In 1793, as the French Revolution was fiercely fighting off Prussian and Austrian attacks, a new internal threat emerged in the west of France: the Vendée uprising. From simmering resentment over many years to scattered outbreaks of violence in only a few days. Things swiftly deteriorated into a full-blown civil war. The Vendeans, who were labeled “brigands,” made rapid advancements until they ran against the Terror and were put to the test by its regulations. As “counter-revolutionaries,” the “brigands” were brutally put down. The Vendée War lasted from March 1793 to March 1796, although the area was tormented by insurrectionary crises all the way up until 1832.

Background of the Vendée Wars

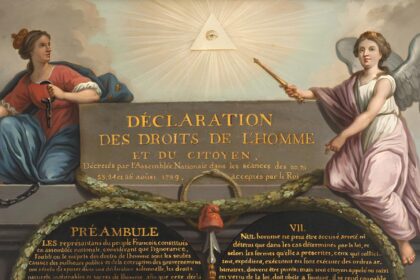

For a long time, the Vendée War had been defined by official history as the primary center of a royalist and Catholic counter-revolution, loyal to the monarch and the stubborn priests. But the roots of this conflict, which was driven by farmers at its core, were more knotty and harder to trace than that. The desire to restore the Old Regime was just one of several elements that led to the uprising among Vendeans, and although it may have been a motivating factor, the Vendeans’ calls for a return to monarchy were more of a symptom than a cause. And although there was some turmoil once the Ancien Régime (the Old Regime) collapsed and Louis XVI was executed, the Vendée did not rise up. The inhabitants of the Vendée embraced the Revolution and took part in it, although they did so with very little enthusiasm. However, the really poor peasants’ plight had changed little since 1789 and, in fact, often worsened. Moreover, the transfer of wealth did not help the general populace. Disparities in treatment between the city and the country also contributed to rising tensions. In truth, this uprising was not limited to the Vendée; similar uprisings occurred elsewhere in France, most notably in Lyon.

However, one of the Vendée’s distinguishing features was the region’s fervent Christian faith, which did not truly recognize the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and which welcomed and protected numerous recalcitrant priests. The peasants took up weapons in response to the Convention’s decision to conscript 300,000 men on February 24, 1793. While it is possible that some of the actors joined the Chouannerie, the Chouans (basically Bretons) waging guerilla warfare should not be confused with the Vendean revolutionaries moving in armed columns from town to town. In addition, the Vendée wasn’t where things really got going; the uprising began farther south, in the Mauges (south of Anjou), and then went west to the Breton Marsh (south of the Loire-Atlantic), and then south to the Vendée, and then east to Poitou.

The Vendée uprising of 1793

Peasant rioting greeted government officials on March 10, 1793, as they arrived to gather troops for the conscription ordered by the Convention that year. The situation quickly escalated into a bloody conflict in Machecoul. The “Bleus” (so named because of their uniforms) were welcomed with open arms at Tiffauges, Chemillé, and Saint-Florent-le-Vieil. On March 14, a true peasant army, led by the humble sacristan Jacques Cathelineau, captured Cholet. The Girondins, who were in charge of the National Convention at the time, were caught off guard and unable to respond to the political crisis.

The insurgents in Vendée made rapid strides, and at this point they had picked a side and rechristened themselves the “Catholic and Royal Army.” A Revolution that had ousted their priests and seemed to fail to deliver on its promises was something they intended to knock down. The royalist Charette de La Contrie and other nobility, such as the Count of La Rochejaquelein and the Marquis of Bonchamps, enlisted. On May 1, 1793, Thouars was conquered, then Fontenay-le-Comte, and finally Saumur on June 9. The Vendéens, still on the south side of the Loire, crossed the river and then dithered about whether to capture Tours and march on Paris or to safeguard their rear by seizing Angers and then Nantes.

Nantes: Failure of the counter-revolution

The decision to invade Nantes was taken. However, after taking Angers, the triumphant advance halted at the Loire Valley capital (of the Loire basin). Charette and his men ran upon a well-organized foe. As his forces fled, Cathelineau was murdered. Unfortunately for the Vendeans, Nantes would become the epicenter of Carrier’s repressive regime. The Montagnards (a political faction of the French Revolution opposed to the Girondins, who came to power at the end of May 1793) seized control of the Committee of Public Safety and swiftly responded by creating an “army of the west” to put a stop to the counter-revolution. Kléber led Republican battalions that marched out of Nantes and Niort and soon retreated the Vendéens. As a result, on October 17th, 1793, Cholet was once again under French control.

