Most of the “witches” persecuted in Europe from the 15th century onwards were in fact midwives and healers, heirs to a long tradition of secular medical practice that was more pragmatic than theoretical.

But to tell the story of these experts (before they were totally evicted), researchers face several obstacles: information is scarce and disparate, fragmented into many very different sources; biographical sources, for example, but also economic, judicial, and administrative sources. Sometimes only first names or surnames remain, such as those of women inscribed in the Ars Medicina of Florence (a medical treatise), or that of the apothecary nun Giovanna Ginori, recorded in the tax registers of the pharmacy where she worked during the 1560s.

Nevertheless, this research allows us to better understand how women were gradually excluded from medicine, its practice and studies, by an institutional and hierarchical system totally dominated by men.

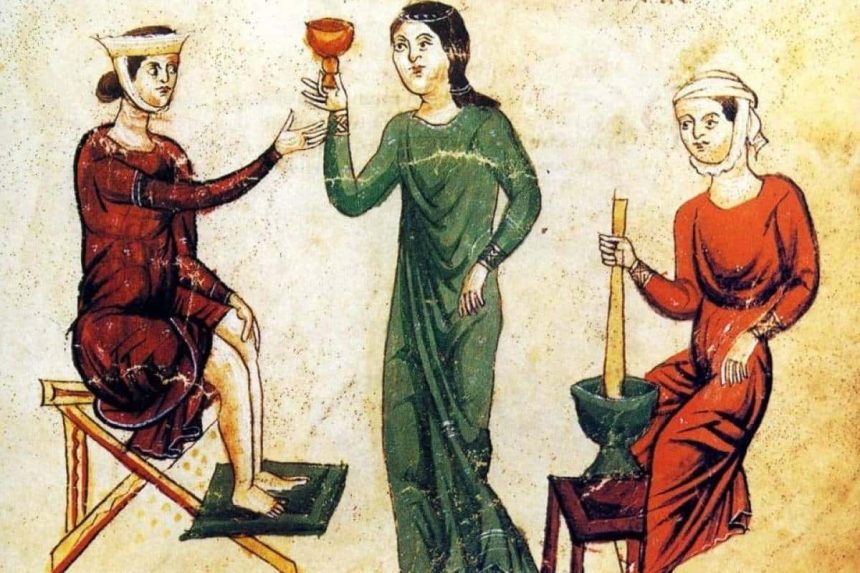

Schola Medica Salernitana

We must first mention the most famous medical school active at the beginning of the Middle Ages, that of Salerno, the Scola Salernitana. It counted among its ranks several women physicians: Trota (or Trotula), a pioneer in gynecology and surgery, Costanza Calenda, Abella di Castellomata, Francesca di Romano, Toppi Salernitana, Rebecca Guarna and Mercuriade, who are fairly well known, as well as those called the mulieres salernitanae.

Unlike the women doctors of the School, the mulieres worked at a more empirical level. Their remedies were examined by the School’s doctors, who decided whether or not to accept them, as evidenced by Giovanni Plateario‘s manual Practica Brevis and Bernard de Gordon‘s writings. In Salerno, Christian, Jewish and Muslim scholars crossed paths; different cultures coexisted, making the School an exceptional place, a breeding ground for scientific encounters and influences.

Women Accused of Practicing Illegally

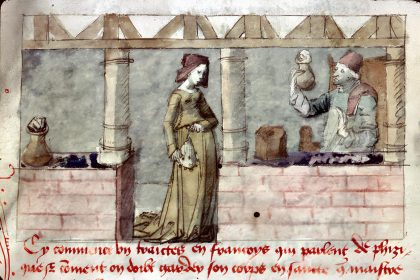

However, from 1220 onwards, the situation became complicated because no one could practice medicine without being a graduate of the University of Paris or without having obtained the agreement of the doctors and the chancellor of the University, under pain of excommunication. Let us cite the example of Jacoba Felicie de Alemannia. According to a document produced by the University of Paris in 1322, she treated her patients without “really” knowing medicine, that is, without having received university education, and was liable to excommunication; consequently, she had to pay a fine.

