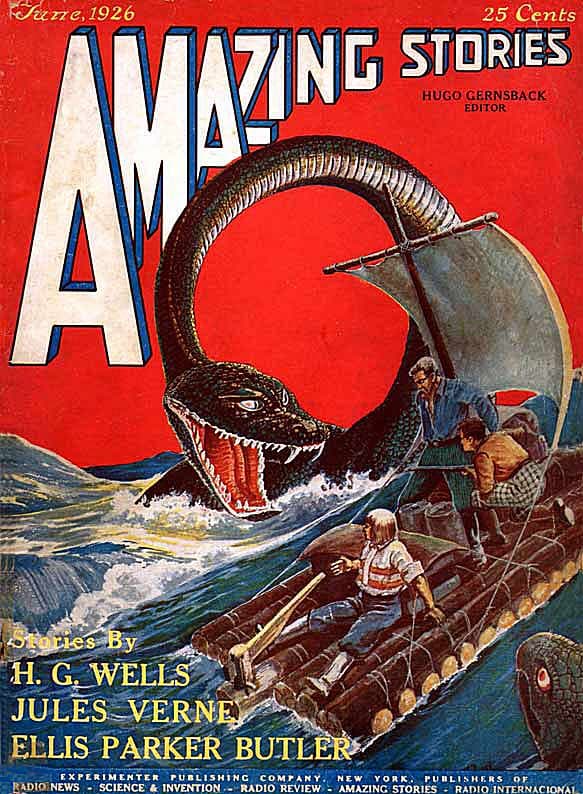

The sea serpent, a legendary sea creature resembling a land snake, is one of the main subjects of interest in cryptozoology. Reports of alleged sea serpent sightings come from various parts of the world and different times (these creatures were said to have been seen for hundreds of years). In his latest work, Bruce Champagne estimates that over 1200 individuals have reported their sightings. Sea serpents were claimed to be seen from the decks of ships as well as from the shores. Observers included both individuals and groups, among which sometimes were scientists. Despite numerous reports, there is a lack of physical evidence for the existence of these animals. Their presence has not been officially confirmed and is regarded by science as one of the maritime legends.

