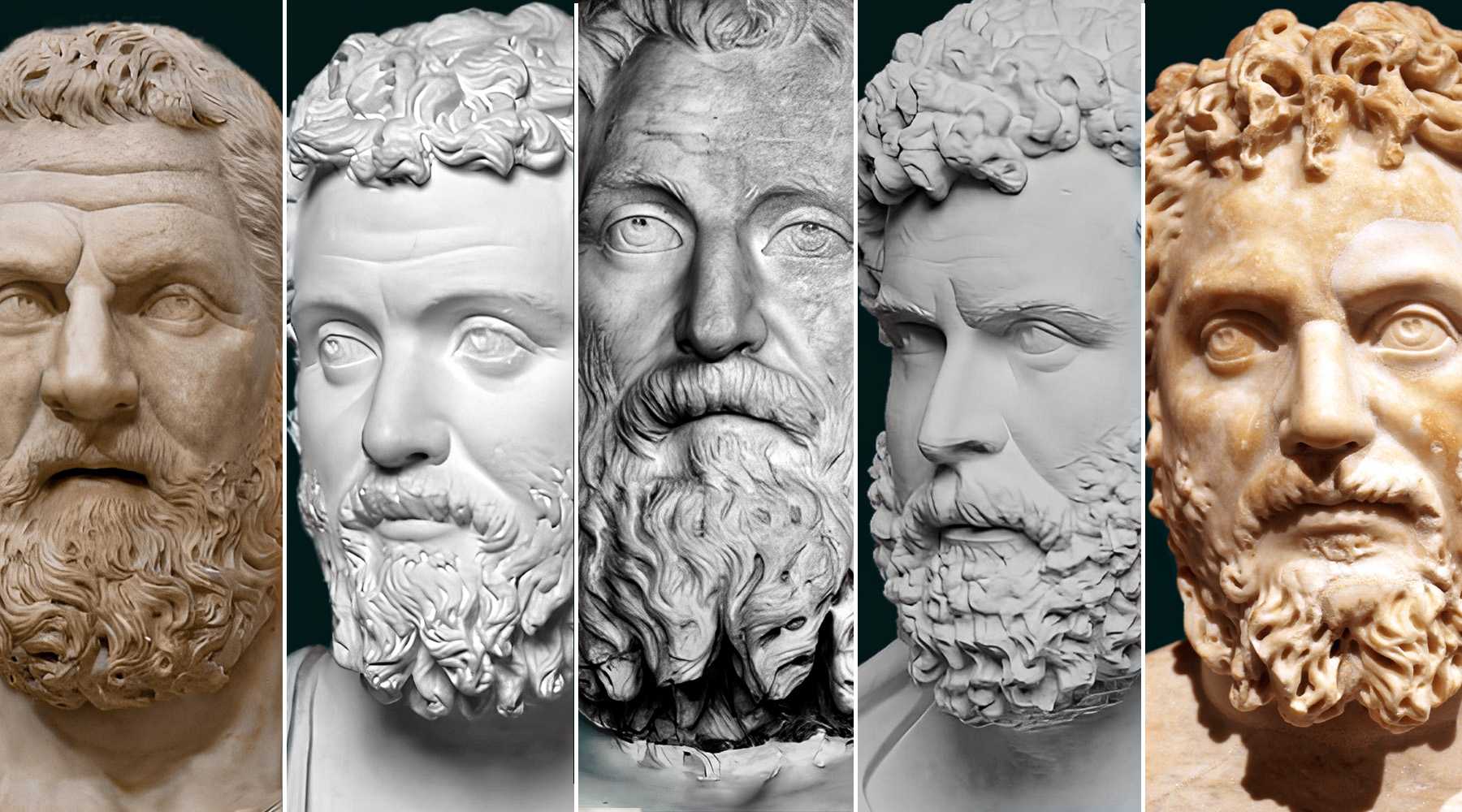

The Year of the Five Emperors refers to the year 193 during which five individuals claimed the throne after the death of Commodus on December 31, 192: Pertinax, Didius Julianus, Pescennius Niger, Clodius Albinus, and Septimius Severus.

This rapid succession of emperors begins with the assassination of Commodus on December 31, 192. Subsequently, Pertinax was selected by the Roman Senate and officially declared emperor on January 1, 193. Eager to implement reforms, the emperor encounters opposition from the Praetorian Guard and loses his life in a clash with the rebels after reigning for merely three months. His position is then assumed by Didius Julianus, who secures the throne solely through favors to the Praetorian Guard; however, he is toppled and executed on June 1st by Septimius Severus.

