Sharovipteryx — A Mini-Dragon with Winged Legs

Zoologists from the University of Southern California in Los Angeles praised Game of Thrones for its realistic depiction of dragon wings. In fantasy works, dragons typically have four legs and wings on their backs, which would actually be impossible, as evolution has not produced animals with six limbs. The dragons in Game of Thrones are more believable, having only two pairs of limbs, with the front pair transformed into wings.

However, evolution in the real world has produced even stranger creatures than anything George R.R. Martin could imagine.

Take Sharovipteryx, for example. This gliding reptile’s remains were discovered in the Fergana Valley in Kyrgyzstan. It’s thought to be a distant relative of pterosaurs, which, incidentally, were not dinosaurs, despite the common misconception.

Unlike pterosaurs, which had wings on their forelimbs, Sharovipteryx had a membrane stretched between its hind limbs, allowing it to glide with its legs spread apart.

Though modest in size—only about 20 centimeters in length and weighing around 75 grams—this Kyrgyz mini-dragon was highly efficient aerodynamically. It was arguably even more efficient than modern flying squirrels and bats, as its outstretched legs and tail functioned like delta-shaped wings on a modern fighter jet. It also used membranes between its front limbs to maintain stability and prevent uncontrolled spins during glides.

Pakicetus — A Terrestrial, Predatory Whale

Whales are mammals. Despite their fish-like appearance, this is merely an illusion. Once upon a time, whales didn’t roam the oceans, sieving plankton through their teeth; instead, they roamed the land, chasing down prey and striking with powerful fangs.

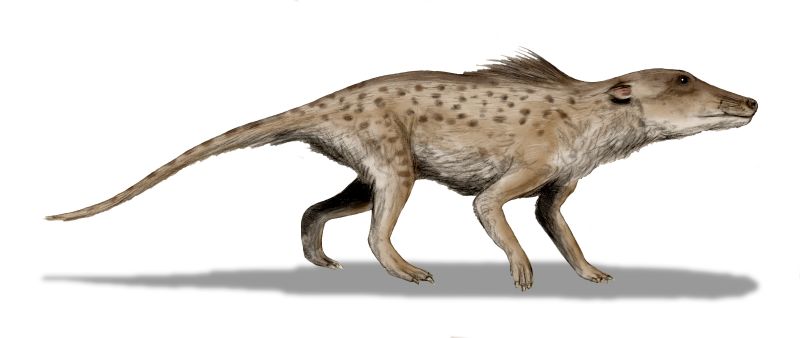

Take a look at this creature—Pakicetus, whose name Pakicetus literally translates from Latin as “Pakistani whale.” It lived about 50 million years ago and looked more like a wolf or hyena, measuring between 1 and 2 meters in length. However, instead of claws, it had small hooves at the tips of its fingers, and the structure of its legs resembled those of pigs or sheep.

Yes, a carnivorous, wolf-like hoofed animal with herbivorous ancestors that led a semi-aquatic lifestyle similar to a seal.

Pakicetus hunted both terrestrial animals that ventured too close to the water and aquatic animals and fish. Over time, its hooves disappeared, its fingers became flippers, its legs and tail fused, and it evolved into a mammal known as Ambulocetus, which later gave rise to modern cetaceans.

Few would have guessed that a predator would evolve into a peaceful giant feeding on plankton. But that’s exactly what happened. From an evolutionary perspective, this means that deer, pigs, camels, whales, and orcas are related and share common ancestors. This is why these animals are classified under a single order: Cetartiodactyla. Although, at first glance, whales and hooves seem worlds apart.

Hallucigenia — A Walking Stick with Spikes on Its Back

Looking at this creature, you might think it’s an artist’s fantasy envisioning alien life forms. But no, this was a real animal. Hallucigenia is a genus of extinct invertebrates that lived during the Cambrian period. They are distant relatives of modern tardigrades and arthropods.

