The Second French Empire, which Napoleon III (Louis Napoleon) ruled from December 2, 1852, to September 4, 1870, succeeded the brief French Second Republic. It marked a period of significant economic expansion, particularly in industry, finance, and banking, resulting in social changes such as the growth of the working class. After an authoritarian phase characterized by the repression of opposition, a degree of liberalization within the regime emerged.

Despite several military and diplomatic successes (Crimean War, Italian Campaigns), the failure of the Mexican Expedition and, notably, the military defeat against Prussia in 1870 led to the downfall of the Second Empire.

Napoleon III: Prince-President of the French Second Republic

On November 4, 1848, the fledgling French Second Republic adopted a new constitution after lengthy negotiations. This constitution vested executive power in a president elected by universal suffrage and legislative power in the National Assembly. Presidential elections were set for December 10 and 11, 1848.

These elections aligned perfectly with the political ambitions of Prince Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, the nephew of the emperor, who sought a return to politics on this occasion.

Republican votes were divided among the candidacies of General Cavaignac (representing the moderate Republicans), Ledru-Rollin (the most hardline Republicans), Raspail (the revolutionary socialists), and Lamartine, who had lost all his popularity.

The popular current, represented by the more conservative candidates, rallied behind Louis Napoleon Bonaparte. The prince’s carefully crafted election program included amnesty for all political convicts, reduced taxes and military conscription, an ambitious public works policy to address unemployment, social welfare measures, and modifications to industrial legislation.

On December 20, 1848, Prince Louis Napoleon Bonaparte was elected with nearly three-quarters of the votes. He garnered support from peasants, a portion of the working class, and the Party of Order, whose influential members would hold key ministerial positions. Quickly, the president’s mandate veered towards an authoritarian regime, temporarily quashing the aspirations of the Republicans.

Birth of the Second French Empire

In 1851, faced with the impossibility of obtaining a constitutional revision allowing his reelection, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte orchestrated a coup d’état on the symbolic date of December 2nd. A skilled tactician, he positioned himself as a recourse in a deliberately darkened context, relied on the judgment of the people (universal suffrage), and placed his actions under dual symbolic patronage (the French Revolution and Napoleon I).

However, while an overwhelming majority of the French people approved of the new political regime and the prospect of a return to expansion in peace, the traumatizing anti-republican repression fueled lasting animosity toward him and prevented the complete success of his plebiscitary strategy.

The year 1852 marked a period of dictatorship in the Roman sense. With the social peril averted and the futile games of the parties interrupted, institutions aimed at restoring the country’s stability were hastily established. Essentially borrowing from the provisions of the Constitution of the Year VIII, the new constitution was ready on January 14, 1852, and pre-approved by the plebiscite on December 21.

The president, a “responsible leader” before the people, was chosen for ten years. He governed “by means” of ministers who depended solely on him and a Council of State composed of the “most distinguished” 50 individuals who shaped his draft laws and defended them against a Legislative Body (Corps législatif) that lost its designation as the National Assembly.

Only the president, who had the support of 8 million French citizens, could claim to represent the people; the Legislative Body consisted of 260 to 290 “deputies” and was no longer a representative body. It convened only three months a year to approve or amend bills; at least, it voted on the budget, but as a whole, it was without control over expenditure allocations, rendering its power negligible. The Senate, “formed of all the illustrious figures of the country,” held more prominence. It judged the constitutionality of laws and was the sole interpreter of the Constitution, subject to modification by a Sénatus-consult.

After a “journey of inquiry” across the country, where public opinion was shrewdly influenced by prefects, it was through the Sénatus-consult of November 7, ratified by a plebiscite on the 31st with 7,824,189 yes votes against 253,145 no votes, that the prince-president became the “Emperor of the French.” Napoleon III was crowned on December 2, the anniversary of his uncle’s coronation, the victory at Austerlitz, and the coup d’état of 1851.