Septimius Severus’s Senate-appointed status as “caesar” triggers the resentment of Pescennius Niger, who proclaims himself as the emperor, sparking a civil war between Niger and Severus that engulfs the entire empire. In response, Severus forms an alliance with Clodius Albinus by designating him as “caesar,” directing their efforts against Niger. This conflict between the two contenders endures until 197. Eventually, Septimius Severus emerges victorious over both Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus, founding the Severan dynasty, which governs until 235, coinciding with the onset of the Crisis of the Third Century.

Year of the Five Emperors: Historical Background

The assassination of Emperor Commodus (reigned from 180 to 192) on December 31, 192, signifies the conclusion of the Antonine dynasty. It’s worth noting that the term “dynasty” is imprecise in this context. While Antoninus Pius wasn’t the dynasty’s inaugural emperor, the selection of emperors, apart from Commodus, was typically conducted through adoption, a customary practice within Rome’s upper echelons. A notable instance is Julius Caesar’s adoption of Octavian, who later became Emperor Augustus and himself adopted his successor, Tiberius.

The dynasty’s pioneer emperor, Nerva (reigned from 96 to 98), adopted a greatly respected military figure, Trajan (reigned from 98 to 117). Subsequently, Trajan, on his deathbed, adopted Hadrian (reigned from 117 to 138). Notably, Hadrian, who had no biological offspring, adopted Antoninus, a skilled governor from the province of Asia with a reputation for wise governance. Antoninus, in turn, agreed to adopt Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. The reign of Antoninus (reigned from 138 to 161) was distinguished by external and internal tranquility. He shared authority with the Senate and meticulously adhered to Roman traditions, leading the dynasty to be named after him.

Following his passing, his two adopted sons jointly ruled as emperors until Lucius Verus’ death in 169. Marcus Aurelius (reigned from 161 to 180) then became the sole emperor, but his reign marked the end of the peaceful era. He grappled with various conflicts against the Persians in the East and the Marcomanni, Quadi, and Sarmatian Iazyges in the West. He was the first of the dynasty to pass the throne to his biological son, Commodus (r. 180–192).

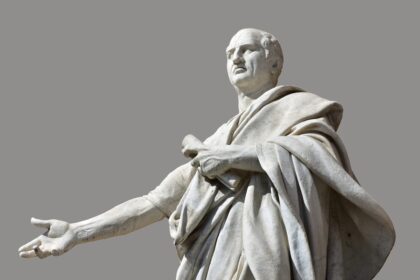

The first five emperors of the dynasty (Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius) were termed the “Five Good Emperors” by Machiavelli in his “Discourses on Livy,” a praise echoed by Edward Gibbon in his “The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”:

The vast extent of the Roman empire was governed by absolute power, under the guidance of virtue and wisdom.

Edward Gibbon , “The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”.

Nonetheless, the era of tranquility under their governance and the elevated principles characterizing their rule scarcely masked the dwindling economic activity and stagnant transportation, which triggered an economic, financial, and monetary crisis during Marcus Aurelius’ reign. The decline in municipal life, benefactions, supply shortages, and societal issues made this worse.

As the period neared its conclusion, conflicts on the Danubian frontier allowed the military to amplify its influence. Leaders from the equestrian class, rather than the senatorial class, increasingly saw the Roman Senate as remote and detached from their concerns. The uprising of Avidius Cassius, a usurper, in 175 upon learning of Marcus Aurelius’ death marked the outset of an era where the armies, particularly those in the East, sought to assert their leaders’ authority over the empire.

Pertinax

Publius Helvius Pertinax was born on August 1, 126, as documented in the Historia Augusta, in Alba Pompeia, located in Italy. He wasa born into a humble family. Through influential connections, he gained entry into the military, where he advanced in rank to become a cohort officer. He notably distinguished himself during the Roman-Parthian War from 161 to 166, which resulted in his rapid promotion to the esteemed role of procurator overseeing the province of Dacia.

Following a temporary hiatus during Marcus Aurelius’s reign, he was summoned back to duty to aid General Claudius Pompeianus in navigating the Marcomannic Wars. In the year 175, he attained the position of suffect consul in partnership with Didius Julianus and accompanied Marcus Aurelius on a journey to the Eastern regions. Subsequently, he capably governed the territories of Upper and Lower Moesia, Dacia, and Syria, culminating with his service in Britain.