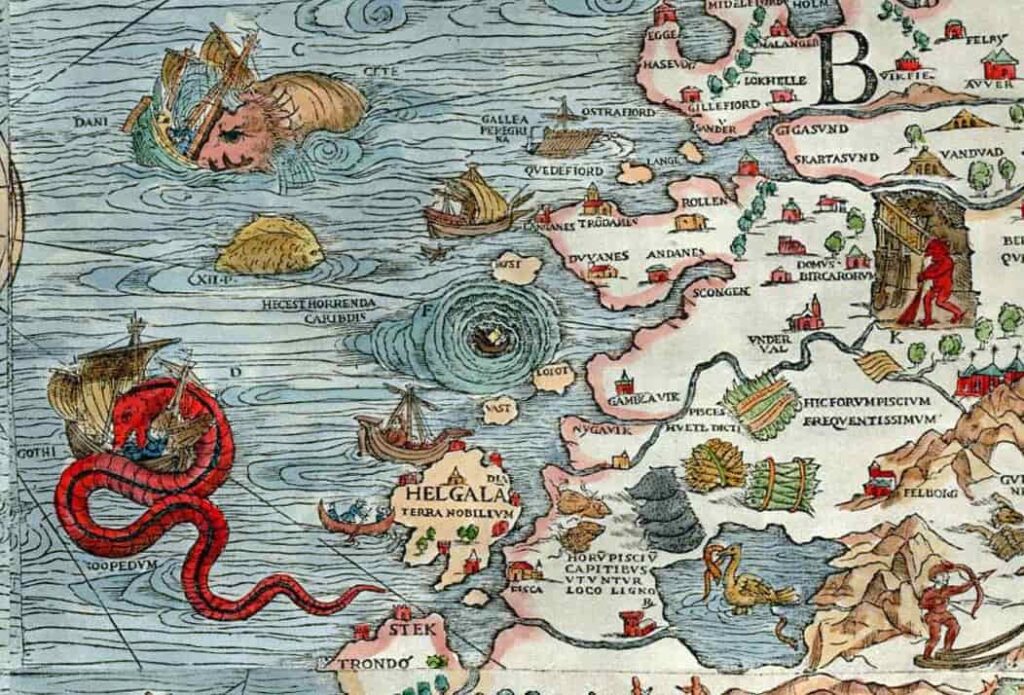

The most famous depictions of sea serpents come from engravings in the works of 16th, 17th, and 18th-century researchers such as Olaus Magnus, Erik Pontoppidan, and Hans Egede. In their time, almost everyone was convinced of the existence of sea serpents, and elaborate illustrations of these creatures adorned most maritime maps. However, science did not confirm their existence, yet many people still maintained that these animals inhabit the seas and oceans.

Particularly well-known were cases of the so-called Gloucester sea serpent or Caddy. Reports of alleged sea serpent observations from the decks of HMS “Daedalus,” HMS “Plumper,” or “Avalanche” were also notable. The first scientific publication dedicated to these alleged creatures was authored by Anthonid Cornelis Oudemans in 1893. Subsequently, others like Bernard Heuvelmans, Loren Coleman, and Patrick Huyghe followed suit. There were also a few purported photographic pieces of evidence for the existence of sea serpents. However, their authenticity was questioned by experts.

Earliest Sea Serpent Reports

In Norse mythology, Jormungand or Midgårdsorm was a sea serpent so long that its body encircled the entire world, Midgard. Some maritime tales described instances where sailors mistook its back for a chain of islands. Sea serpents also frequently appeared in Scandinavian folklore, especially Norwegian.

In 1520, Catholic Archbishop of Trondheim, Erik Walkendorf, wrote a letter to Pope Leo X describing sea serpents.

The smallest of them is 60 feet long and 10 feet thick. The square head is longer than the body. They are gray and only seen when the air is clear and the sea is calm; they are vile creatures that kill humans.

In the 16th-century work of Swedish clergyman and writer Olaus Magnus, titled Carta Marina, information about many maritime monsters, including sea serpents, is presented. Furthermore, in his 1555 work, History of the Northern Peoples, Magnus included the following description of a Norwegian sea serpent:

Those who sail to the coast of Norway for trade or fishing tell incredible stories of a snake of terrifying proportions, 200 feet long and 20 feet wide, dwelling in crevices and caves near Bergen. In bright summer nights, this serpent leaves its caves to devour calves, lambs, and pigs or ventures into the sea, feasting on maritime nettles, crabs, and similar marine creatures. It has long hair hanging from its neck, sharp black scales, and fiery red eyes. It attacks ships, seizes people, and swallows them, rising from the water like a column.

Lutheran missionary Hans Egede, in his book Det gamle Groenlands nye Perlustration eller Natural Historie from 1746, wrote about a sea serpent:

…a terrifying sea monster… that was seen in 1734 beyond the colony. It was a colossal creature: its head was a yard long and protruded from the water. The body was as wide as a ship and three to four times longer than its width. It had a pointed snout and blew like a whale. It had large, wide limbs, and its body appeared to be covered in scales, with very tough skin. The overall shape was serpentine. When it submerged, it surged back, and then raised its tail above the surface for the length of a ship.

Erik Pontoppidan, Bishop of Bergen, popularized tales of the Norwegian sea serpent in the 1750s. In two volumes of “A Natural History of Norway,” he included many descriptions of this legendary creature. He claimed to have received data directly from fishermen and merchants – people who allegedly saw the creature with their own eyes. Pontoppidan describes in one chapter a sea serpent, which he calls serpens marinus or Aale-tust:

I was among those who doubted the reality and existence of the sea serpent, but in the end, my doubts were dispelled by solid evidence. (…) Hundreds of our best sailors and fishermen saw the sea serpent with their own eyes. I met many people from our fjords in the north; they were able to answer my questions, and their descriptions of the creature were the same. (…) I must assure you of the truth of the existence of this serpent before I begin to describe it. This marine creature resides in the depths, except for July and August, which are sometimes its playtime. It emerges when the sea is deadly calm but submerges as soon as the slightest disturbance appears on the surface.