Authoritarian Empire

With the assistance of a growing army of officials, which rose from 120,000 in 1851 to 265,000 by the end of the Empire, effective prefects with increased powers enforced the emperor’s will in the provinces. This period marks a significant step in France’s path towards centralization. The public was willingly prepared to follow. The prefects are responsible for appointing mayors, deputy mayors, and teachers.

In the legislative body elected on February 29, 1852, out of 261 deputies, only 8 were opposition members, including 3 Republicans who refused to take their seats to avoid swearing allegiance to the Constitution. Prefects manipulate the system of “official candidacy,” securing 5,600,000 votes for government candidates despite a 37% abstention rate.

In the 1857 elections, only 12 opponents out of 267 deputies, mainly Republicans, the Les Cinq (the Five), including Émile Ollivier, participated this time. The imperialists consistently garnered 5.5 million votes. Should we not acknowledge that such majorities cannot be entirely “manufactured” and that the authoritarian empire is indeed a popular regime? Perhaps the answer lies in “middle ground.” France was both anesthetized and captivated.

However, it becomes evident that the regime was reactionary, both politically and socially. The repression since December, extending to the General Security Law, a true “Law of Suspects,” in February 1858, primarily targeted the left—workers, republicans, and common people in both urban and rural areas, much to the satisfaction of the Order.

Since the 1851 French coup d’état, the Empire has acquired a “reactionary bent.” Despite the efforts of figures like Morny, president of the legislative body until 1865, or Persigny, interior minister until 1854, there has been no renewal of the political class, genuine Bonapartists are rare, and there was no “imperialist” party. The overwhelming majority in the legislative body was mostly composed of members from the former Order party, who, fearing “anarchy,” temporarily forgot that they were also “liberals.”

The Empire maintains and expands the arsenal of repressive laws from its predecessors, particularly in press matters. As the then-prince president of Bordeaux stated in 1852, it primarily depends on the Catholic Church. Congregations multiply; their numbers go from 4,000 religious in 1851 to 18,000 a decade later. They take control of primary and secondary education. The entire lower clergy and the majority of bishops aligned themselves with the Empire.

Napoleonic Ideas

Napoleon III does not, by any means, wish to be seen as a champion advocating for the restoration of order. Although he opposes the Reds, he does not align himself with the Whites. His aspiration is to be associated with the blue, his favorite phrase being ‘I belong to the Revolution.’ The preamble of the 1852 Constitution states that it “recognizes, confirms, and guarantees the great principles proclaimed, which form the basis of the French public power.” The emperor, a man of progress and a son of ’89, holds what an 1839 book titled “Napoleonic Ideas”

‘Abroad, national dignity!’ was the first of these ideas that he implemented. He had indeed promised that the Empire would bring about peace. However, it was necessary to engage in the bellicose game of Europe to erase the shame of the treaties of 1815. England stood by France’s side in 1854–1855 during the victorious Crimean War, undertaken to halt the Russian threat to the Turkish straits connecting the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. Prussia and Austria remained neutral, and the old coalition of 1815 was finally broken. At the Paris Congress of February 1856, France, appearing as a mediator, regained the place that suited her in the world.

A Europe committed to progress must uphold the principle of nationality and the right of peoples to self-determination. In 1859, alongside the small Piedmont, there was a victorious yet costly war against Austria to achieve the unity of Italy. Italy emerged nearly united, with only Venetia remaining under Austrian control, and notably, Rome was retained by the Pope. France acquired Nice and Savoy. This French pursuit of greatness is further evident in the global expansion from 1859 to 1867, encompassing the conquest of Cochinchina, the establishment of a protectorate over Cambodia, and the definitive presence in Senegal.

When the time came, a decree on November 24, 1860, restored the right of address to the Legislative Body. In 1861, the right to examine the budget in detail, by sections, was also reinstated. The Napoleonic idea extended to the ‘well-being of the people,’ declaring that ‘the reign of castes is over.’ Workers, whom the Empire sought to appease, gained the right to strike in 1864, marking a crucial conquest.