Following Emperor Pertinax’s assassination by the Praetorian Guard in 193 AD, a power struggle and succession crisis were the main causes of the Year of the Five Emperors.

His final posting was as proconsul (188–189) in Africa prior to achieving the esteemed role of prefect of Rome, during which he was appointed as consul alongside Emperor Commodus.

In conjunction with Commodus’s mistress Martia and his chamberlain Eclectus, Praetorian Prefect Quintus Aemilius Laetus orchestrated a plot while serving as Rome’s Prefect to put an end to the emperor’s erratic behavior. Pertinax was led to the Praetorian Guard at the same time, where the Senate later approved his decision to hail him as the emperor after he promised a monetary reward.

Throughout his brief 87-day rule, Pertinax set forth a series of reforms aimed at reinstating an environment of liberty (rehabilitating citizens exiled during Commodus’s era) and economic stability (liquidating Commodus’s assets, reforming the denarius currency), which enabled him to fulfill half of the pledged monetary incentive. However, circumstances took a negative turn when he endeavored to restore discipline among the Praetorians, in line with his strict reputation. Early in March, while Pertinax was in Ostia inspecting grain shipments, the consul Quintus Sosius Falco orchestrated a preliminary attempt to overthrow him.

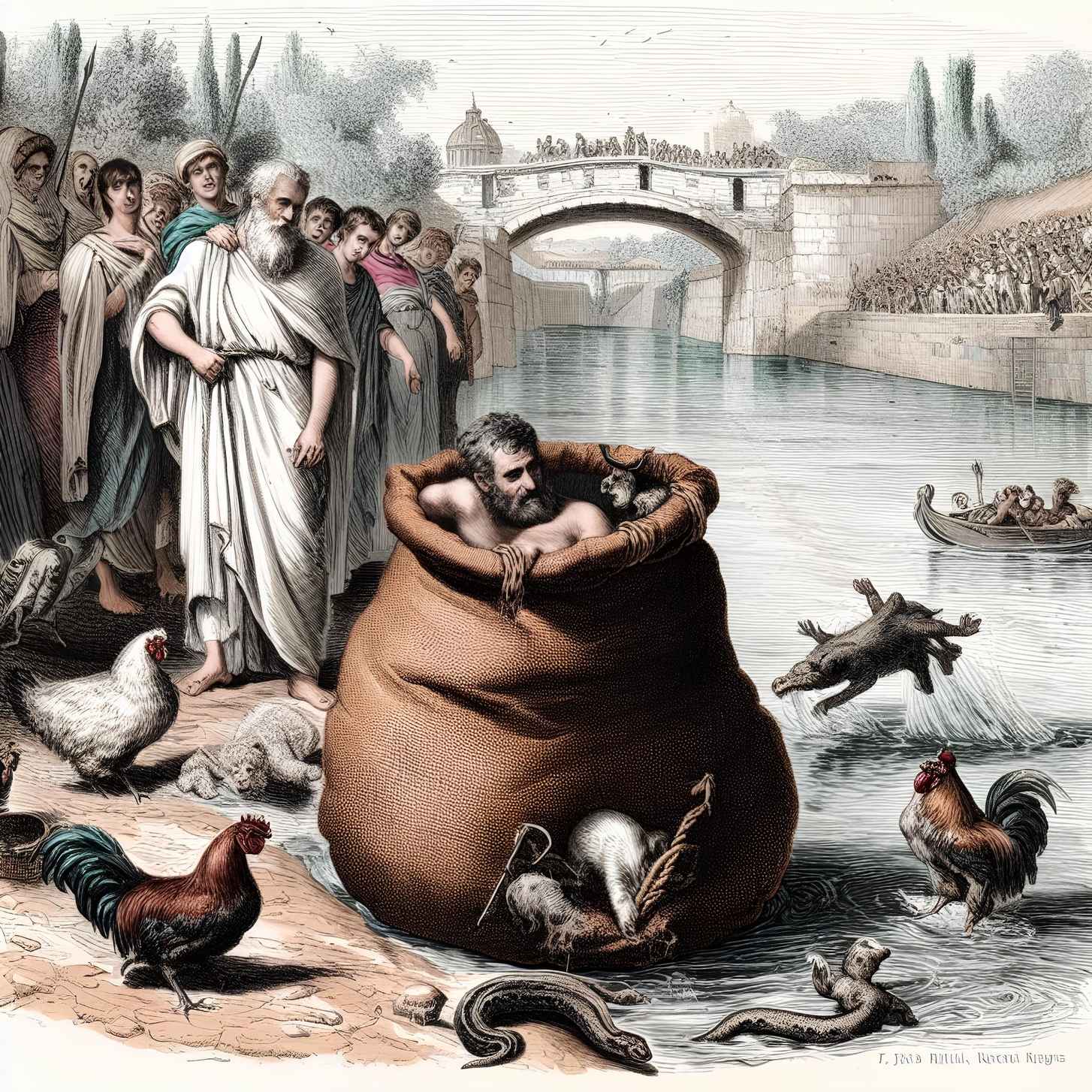

On the 28th of the same month, a contingent of Praetorians ranging from two hundred (according to Cassius Dio) to three hundred (Historia Augusta) stormed the imperial palace. In an effort to quell the situation, the emperor dispatched Prefect Laetius to mediate with them. Regrettably, Laetius chose to align himself with the mutineers, rendering the endeavor fruitless. Consequently, the emperor was assassinated and decapitated, with his severed head paraded to the Praetorian camp, sparking significant public outrage.

Didius Julianus

Marcus Didius Severus Julianus was born on January 29th, in the year 133 according to Cassius Dio, and 137 according to the Historia Augusta, into a wealthy family in Mediolanum (modern-day Milan). It’s possible that his parents passed away when he was quite young, as he was brought up in the household of Domitia Lucilla, who happened to be the mother of Marcus Aurelius. This connection to Lucilla paved the way for an early start to his political and military career, as these two spheres were often closely linked during that period.

Ascending to the position of quaestor before reaching the legal age, he progressively assumed roles as an aedile, praetor, and the legate of a proconsul in Africa and Achaea. Subsequently, he was appointed as the legate of the XXII Primigenia Legion stationed in Germania. In the year 170, he was dispatched to Belgium as a propraetor, where he spent five years effectively combating the Chauci and Chatti tribes. His successes culminated in his elevation to the rank of consul and his appointment as the governor of Dalmatia and Lower Germania.

