Starting on the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur, October 6, 1973, the Yom Kippur War was the fourth conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbors. The latter group took the initiative to regain the territory it had lost in 1967. After more than three weeks of hard fighting and significant casualties, the Israeli state finally managed to drive back its opponents. Although it was primarily a regional power struggle, the first oil shock and subsequent Western economic crisis were both directly attributable to this war. The Yom Kippur War was a high-intensity mechanized combat that served as a test case for a variety of military technologies and philosophies that are still in use today.

The Background of The Yom Kippur War

On June 10, 1967, when the Six-Day War finally ended, it looked like Israel had won. Its military was thought to be unstoppable when it crushed a pan-Arab alliance in a matter of days. As a result of Israeli control over the Sinai Peninsula, the Golan Heights, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip, Tel Aviv benefited from a protective glacis and more easily defended boundaries. Israeli officials were aware, however, that their principal Arab enemies (particularly Egypt and Syria) repudiated this status quo and vowed to regain their lands with pride. Thus, the area descended into an armed peace by the end of the 1960s, heralding the beginning of a new conflict. As a response, the Israeli side built up defensive fortifications, most notably the Bar Lev line on the eastern side of the Suez Canal.

Intense preparations were also being made in Damascus and Cairo for this next phase of the lengthy Arab-Israeli conflict. In the same way that the Israelis had access to a wealth of Western materiel, the Soviet Union supplied the tools and experts essential to the revitalization of the Arab forces. The Egyptians and Syrians received MIG-21 jets, T-55 and T-62 tanks, and, most importantly, hundreds of anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles. However, there was ambiguity and even contradiction in the computations of the various players.

Although the Soviet Union backed the Arab War effort (between 1967 and 1970, Israel and Egypt conducted a low-intensity war of attrition), it preferred to prevent an outright crisis from occurring. They were doubtful of the Arab nations’ prospects of victory and worked to preserve conditions that would allow them to keep their regional sway. The regime of Baathist and Alawite dictator Hafez-el Assad has regrouped in Damascus with an eye on retaking the Golan Heights. Cairo’s reasons were more nuanced than that.