To ensure economic prosperity that generates well-being for all, free-trade treaties were signed with England in 1860 and, in the subsequent years, with other European countries.

—>Napoleon III’s military interventions played a role in Italian Unification. The French-aided Austrian defeat in 1859 helped pave the way for the unification of several Italian states.

Reign of Business

The Empire, in economic matters, demonstrated a decidedly modern approach. It was not yet a matter of state intervention, but progress was inspired and sometimes facilitated through direct assistance. The years 1852–1870 marked a privileged period of agricultural prosperity, driven by a favorable trend in global prices. Activities focused on territory development, land reclamation, the expansion of local roads, increased use of fertilizers, and the initiation of agricultural credit.

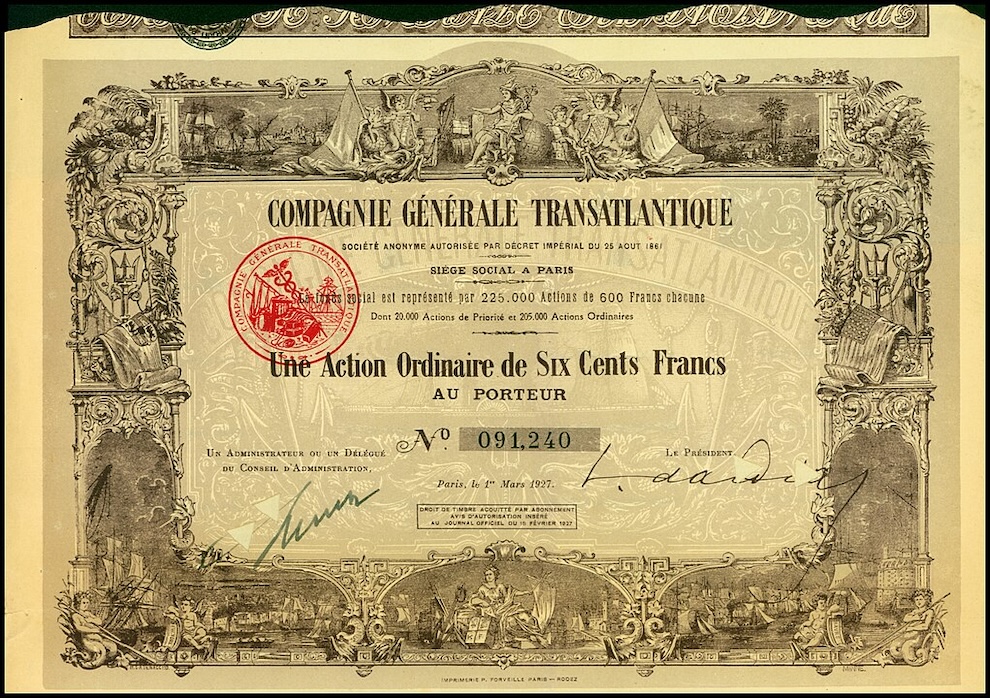

A revolution unfolded in the banking world. The sturdy yet cautious network of the “high” or “old” bank had long dominated all financial activities. A decree issued on November 18, 1852, authorized the establishment of the Crédit Mobilier by the Pereire brothers, aiming to become the prominent national investment bank envisioned by Saint-Simonian industrialists. The Crédit Mobilier played a decisive role in railroad ventures, both in France and abroad, including Spain and Austria, as well as in urban planning projects in Marseille and Paris. Additionally, it contributed to maritime navigation, exemplified by its involvement in establishing the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique.

Having played a high-stakes game and faced opposition from traditional banks, notably the Rothschilds, the Pereire brothers had to withdraw in 1867.