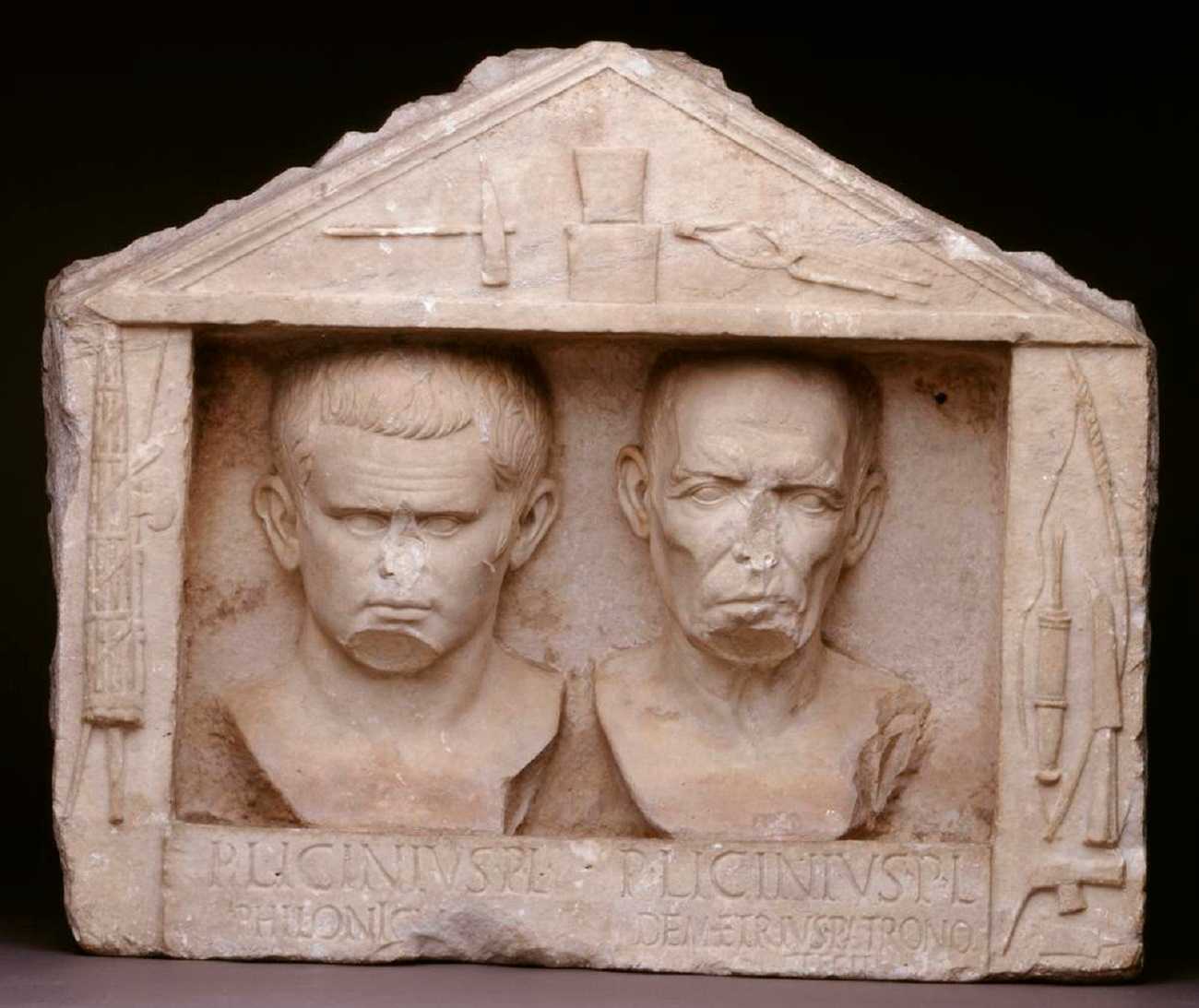

After the assassination of Pertinax, the Praetorian Guard auctioned off the position of emperor to the highest bidder, which led to Didius Julianus acquiring the title. However, his rule was short-lived.

However, his upward trajectory experienced an interruption, and he was summoned back to Rome to fulfill the role of “commissioner of provisions,” which involved the distribution of food to the less privileged. Some people think that Emperor Commodus’ worry about Julianus accumulating too much power was what led to this demotion. In fact, Didius Julianus was accused of conspiring against the emperor. However, not only did the jury declare him innocent, but it also punished his accusers.

Following his rehabilitation, he remained away from Rome. He was designated as the governor of Bithynia and subsequently, in the years 189 to 190, assumed the position of proconsul in Africa, succeeding Pertinax.

The assassination of Pertinax at the hands of members of the Praetorian Guard did not garner unanimous support within the guard itself. Views diverged regarding the selection of a successor. On that very day, the empire was essentially put up for sale: Sulpicianus, Didius Julianus’ father-in-law and the prefect of Rome at the time, offered each soldier 5,000 drachmas. However, Julianus managed to outbid him by proposing 6,250 drachmas. With their decision reached, the Praetorians led Julianus to the Senate, which had little choice but to validate the Praetorians’ determination.

