The sources of Greek thought comprise a combination of political, social, economic, and cultural factors present during the archaic period of Greek history, leading to the transformation of religion, beliefs of wisdom and morality, and practical-technical knowledge into science and philosophy.

Novelty of Ancient Greek Thought

Jean-Pierre Vernant points out a complex of three characteristics defining the novelty of Greek thought compared to Eastern thought:

- Establishment of thought providing an independent explanation of the world, separate from mythology and religion – explaining the existence of the cosmos and the course of natural phenomena independently of theological-poetic concepts, as found, for example, in the works of Hesiod.

- Introduction of the idea of a prevailing autonomous order in the world – the cosmic order is not theocratic but is based on the principle of immanent law (nomos), imposing the same character on all natural phenomena (kratos).

- Geometrical character of thought – geography, astronomy, and cosmology describe the world within a defined space and constructed upon relationships occurring solely among its elements (reciprocal, reversible, and symmetrical).

The concept of the sources of Greek thought is significant not only for the history of ancient philosophy but also for the historical methodology of science, philosophy of culture, and cultural anthropology, which examine the relations between myth and logos, primitive thinking and rational thinking, and various philosophical currents, especially Hegelianism, Martin Heidegger’s philosophy, in which categories of origination and rootedness arising from the interpretation of the beginning of Greek philosophy became the principal philosophical categories, for the thought of German physicist-philosophers like Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker or Werner Heisenberg, and also for Marxist historiography, which sees (partly due to Lenin’s recognition of the “Democritean trend of philosophy”) in the origins of Greek philosophy a break with religion and primal materialism.

Origin of Ancient Greek Thought

The original character of Greek thought

For centuries, the origin of philosophical thought in Greece was a subject of dispute – there was debate about whether it originated from the East or if it was an original product of Greek culture. The belief in the eastern origin of philosophy arose already in antiquity. Diogenes Laertius (3rd century CE) in the prologue to the “Lives and Opinions of Famous Philosophers” presents this argument along with its criticism:

“Some say that philosophy originated among the barbarians. As proof of this, they adduce the Chaldeans, the Magi, the Gymnosophists of India, the druids among the Celts and Galatians, and the Sramanas among the Bactrians. Mochus, they say, was a Phoenician; Zamolxis, a Thracian; Atlas, a Libyan.”

However, those who assert this do not realize that they are ascribing to the barbarians what belongs in reality to the Greeks, nor do they see that they are declaring that philosophy has its beginnings among the non-Greeks. Musaeus was an Athenian, and Linus was a Theban. Philosophy therefore dates from the Greeks and is not, as they maintain, a matter of barbarian origin.

[Diogenes Laertius, I 1-4]

Until the 19th century, the prevailing theory was that philosophy originated from a lost and esoteric knowledge of Egyptians and Babylonians and from the Holy Scripture, especially from the activities attributed to the author of the Pentateuch, Moses. This view changed only with a deeper understanding of the civilizations of the Near East through archaeological discoveries and the deciphering of hieroglyphic and cuneiform scripts. Currently, while acknowledging that knowledge of the East was a necessary condition for the emergence of philosophy in Greece, the most widespread view is that neither philosophy nor science understood as theoretical knowledge existed in the civilizations of the Near East. This view, entrenched in the 18th and 19th centuries, was later subject to criticism. Initially, Western philosophy began to be contrasted with Eastern philosophies, and in recent decades terms such as Egyptian philosophy, Mayan philosophy, or African philosophy have also been used, which reflects a departure from Eurocentrism but also an expansion of the meaning of the term “philosophy.”

The culture of Eastern peoples is much older than that of the Greeks, yet it is difficult to find in it propositions about the world and humanity that do not have a mythological and religious character. Therefore, in research on the sources of Greek philosophy, Aristotle’s thesis about the transition from mythos to logos is popular. The peoples of the Near East had art and practical skills approaching science (especially geometry in Egypt and astronomy in Mesopotamia), developed religious systems, and enacted legislation. In all these areas of life, Greek culture is closely dependent on them. However, the transition from mythos to logos does not have a quantitative but rather a qualitative character of a leap (“Greek miracle”). In the philosophy of history, the thesis is advanced that it was precisely this enormous change, the emergence of philosophy in Greece, that determined the distinctiveness of Greco-Roman civilization from the civilizations of the Near East and became the cause of the divergence of their developmental paths.

