The Talisman of Charlemagne is a 2.9-inch (7.3-cm) long, golden talisman in Carolingian style, set with pearls and red and green stones, perhaps rubies or spinels, and emeralds. It is an encolpion, or portable reliquary, that dates back to the 9th century. This talisman is one of the pieces from the Reims Cathedral Treasury in France that has been kept in the Palace of Tau in Reims. The Talisman of Charlemagne is the only artifact that can be reliably linked to the Frankish king, unlike the Crown of Charlemagne and the Sword of Charlemagne.

The Talisman’s Origin

Charlemagne is supposed to have received this talisman in 801 as a gift from Harun al-Rashid (d. 809), the Caliph of Baghdad. The caliph also sent a water clock, the white elephant Abul-Abbas, and Chinese silk to the emperor.

The goldsmithing of the talisman is not in Arabic style. In 1166, when Charlemagne’s coffin was opened at Aachen in Germany, the talisman was supposedly discovered on the emperor’s chest.

It is made of gold using a highly intricate casting technique that was challenging during the Early Middle Ages. It is adorned with precious gemstone cabochons of round and rectangular shapes, as well as pearls. The absence of any figural or animal ornamentation is seen as further evidence of the talisman’s Arabic origin.

Design of the Talisman of Charlemagne

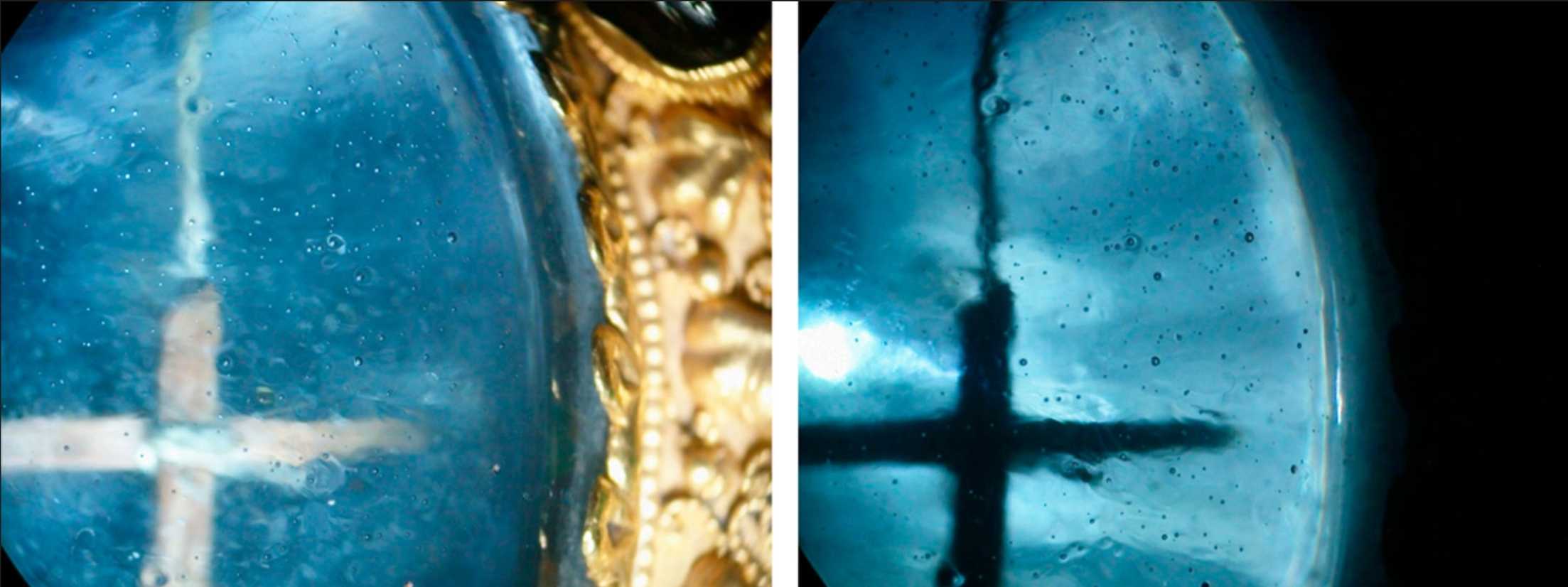

On one side of the Talisman of Charlemagne is a central sapphire of roughly 190 carats (1.34 oz; 38 g), opaque and of quite coarse size, concealing a relic of the True Cross that was transparently apparent through a glass cabochon that was definitely substituted in the 19th century.