Virée de Galerne

La Rochejaquelein, however, had no intention of giving up. They had to cross the Loire River because of him. The next step after arriving in Laval was to go north to Granville. The Vendeans had high hopes that the Normandy port would be staffed by English soldiers. The Celts named this voyage “Galerne,” which means “northwest wind”. Even among the soldiers stationed at Château-Gontier, the diverse column of men, women, and children achieved some achievements and made some mistakes. However, they encountered several difficulties along the way, including having to retire from Granville and then Le Mans until finally calling it quits in Savenay, close to Nantes, on December 23, 1793. Upon hearing the Whites’ Blancs demands, the Blues -Bleus- (Republicans) reacted with violence. A little more combat occurred until March of the following year, when La Rochejaquelein was killed, but the first major conflict of the Vendée Wars was concluded.

The infernal columns

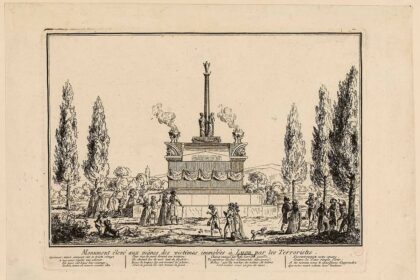

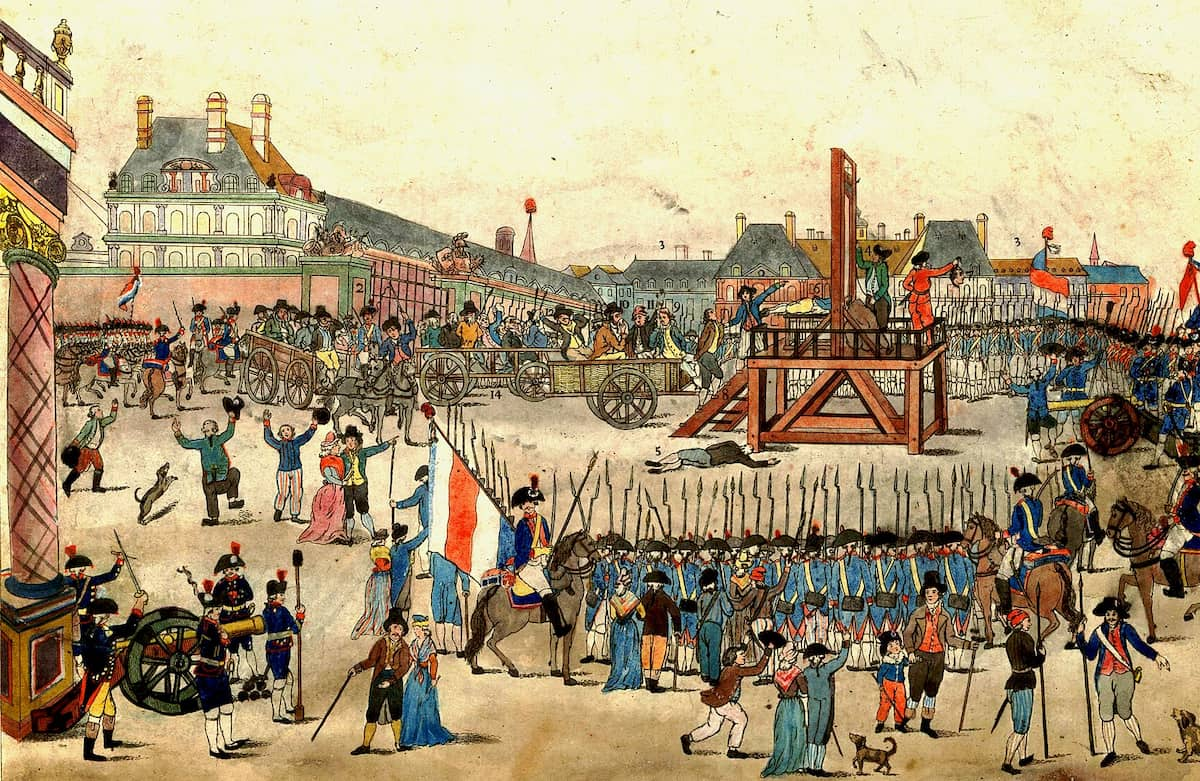

Hostilities persisted long after armed conflicts had ended. The Vendeans either allied with the Chouans or began following their practices. The Chouans counter-revolutionaries engaged in an early type of guerrilla warfare, launching periodic assaults against the government. Chouannerie originated in Brittany and Mayenne, despite its association with the Vendée War. Moreover, the rural areas of Vendée and the metropolis of Nantes were not immune to the Terror’s spread. Robespierre’s administration reacted with tremendous brutality since the Vendeans had made a name for themselves via atrocities. The government’s retaliation was predicated on the assumption that the populace had backed the rebels, and so it must be forced to pay for its actions. As a result, General Turreau’s forces carried out a campaign of scorched earth over the Vendée region, earning them the derogatory moniker “infernal columns” for their ruthless exactions, which included rapes, summary executions, and tortures. The Convention’s vote in favor of the “destruction of the Vendée” gave them tacit approval. When faced with these columns, Charette and Stofflet adopted similar routines to counter the demands made on them. The war’s bleakest hour has arrived. A revolutionary tribunal led by Jean-Baptiste Carrier was established in Nantes. The court at Savenay was postponed so that summary executions could begin when a large number of detainees were detained. Hundreds of people were put on closed boats and sank to the bottom of the river. Some 4,800 people were killed in this way.

The end of the Vendée Wars

An alternative, less extreme method was implemented after Robespierre’s downfall in July 1794. Charette signed the Treaty of La Jaunaye on February 17, 1795, and the Thermidorian Convention approved it in exchange for religious freedom and an end to compulsory military service in the Vendée. A few months later, nevertheless, the arrival of immigrants at Quiberon bolstered the Chouannerie and provided fresh hope for Charette and Stofflet. They were jailed at the start of the next year for trying to reorganize the Vendée resistance and restart the struggle. Tendencies toward insurrection occurred again in the not-too-distant future, but they were soon put down. The Directory declared victory in the Vendée War on July 15. The area did try to rise up again, particularly around the year 1800.