Theses on the foreign origin of Greek thought

Since ancient times, the thesis of the eastern origin of Greek philosophy has been widely accepted. In the 19th century, it was particularly popular among historians of Romanticism, in line with the general characteristics of this cultural movement, which rejected many values produced by classical culture in favor of folk, oriental, or specifically understood medieval cultures, as well as among orientalists. This happened despite the fact that the thesis of the foreign origin of Greek philosophy was alien to the dominant Hegelian historiography of that period. Hegel regarded Indian philosophy coolly, considering it identical to Indian religion. Today, despite significant progress in the study of Far Eastern philosophies, the independence of Greek philosophy from religion is also recognized as one of the most important factors that enabled its emergence.

According to Hegel, in Indian philosophy, philosophical concepts exist, but Spirit in the civilizations of the Far East has not yet taken the form of thought, and philosophy present there is only of a symbolic character; it also lacks the characteristic theoretical character found in Greek thought, but only has a practical-ethical element with a religious background, such as enlightenment and liberation. It was only in the second half of the 19th century that a thorough analysis of the development of Greek thought was conducted, presenting an extensive corpus of arguments against the eastern origin of philosophy. Particularly significant here are the historical analyses of Eduard Zeller in “Die Philosophie der Griechen in ihrer geschichtlichen Entwicklung” (1919), which systematized a vast source material, and John Burnet’s “Early Greek Philosophy” (1930).

The key significance of rejecting the thesis of the eastern origin of Greek philosophy is that it appeared late in antiquity, was mainly promoted by people from the East, and was largely within philosophical currents of an esoteric nature, seeking to give themselves the splendor of antiquity, such as Neopythagoreanism and Neoplatonism. The intentions of the creators of these mystical philosophical currents can be described as “local patriotism.” In the Hellenistic period, unlike in the Archaic period, Greeks regarded Eastern peoples as barbarians, leading to cultural friction. At the same time, Eastern peoples conquered by the Greeks quickly adopted Greek culture, combined with their own religious-theological concepts, creating syntheses of an esoteric nature.

It should also be noted that in Greek culture, philosophy was considered the highest form of knowledge; therefore, if religiously oriented thought of late antiquity wanted to reject Homeric Greek religion and turn to Eastern cults, such as the cult of Isis and Mithras, it had to simultaneously acknowledge that the highest form of knowledge, philosophy, ex origine, was contained in these cults.

Egyptian priests in the Ptolemaic state were known for maintaining that all Greek knowledge stemmed from ancient Egyptian wisdom; they motivated this claim (now considered hypothetical) with the journeys of Plato, Pythagoras, or Thales to Egypt, from where they were said to have brought knowledge and philosophy to Greece. The idea of the origin of philosophy from Moses and the Old Testament prophets was also strongly rooted among heavily Hellenized Alexandrian Jews, who also produced their own mystical philosophy, the most distinguished representative of which is Philo of Alexandria. With the development of the religious character of culture in the last centuries of antiquity and the penetration of Eastern cults into all regions of the Roman Empire, such theses became widely known and accepted among Greeks and Romans, especially among Neoplatonists, who proclaimed that philosophy comes from divine inspiration.

Romantic researchers believed that they could prove the thesis of the eastern origin of Greek philosophy simply by accepting the statements about it made by ancient philosophers as credible without subjecting them to source criticism. Especially German researchers of that period tried to create syntheses of Eastern and Western thought and sought strict, orderly, and systematic analogies in them. An example of this is the work of August Gladisch, “Religion and philosophy in their world-historical development and relation to each other according to the documents” (1852), in which Gladisch, based on internal convergences, distinguished five philosophical systems that combine genetically and thematically Western and Eastern trends: the Pythagorean-Chinese system, the Eleatic-Indian system, the Heraclitean-Persian system, the Empedoclean-Egyptian system, and the Anaxagorean-Jewish system. The current state of knowledge about this period necessitates rejecting these theses.