Two pieces of wood, shaped like a cross, are housed in this talisman’s cabochon “heart.” These wood pieces are said to have originated from Jesus’ crucifixion on Calvary Hill. This inclusion has been believed to increase the talisman’s enchantment.

Gold is worked in filigree and granulation techniques, and all the precious stones are mounted in bezel settings. We can make out pearls, garnets, and emeralds set at the four corners of the jewel’s face and its edge.

The stones on the Talisman of Charlemagne are cabochon-cut and polished, bringing out their color rather than their shine. The 53 gems and pearls have been carefully placed in a harmonic pattern that takes into account their form and color.

Contradictions Regarding the Talisman of Charlemagne

The talisman itself is from the 9th century, but the gold chain is more modern. It’s possible that one of Charlemagne’s successors, not the emperor himself, ordered the talisman. During the late Middle Ages, many items were eventually linked to Charlemagne, despite having been created between the seventh and eleventh centuries.

The art historian Jean Taralon claimed that the Talisman of Charlemagne originally contained the Virgin Mary’s hair and milk. But it was later replaced with a piece of the holy cross in 1804 and then by the stone in 1870. However, this idea is at odds with the testimony that Marc-Antoine Berdolet, Bishop of Aachen, presented to Napoleon Bonaparte on 23 Thermidor, Year XII (or 1804).

According to that, the reliquary “contains a small cross made of the wood of the holy cross, found on the neck of Saint Charlemagne when his body was exhumed from his sepulcher in 1166.” Berdolet was testified to under penalty of excommunication, and his description excludes any substitution of the Talisman of Charlemagne.

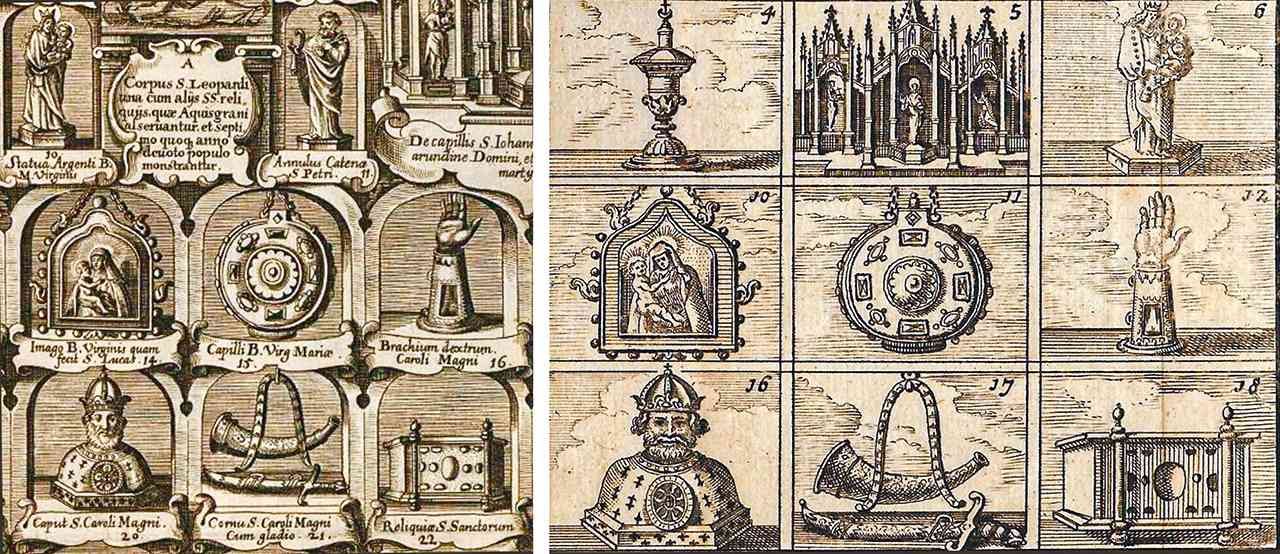

A few historians mention an engraving by W. Hollar that features a reliquary bearing the Virgin Mary’s hair. The engraving displays a part of the Treasury of Aachen from the 17th century. According to that, the Treasury of Aachen did not include the Talisman of Charlemagne.