Pontopiddan described several encounters with the alleged sea serpent. In 1745, north of Bergen, a fisherman reportedly noticed a long creature floating close to his boat. The creature had a head resembling a seal’s and a thin body the length of the boat. Another account dates back to around 1750. Another fisherman supposedly observed the monster from such a close distance that he could touch it. Pontoppidan also speculated that sea serpents might not be related to land snakes at all. In his opinion, these creatures could be representatives of entirely different types or species. Another clergyman, Knut Leem, who dealt with the Lappish language, in his 1767 book titled “Description of the Sami People in Finnmark” wrote:

The sea serpent known from the southern coasts is also seen in Finnmark, a terrifying sea monster, like the Kraken. It is about 240 feet long, with black eyes and a head the size of a whale but shaped like a snake. Its neck is narrower than the body and has long, light green hair hanging on both sides of the neck, similar to a horse’s mane. The back is also light green, but the belly is rather whitish. It is often seen in calm weather, its spiral body partially floating above the water, partly hidden in it. People fear this dreadful sea creature and should keep away from it if possible.

Sea Serpents in Later Times

Gloucester Sea Serpent

One of the most well-known alleged sea serpents is the so-called Gloucester Sea Serpent. It is said to appear in the Atlantic Bay of Gloucester, north of Boston, and off the coast of New England. The first reports of encounters with this creature date back to the 17th century. In 1641, Obadiah Turner described such a creature. According to his account, witnesses saw the most magnificent serpent near Lynn, Massachusetts. The alleged monster was about 88 feet long.

The first mention of the sea serpent that appeared in print comes from John Josselyn’s work titled “An Account of Two Voyages to New England” from 1674, in which he described conversations with residents of the colonies around Massachusetts Bay. They mentioned a creature sunning itself on a rock at Cape Ann.

In 1779, during the American Revolutionary War, the crew of the American ship “Protector” reportedly encountered a sea serpent, which they fired upon. According to reports, the creature escaped without visible injuries. Another account from 1780 comes from Captain George Little of the frigate “Boston,” who allegedly encountered a strange creature in Broad Bay, off the coast of Maine. He described the encounter as follows:

At daybreak, I discovered a large serpent or monster, emerging from the bay, on the surface of the water. (…) I went into the boat and followed the serpent. When I was a hundred feet away from it, the sailors were ordered to shoot at it, but before they were ready to do so, the serpent dived. It was no more than 45-50 feet long; the widest diameter of its body, I think, was 15 inches; its head was almost human-sized, held 4 to 5 feet above the water. It resembled a common black snake.

In August 1817, two men reported an encounter with a sea serpent. Around the same time, Amos Story’s wife observed an object through a telescope, initially mistaking it for a floating tree trunk. When she looked again a few moments later, the supposed trunk had disappeared. During the same period, Mary Row claimed to have seen a monster approximately 330 feet long with a head resembling that of a horse. On the same day, Amos Story himself witnessed the alleged sea serpent:

Its head seemed to be of a shape very much like that of a sea turtle, raising it ten to twenty inches above the water’s surface. Its head, from that distance, appeared larger than the head of any dog I have ever seen. From the back of the head to the next visible part of the body, which I estimate, was three or four feet in length. It moved very rapidly in the water, I would say a mile or two at most, in three minutes.

In the same year, on August 12, sailor Solomon Allen III also claimed to have seen a strange creature. According to his account, the sea serpent had a head similar to a rattlesnake but the size of a horse’s. Allen stated that the creature moved in a chaotic manner, sometimes winding on the water’s surface and sometimes swimming straight. Two days later, another sailor, Matthew Gaffney, claimed to have shot the sea serpent.

According to his account, he aimed at the creature’s head, which, when wounded, began to swim towards the ship. However, just before the boat’s side, the creature dove and emerged again at a considerable distance from the vessel. Gaffney mentioned that the sea serpent’s body reminded him of a caterpillar, as it was divided into barrel-like segments.