Results of the Vendée Wars

In addition to the Vendée, the Pays de Retz and a portion of Anjou were all profoundly affected by the Vendée War, the largest internal royalist danger the Revolution had ever experienced. Both sides committed atrocities on the land and the people inside it by using torture and murder. The “infernal columns” of Turreau, responsible for approximately 160,000 fatalities, marked the pinnacle of the genocide. These mass expulsions further exacerbated the region’s poverty by removing its entire population. It was a long time before the area was back to normal.

TIMELINE OF THE VENDÉE WARS

February 23, 1793: The Convention decides the conscription of 300,000 men

The revolutionary army seemed to be biding its time after losing Belgium and the Battle of Neerwinden. Although Paris was still distant from the Austrian or Prussian troops, the French government was wary of losing morale and giving their opponents any psychological edge, particularly because an English landing was always a possibility. In response, the Convention’s Girondin leaders planned to bolster the armed forces by adding 300,000 new recruits starting in March. Not everyone approved of this large conscription while the economy remained unstable. As a result, many areas responded forcefully, and uprisings spread widely in places like Lyon. First and foremost, though, this draft was what would finally set off the Vendée War.

March 10, 1793: Revolt of Machecoul

Since it was announced that 300,000 men would be conscripted to fight on the Eastern Front, the Vendée area has become increasingly unsettled. The citizens of Machecoul greeted the blue-clad patriots in charge of the conscription with pitchforks upon their arrival. Farmers and patriots came into direct combat as the battle escalated. Chemillé, Saint-Florent-le-Vieil, and Tiffauges were only a few of the towns that sprung up in a matter of days. It was the “Blues” who had been the target of the populace’s lynchings in the beginning. The populace rapidly formed an orderly group.

March 14, 1793: Cholet in the hands of the Vendéens

Within a few days after the revolt began, a modest peddler and sexton from Le Pin-en-Mauges named Jacques Cathelineau emerged as the leader of the Vendéen peasants. The peasant army, inspired by this figurehead, was able to conquer Cholet. Quickly, they moved toward the towns of Chalonnes-sur-Loire (south of Angers) and Thouars. As a result, the “Whites” started the Vendée War off with a string of successes.

May 1, 1793: Thouars in the hands of the Vendeans

The Vendéen columns moved southward down the Loire’s south bank, passing close to Angers on their way. The snatched Thouars. The revolutionaries from Vendean advanced even farther south at the end of May, when they captured Fontenay-le-Comte. They were unable to push eastward much farther than the Saumur-Thouars-Parthenay line.

May 25, 1793: Fontenay-le-Comte was taken by the Vendéens

The Vendean uprising originated in the Mauges area, but spread throughout the present-day Vendée’s southern regions when the key town of Fontenay-le-Comte fell to the rebels.

