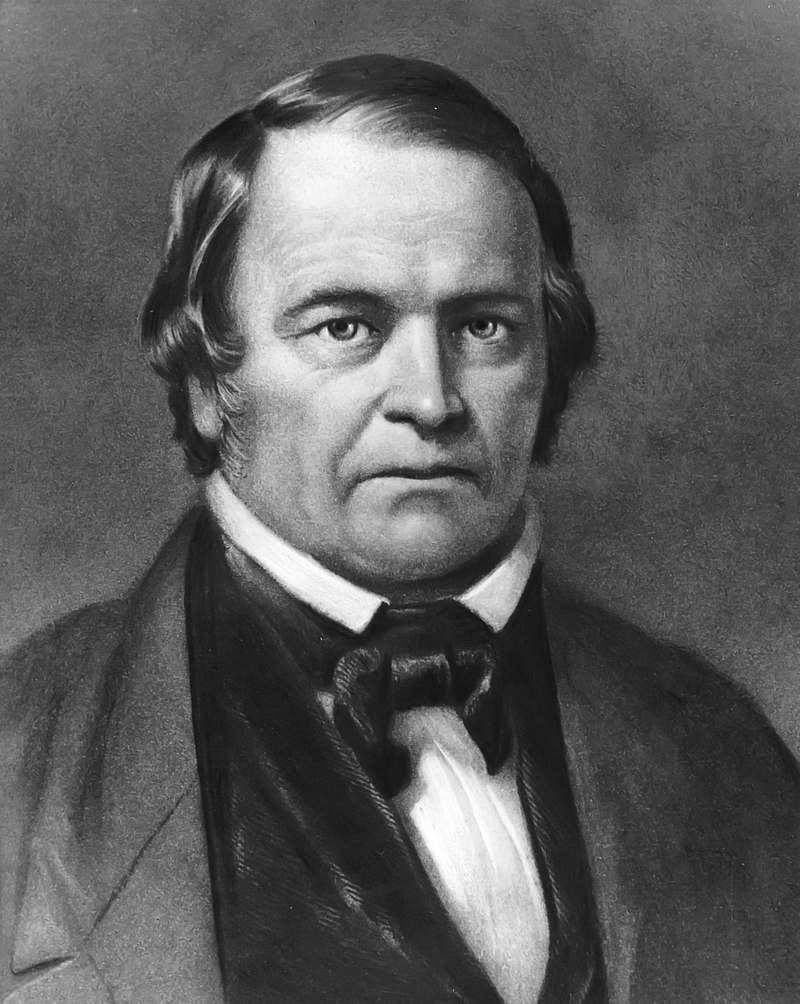

Two hundred years ago, American William Miller was inspired by a Bible text to declare the end of the world was near. Let’s shed light on the events that led to this conclusion. While the beginning and conclusion of religious movements are often recorded, their demise is seldom dated to the minute. Millerites, who predicted the end of the world in 1844 but were wrong, suffered the same fate.

William Miller was the one responsible for starting a religious movement. He completed the standard educational path after being born in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in 1782. There is no indication that he ever went on to receive formal education or training of any kind, yet even as a kid, he read voraciously. And he had plenty of opportunities as a young man to satisfy his need for knowledge by visiting numerous libraries.

Miller settled in the village of Poultney, Vermont, was married at age 21, and quickly rose to prominence among his peers there. He acted as a peacemaker in the community in addition to his other duties. He had a change of heart about religion after talking to many well-read folks in the neighborhood.

He was raised in a Baptist family but abandoned that faith during college and now considered himself a Deist. There, he still considered himself to be a believer, yet he was firm in his belief that the key to understanding God was rooted in reason rather than in the revelation found in the Bible. In light of his new beliefs, he no longer thought that miracles were signs from God. This was an outlook he would have to alter shortly.

Divine intervention

Miller, along with several other local males, went to New York State in 1812 to enlist in the United States Army to fight against the British. He was now exposed to the realities of battle. Miller’s fort was heavily bombarded by cannons during the 1814 Battle of Plattsburgh. Miller attributed his own survival to divine intervention when a shell landed near him, killing four troops and wounding two more.

Miller began to really contemplate the afterlife following the untimely deaths of his father and sister in 1815. He had second thoughts about his deism and started to read the Bible more intensively.