However, the populace was not easily swayed. Julianus’ appointment was met with mockery in Rome and consternation in the provinces. Swiftly, three generals rebelled: Clodius Albinus in Britannia, Pescennius Niger in Syria, and Septimius Severus in Pannonia. The latter two rejected Julianus’ authority and declared themselves emperors. Septimius Severus, whose forces were in closest proximity to Rome, promptly advanced toward the city. Despite Julianus’ efforts, Severus seized the port and fleet of Ravenna. Julianus then proposed a power-sharing arrangement, but his proposal was futile. The ephemeral emperor soon found himself abandoned by all, including the Praetorian Guard that had initially championed him. On June 1st, 193, the Senate dethroned Julianus from his position and replaced him with Septimius Severus. The subsequent day saw Julianus sentenced to death, and a soldier assassinated him while he was in his bath. His reign lasted just slightly over two months.

Pescennius Niger

Born into an ancient family of the equestrian order around 135, Pescennius Niger is the first in his family to enter the senatorial order.

His military journey commences in 155 as a centurion primipile before ascending to the role of tribune. Around 172, he assumes the position of praefectus castrorum in Egypt, followed by the appointment as procurator ducenarius in Rome or Syria between 175-180, and subsequently as a legate in Dacia from 180-183. In 188, jointly with Septimius Severus, he partakes in quelling Maternus, whose factions spread terror across Gaul, Spain, and Italy. Finally, he secures the position of governor of Syria in 191, where he remains during the assassination of Pertinax.

