What Are Wormholes and Do They Actually Exist?

One foot here, the other thousands of light-years away.

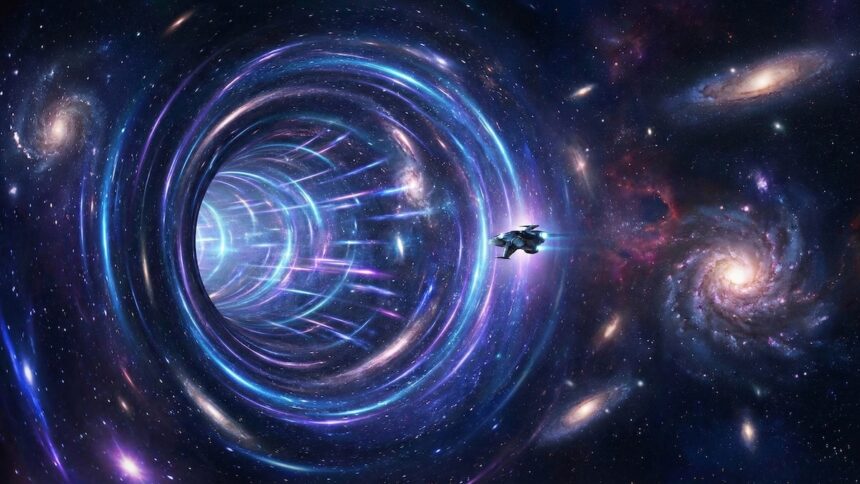

If you’ve watched the film “Interstellar” or the series “Stargate,” you’ve probably imagined stepping through a portal and ending up in another galaxy. The science fiction plots of these works revolve around wormholes—hypothetical tunnels in spacetime that could connect distant corners of the Universe.

But do they exist in reality? And can instantaneous travel from one point to another become a reality? To answer these questions, we need to understand what lies behind the term “wormhole,” how scientists envision them, and what laws of nature allow—or forbid—such journeys. Let’s explore.

What Is a Wormhole?

A wormhole, or Einstein-Rosen bridge, is a hypothetical object predicted by Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Simply put, it’s a kind of tunnel or bridge between two points in spacetime that potentially allows travel between them faster than by taking the “direct” path.

To visualize how this works, imagine a sheet of paper. On it are points A and B, located far apart. If you walk from A to B along the surface of the paper, the journey would be long. But if you fold the paper so the points are next to each other and poke through it with a pencil, you can get from one place to another almost instantly. That hole is analogous to a wormhole: it shortens the path by curving spacetime.

How Are Wormholes Studied?

The history of the wormhole concept began in 1916. Austrian physicist Ludwig Flamm, studying Einstein’s equations, discovered that black holes could theoretically have counterparts—white holes. While the former pull in everything that approaches, the latter cannot accept anything inside but can eject matter outward. Flamm suggested that black and white holes might be connected by a special spacetime tunnel—essentially, a wormhole.

Later, in 1935, Einstein and his colleague Nathan Rosen mathematically described such structures and called them Einstein-Rosen bridges. But it turned out they were unstable: the tunnels instantly collapse under the action of gravity, not allowing even light to pass through.

A breakthrough came in the 1980s when physicists wondered: could a wormhole be made traversable?

Among them was Kip Thorne, a consultant for the films “Contact” and “Interstellar.” Together with colleagues, the scientist concluded this was possible—but it would require exotic matter with negative energy. Such matter could work against the force of gravity, affecting the tunnel walls and holding them open. Similar effects do occur in quantum field theory, but on such minuscule scales that real travel is out of the question.

Nevertheless, the idea that wormholes could be stabilized meant they ceased being purely mathematical abstractions and are now considered potentially real objects.

How Scientists Search for Wormholes—And Do They Find Any?

Scientists haven’t discovered a single wormhole yet, but that doesn’t stop their search. Here’s how science tries to find “portals” in spacetime.

Theoretical Models

In 1999, physicists Lisa Randall and Raman Sundrum proposed a model in which our four-dimensional Universe is actually part of a larger five-dimensional space. In this theory, gravity partially “leaks” into the fifth dimension. This could explain why gravity is much weaker for us than other interactions—such as nuclear or electromagnetic forces. Wormholes could pass through this additional dimension and gain stability there thanks to the peculiarities of gravity and spatial geometry.

In 2021, Juan Maldacena and Alexey Milekhin described a theoretical model in which a wormhole could exist even in four dimensions without collapsing. Their calculations used a mixture of gravity, electromagnetism, and special light particles—fermions. The latter create a negative energy effect capable of keeping the tunnel open.