The Gloucester Sea Serpent case gained such notoriety that in 1817, the Linnean Society of London, specializing in the taxonomy of newly discovered species, decided to investigate. On August 18, the creature was given the Latin name Scolophius atlanticus. The basis for this was the discovery of a deformed land snake, which the Society members considered to be a juvenile form of a large sea creature. When the true nature of this finding came to light, researchers became the subject of widespread mockery.

William Crafts even wrote a play titled “The Sea Serpent; or, Gloucester Hoax: a Dramatic jeu d’esprit in Three Acts.” For many, these events became evidence that the entire Gloucester Sea Serpent affair was nothing more than a common hoax. However, new reports of encounters with the alleged monster continued to emerge. Soon after, on August 14, 1819, Samuel Cabot claimed to have seen a creature about 78 feet long with a head resembling a snake’s head off the northeastern coast of Massachusetts.

In 1912, the Gloucester Daily Times reported in an article titled “The Sea Serpent is No More: Killing the Legendary Animal” that the monster had become entangled in the nets of the Boston fishing steamer “Philomena.” After its destruction, the creature was said to attack the ship. According to the press account, sailors from the “Philomena” and two other assisting vessels, the “Victor” and “Ethel,” killed the sea serpent after two hours of struggle. Its body, 50-65 feet long, was said to sink into the ocean depths.

Another article from Gloucester Times dated June 12, 1912, titled “Sea Serpent Seen Near Thatchers,” describes the observation of a sea serpent by the crew of the ship “Flora,” commanded by Captain George Brooks. The sailors claimed to see only part of the creature’s body, about 25 feet long.

From the 19th century, there are many reports of alleged Gloucester Sea Serpent encounters. For example, in 1817, there were 18 reports of supposed sightings; in 1839, 12; in 1875, 9; and in 1886, 13. Over a hundred years, approximately 190 reports were recorded. In the 20th century, such reports became noticeably rarer – 56, with the majority occurring before 1950.

One of the last accounts is from May 4, 1997, when two fishermen, Charles Bungay and C. Clarke, were fishing in Fortune Bay, located on the southern coast of Newfoundland. At one point, they saw something they mistook for bags of garbage floating on the water’s surface. They decided to pull it aboard, only to realize it was a living creature that raised its head and stared at them. They estimated the length of the creature’s neck to be almost 6.5 feet, and its head reminded them of a horse. According to the fishermen’s account, the creature looked at them and submerged underwater.

There is a lack of more credible reports of encounters with the alleged creature in the last 20 years. Supporters of its existence argue that the Gloucester Sea Serpent most likely became extinct or moved elsewhere.

Caddy

Another well-known case of a supposed sea serpent is Caddy, a creature said to appear in the Canadian Cadboro Bay (hence the name, also proposed as the Latin name Cadborosaurus willsi) in British Columbia. It is typically described as an elongated creature with fins and a crest on its back. A distinctive feature of Caddy is said to be its head, resembling that of a camel. Witnesses usually estimate the length of the creature to be between 40-65 feet. According to Edward Bousfield and Paul LeBlond, between 1881 and 1994, 178 observations of this supposed sea serpent were recorded.

Cryptozoologists are intrigued by the frequency of encounters with Caddy and the precision and coherence of the reports about observing this creature. In many cases, multiple individuals claim to have seen the same creature, sometimes several dozen people. One report from October 26, 1895, describes an encounter in Bellingham Bay where Caddy was seen by 17 people simultaneously. Another observation reportedly occurred in 1933 when two individuals observed a terrifying creature with a camel-like head from their yacht. In 1934, two government officials claimed to have seen two monsters each measuring 65 feet in length.

Several times, remains believed to be from Caddy were found. In October 1937, in Vancouver, the stomach of a killed sperm whale contained a 20-foot body of an unknown creature. It had a cylindrical shape, a head resembling a camel, and a tail with a fin. A photograph of this carcass was taken, but what happened to it afterward is unknown.