Neither philosopher nor historian of the classical period mentions the origin of philosophy from the East—not even Plato, who discusses topics related to the East, or Herodotus, who traces Orphism back to Egypt, well acquainted with and treating the East with understanding, express such an opinion. Plato emphasized the speculative and theoretical orientation of Greek thought, distinguishing it from the practically-oriented Egyptian knowledge. Aristotle diminished the significance of Egyptian achievements, attributing to them only the invention of mathematics.

Other arguments against the origin of Greek philosophy from the East include the fact that the idea of the eastern origin of philosophy found recognition in the Greco-Roman world in the late period of ancient philosophy, when revelation gained greater importance than reason; that late Greek philosophy took on a mystical-religious character, which could find real similarities between its doctrines and Eastern religions, although these similarities do not speak to their relationship to original Greek philosophy, but rather to changes occurring within it; and that Egyptians and Jews saw similarities between Greek philosophy and their religion based on interpretations that were obviously arbitrary, interpretations of an allegorical nature. Another argument against the origin of philosophy in the Middle East is that no philosophical writings or a distinct system of teaching and transmitting philosophy different from existing writings and systems of teaching religion, cosmogony, and theology emerged there, nor was there any term that could be recognized as equivalent to the term “philosophy.”.

Vernant admits that in his research he did not adequately present the issue of the influence of Eastern mathematics on the emergence of Greek science, but he claims that the process of the development of mathematical thought in Greece can be presented as a component of his conception of its emergence as a change in the social function of speech. However, there are contemporary concepts that try to derive Greek civilization from outside Greece based precisely on the foreign origin of mathematics. The Dutch mathematician Bartel Leendert van der Waerden, in his work “Geometry and Algebra in Ancient Civilizations,” claims that the foreign origin of mathematics can be understood as a “triple discovery.”.

Its first element is the research of Abraham Seidenberg concerning the construction of altars in Indian texts from the V–II century BC and the presence of mathematics and Pythagorean triangles in them, from which Seidenberg deduces the thesis of the common origin of Greek, Babylonian, and Indian mathematics. The second consists of comparative studies of Chinese arithmetic texts and Babylonian texts; they turned out to be so similar that hypotheses about their common source were put forward. The third consists of the research of Alexander Thoma and Archibald Stevenson Thoma on megalithic constructions in England and Scotland and the functions that mathematics and Pythagorean triangles fulfilled in them. Based on these three sources, van der Waerden concludes that mathematical knowledge originated in Neolithic Central Europe, from where it only later spread to Western Europe and Asia.

Religion and Mythology in the Origins of Philosophy

Homer and Hesiod

The works of Homer and Hesiod played a tremendous role in Greek culture, including the emergence of philosophy.

In Homer’s works, gods directly intervene in events occurring in nature, in the human world, and in the psyche. There is also the concept of impersonal necessity standing above the gods. Homer also attempts to present the relationships between the gods and their functions in a systematic way, which is the beginning of understanding cosmology as order.

Hesiod, in his “Theogony,” described the creation of heaven and earth and the stages of the development of reality as a change in the generations of gods. The tendency to explain natural and human reality as a certain order comprehensible to reason is even more pronounced than in Homer.

Philosophers continued these attempts to grasp the world as a whole, ordered according to some governing principle (Arché), but in a fundamentally different way, detached from mythology and religiosity.

Religion

Formerly, the materialism of early Greek philosophy was strongly emphasized; currently, much greater emphasis is placed on the fluid transition from mythology to philosophy, as well as the present theological and ethical factors in both early and mature Greek philosophy. According to Kazimierz Leśniak, who sees pre-Socratic philosophy as materialistic, “Greek philosophy emerged when it was realized that beneath the apparent chaos of phenomena must lie order, and that this order is the work of self-originating forces, not associated with any deity.” Vernant also recognized the break with the mythological explanation of the world as the fundamental cause of Greek philosophy, while emphasizing the fluidity of this transition, which Leśniak also emphasizes.