So far, this exists only at the level of formulas, but the model shows that stable wormholes don’t contradict known laws of physics.

Another direction relates to so-called quantum wormholes. From a physics standpoint, even the “emptiest” vacuum is actually filled with tiny energy fluctuations—a kind of bubbling foam of virtual particles that appear and disappear in fractions of a second. In this seething environment, scientists theorize, tiny wormholes may occasionally appear—so small and short-lived that we have no way to detect them. But modern science can’t yet confirm this, so quantum wormholes remain hypothetical.

Experimental Methods

Since 2015, when the LIGO observatory first detected gravitational waves, scientists have gained a new tool for searching for wormholes. These waves arise when two very massive bodies collide—such as black holes or neutron stars. In theory, if wormholes collided instead of black holes, the signal would be different. For example, after the main burst of gravitational waves, an “echo” might appear—energy reflecting from the tunnel walls. No such signals have been detected yet, but improved detector sensitivity in the future could change that.

Another method is analyzing cosmic microwave background radiation, the thermal “echo” of the Big Bang. If wormholes existed in the early Universe (especially large ones), they could have affected matter distribution. For instance, creating anomalously empty areas among galaxies or leaving traces as strange temperature fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background. Such distortions are indeed observed and continue to be analyzed as possible clues.

Very recently, physicists began using quantum computers to model wormhole behavior under conditions impossible to reproduce in a laboratory. In 2022, Google Quantum AI’s team conducted an experiment that successfully transmitted information between parts of a quantum system using an effect resembling teleportation. This process mimicked a particle passing through a tiny wormhole in an artificial spacetime model. Of course, this isn’t a real wormhole but a mathematical simulation—yet it helps bring us slightly closer to the answer.

What Might Prevent Travel Through Wormholes?

Even if such tunnels exist, travel through them would involve extreme conditions that call into question the possibility of survival.

Extremely High Temperatures

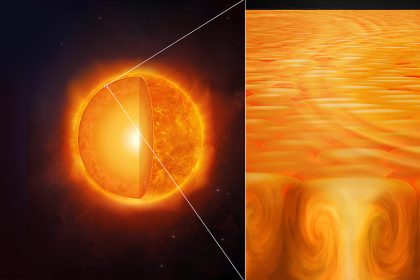

In 2023, scientists modeled wormholes through which matter actively passes. It turned out that plasma vortices form in their “throat,” heated to millions of degrees—thousands of times hotter than the Sun’s core. Under such conditions, any spacecraft would vaporize before even entering the tunnel. Moreover, at these temperatures, nuclear reactions could begin, turning the flight into a thermonuclear catastrophe.

Lack of Exotic Matter

According to classical theory described above, stabilizing wormholes requires exotic matter with negative energy. The problem is that for an apple-sized wormhole, you’d need an amount of negative energy comparable to what the Sun produces over millions of years. Modern science doesn’t know how to collect that much exotic matter. This makes creating artificial wormholes practically impossible with current technology levels.

Time Complications

According to theoretical models, such as the Randall-Sundrum model, a flight through a wormhole might take a passenger only a few seconds. But for an external observer, this could look like 10,000 years. This is due to effects related to movement at speeds close to the speed of light: for the traveler, time moves more slowly—as in “Interstellar.”

In the end, you’d return to a future where familiar planets and civilizations might no longer exist.

Another risk is temporal paradoxes. For example, if someone could return to the past and influence their own birth, this would violate causality. According to Stephen Hawking’s theory, to prevent this, nature has “chronological censorship”: laws that prevent wormholes from becoming time machines.

Near-Light Speed

To overcome a wormhole’s gravity, a ship must accelerate to near-light speed. This would create enormous g-forces, exceeding Earth’s gravity by dozens of times. Even an experienced astronaut would lose consciousness under such conditions. Not to mention the ship’s hull would need to be made of materials that don’t yet exist.

What’s the Bottom Line?

Wormholes remain one of modern physics’ most captivating mysteries. On one hand, they’re predicted by Einstein’s equations and could exist within quantum theories. On the other, their discovery and use seem nearly impossible due to extreme conditions.

But the very fact that science seriously considers such objects already changes our understanding of the Universe. Studying wormholes helps advance science, explore the nature of time, and properties of matter. Even if “cosmic portals” remain hypothetical, their mathematical models serve as a bridge between general relativity and quantum mechanics—two pillars of modern physics.

Perhaps in the future, new technologies—quantum computers, gravitational telescopes, or experiments with exotic matter—will shed light on this mystery. But for now, wormholes remind us how much unexplored territory the cosmos still holds and inspire scientists to seek answers beyond ordinary reality.