Immediately, the three legions under his command rally to his side, and he sends an envoy to Rome to have his elevation recognized, but his messenger is intercepted by Septimius Severus. While Niger garners support from other Eastern legions, including the proconsul of Asia, Asellius Aemilianus, who occupies Byzantium in his name, Septimius Severus is already en route to Rome. He receives recognition from the Senate on June 1, 193.

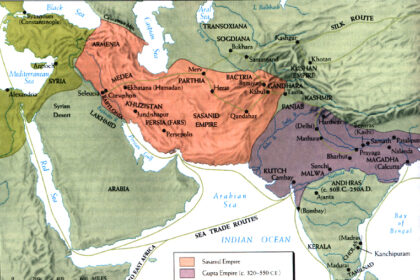

Subsequently, Pescennius Niger refuses to recognize Septimius Severus, prompting Severus to dispatch troops to Africa with the aim of obstructing Niger’s potential to sever the capital’s supply lines. He also takes the children of Niger and other governors of the East hostage. Nevertheless, the military forces are imbalanced: Niger commands merely six legions, whereas Septimius Severus wields the might of sixteen legions stationed along the Danube.

Considering the circumstances, Niger determines that an offensive approach is optimal. Consequently, he dispatches a contingent to Thrace, where they face defeat at the hands of Asellius Aemilianus. Despite this setback, Niger’s resolve remains unshaken as his forces lay siege to Byzantium. In a subsequent engagement occurring between November and December of 193, Aemilianus suffers defeat and meets his demise by beheading. This forces Niger to abandon the city and retreat to Nicaea.

A clash in late December 193 or early January 194 near Nicaea resulted in another defeat for Niger. Over time, the backing he once enjoyed in Asia dwindles, and by February 194, Egypt declares its allegiance to Septimius Severus.

In an attempt to evade the situation, Pescennius Niger endeavors to seek refuge with the Parthians. However, his flight concludes with his capture in late April 194, culminating in his execution by beheading. Subsequently, his severed head is dispatched to Byzantium, a city that remains steadfast in its refusal to surrender. The city’s resistance persists until July 196, when it ultimately capitulates following an arduous and protracted siege.

Septimius Severus will then have the city razed, but at the request of his son Caracalla, he will rebuild it a few years later due to its strategic importance.

Clodius Albinus

According to the Historia Augusta, Decimus Clodius Albinus was born on November 25, 147, in Hadrumetum (today Sousse in Tunisia), into a senatorial family from northern Italy that had been forced into exile in Africa due to reversals of fortune.

As per the Historia Augusta, he commenced his military career at a tender age. He reportedly took part in putting down the uprising against Marcus Aurelius in Bithynia by Avidius Cassius in 175, while commanding a legion. More reliable sources, like Herodian and Dio Cassius, report that he found himself stationed in Dacia around 180, alongside Pescennius Niger, before assuming the role of consul during the years 185–187. In recognition of his distinguished service, he later earned leadership positions in Gallia Belgica and later in Great Britain. In the latter, he dealt with unrest and insubordination among the three legions in the preceding years.

In the early months of 193, while stationed in Britain, he received news of the assassination of Pertinax and the subsequent rise of Didius Julianus. Similar to the actions of the troops under Pescennius Niger in Syria and those of Septimius Severus in Pannonia, the armies in Britain and Gaul rebelled and acclaimed Clodius Albinus as their emperor. However, he declined this title and formed an alliance with Septimius Severus, who had managed to seize Rome and gain approval from the Senate. Retaining considerable power, Clodius Albinus governed a substantial portion of the Western Roman territories, commanding three legions from Britain and the VII Gemina from Spain. Wanting to eliminate Pescennius Niger first, Septimius Severus allows his new ally to add the name “Septimus” and bestows the title of “Caesar” in April 193; the two men will share the consulship from January 1, 194.

Following the defeat of Pescennius Niger in the East, Septimius Severus opted to rid himself of this inconvenient ally. On December 15, 195, Clodius Albinus was designated as an enemy of the state, and Severus appointed his own son Caracalla to succeed him. With his options dwindling, Clodius Albinus proclaimed himself emperor either late in December or early in January 196. The provinces of Gaul, Spain, and Britain pledged their support to him. Crossing the English Channel with his legions, he established his base in Lyon. While he managed to overcome Severus’s legate and take control of the forces in Gaul, he struggled to rally the Rhine legions, which remained loyal to Septimius Severus.