Ionian philosophy can be obscure; this obscurity stems not only from its metaphorical or gnomic form and the scant amount of preserved fragments but also from the fact that the transition from the resistant-to-rational-analysis, symbolic categories of mythological speculation to rational philosophy is fluid in it. According to Leśniak, it is not possible to delineate the line between what is mystical, irrational, and anthropomorphic and what is scientific and philosophical among the Ionians. Irrational and mythological elements also appeared in later Greek philosophy; however, they are easier to separate from the proper part of their views in Plato and Aristotle. Furthermore, later Greek philosophers were clearly aware of the distinction between mythology and philosophy; they were aware of it so clearly that they could even use myths consciously and intentionally, especially Plato.

It is not always possible to indicate what exactly in Ionian philosophy is rational and what is mythological. A widespread, though difficult to prove, view is the connection between the animistic origin of hylozoism and the view of Ionian philosophers that the entire reality is animate. This view may have originated in animism, but it could just as well be based on inferences from simple empirical observations. The difficulty of separating the rational element from the mythological one also stems from changes in scientific views and the ambiguity of the term “rationality” itself.

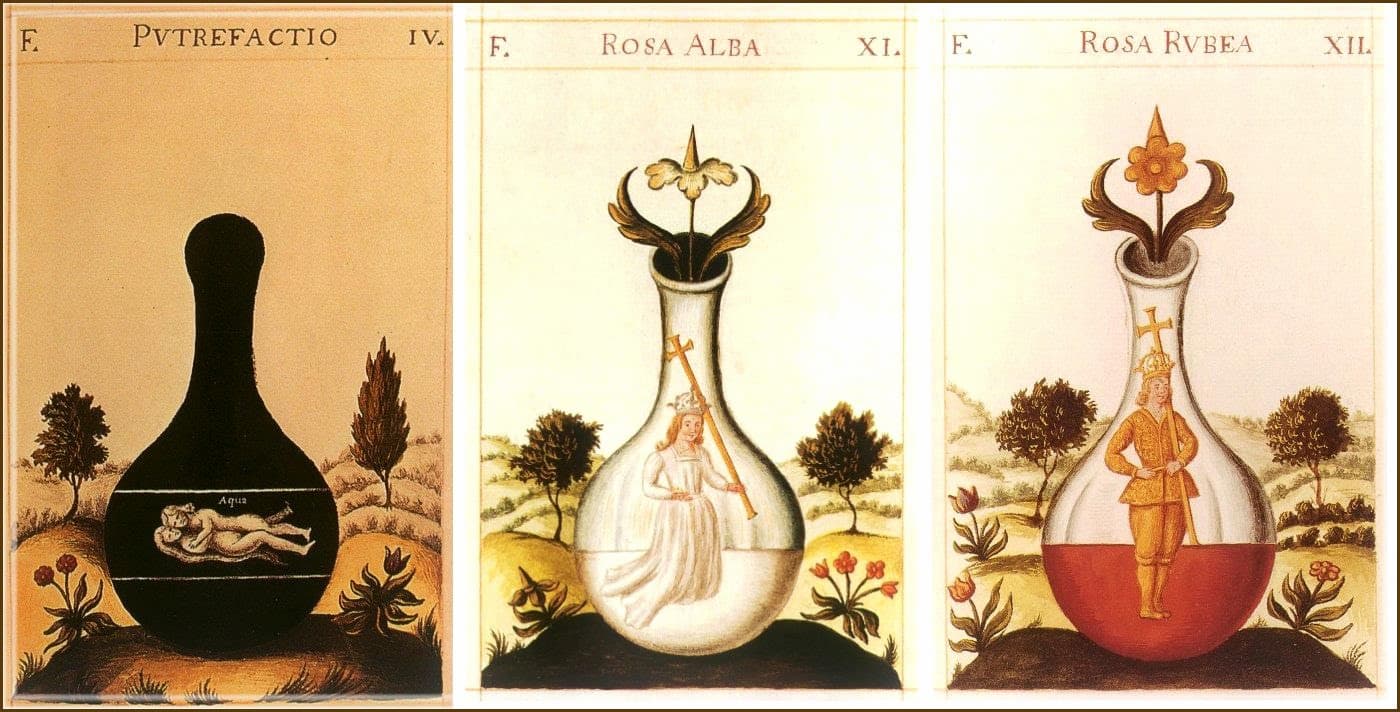

Orphism

Orphism was a mystery religion focused on deepened and more authentic spirituality. It was popular among those Greeks for whom superficial ritualism of official religion was not enough. Part of the religion was secret teachings transmitted to adherents, according to which a divine principle, an immortal daemon, inhabits humans. He fell into the material world due to guilt and became trapped there. With the death of the body, the daemon does not die but is reborn. Orphism allowed for purification, breaking the cycle of reincarnation, and releasing the daemon into the afterlife. Many Orphic teachings about the soul and its journey, the non-material perfect sphere of reality, and forms of initiation into secret knowledge would be adopted by later philosophers.