The records of the dispute describe the course of a medical examination given by this woman: we learn that she visually analyzed urine, took pulses, palpated the patient’s limbs, and that she treated men. This is one of the rare testimonies that mentions the fact that women also treated men.

The trial of the young doctor took place during a time when those who were not university graduates were being denounced and condemned. Before her, Clarice of Rouen had been excommunicated for practicing medicine for the same reason – treating men – while other women skilled in medicine were again condemned in 1322: Jeanne the lay sister of Saint-Médicis, Marguerite of Ypres, and the Jewish woman Belota.

In 1330, the rabbis of Paris were also accused of illegally practicing the art of medicine, as well as some other “healers” who passed themselves off as experts without being so (according to the authorities): they were taxed as impostors, even if they were competent. In 1325, Pope John XXII, opportunely solicited by the professors of the University of Paris after the Clarice affair, addressed Bishop Stephen of Paris, ordering him to forbid those ignorant of medicine and midwives from practicing medicine in Paris and the surrounding area, insisting that these women practiced sorcery.

The Formalization of Studies

The progressive prohibition of the practice of medicine for the female gender took place parallel to the formalization of the canon of studies, the beginning of meticulous control by teaching hierarchies and corporations, increasingly marginalizing women doctors.

However, they continued to exist and practice — among the Italians, we know of the Florentines Monna Neccia, mentioned in a tax register, the Estimo of 1359, Monna Iacopa, who treated plague victims in 1374, the ten women registered with the corporation of doctors in Florence — the Arte dei Medici e degli Speziali — between 1320 and 1444, or the Siennese Agnese and Mita, paid by the City for their services in 1390, for example.

However, practicing medicine became very risky for them, with suspicions of witchcraft becoming increasingly heavy.

Unfortunately, official sources lack data on women doctors, as they practiced in a society where only men accessed the highest positions.

Nevertheless, the historical framework that can be reconstructed shows the existence not only of women who were experts and practiced the art of medicine, but also of women doctors who studied, often unofficially — most were educated by their father, brother or husband.

Women Doctors in Literary Sources

Non-institutional sources, such as literary texts, are very precious. For example, Boccaccio mentions a woman doctor in the Decameron. The narrator, Dioneo, speaks of a certain Giletta di Nerbona, an intelligent woman doctor who managed to marry the man she loved — Beltramo da Rossiglione — as a reward for having cured the King of France of a chest fistula. Boccaccio has Giletta, who perceives well the sovereign’s lack of confidence in her, as a woman and young woman, say:

I remind you that I am not a doctor thanks to my science, but with the help of God and thanks to the science of Master Gerardo Nerbonese, who was my father and a famous doctor in his lifetime.

Boccaccio thus presents us with a woman expert in medicine in a simple and natural way: perhaps this is a sign that he was referring to situations more common and known to his readership than is generally believed. What Giletta says reflects a reality of the time for women who practiced medicine: what she knows, she learned from her father.

There is particularly a lot of data concerning Jewish women doctors, active particularly in southern Italy and Sicily, who learned the medical art in their families.

The University of Paris played a very important role in the historical process of standardization and institutionalization of the medical profession. In her article “Women and Health Practices in the Register of Pleadings of the Parliament of Paris, 1364-1427,” Geneviève Dumas clearly showed the importance of Parisian judicial sources from the 14th and 15th centuries, because they contain the memory of women who were condemned for illegally practicing medicine or surgery. Dumas published two trials: the one conducted against Perette la Pétone, a surgeon, and against Jeanne Pouquelin, a barber (barbers were also authorized to perform certain surgical acts).

As the teaching of medicine at the University of Paris became the only valid training in Europe and the School of Salerno lost influence, women were gradually excluded from these professions.

The progressive disappearance of women doctors is to be related to ecclesiastical prohibitions, but also to the gradual professionalization of medicine and the creation of increasingly strict institutions such as Universities, Arts and Guilds, founded and controlled by men.

In Europe, it would take until the mid-19th century for the first graduated women doctors to be able to practice, not without facing sharp criticism.

What does science owe to Marian Diamond, the woman who dissected Einstein’s brain?