May, July, and October), those with 28 days (February, which had 29 days every four years), and those with 29 days (the others), with an intercalated month of 27 days every two years. Thus, the first and third years of the cycle had 355 days each; the second year had 383 days, and the fourth year had 382 days, totaling 1474 days. Each month was divided into weeks ranging from 4 to 9 days: the second and fourth weeks of the month were 8 days long, the third was 9 days (except in February, which was 8, and in the intercalated month, which was 7), and the first week was 6 days in months with 31 days and 4 days in others.

The announcement of the duration of the first week was called the announcement of the calends; the ninth day of the nine-day weeks was called nonae or nonas; and the first day of the third week was called idus (or ides). Each period of five years was called a lustrum, as sacrifices (lustrum) were made the year after the census review, which occurred every four years.

This system was used until 46 BCE, when Julius Caesar, who was then a dictator and Pontifex Maximus, decreed a calendar reform, advised by the Greek Sosigenes of Alexandria, creating the Julian calendar.

Medicine

Roman medicine refers to the medical practices developed in ancient Rome. The Etruscan civilization, before importing knowledge from Greek medicine, had barely developed a medical corpus of interest, except for a notable skill in dentistry. However, the increasing importance of the metropolis during the early expansion attracted significant Greek and Alexandrian medical figures, ultimately shaping Rome into the primary center for medical knowledge, clinical practice, and education in the Mediterranean region.

The most important medical figures in ancient Rome were Asclepiades of Bithynia (124 or 129 BCE–40 BCE), Celsus, and Galen. Asclepiades, openly opposing the Hippocratic theory of humors, developed a new medical thought based on the works of Democritus, the Methodic School, explaining illness through the influence of atoms permeating the body’s pores, anticipating the microbial theory. Some physicians associated with this school were Themison of Laodicea, Thessalus of Tralles, or Soranus of Ephesus, the author of the first known biography of Hippocrates.

Between 25 BCE and 50 CE, another significant medical figure lived: Aulus Cornelius Celsus. There is no record of him practicing medicine, but a medical treatise (De re medica libri octo) is preserved, included in a larger, encyclopedic work called De artibus (On the Arts). This medical treatise includes the clinical definition of inflammation that has endured to this day: “heat, pain, swelling, and redness” (sometimes also expressed as “swelling, redness, burning, and pain”). It also describes plastic surgery operations, the removal of nasal polyps, tonsils, etc.

With the onset of the Christian era, another medical school developed in Rome, the Pneumatic School. While the Hippocratics attributed disease to liquid humors and the atomists emphasized the influence of solid particles called atoms, the pneumatics saw the cause of human pathological disorders in the pneuma (gas) entering the body through the lungs. Followers of this line of thought included Athenaeus of Attalia and Aretaeus of Cappadocia.

In Rome, the medical profession was already organized (reminiscent of the current specialization divisions) into general physicians (medici), surgeons (medici vulnerum, chirurgi), oculists (medici ab oculis), dentists, and specialists in ear diseases. There was no official regulation to be considered a physician but starting with the privileges granted to physicians by Julius Caesar, a maximum quota per city was established. Moreover, Roman legions had a field surgeon and a team capable of setting up a hospital (valetudinaria) on the battlefield to tend to the wounded during combat.

One of these legionary doctors, enlisted in Nero’s armies, was Pedanius Dioscorides of Anazarbus (Cilicia), the author of the most widely used and known pharmacological manual until the 15th century. His travels with the Roman army allowed him to compile a vast collection of herbs (around six hundred) and medicinal substances to draft his monumental work, De materia medica (Dioscorides).

But the quintessential Roman medical figure was Claudius Galen, whose influence endured until the 16th century. Galen already practiced dissection, but with animals, as the anatomical study of human corpses was strongly frowned upon. This led him to make certain anatomical and physiological errors that persisted until Vesalius. He was the primary exponent of the Hippocratic school, but his work is a synthesis of all the medical knowledge of his time. His treatises were copied, translated, and studied for the next thirteen centuries, making him one of the most important and influential physicians in Western medicine.

Judging by what was found in the home of a Pompeii doctor, surgical materials were not excessively rudimentary. There are indications that they knew about the dental mirror and the antiseptic properties of certain ointments. Medical education was private, and there were no official titles. Anyone could practice medicine, even during the imperial era, when physicians were exempt from taxes and military service. Most doctors were Greeks and Jews. There was not significant progress in medicine in Roman civilization because there was no interest in experimental research, and there was an obsession with writing medical books in verse. Sammonicus (the inventor of the magic formula Abracadabra) introduced this trend that would dominate the Middle Ages.

Regarding healthcare organizations, the significant Roman contribution was the hospital system. However, its beginnings were nothing more than the establishment of a shelter for poor patients to die in, known as the illa Tiberiana. With the expansion of the empire, military hospitals were established in strategic locations. Following these, charitable hospitals emerged. The first was founded by Fabiola of Rome, marking the first documented precedent of “social medicine” and making her one of the most famous women in the history of organized medicine. In this hospital, the poor received free care.

Archaeological excavations revealed the plan and arrangement of this unique building, where rooms and corridors for the sick and poor were orderly grouped around the main structure, organized into sections according to different classes of patients. According to historian Camille Jullian, the foundation of this hospital is one of the most significant events in the history of Western civilization.

According to Henry Chadwick, emeritus regius professor at the University of Cambridge and historian of early Christianity, the practice of charity expressed prominently through the care of the sick was likely one of the most powerful reasons for the spread of Christianity.

By the year 251, the Church of Rome was supporting over 1,500 people in need. Despite the existence of Roman proto-field hospitals, the Empire lacked social hospital awareness until the foundation of the first large Christian hospitals. In the East, the Basilias Hospital was founded near Cappadocia (inspired by Basil of Caesarea), and another hospital in Edessa was founded by Ephrem the Syrian, with three hundred beds for plague victims.

A crucial contribution of Roman public medicine must be highlighted: Among the leading Roman architects (Columella, Marcus Vitruvius, or Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa), there was a belief that malaria spread through insects or swampy waters. Under this principle, they undertook public works such as aqueducts, sewers, and public baths aimed at ensuring a supply of quality drinking water and an adequate sewage disposal system. Modern medicine will validate their insight almost twenty centuries later when it is demonstrated that the supply of clean water and the sewage disposal system are two key indicators of a population’s health level.