Less venturesome, major financial institutions emerge, mobilizing private deposits to capitalize on industry and business. They formed the framework of the future modern banking network: in 1863, Crédit Lyonnais; in 1864, Société Générale; and the Bank of the Netherlands, the precursor to Paribas.

A decisive revolution in communication also took place. By 1870, the French railway network, spanning 17,000 km, had been largely completed, providing a significant impetus to the development of heavy industries. These industries experienced a growth rate of over 6% per year, undergoing modernization and consolidation to confront English competition.

Notably, cities such as Paris, Lyon, Marseille, and Bordeaux underwent reconstruction and expansion, reflecting the adage, “When construction is booming, everything is thriving.” The Empire marked an era of financial dominance, as highlighted by a publicist in 1863, who stated, “Banks, steamships, railways, large factories, and companies of any kind, forming a capital of shares and bonds of 20 billion, were in the hands of 183 financiers.” However, despite being inadequately explained, a “slowdown” in growth initiated around 1860–1865, persisting until the end of the century.

The Metamorphosis of Paris Under the Second French Empire

Paris in the first half of the 19th century was a city in decline. Infrastructure, housing, roads, sewers, and hospitals had not kept pace with the significant population growth: within the boundaries of old Paris, 600,000 inhabitants lived in 1801, 817,000 in 1817, and 1,152,000 in 1856. In central neighborhoods, population densities frequently exceeded 1,000 inhabitants per hectare. The cholera outbreak claimed 18,400 lives in 1832 and 16,000 in 1849.

In 1853, Maxime du Camp stated that “Paris was becoming uninhabitable” at the time when Baron Haussmann was appointed prefect of the Seine. Fulfilling the emperor’s directive, Haussmann initiated an extensive project of redevelopment and beautification, entailing the demolition and reconstruction of entire districts. The Haussmannian avenues, broad and straight, adorned with tree-planted sidewalks and buildings featuring elegant facades, introduced a sense of openness to the urban fabric. Simultaneously, the transportation network underwent a profound overhaul.

A grand cross-section traversed Paris, extending from north to south through the boulevards of Strasbourg, Sébastopol, and Saint-Michel, and from west to east along the streets of Rivoli and Saint-Antoine. The expanded Place du Château-d’Eau (République) saw the extension of boulevards Magenta and Voltaire, along with the rue de Turbigo, aimed at facilitating access to vibrant working-class neighborhoods. Towards the west, expansive avenues radiated from the Étoile; to the north, Boulevard Haussmann and Rue La Fayette were crossed; and to the southeast, Boulevard Saint-Germain was developed.

The Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes were developed. The sewer system expanded from 200 to 600 kilometers; water was sourced from the Marne and the Dhuys. The operation incurred a considerable cost of $2.5 billion. Left to private enterprise, construction led to rampant speculation. The affluent districts were embellished far more than the popular districts. However, with the annexation of its suburbs in 1860, Paris could accommodate nearly 2 million inhabitants in its 20 arrondissements within these 60,000 houses.

—>Haussmannization refers to the urban planning and renovation carried out in Paris by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann under Napoleon III. It involved the creation of wide avenues, parks, and modern infrastructure, transforming the city’s appearance.

Rising Threats

The second decade of the reign reveals signs of wear and even cracks. In the 1863 elections, the opposition—diverse, ranging from liberal monarchists to republicans—secured 2 million votes, with about thirty elected representatives. Silenced since 1852, the political class regained momentum. On January 11, 1864, Thiers made a resounding return to the Legislative Corps, demanding “necessary” individual freedoms, freedom of the press, freedom of opinion, and, above all, parliamentary freedom.

A warning shot! Some deputies are poised to coalesce around this program, forming a ‘third party”—a play on words for Thiers’ party. Simultaneously, the Empire encountered significant setbacks in foreign policy: challenges in Italy, where the populace clamored for Rome as the capital; the collapse of a bold expedition to Mexico; and the inexorable advancement of German unity centered around Prussia.