Surprising to Israel

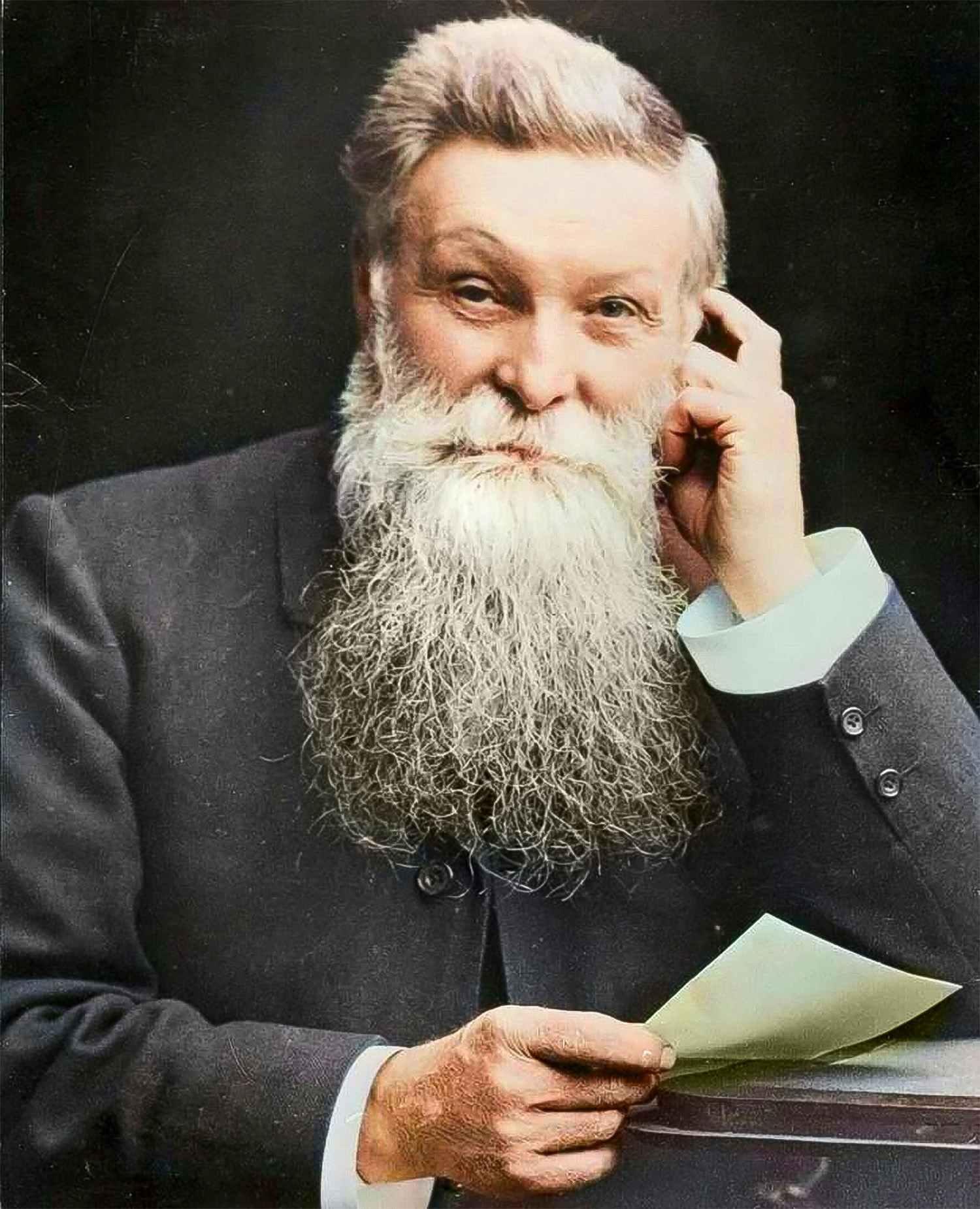

Nasser’s (now deceased) successor, Anwar Sadat, saw the depth of the political crisis brought on by the devastating 1967 loss. Sadat saw that Egypt was on the verge of collapse due to the country’s economic woes and the relative failure of a wide variety of Nasser’s initiatives. To counter it, he planned extensive, perhaps controversial measures. The new Egyptian leader, seeing that a pro-Western alignment would be more profitable than the Nasserite dalliance with Moscow, devised a fresh war against Israel as a means of extracting his nation from its current predicament. It wasn’t just about retaking the Sinai; doing so would give him the credibility to implement his ambitious domestic and international agendas.

The threat of a fresh Arab-Israeli confrontation did not make any of the superpowers pleased. The decision by OPEC to dramatically raise the price of a barrel of oil in 1973 only added to the concerns Nixon and Brezhnev already had about the potential economic fallout. Concerns were heightened by Israel’s de facto nuclearization.

Thus, in the summer of 1972, the Soviet Union and the United States publicly declared their agreement to end the war peacefully and keep things as they were. Cairo, whose war preparations were at a fever pitch, reacted immediately, with the Soviet military advisors leaving the country (although they remained in Syria). Over the course of the ensuing year, tensions rose steadily as both sides perfected their respective strategies for conflict. Both Moscow and Washington were powerless to prevent a disaster that had already begun to unfold.

Israel was supposedly taken by surprise by the Egyptian and Syrian assaults on October 6. Despite being initiated on a holiday, the IDF General Staff had been preparing for an Arab onslaught and the tools to counter it for quite some time. The inability of Israeli intelligence to predict the timing and tactics of the Arab attack was notable, however. The Israeli leadership was also suffering from the effects of a campaign of intoxication orchestrated by Cairo and Damascus, which had left them confused by the Egyptian and Syrian troops’ frequent moves.