The Beginnings of Philosophizing

Activity of Greek sages and lawmakers

One of the main sources of Greek philosophy, especially Greek ethics, is the wisdom conveyed in the form of practical life rules. During the archaic period, the Greeks collected many such rules, mostly in the form of aphorisms, proverbs, and gnomes – they were important for the daily life and morality of the Greeks even after the emergence of philosophical ethics. These rules arose in response to the turmoil caused by rapid changes in Greek society in the 7th and 6th centuries BC. They were expressed by sages, individuals with particularly high respect in local communities, who had a significant influence on their lives. Greek sages were often lawmakers, social reformers, and tyrants. Due to their great importance for the life of the poleis in the archaic epoch of the 7th and 6th centuries BC, this period is sometimes called the “era of the seven sages”.

Ionian philosophy of nature

The main feature of the Ionian philosophy of nature was its attempt to formulate a theory of the world in a simple and concrete way—to answer questions about its origin, structure, and mode of operation. This characteristic was associated with the practical attitude emphasized by many authors of Ionian philosophers. This practical attitude does not negate the revolution represented by the establishment of the rudiments of theoretical knowledge by Ionian philosophers; on the contrary, theoretical knowledge arose precisely from the need for better satisfaction of practice.

Writes about Ionian philosophers: “They were not hermits immersed in inquiries into detached issues or observers of nature but active, practical people, whose philosophy had this novelty in that when they began to contemplate the mechanism of reality, they did so in the light of everyday experiences, not entirely disregarding ancient myths. They owed their independence from mythological explanations more to the fact that the relatively simple political structure of their growing states did not force them to rule by superstition, as was the case in previously existing states.” Farrington confirms Vernant’s view on the great importance of changes in political relations towards the Mycenaean era and the diversity of Greek political relations towards Asian relations as a reason for the independence of Greek thought from mythological explanations. Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes did not differ in political life from the sages; they actively participated in their lives, carried out reforms, and directed colonization, law, and economy.

Origin of the term “philosophy”

The term “philosophy” probably did not appear in the Greek world before the 5th century BC; hence, defining the philosophical self-awareness of early natural philosophers is difficult. Pierre Hadot even uses the term “philosophy before philosophy” in relation to the first philosophers of Greece. The first certain, yet quite incidental, uses of the word “philosophy” date back to the 5th century BC, and it was only Plato who philosophically defined the concept of philosophy.

Hadot denies the old anecdotal tradition according to which the word “philosophy” was known to Pythagoras and Heraclitus. There is a legend passed down by Heraclides of Pontus, Diogenes Laertius, Cicero, and Iamblichus that Pythagoras was the creator of this term. Diogenes Laertius writes:

The term “philosophy” was first used by Pythagoras, and he was also the first to call himself a philosopher, namely in Sybaris, in conversation with Leon, the ruler of Sybaris or Croton. Then, as stated by Heraclides of Pontus in his work On the Dead, Pythagoras said that no man is wise; only God is wise. Before, philosophy was called wisdom, and a person practicing philosophy and already perfecting it was called a sage, whereas a philosopher was one who loved wisdom. Sages [or philosophers] were also called sophists, not only them but also poets; for example, when Cratinus praises Homer and Hesiod in Archilochus, he also speaks of them as sophists.

The issue of the presence of the adjective philosophos, the verb philosophize, and the noun philosophy in Pythagoras and Heraclitus remains disputed. The fragment of Heraclitus in which the word “philosopher” appears is considered inauthentic, and the fragment concerning this word in Pythagoras is considered a mistaken, anachronistic interpretation, as a result of which Plato’s position was attributed to this philosopher.