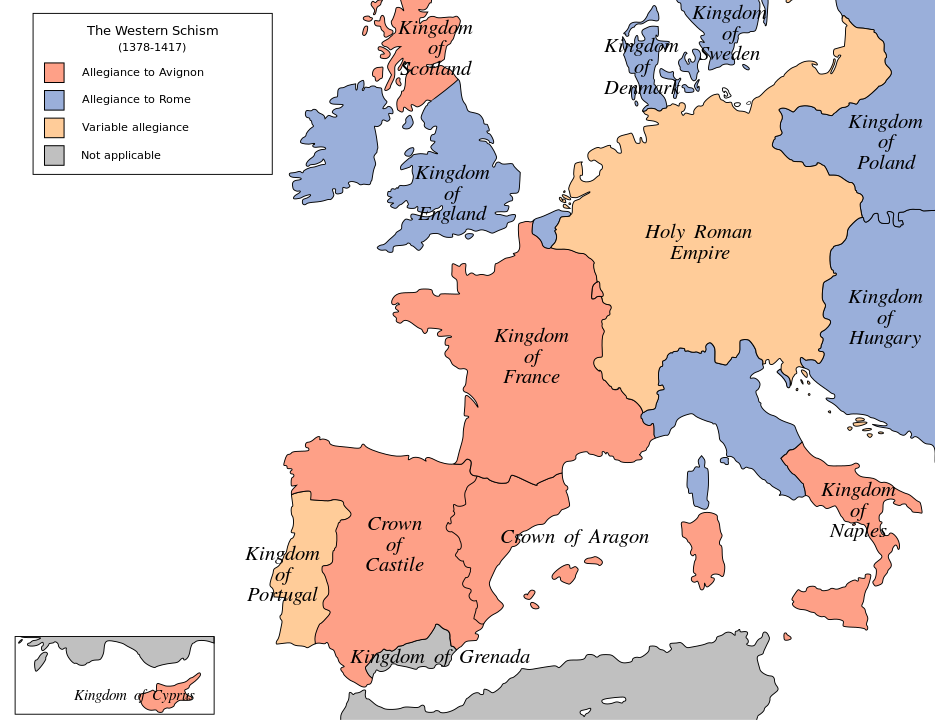

In 1378, the Great Western Schism emerged and lasted until 1417. The Catholic Church faced a grave problem because of this. There was a pope from the Avignon dynasty and another pope elected in Rome at that time. During the height of the struggle, the Church really had three heads since an antipope had been chosen in opposition to the other two. Internal problems made the institution’s credibility and power decline over time, particularly in relation to European politics.

The struggle was entangled with the Hundred Years’ War and went beyond questions of sacramental definition and religious theology. Reconciliation efforts began in the early 15th century, but they ultimately failed. The Council of Pisa initiated talks. But it was not until the Council of Constance in 1414 that a final decision was reached. The old leaders were condemned or deposed and a new pope was elected in 1417: Martin V.

Causes of the Western Schism

The Catholic Church was at the center of the Great Western Schism in the 14th century. Several factors contributed to this religious upheaval. To begin, the Hundred Years’ War weakened the political and economic structures of Europe. Concurrently, the 14th century was characterized by pandemics like the Black Death and famines due to poor harvests and other weather-related disasters. Significant changes in social structure were also present during the transition from feudalism to monarchy. Simultaneously, significant societal shifts were occurring. While the aristocracy’s economic standing improved, the Church’s elite looked out for number one: themselves.

The Church funded science and technology, but secular figures ultimately controlled its development. The Church went from being seen as a powerful, all-knowing entity to one that is hostile to reform. Other factors also contributed to the Western Schism. Political tensions and rivalry were stoked by events like the Visconti war and the Franco-Italian disagreement between Philip IV and the Papacy over the clergy tax, both of which were detrimental to Church unity.

Some of the key figures of the Western Schism include Pope Gregory XI, who brought the papacy back to Rome from Avignon, Pope Urban VI, who was elected as his successor, and the later antipopes Clement VII and Benedict XIII. In addition, the Council of Pisa tried to resolve the schism by electing a third pope, Alexander V.

How Did the Western Schism Occur?

The Great Western Schism began in 1378 and ended in 1418; it was a major crisis for the Catholic Church that lasted nearly 40 years. It can be divided into two main phases:

- The first lasted from 1378 to 1394. In 1377, Pope Gregory XI left Avignon for Rome. He died the following year. However, this election signaled the division of the College of Cardinals. A double papal election followed. In Rome, Urban VI was elected. In Avignon, Clement VII was elected. During this period, Europe was in the grip of various conflicts. In addition to the Hundred Years’ War, Italy was the focus of numerous struggles for influence and control. The Great Western Schism led to conflicts in which kingdoms sided with Rome or Avignon, as in the Crusade of Henry the Despenser. The Holy Roman Empire also faced problems of political stability. Popes Urban VI (Urbanus) and Clement VII died in 1389 and 1394, respectively. However, the Western Schism continued.