Scientists have been unable to identify the remains visible in the photograph. Similar cases occurred in 1936 (the Fircom carcass) and in 1947 (the Effingham carcass, now considered the remains of a basking shark).

In 1939, Captain Paul Sowerby claimed to have encountered Caddy at sea:

“We were heading north, and about thirty miles off the shore, we saw this thing sticking about four feet out of the water. So, I went down to it and looked at it. At first, it looked like a polar bear with shaggy hair. When we had it on our starboard — and the water was as clear as crystal — it looked like a column submerging at least forty feet and with huge eyes. I had an old Newfoundlander as a mate who said, ‘Do you see those big eyes?’ I didn’t notice the snout and nose, just those big eyes.”

Most Caddy observations are relatively well-documented. For instance, on February 13, 1953, ten people claimed to have seen it from various angles, and their accounts were consistent. In the 1980s, the number of reports decreased, but Caddy is allegedly still spotted to this day. In the 1980s and 1990s, oceanographer Paul LeBlond from the University of British Columbia and marine biologist Edward Bousfield from the Royal British Columbia Museum conducted research on this phenomenon. According to them, Caddy must be an unidentified marine mammal.

Alleged Sea Serpent Encounters

Apart from the American Atlantic coast, sea serpents have purportedly been observed in many other locations. Reports of encounters with these creatures differ from alleged observations of other unknown animals not only in the high number of such reports but also in the fact that many were conducted by several people simultaneously for an extended period. Instead of one or a few witnesses claiming to have seen the creature for a moment, some observations include reports from dozens of people who claim to have observed sea serpents for several hours. In many cases, these observations are well-documented and have been considered more than just ordinary maritime legends. However, most of them occurred at a time when photographic documentation was challenging or outright impossible.

HMS “Daedalus”

On August 6, 1848, the frigate HMS “Daedalus” was en route to St. Helena. Near the Cape of Good Hope, Captain Peter McQuahe and the crew claimed to have seen an enormous sea serpent. According to their account, the creature swam parallel to the ship, with its head raised four feet above the water’s surface. The sailors estimated that beneath the head, there was a body about 20-foot long. The sea serpent swam so close to the “Daedalus” that the witnesses could examine it closely. They described it as having a brown color on the back, but yellowish-white on the throat and belly. The creature accompanied the vessel for about 20 minutes. The sailors also claimed to have noticed something like a mane on the serpent’s back. The incident gained considerable attention in the mid-19th century, even catching the interest of the London Times, which dedicated a significant article to the event.

Around the same time, biologist Sir Richard Owen also investigated the matter and concluded that the “Daedalus” crew members did not see an unknown scientific creature but encountered a sea elephant on their way. Owen argued that reports from individuals without zoological education were unreliable. According to him, sailors had never seen a massive sea elephant swimming in the open sea, so they mistook it for an unknown creature. Owen assessed the credibility of sea serpent reports on par with accounts of ghost encounters. The Times published his article, and McQuahe later responded on the same pages, maintaining his previous description of the sea serpent and denying that it could be a sea elephant, optical illusion, or any other explanation.

HMS “Plumper”

Another case of a supposed sea serpent encounter was described in the Illustrated London News on April 10, 1849. It recounted events allegedly occurring a year earlier in the North Atlantic when the HMS “Plumper” encountered a sea monster resembling a serpent on its course. A naval officer described the supposed creature as follows:

“Being west of Oporto (Portugal), I saw a long, black creature with a sharply pointed head, moving slowly. I think about two knots, northwest, at that time there was a light fresh breeze. I could not determine its exact length, but its back protruded about twenty feet above the water’s surface, and its head, as far as I could judge, from six to eight…”

Richard Ellis, author of the book “The Search for the Giant Squid,” suggested that, in his opinion, the crew of the HMS “Plumper” encountered a giant squid. He pointed out the lack of a description of the creature’s snout and eyes, as well as the peculiar shape in the illustration from the Illustrated London News.