May 31, 1793: The Montagnards overthrew the Girondins

Robespierre led a group of Parisian “sans-culottes” and “Enragés” to the Convention in an effort to have the Girondin representatives expelled. They were blamed for being unable to handle foreign threats and accused of plotting the restoration of the monarchy.

A second uprising, headed by Marat on June 2, 1793, resulted in the arrest and detention of 29 representatives. Attempting escape resulted in the guillotine for the perpetrator. This event paved the way for the Montagnards’ eventual takeover and the establishment of the Terror.

June 9, 1793: The Vendeans take Saumur

The army of the Vendean took control of Saumur and then planned to cross the Loire. The river marked the northern boundary of the “Whites'” advance up to this point, while Fontenay-le-Comte marked the southern boundary. The chiefs debated whether to extend their rule to the west, or to go up the Loire to Tours and then march on Paris. It was deemed the most sensible option to march on Nantes. Nantes put up a strong fight against the Vendéens, whereas Angers surrendered without much of a fight.

June 12, 1793 : Cathelineau as generalissimo of the catholic and royal army

Jacques Cathelineau was named leader of the newly renamed “Catholic and Royal Army” of the Vendeans. The once-humdrum merchant was promoted to generalissimo and put in charge of his army by the illustrious La Rochejaquelein, de Charette, and d’Elbée. The latter group had enlisted in what was once an army of farmers.

June 29, 1793 : Nantes resists the Vendée insurrection

Cathelineau’s Vendeans army marched beyond the city walls of Nantes after capturing Angers. The city, however, was ready for the uprising: its citizens had decided to defend themselves. Consequently, 12,000 men were armed and ready to fight the 30,000 Vendée troops who had fanned out to the north and south of the city. The Nantais’ superior organization more than made up for their smaller numbers, and the Whites were ultimately compelled to retreat. Cathelineau was severely injured in the combat and passed away in the days that followed. The Vendeans halted their advance, and the conflict turned when Paris realized the full scope of the danger they posed. Now that Robespierre was in charge, the Convention was preparing a harsh response.

July 14, 1793: Death of Cathelineau

Cathelineau was mortally wounded at the Battle of Nantes and passed away in Saint-Florent-le-Vieil. A generalissimo of humble beginnings had been lost, but no one in the peasant army realized this. This death, unfortunately, will be kept secret for some time.

August 1, 1793: The Committee of Public Safety creates the Army of the West

Committee of Public Safety (Comité de salut public) has decided to take action in response to the danger posed by the Vendeans by assembling soldiers; they will become the army of the west. The army of Mayence, which had been under Kléber’s command, was among those that fell in July. The “Whites” of the Catholic and royal forces fought hard against this large deployment of soldiers at first, but the “Blues” swiftly got the upper hand after their victory at Cholet on October 17 and stopped the advance of the Vendée columns.

September 17, 1793: The Terror votes the “Law of Suspects”

On September 5, the Montagnards instituted the Terror in an effort to apprehend as many counter-revolutionaries as possible. By passing this legislation, they were able to speed up the court system and broaden the definition of offenses considered counter-revolutionary. “those who, by their conduct, their relations, their words, or their writings, have shown themselves to be supporters of tyranny, federalism, and enemies of liberty; those who cannot justify their means of existence and the fulfillment of their civic duties; those who have not been able to obtain a certificate of citizenship; former nobles who have not constantly shown their attachment to the Revolution; emigrants, even if returning,” etc. Once Robespierre was overthrown on September 9 of Thermidor Year II, this passage will no longer be relevant (July 27, 1794).

October 17, 1793: The Vendéens lose Cholet

Cholet was the site of the Vendeans’ second big loss, which came seven months after their first major win. Cholet, a key stronghold in the revolt’s birthplace, fell back into Republican hands. With their wives and children in tow, the 30,000 male Vendeans escaped the city and made their way to the Loire River, which was located around 40 kilometers north of Cholet. So, between 60,000 and 100,000 individuals made the crossing from the 18th to the 19th of October, bound for Brittany. Galerne, the Celtic term for a wind from the northwest, set sail on his first mission. The “Whites'” ultimate goal was to link up with the Chouans and make their way to Granville by way of Laval. They expected the English to make landfall at the Norman harbor.

November 14, 1793: The republicans forbade the Vendeans to enter Granville

The Vendéens’ first goal while setting out on the Galerne trip was to conquer Granville, but they were ultimately unsuccessful. A quick invasion of France did not seem to be something the English were eager to do. When the Galerne arrived, the Vendéens’ worst fear began.