- The years between 1394 and 1417 saw the second phase of the Great Western Schism. Priests, church authorities, and rulers of kingdoms and empires struggled to find peaceful solutions to the Catholic dilemma that had reached an impasse. There was an initial failure. In 1409, at the Council of Pisa, a consensus was reached. Both popes, Gregory XII of Rome and Benedict XIII of Avignon, were deposed. In 1405, Alexander V became pope. He was now an antipope, since the previous two popes had refused to recognize their deposition.

With the choice of antipope John XXIII as Alexander V’s successor, the situation deteriorated further. There began to be talk of a church with three popes and three heads. The Western Schism was finally resolved at the Council of Constance in 1415. Until 1418, a number of significant events occurred. Gregory XII resigned, John XXIII fled, and Benedict XIII was deposed, although he did not accept this decision. In 1417, Martin V became the 206th official pope of the Catholic Church.

Consequences of the Western Schism

The Western Schism had a significant impact on the Western world. Antipopes such as Alexander V and John XXIII were elected as a result of the crises of the Catholic Church. The authority of the Catholic Church was eventually challenged. This concerned not only the structure of the Church, but also the degree to which the sacraments reflected different theological trends. Because of this and the subsequent crises that led to the formation of councils, the power and influence of the church was severely eroded. The idea of conciliarism was strengthened at the Council of Constance. The ecumenical councils were seen as more authoritative than the pope himself.

The dissolution of the Western Schism coincided with the rise of distinct national identities. The Church had a hard time asserting its authority after years of religious strife. Certain kings put some mechanisms in place. Under Charles VII, for example, the French Church gained greater independence. The clergy in France gained full independence. The Protestant Reformation had its roots in the Great Western Schism. It also helped accelerate the abandonment of the feudal system throughout Europe. A monarchical system was adopted, and kingdoms and empires were modernized.

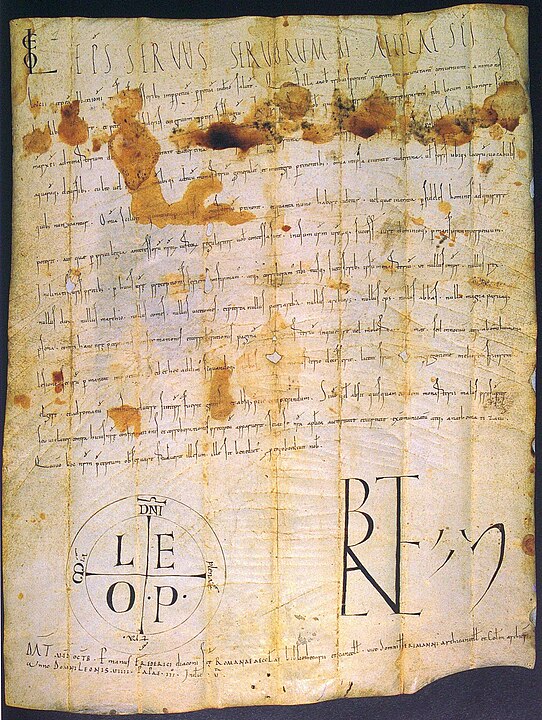

The East-West Schism of 1054

In 1054, the Great East-West Schism took place. It marked the break between the Orthodox and Catholic Churches in Byzantium and Rome, respectively. Political tensions and disagreements over the structure of the church and the meaning of religious scripture were primary factors. Cultural and linguistic differences exacerbated tensions over contentious issues such as papal primacy and the use of unleavened bread in the Eucharist. In 1054, the legates of Pope Leo IX and Patriarch Michael Cerularius of Constantinople excommunicated each other, separating their respective churches.

The schism severely damaged the already tense relations between the two Christian groups. There was often a palpable undercurrent of animosity between members of the two faiths. They chose to look the other way when tensions flared, especially during the Ottoman invasion of Byzantium. Although they had no intention of uniting, the excommunications were lifted in a “joint declaration” between Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras in 1965.

Key Dates of the Western Schism

September 20, 1378: Antipope Clement VII begins his pontificate

A council in Fondi elects Robert de Genève as antipope of Avignon. He takes the name Clement VII. This event marks the beginning of the Great Western Schism and the Church now has two popes: Clement VII and Urban VI. The second pope followed an authoritarian policy and gradually lost all his allies. Clement’s papacy lasted until his death in Avignon on September 16, 1394. He was succeeded by Benedict XIII.

November 2, 1389: Papacy of Boniface IX

November 2, 1389, was the date on which Boniface IX succeeded Urban VI as pope in Rome. Boniface IX, a Neapolitan nobleman, took advantage of his papacy to abolish the independence of the Roman Commune and regain control of the cities and castles of the Papal States. During his reign, Clement VII and Benedict XIII established a papal court in Avignon. Boniface IX, who was ill, died on October 1, 1404. He was succeeded by Innocent VII.

