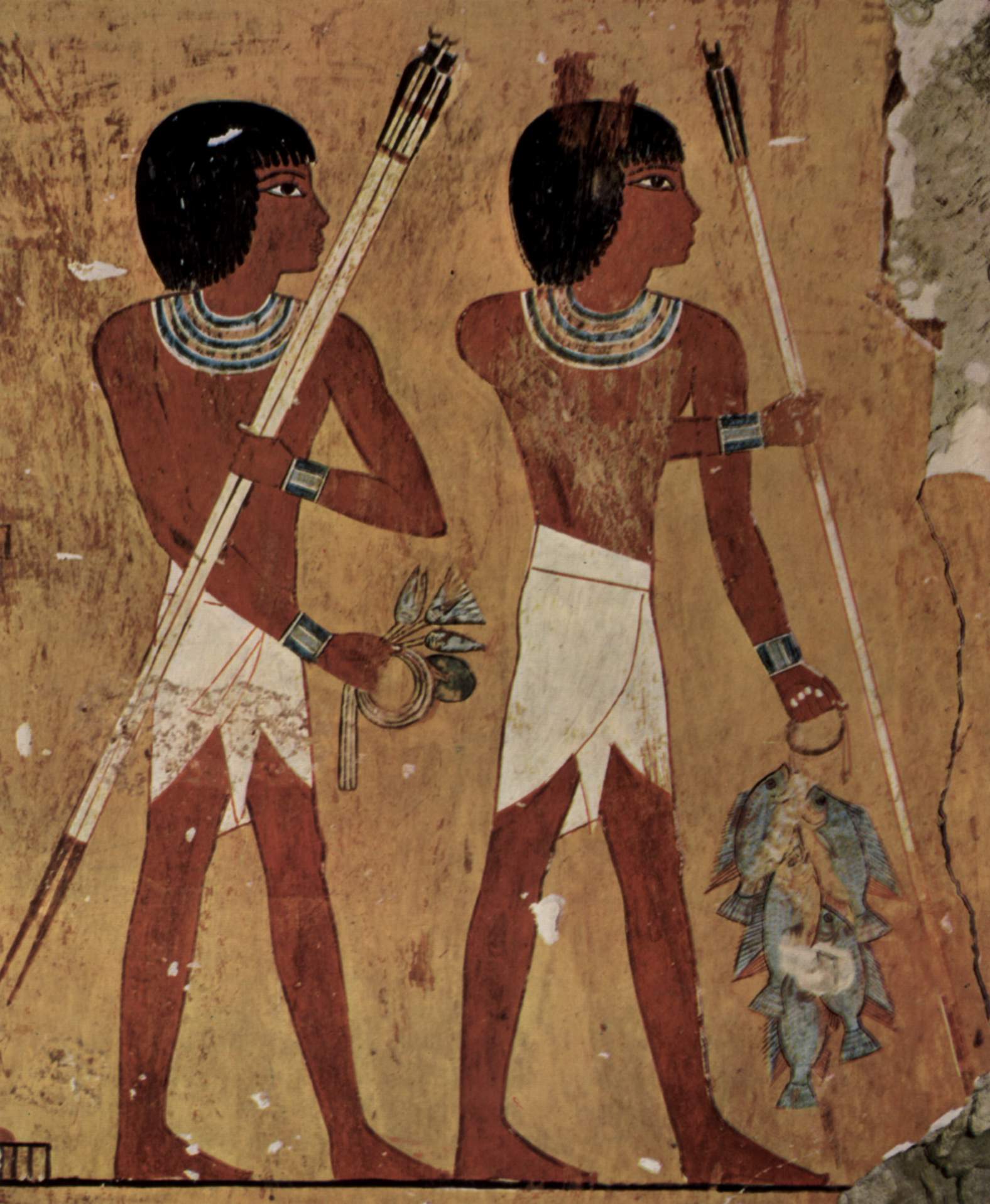

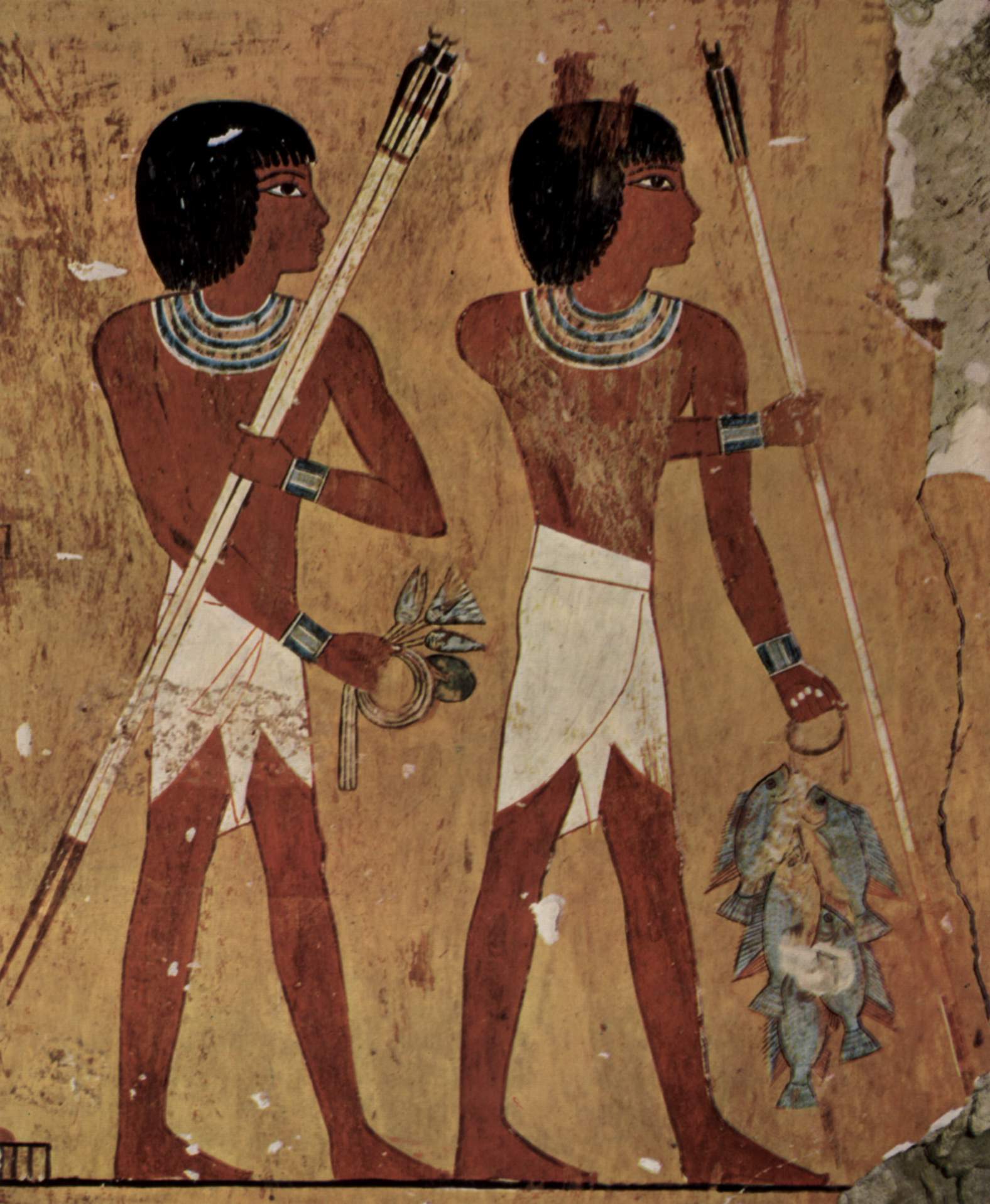

Shendyt: The Traditional Short Skirt of Ancient Egyptians

Shendyt was a male garment in the form of a short skirt that was worn by the ancient Egyptians, at least since the Old Kingdom.

Shendyt was a male garment in the form of a short skirt that was worn by the ancient Egyptians, at least since the Old Kingdom.