Severus’s army advanced toward Clodius Albinus through the Jura mountains. The initial clash occurred at Tinurtium (Tournus), where Severus emerged victorious but without a decisive outcome. The ultimate showdown transpired in Lyon on February 19, 197. The result of the battle remained uncertain for a considerable period, ultimately culminating in Septimius Severus’s triumph.

Historical accounts from that time diverge on the specifics of Albinus’s demise during the battle. However, they concur that he met his end on or close to the battlefield, was decapitated, and his head was dispatched to Rome as a cautionary message to Severus’s adversaries. In addition, his family members, numerous supporters across Gaul and Spain, and senators who had sided with him in Rome faced execution. In response, the Senate enacted his “damnatio memoriae,” erasing his memory from official records.

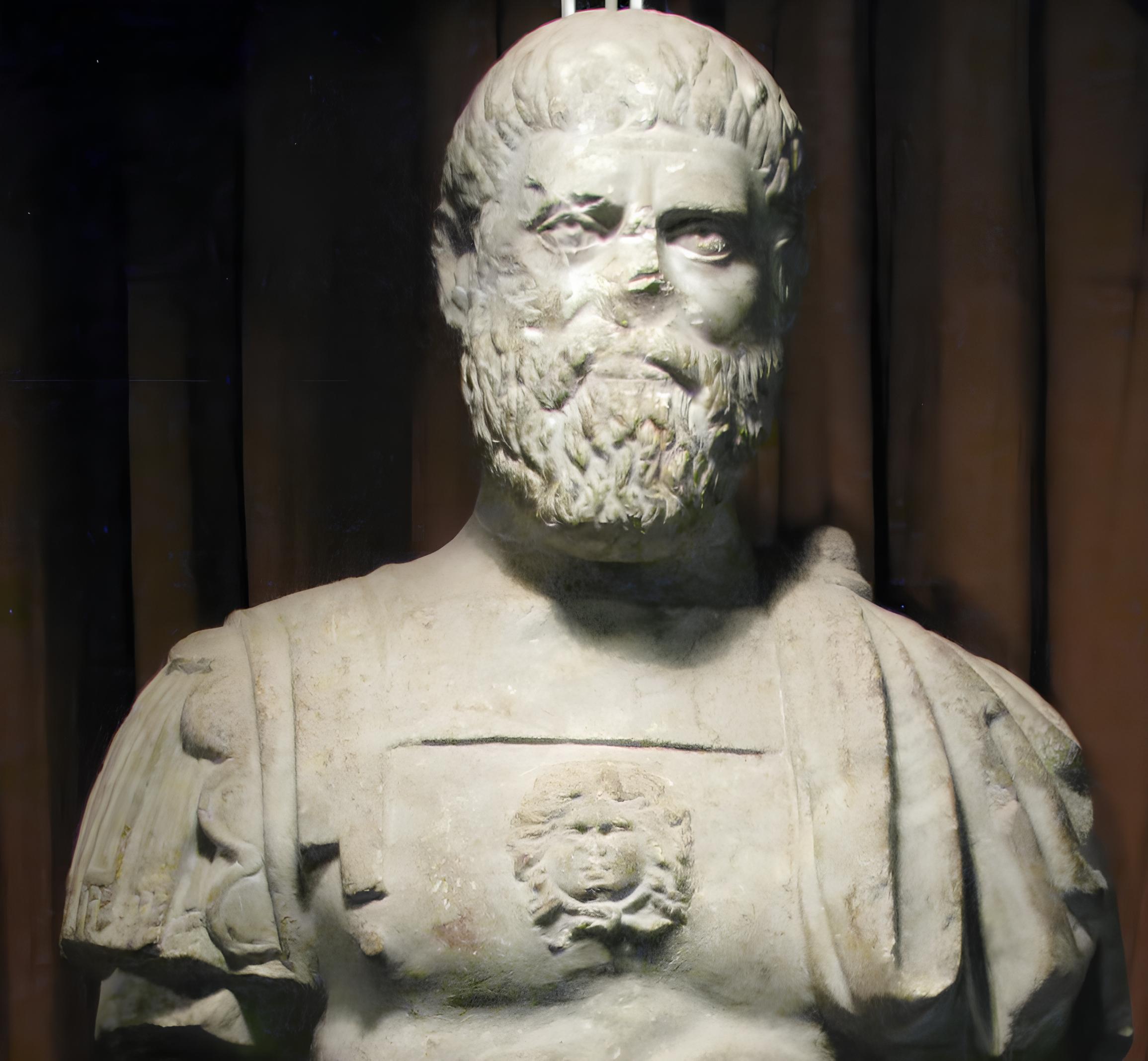

Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus Pertinax, born on April 11, 146, in Leptis Magna, which is known today as Al-Khums in Libya, was born into a family of significant local prominence and substantial landownership within the African province.