“Avalanche”

The Courrier d’Häiphong newspaper on March 5, 1898, described events that supposedly took place in July 1897. The French gunboat “Avalanche” was patrolling Hạ Long Bay in French Indochina at that time. Commanded by Captain Lagrésille, the unit allegedly encountered two sea serpents with small heads, about 65-foot in length and 6.5-10 feet in thickness. The crew observed that both creatures moved in the water by bending their bodies vertically (like marine mammals) rather than horizontally (like reptiles). The alleged sea serpents were about 2000 feet away from the ship, but despite the distance, the captain decided to pursue them.

He ordered the crew to shoot at the strange creatures, but the onboard marksmen missed, and the creatures disappeared beneath the water, hissing loudly and leaving a disturbance on the surface resembling a sea boil. It was not the only observation reported by the “Avalanche” crew. On February 15, 1898, in the waters of Vinh Bái Tử Long Bay, the ship supposedly encountered two sea serpents again. The captain directed the ship straight toward the creatures, and two shots were fired from a distance of 1000-1300 feet. One of the creatures dived underwater, while the other was allegedly pursued by the ship for two and a half hours.

This creature is approximately 100 feet long, has dark and smooth skin, black fins, and each emergence is preceded by a splashing stream of water caused by rapid breathing.

When it submerges, its trail can be followed due to whirlpools of water with a diameter of 13-16 feet, created by vertical undulating movements. The creature’s head resembles a seal’s head but is twice as large, and along its back, there are ridges resembling saw teeth.

On February 26, Captain Lagrésille hosted Commander Joannet and nine officers from the battleship “Bayard” on board his ship. When he told them about the extraordinary events from two weeks earlier, he was ridiculed. At the same time, the gunboat was again passing through Vinh Bái Tử Long, and the strange creatures were said to appear once more. The “Avalanche” allegedly chased the sea serpent again, this time for over 35 minutes. The officers on board, from a distance of about 655 feet, were said to watch the monster. Two of them had cameras, but they failed to prepare the equipment before the creature disappeared.

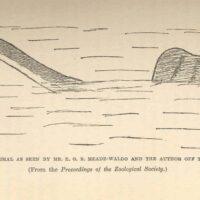

“Valhalla”

Another alleged observation took place in 1905 off the coast of Brazil. On December 7, around 10:15, the oceanographic yacht “Valhalla” supposedly encountered a strange creature. Onboard were two scientists, Michael J. Nicoll and E. G. B. Meade-Waldo, from whom the account of the encounter with the sea creature originates. According to their story, a dorsal fin about 6.5 feet long emerged from the water, rising two feet above the surface. At one point, the long neck of a large creature also surfaced. It was reportedly as thick as a human body, ending with a head resembling a turtle’s. The creature moved its neck from side to side in a very specific way. Based on this account, cryptozoologist Bernard Heuvelmans concluded that the yacht likely encountered an unidentified marine mammal.

Three days after the alleged encounter of the “Valhalla” crew with the sea serpent, the merchant ship “Happy Warrior” supposedly encountered a similar creature. Described as several times longer than the ship, the creature had a long neck and allegedly moved at a speed of about 6 knots. The “Happy Warrior” was said to encounter the monster less than 80 miles from the location where scientists from the “Valhalla” allegedly observed the creature.

Other Cases

In 1876, in the Strait of Malacca, the British steamer “Nestor” supposedly encountered a strange creature of astonishing length, about 210 feet. Three-quarters of this length were said to be the tail of the sea serpent. A similar report comes from December 30, 1947, when the passenger ship “Santa Clara” allegedly collided with an eel-like creature near the coast of North Carolina. As a result of this collision, a 50-foot creature perished. In 1969, the French-flagged merchant ship “Saint-François-Xavier” reportedly killed a large creature with a long, ringed body using its propeller. The creature had a large dorsal fin on its back.

Photographic Evidence Sea Serpent

Several alleged observers of sea serpents have managed to capture more or less distinct photos purporting to depict these creatures.