Political concessions were necessary; in 1867, the right of interpellation was restored to deputies; in 1868, a law significantly relaxed the press regime, and another law authorized public meetings during electoral periods. “Public opinion” can now express itself.

Radically contesting the regime’s existence, the Republican Party launched a vigorous offensive on the public stage. Led by a new generation of activists like Gambetta and Ferry, it particularly advanced in urban areas. However, the working class refused to respond to the advances of the “emperor of the workers.”

Social tensions intensified with an increasing number of strikes and the proliferation of workers’ trade unions, most of which joined the International Workers’ Association with the motto, “The emancipation of workers will be the work of the workers themselves.” Indeed, they placed their hopes in an imminent revolution to establish a democratic and social republic.

—>The French intervention in Mexico (1861–1867) was a military campaign by France, led by Napoleon III, aimed at establishing a French-friendly regime in Mexico. It resulted in the short-lived establishment of the Second Mexican Empire under Maximilian I.

The Liberal Empire: End or Beginning Again?

In the 1869 elections, government-backed candidates received only 4.4 million votes, while the opposition, encompassing all tendencies, secured 3.3 million. A majority, consisting of moderate opposition and liberal government members, now emerges in the Legislative Corps, demanding a return to a parliamentary regime. This transition becomes imperative.

Through two Sénatus-consulte decrees on September 8, 1869, and April 20, 1870, the powers of both chambers were expanded, establishing ministerial responsibility. The liberal third party emerged victorious, although without Thiers, who was considered too formidable of an adversary. On January 2, 1870, the emperor assigned the task of forming a ministry that would ‘be homogeneous and faithfully represent the majority of the Legislative Corps’ to Émile Ollivier, a repentant republican.

Advocates propose a return to the parliamentary regime that had pleased the bourgeois political class since 1830. Does this signal the end of the Empire? “Patching up” doesn’t seem unfavorable; could a parliamentary empire not be viable? Did the emperor not promise to restore freedom, the “crowning achievement” of the system, when the time came? Indeed, Napoleon III skillfully rebalances the situation in his favor.

On May 8, 1870, he requested the nation’s approval for the significant reforms he had just undertaken through a plebiscite. Universal suffrage overwhelmingly supported the reforms, with 7.3 million yes votes and 1.5 million no votes, affirming that the emperor’s popularity remained intact, if not strengthened. While the executive was no longer entirely sovereign, it retained both its aura and prerogative. Despite deep disappointment, the Republicans realized that converting the country would require at least another generation of propaganda, education, and efforts.

Legacy of the Second French Empire

And it is not, in fact, from this crisis, ultimately well overcome, that the Empire dies. It found, as it were, a second wind when, imprudently—”with a light heart,” says Émile Ollivier—on July 19, it engaged in the 1870 war against Prussia, which was becoming decidedly too arrogant at our Rhine border. Victory would have been easy, further consolidating the regime.

However, the Prussians breach the borders of Alsace immediately; the bulk of the army, with Bazaine, becomes trapped in Metz. A relief army, led by Mac-Mahon and the emperor himself, faces a cruel defeat at Sedan on September 1, resulting in Napoleon III becoming a prisoner. Upon receiving the news in Paris, a provisional government of the Republic was established, marking the end of the Second Empire.

Despised by republican historiography, which one might argue is biased, the Second Empire appears as a hybrid regime. Simultaneously a reissue of the first and not, it maintains its democratic essence: the Constitution replicates the terms of that of the Year VIII and reaffirms and safeguards the fundamental principles of 1789. Most notably, universal suffrage is upheld, marking a lasting acquisition of a right that can no longer be revoked.

Its popularity, spanning almost twenty years, serves as a guarantee. Initially authoritarian, it eventually underwent a process of liberalization. While it began as such, it was never truly totalitarian. The country inherits from this empire an original tradition that doesn’t align strictly with either the right or the left—a trend that sporadically resurfaces in French political life.