December 13, 1793: The Vendéen army is decimated at Le Mans

Following their defeat in Angers a week before, the Vendée army marched on Le Mans. With their morale boosted by their success at Angers, the republican army concentrated a large portion of its numerically superior forces on the city of Le Mans. The conflict escalated quickly, and the Republicans ultimately prevailed. Only about half of the Whites’ original force made it through the combat unscathed, and they eventually fled south in order to recross the Loire. While the Catholic and royal troops did win a few battles during the Galerne campaign, none of them were decisive.

December 23, 1793: The Galerne Expedition ends at Savenay

It was estimated that between 15,000 and 20,000 survivors from the Galerne mission made it back to France after the devastating loss at Le Mans. They needed to go over the Loire River to achieve this. That’s what they were getting ready to do at Savenay, close to Nantes, when the Republican troops pounced. Kléber, Marceau, and Westermann’s troops were in charge, and their aim was to wipe out the counter-revolutionaries. Nearly 15,000 Vendéen dead were found in Savenay and the adjacent forests, while just 4,000 people managed to escape. Although the primary combat had stopped, the Vendée War itself had not ended. When Turreau’s hellish columns met Charrette’s and Stofflet’s soldiers in the following episode, a bloodshed on a grand scale was expected.

January 21, 1794: The infernal columns of Turreau melt on the Vendée

As a result of the defeat of the Vendée army at Savenay, the Convention determined to work for the “pacification” of the Vendée. Robespierre and his government wanted to implement their resolution from August 1 that advocated extreme measures to destroy the rebellion, including the destruction of crops and villages, the execution of suspects, and the confiscation of livestock, because of the widespread support the population had shown for the counter-revolution. It was Turreau’s job to put this “scorched earth” program into action. It was decided that most of the towns wouldn’t be destroyed, but a select few would be saved. Nearly five months passed as the devilish columns ramped up their extortion and slaughter.

February 17, 1795: Treaty of La Jaunaye

The Robespierriste The terror that was personified by the hellish columns of Turreau has subsided, and peace has returned to the Vendée. The Jaunaye accord brought a sense of calm that had been lacking. Charette negotiated a peace treaty to halt hostilities with the Vendéens and Chouans, but Stofflet rejected it. It restored religious freedom, ended mandatory military service, and granted amnesty to renegades in the Vendée. The Vendée War, however, was far from over.

June 23, 1795: Landing of Quiberon

At the same time that the Convention was trying to weaken the royalists as much as possible, the counter-revolutionaries from England arrived in the middle of Brittany. If they were wearing English uniforms, they were likely immigrants who had come to restore the monarchy. The Chouans, who had been preparing for this moment, joined the immigrants without delay. The forces of Charette and Stofflet were unable to join the celebration since they were unable to land in the Vendée. However, following the landing, they began to publicly reject the peace treaties they had already signed. Aside from a short period of success, the émigré army ultimately collapsed due to bad leadership and internal strife. The Republican army was able to push it back and destroy it in only a few days.

June 25, 1795: Charette took up arms again

Charrette rejected the peace of Jaunaye and resolved to resume fighting after the immigrants’ arrival. Even after the landing attempt failed, he continued to pursue his goals until he was arrested and executed a year later.

March 23, 1796: Execution of the Charrette

Soon after his arrest, Charette was put to death. In response to the emigrants’ arrival in Quiberon, he had once again taken up weapons. His execution, which came after that of Stofflet, effectively ended the Vendée’s organized resistance, but discontent continued.

July 15, 1796: The Vendée War ends

As a result of the deaths of Charrette and Stofflet, the Directory has declared an end to the unrest in the West. A civil war between Republicans and Royalists had been raging in the Vendée area since March 1793. Following a year of fierce and highly deadly fighting, the war continued with a brief respite, most notably because of the Treaty of Jaunaye. The area will attempt to rise again in 1800, but it will fail and take a long time to recover.

Bibliography:

- Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old Regime and the Revolution, pp. 122–23

- ean-Clément Martin, Contre-Révolution, Révolution et Nation en France, 1789–1799, éditions du Seuil, collection Points, 1998, p. 219

- Genocide A Comprehensive Introduction Adam Jones Page 6

- Mignet, François (1826). History of the French revolution, from 1789 to 1814. ISBN 978-1298067661.

- Anchel 1911, p. 980.

- James Maxwell Anderson (2007). Daily Life During the French Revolution, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-33683-0. p. 205