The Bible specifies the year of the end of the world

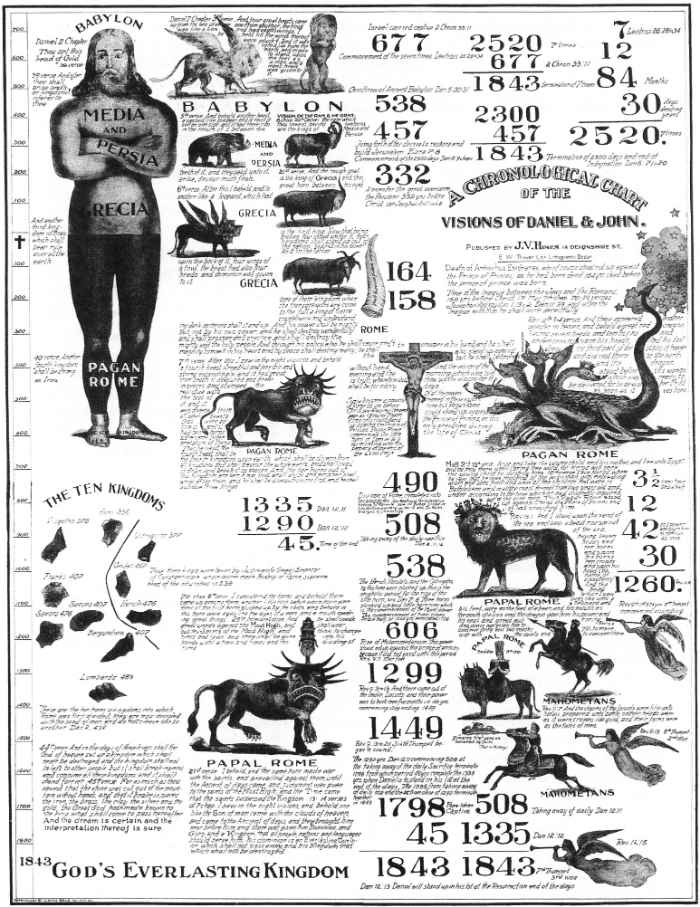

Miller drew one main conclusion from his reading of the Bible: the end of the world was near. Daniel 8:14 states: “He said to me, “It will take 2,300 evenings and mornings; then the sanctuary will be reconsecrated.”

Miller argued that the days in this passage should be read as years. Then Christ would return and cleanse the planet with fire. This meant that the end of the world was imminent, and it would come either before the year 1843 or in that year. 1822 had begun, so it wasn’t too far away.

But Miller waited nearly a decade before he started sharing his thoughts with the public. First proclaiming the end of the world to a small crowd in 1831, he submitted 16 pieces to the Baptist journal the “Vermont Telegraph” in 1832.

Since the end of the world was obviously not something that occurred daily, he was getting a lot of questions. Miller released a 64-page treatise in 1834 to save himself the trouble of personally responding to each inquiry about his beliefs.

The birth of Millerism

From now on, Miller’s ideas would be spread through an extensive publicity drive. A group of people in Boston, inspired by a clergyman named Joshua Vaughan Himes (1805–1895), worked to spread the word about Miller via a number of brand-new publications.

Numerous new magazines were published for various audiences in both the United States (especially in New York City) and Canada. Many of the 48 publications were short-lived, but they all helped to turn Miller’s ideas from a relatively unknown to a national religious movement.

Miller had an immediate obligation to his followers to provide them with a precise date for the end of the world. But he could only provide a window of time: from March 21, 1843, to March 21, 1844.

Kind of disappointing

On this day in 1843, however, nothing of note occurred. Without Jesus’ second coming, there would be no final judgment. Many believers, though, were not concerned since they believed the end of the world was still a year away. A more precise date, April 18, 1844, was determined after some further math. Then, nothing happened on that day again.

Therefore, Himes, the Boston preacher and Miller’s follower, conceded in a piece published in the “Advent Herald” on April 24 that he had perhaps overestimated a bit but that the end would really still come.

His argument was backed up by someone named Samuel S. Snow. The “Seventh Month Message” or “True Midnight Cry” was declared by this former skeptic—now a Millerite—in August 1844. The article introduced a brand new, unquestionably accurate date for the end of the world: October 22, 1844.

Miller’s followers continued to believe that the end of the world would occur on this day (it was a Tuesday) when the time was right. Despite the claims of Miller, Himes, and Snow, the only thing that vanished at the end of that day was the sun, which, in spite of their predictions, returned the next day.

The supporters are turning away

The fact that Miller’s predicted end of the world did not occur was very discouraging for many of his followers. Because most people had gotten rid of or sold their valuables in preparation for the end of the world.

Many farmers had stopped cultivating their land because they thought it was futile. But they were doomed to oblivion now. Miller lost the support of the vast majority of his followers after the “Great Disappointment,” as the incident came to be known, forced them to abandon him and his ideas.

However, Millerism did have repercussions outside the United States. On April 29, 1845, the “Albany Conference” convened, marking the coming together of the movement’s main members under the leadership of Himes and Miller. There, Miller’s ideas were again spelled out in detail and given a dogmatic stance. The Advent Christian Church was established as the offspring of the Evangelical Adventists after the conference.

A group that now numbers over 25,000 people in the United States alone. Another new religious movement developed in the wake of the “Great Disappointment,” and its members codified their beliefs in what is now known as the “Seventh-Day Adventist Doctrine.” Over 19 million people throughout the globe are currently part of it.

On December 20, 1849, Miller passed away, still believing that the end of the world was imminent. It was a fine ride nonetheless.