On September 12, 1964, Robert Le Serrec claimed to encounter a sea serpent resembling a giant tadpole in the shallow waters of Stonehaven Bay, located on Hook Island off the coast of the Australian state of Queensland. According to his account, he was in a small boat with his family and friend Henk de Jong when his wife spotted a dark object beneath the water’s surface. As they approached, they purportedly realized it was a large creature resembling a giant tadpole with a long, thin tail. According to the story, the creature remained motionless, possibly due to a longitudinal wound on its back.

Le Serrec had a camera and a film camera, so he took pictures of the creature. At one point, the monster allegedly started moving and swam away, bending in a manner characteristic of fish and reptiles—horizontally. Witnesses described the creature as dark-colored, with a sizable head featuring visible eyes and a wide mouth. It was estimated to be around 80 feet long. However, Le Serrec’s photos are widely considered fraudulent. Experts who examined them concluded that the placement of the creature’s eyes was anatomically impossible. The film he shot was also deemed unreliable, very blurry, and distorted.

Additionally, Le Serrec’s credibility is questionable. In 1959, he was accused of offering money to several individuals in exchange for fabricating a supposed sea serpent observation.

Other photos purportedly depict a large unknown marine creature, specifically the so-called Morgawr (Cornish for sea giant), said to appear in Falmouth Bay, Cornwall. In February 1976, the Falmouth Packet magazine received a letter signed “Mary F.,” accompanied by two photos claiming to show the alleged Morgawr. The letter described the creature as follows:

It looked like an elephant raising its trunk, but the trunk was a long neck with a small head at the end, like a snake. It had humps on its back that moved in a funny way… the creature frightened me. I wouldn’t want to get a closer look at it. I didn’t like the way it swam.

The identity of the mysterious “Mary F.” was never discovered, and the negatives of the alleged monster photos were never examined. Despite this, Janet and Colin Bord, researchers of mysterious phenomena, managed to analyze copies of the photographs, concluding that “it seems that these photos are original.”

Film Evidence

A video recording from May 31, 1982, allegedly showing a sea serpent, is another piece of evidence. The footage features a cylindrical object measuring 33-55 feet in length and approximately 12 feet in diameter. It was said to be filmed in Chesapeake Bay (bordering the states of Virginia and Maryland). In August 1982, seven scientists with various specializations, employed by the Smithsonian Institution’s complex of museums and research centers in Washington, analyzed the recording. In their summary report, George Zug from the National Museum of Natural History in Washington stated that the researchers could not identify the object, but it appeared to be animate.

Known Species

Skeptics question the authenticity of accounts of sea serpent encounters, suggesting that many alleged witnesses saw known species such as oarfish, whales (both whales and dolphins), known small sea snakes, eels, ribboned sharks, oarfish, Regalecidae fish, large cetaceans, or simply floating tree trunks, bird flocks, or giant squids.

Despite the majority of cryptozoologists acknowledging that some accounts may be observations of known animals, they point out that many descriptions do not resemble any recognized zoological creatures. However, skeptics remind us that human imagination can magnify even the most ordinary phenomena into extraordinary proportions.

Classifications

Supporters of the existence of sea serpents highlight the diversity of descriptions of alleged creatures. What skeptics consider evidence of the falsity of these stories, cryptozoologists see as evidence of the existence of at least several species of large unknown marine creatures. Several classifications of sea serpents and similar creatures have been proposed based on accounts from alleged witnesses.

Anthonid Cornelis Oudemans

In 1893, Dutch biologist Anthonid Cornelis Oudemans published the first scientific work dedicated to sea serpents—The Great Sea Serpent. In this publication, he described a creature that he gave the Latin name Megophias megophias. According to Oudemans, this creature had a long neck and tail, as well as four fin-like limbs. Only the male had a mane on its back. The scientist claimed that this species inhabited almost all the seas in the world. However, many cryptozoologists noted that Oudemans combined observations of various creatures, creating an image of an animal composed of encounters with different species.