September 28, 1394: Benedict XIII begins his pontificate

On September 28, 1394, Pedro de Luna took the name Benedict XIII and assumed the Papacy of Avignon for a papacy that would last until his death in 1423. Considered an antipope by the Catholic Church, Benedict XIII succeeded Clement VII and counted among his allies to fulfill his duties: France, Castile, Portugal, Aragon, Scotland, and the Kingdom of Cyprus.

October 17, 1404: Election of Pope Innocent VII

Boniface IX is dead. Innocent VII (Cosimo Migliorati, born in Sulmona in 1336) became the 202nd Pope of Rome, a position he held until his death in 1406. As soon as his election against the Avignon envoy, the antipope Benedict XIII, was confirmed by the cardinals, the city of Rome was shaken by a Ghibelline rebellion, which King Ladislaus I of Naples tried to suppress. During his short reign, he failed to put an end to the Great Western Schism (1378–1417).

November 30, 1406: Election of Pope Gregory XII

Gregory XII (born Angelo Correr in Venice circa 1325) became the 203rd Pope of Rome. During his pontificate, which lasted until his resignation in 1415, he tried hard, but without success, to negotiate with the antipope of Avignon, Benedict XIII, to reduce the Great Western Schism. Despite his rejection at the Council of Pisa (1409), he did not resign until the Council of Constance (1414–1418), which ended the Great Schism with the election of Martin V (Martinus). He then became Cardinal-Bishop of Porto. In 1417, Recanati disappeared in the Marche.

February 18, 1407: Withdrawal of Allegiance to Antipope Benedict XIII

New decrees on the withdrawal of spiritual allegiance from Antipope Benedict XIII are established. The deposition of 1407, a French policy designed to force the rival popes of Rome and Avignon to abdicate in the wake of the Great Western Schism and administered by the University of Paris with the support of the Duke of Burgundy and the Parliament of Paris, was less successful than its predecessor of July 23, 1398. Confined to his castle, Benedict XIII refused to submit.

April 21, 1407: Agreement between Benedict XIII and Gregory XII

The delegate of the antipope Benedict XIII (1324–1423), who had taken refuge in the Monastery of Saint-Victor in Marseille after fleeing Avignon, receives the Roman delegate Gregory XII (1325–1417). The following June 11, the convention, ratified by King Charles VI of France, agreed to a meeting between the two popes in Savona to resolve the Great Western Schism. The talks ended in failure: Benedict XIII traveled to the Italian city on September 24, but was sidelined by Gregory XII.

June 1408: Convening of the Council of Pisa

Eight Roman cardinals gathered in Livorno (Tuscany) and seven cardinals from Avignon convened the Council of Pisa to resolve the Great Western Schism. Meeting from March 23 to August 7, 1409, the council deposed Pope Gregory XII of Rome (1325–1417) and Pope Benedict XIII of Avignon (1324–1423) and elected a third pope, the Greek Franciscan Alexander V (1340–1410). However, the two popes refused to abdicate, considering the council illegal, and even worse, a third (illegitimate) pope laid claim to the Holy See.

December 9, 1413: Sigismund I and John XXIII convene the Council of Constance

Fulfilling the request of Sigismund of Luxembourg, the antipope John XXIII issued a proclamation convening the XVI Ecumenical Council of Constance, scheduled to convene on November 1, 1414. Three popes had been vying for the Holy See since the Council of Pisa (1409) and demands for reform in Bohemia were being voiced. The Council, which lasted until 1418 and was presided over by Cardinal Jean Allarmet de Brogny, brought an end to the Great Western Schism.

November 16, 1414: Opening of the Council of Constance

To end the Great Western Schism, Antipope John XXIII called the 16th Ecumenical Council, which got under way in Constance at the request of his patron, Sigismund I of Luxembourg. The Germanic Roman Emperor thus decides to get rid of the College of Cardinals in order to organize the chaos paralyzing the Church. Since the Council of Pisa (1409), there have been three contenders for the Holy See: Benedict XIII, antipope of Avignon; Gregory XII, antipope of Rome; and the “Pisan” Alexander V, who succeeded John XXIII (died in 1410).

March 26, 1415: The Council of Constance Declares Itself Above the Pope

The Council of Constance begins its third session. Charged with the task of putting an end to religious anarchy, the Council declares that it will not leave until it has restored the unity and discipline of the Church by the decree of Haec Sancta (April 6), asserting its supremacy over the Pope. John XXIII, recognized as legitimate by the Council but already weakened by the new voting system (one vote per nation, not per person), was arrested and deposed.

July 4, 1415: Antipope John XXIII Resigns

At the Council of Constance, Gregory XII, Pope of Rome, was forced to resign by the procurator on the principle of “sacrificing his dignity for the peace of the Church”. Benedict XIII, after deposing John XXIII of Pisa, resisted, but he too was deposed. This allowed the Council Fathers to finally solve the problem of the Great Western Schism by electing Oddone Colonna of Rome as Martin V (November 11, 1417).