Thanks to an uncle, he gained the early privilege of joining the Senate, commencing a career in administration. He began as a quaestor in Sardinia in 171, served as a legate in Africa in 173/174, assumed the role of a tribune of the plebs in 174/175, held the position of praetor in 178, and became a legate in Spain in 179. However, it wasn’t until 182 or 183 that his genuine military journey began, with his promotion to lead the IV Scythica legion stationed in Syria. He faced Pescennius Niger between 186 and 188 while he was overseeing Lyon, a city he cleared of its outlaws.

Following a brief tenure as proconsul in Sicily in 189, he was assigned to Upper Pannonia the next year. It was at Carnutum, situated in modern-day Petronell-Bad, Austria, that he received news of Pertinax’s assassination on April 9, 193. Upon learning that the Praetorian Guard had essentially put the empire up for sale, his troops swiftly declared him emperor. Additional legions, such as the X Gemina, joined this proclamation, promptly supplying Septimius Severus with an army. With this force at his disposal, he embarked for Rome, confident in the support of political figures and senators from the African region. Despite efforts by Didius Julianus, who had replaced Pertinax, to organize resistance, he found himself abandoned, Rome opened its gates, and the Senate acknowledged Septimius Severus as the rightful emperor.

While concealing his disdain for the Roman populace and the senatorial aristocracy, he assured the Senate of his intent to govern in the tradition of Marcus Aurelius and Pertinax, both of whom he advocated for deification. He proceeded to disband the disgraced Praetorian Guard, responsible for selling the empire to the highest bidder, and replaced it with legionnaires, primarily drawn from the Danube region.

Following this, he initiated the elimination of his contenders. As previously mentioned, he gained the support of Clodius Albinus by appointing him as Caesar. He effectively dealt with Pescennius Niger in 194 during the Battle of Issus, subsequently campaigning against the Parthians, where remnants of Niger’s forces had taken refuge.

Building on this victory, he turned his attention to Clodius Albinus, nullifying his “Caesar” title by bestowing the same designation upon his son Bassianus, later known as Caracalla, signifying his ambition to establish a dynasty. To this end, in early 195, he asserted his lineage as the son of Marcus Aurelius and the brother of Commodus, forging a connection with the Antonine dynasty. It was during this time that Clodius Albinus, who held sway over a significant portion of the European provinces, declared himself Augustus. But the struggle was uneven, and Albinus would be eliminated the following year.

The Year of the Five Emperors highlighted the instability and fragmentation of the Roman Empire during the Crisis of the Third Century. It marked a period of civil war and demonstrated the challenges of succession in a vast and diverse empire.

Returning to Rome in June 197, he confronted opposition from the adherents of his two rivals, resorting to the execution of certain senators, the banishment of others, and the confiscation of their assets, which were then redirected to the imperial treasury. By the fall of 197, he formalized the dynastic principle by designating Caracalla as “imperator designatus” and his other son, Geta, as “Caesar.”

Nonetheless, another campaign beckoned, compelling him to depart Rome once again in 197–198, this time against the Parthians. This endeavor enabled Rome to reclaim Mesopotamia and the Parthian capital. Following this campaign, he ventured to the East, traveling along the Nile to its border with Ethiopia. Following a brief sojourn in Rome, he journeyed back to Africa, visiting several cities, including Carthage and his hometown, Leptis Magna. During this visit, he significantly extended the empire’s southern borders to fend off incursions from the surrounding tribes.

Between 205 and 208, he remained in Rome, engaging in a wide array of activities spanning the military, administrative, financial, urban planning, economic, and religious spheres.

Despite his waning health, he set off for Britain in 208 to combat the Caledonians, who persistently raided the two Roman provinces. It was here, in September-October 209, that he elevated his second son, Geta, to the status of Augustus. Thus, until his death, the empire had three emperors: an elderly one with declining health and two young ones who mutually hated each other.

He breathed his last at the age of sixty-five on February 4, 211, in Eburacum, known today as York. The dynasty he established witnessed the succession of five emperors from 193 to 235 AD, with a brief disruption between April 217 and June 218. Its conclusion came in 235, with the assassination of Severus Alexander, his final representative.