Bernard Heuvelmans

In his 1961 book “In the Wake of the Sea Serpents,” which contains descriptions of 587 accounts of alleged sea serpent encounters (with 358 considered observations of unknown animals), Bernard Heuvelmans mentions the most famous attempt to create a typology of these creatures. He initiated this effort in 1954. Heuvelmans listed the following creatures:

- Longneck, Megalotaria longicallis – reaching approximately 65 feet in length, featuring an elongated neck and a short tail, a type of sea lion. The blubber masses of its body may resemble small humps. Heuvelmans lists 82 observations of this hypothetical creature, with 48 considered certain. Longneck has a small head, resembling that of a dog or seal in its early years, later resembling a horse, camel, or giraffe. It also has very small eyes and often peculiar growths on the nostrils. Its four limbs are fin-like, similar to those of seals.

- Sea Horse Olausa Magnus, Halshippus olai-magni – an elongated creature related to seals, with a head strongly resembling that of a horse. It also possesses a type of mane, very large eyes, and a wide mouth. Length ranging from 32 to 65 feet. There are 71 reported observations of this creature, with 37 considered certain.

- Multi-humped, Plurigibbosus novae-angliae – possibly related to whales, having a series of humps on its back. Sometimes, just behind its moderately long neck, a fin appears (Heuvelmans claimed it might depend on sexual dimorphism). The tail is equipped with a horizontal fin like that of whales. The body length is 32-65 feet. There are 59 observations, with 33 considered certain.

- Superotter, Hyperhydra egedei – a giant-sized marine otter with a highly flexible, elongated body. Approximately 65-100 feet. There are 28 observations, with 13 considered certain.

- Multifinned, Cetiscolopendra aelani – a bizarre creature with an elongated body equipped with a series of appendages resembling fins. Additionally, it seems to have a segmented body and armor or plate-like scales. It also has a short neck, a wide muzzle, and nostrils covered with fur. It moves by bending its body vertically. Length ranges from 30 to 100 feet, with an average of 65-69 feet. There are 26 observations, with 20 considered certain.

- Supereel – several species of fish: eels, lampreys, or even sharks. The elongated body gives the impression of a long neck with a small head at the end. Length varies from 30 to 100 feet. There are 23 observations, with 12 considered certain.

- Sea Crocodile – a giant crocodile or another type of reptile. Equipped with an elongated snout with teeth and a long, strong tail. Moves by bending its body horizontally, similar to other marine reptiles. Length ranges from 50 to 65 feet. There are 9 observations, with 4 considered certain.

- Yellow Belly – a giant creature shaped like a massive tadpole. Elongated and flattened body with a strong tail and a wide mouth. Brightly colored (yellow), with black vertical stripes on the sides and back. Length ranges from 65 to 100 feet. There are 9 observations, with 3 considered certain.

- Father of All Turtles – a giant-sized sea turtle. Four reports, all poorly documented.

- Great Invertebrates – a category added to Heuvelmans’ classification by other cryptozoologists.

Loren Coleman and Patrick Huyghe

The classification of sea serpents and lake monsters developed by cryptozoologists Loren Coleman and Patrick Huyghe in 2003 in the book “The Field Guide to Lake Monsters, Sea Serpents, and Other Mystery Denizens of the Deep.” It partially overlaps with Heuvelmans’ typology:

- Classic Sea Serpent – a four-legged, elongated creature. When swimming, its back bends, forming “humps.” According to the authors, it most closely resembles the extinct Basilosaurus fossil whale.

- Sea Horse – related to seals. Only males have manes, but according to Coleman and Huyghe, females have an appendage ending in nostrils. Seen in both salt and freshwater.

- Mysterious Whale – a category encompassing unknown species of whales: baleen whales with double dorsal fins, sperm whales, dolphins, etc.

- Great Shark – megalodon, a giant shark considered an extinct species.

- Mysterious Manta – a manta ray with an unprecedented pattern on its back.

- Great Sea Centipede – similar to Heuvelmans’ multifinned creature.

- Mysterious Reptile – similar to Heuvelmans’ sea crocodile.

- Turtle-Cryptid – similar to Heuvelmans’ Father of All Turtles.

- Mysterious Mermaid – most likely surviving specimens of Steller’s sea cow.

- Giant Octopus, Octopus giganteus or Otoctopus giganteus – a large-sized octopus inhabiting the tropical part of the Atlantic.