Gemological Analysis of the Talisman of Charlemagne

Under the direction of the gemology professor Gérard Panczer, two campaigns (2016 and 2018) of on-site gemological analyses employing spectroscopic methods were conducted on the Talisman of Charlemagne for the first time. Geoffray Riondet, an expert in antique jewelry and a lawyer, was of particular assistance.

In particular, they allowed the provenance of the colored gemstones to be identified. Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) was formerly known for its sapphire mines. The center sapphire, which did not have any enhancement treatment by heating, was one of the biggest sapphires known in Europe before the 17th century.

Bernard Morel claimed that the relics with such large gemstones could not be produced until Philip II of France returned from the Third Crusade (1189–1192). Because gemstones of this size were very unusual in Europe at the time of Charlemagne and could only be obtained from the East.

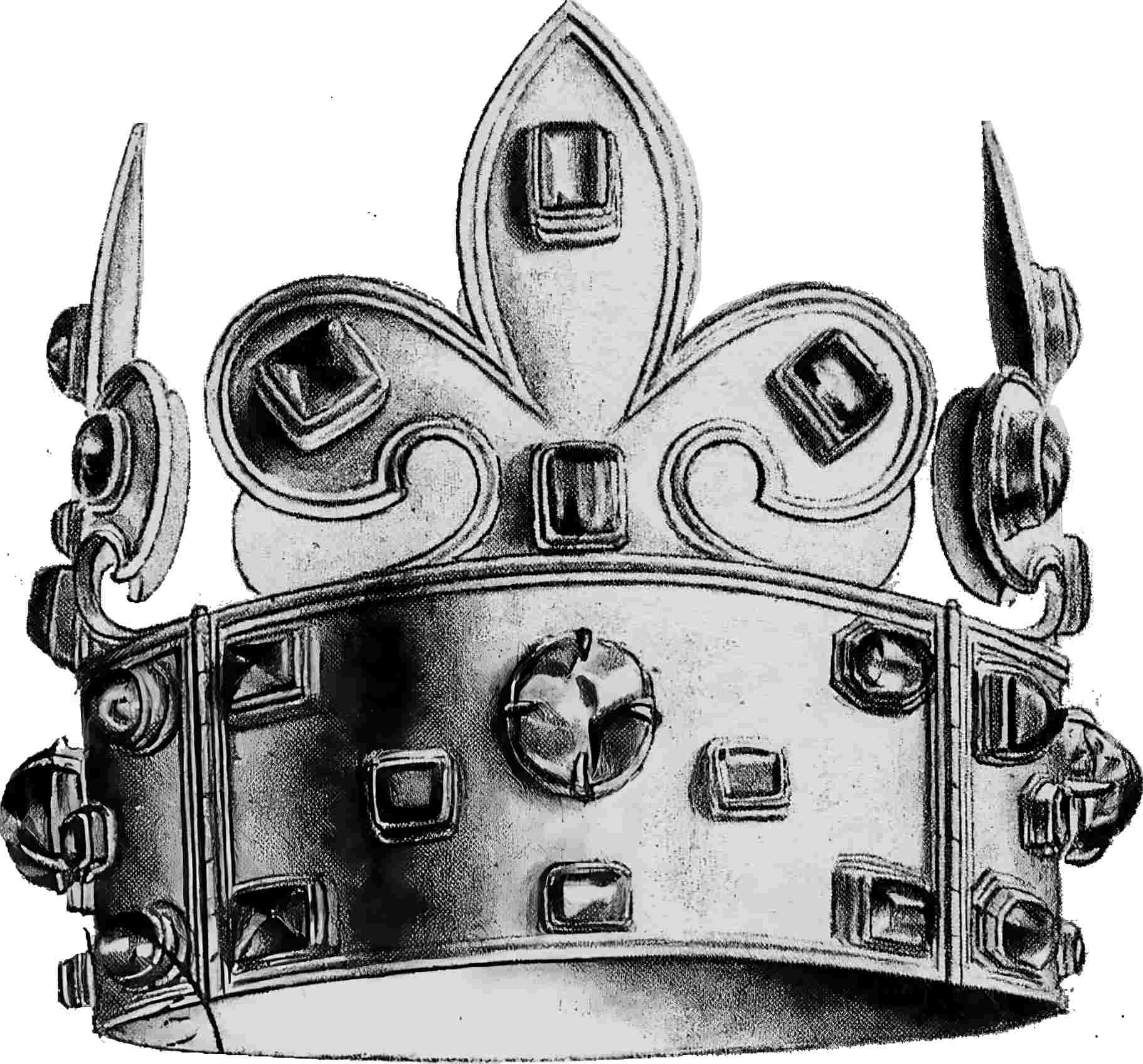

This theory of origin also holds true when examining the remarkably large gemstones adorning the Crown of Charlemagne.