Hallucigenia was first discovered in what is now Canada. It had a long body with numerous legs and spines along its back—essentially a spiny worm with two rows of clawed limbs. At the front, it had a proboscis-like head with teeth and eyes, along with several tentacles.

Initially, paleobiologists believed that this odd creature moved upside down, using its spines to walk. However, they later identified its correct orientation, distinguishing between its back and its legs.

Unfortunately, Hallucigenia was not large, reaching a maximum length of only about 6 centimeters.

Chalicotherium — A Horse Resembling a Gorilla

Gorillas are impressive creatures, blessed by nature with powerful arms and well-developed back muscles—imposing primates, indeed.

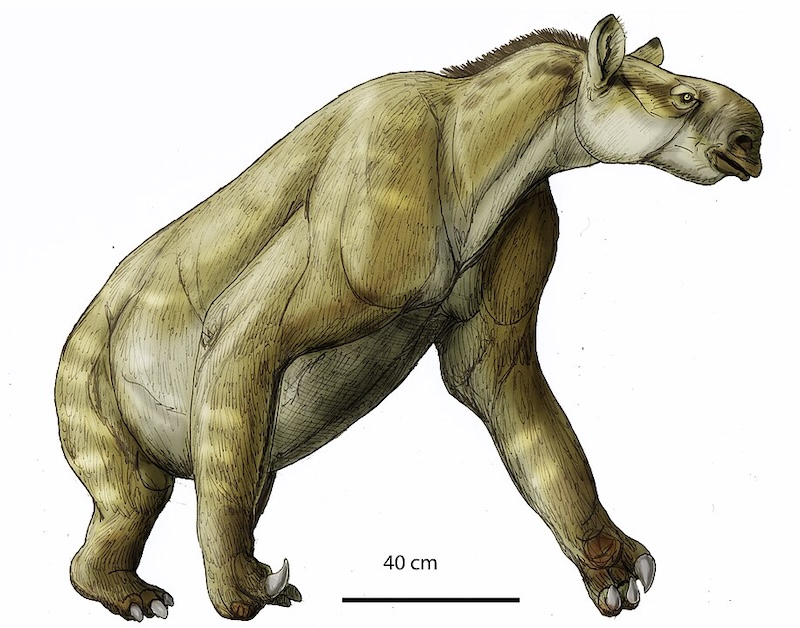

But gorillas only seem formidable because they never encountered chalicotheres. These creatures were relatives of horses that had not yet evolved hooves.

Chalicotheres could easily hold their own against any King Kong. They managed just fine against bear-dogs and saber-toothed cats without much trouble.

With their massive forelimbs, a single powerful right hook was enough to knock down any predator.

They had short heads, similar to zebras, and extremely muscular forelimbs, which they used to walk on their knuckles. A typical chalicothere stood 150 centimeters at the shoulder and weighed around 600 kilograms. They roamed Europe toward the end of the Miocene epoch, about 5.3 million years ago.

Dickinsonia — A Living Carpet with Frills

Around 560 million years ago, Earth’s conditions were vastly different from today. The land was barren, continents were arranged differently, and the Moon was closer to Earth, creating stronger tides. A year lasted about 400 days. This period is known as the Ediacaran period.

The “Gardens of Ediacara,” or the sea floors of that time, were paradise-like. Predation hadn’t yet evolved, and creatures hadn’t developed the concept of “chase and consume.”

One of the most fascinating and largest organisms of the Ediacaran biota was Dickinsonia. It resembled a round, living carpet, reaching up to 1.5 meters in diameter and segmented into sections.

Dickinsonia could crawl along the seabed using frilled edges but seemed to lead a mostly sedentary life, growing gradually larger. It fed on microorganisms, collecting them from the sea floor.

Scientists debated for a long time about what Dickinsonia truly was. Due to the presence of cholesterol in its structure, most biologists now believe it was an animal. However, some suggest it may have been a type of fungus or even belonged to an entirely extinct kingdom of life, unknown to science.