The blue cabochon made from glass is doped with cobalt, which supposedly reveals a relic of the True Cross, and it had originally replaced a stone. Garnets were mined in southern India and Sri Lanka for the most part.

The emeralds have a similar chemical fingerprint to those found in Egypt’s Djebel Zabara. During the 1964 repair of the Talisman of Charlemagne, one of the stones was replaced with an emerald that currently displays the features of the Habachtal deposit in Austria.

History of the Talisman of Charlemagne

Caliph Harun al-Rashid supposedly sent this reliquary to Charlemagne of the Frankish Kingdom as a gift in 801. The keys of the Holy Sepulcher, the flag of Jerusalem, an ivory hunting horn, a saber from Damascus, and finally the Talisman of Charlemagne were all stored in the same treasury collection.

After being preserved in the Aachen Treasury until the early 19th century, the Talisman of Charlemagne is said to have been found at the exhumation of Charlemagne’s remains, either under Emperor Otto III in 1000 or under Frederick Barbarossa on January 8, 1166, but this is rather speculative.

According to others, the Talisman of Charlemagne was really crafted much later, in the 12th century. The earliest documentation of the talisman dates back to the 12th century; however, it wasn’t given the name “Talisman of Charlemagne” until 1620.

Charlemagne’s ownership of the talisman is not attested to in any historical records. Still, the scholar-abbet Alcuin (735-804), a contemporary of Charlemagne, wrote of the growing practice of carrying reliquaries with bits of saints’ relics around one’s neck.

This practice caught on and persisted in Catholicism for centuries, leaving room for the possibility that such a talisman was created much later.

During her coronation in 1804, Napoleon’s wife, Empress Joséphine, wore the Talisman of Charlemagne. It was later inherited by her daughter, Hortense de Beauharnais, who passed it on to her son, Napoleon III.

Later, Napoleon III gave it to Empress Eugénie de Montijo, who donated the talisman to the city in 1919 to help restore the cathedral in Reims, which had been bombarded during World War I.

The Talisman of Charlemagne at a Glance

What is the Talisman of Charlemagne?

The Talisman of Charlemagne is a 2.9-inch (7.3-cm) long, golden talisman in Carolingian style, set with pearls and red and green stones, possibly rubies or spinels, and emeralds. It is a portable reliquary dating back to the 9th century and is currently displayed at the Palace of Tau in Reims, France.

What is the origin of the Talisman of Charlemagne?

According to historical accounts, the Talisman of Charlemagne was supposedly gifted to Charlemagne in 801 by Harun al-Rashid, the Caliph of Baghdad. It is said to have been discovered on Charlemagne’s chest when his coffin was opened in 1166. However, there are contradictory theories suggesting it may have been crafted later, possibly in the 12th century.

What is the design of the Talisman of Charlemagne?

The Talisman of Charlemagne features a central sapphire of approximately 190 carats that conceals a relic of the True Cross. The talisman is adorned with pearls, garnets, and emeralds, and it is made of gold using filigree and granulation techniques. The gemstones are cabochon-cut and the overall design is devoid of figural or animal ornamentation.

Are there any contradictions regarding the Talisman of Charlemagne?

Yes, there are contradictions surrounding the talisman. While it is from the 9th century, the gold chain attached to it is more modern, suggesting a possible replacement. Additionally, there are differing accounts regarding the original contents of the talisman, with some claiming it contained the Virgin Mary’s hair and milk, while others suggest it held a piece of the holy cross.

References

- The Talisman of Charlemagne: New Historical and Gemological Discoveries – Gia.edu

- Medieval Art: Treasures of Saint Denis:Crown of Queen Jeanne d’Evreux – Pitt.edu

- The History of Charlemagne – George Payne Rainsford James, 1833 – Google Books

- Charlemagne – Father of a Continent – Alessandro Barbero, 2004 – Google Books