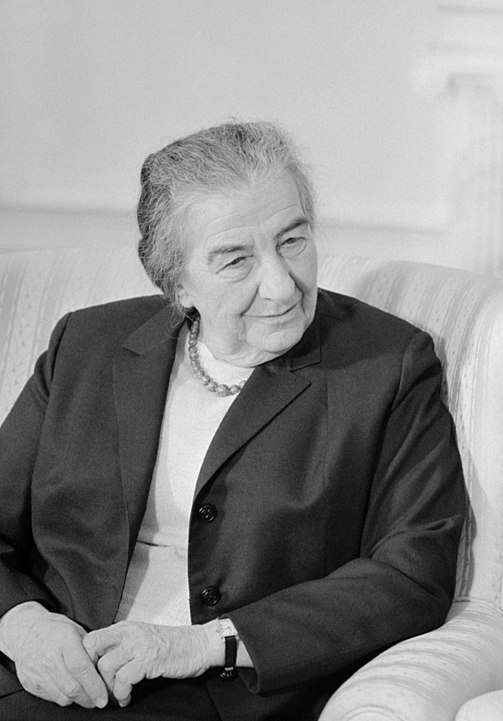

Tel Aviv felt the Arab nations were stalling for time until they could get their hands on some new Soviet weapons. With no more Soviet advisers, the Egyptian military was seen as weak (in reality, it had gained in quality, notably thanks to the purges of which the incompetent generals of 1967 were the victims). In addition, Prime Minister Golda Meir was afraid of alienating the U.S. and the West if she launched a second preventative assault, so she opted against doing so. Therefore, the Israeli army was in a precarious position, locked in a vise on two fronts, on the day of the 1973 Day of Atonement.

Yom Kippur War: The Sinai Front

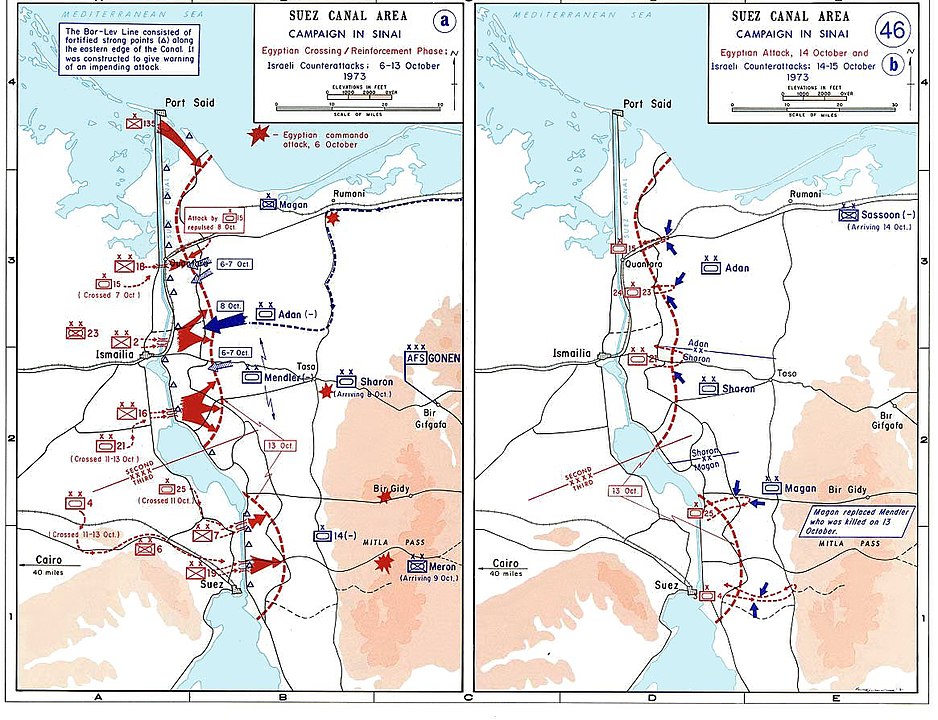

The Egyptian army, confident in its numerical advantage, began Operation Badr at two o’clock in the afternoon on the 6th of October, 1973, a holy day in the Jewish calendar. More than two hundred fighter jets pounded the Tsahal’s device in the Suez Canal area and southern Sinai with devastating firepower. In the far north, the Syrian army had begun its assault on the Golan Heights. The Syrians and Egyptians reflected long and hard on the debacle of 1967 before launching the Badr operation. The Egyptians, who believed that the Israelis’ air armament was their greatest strength, deployed a battery of SAM missiles to create a true anti-aircraft shield that was meant to protect the soldiers they planned to send into battle against the Bar-Lev line. Cairo sent an attack engineer armed with cutting-edge technology to break the Bar-Lev line (including water cannons designed to destroy the sandy flats developed by the Israelis). Last but not least, the Egyptian military, fearing an armored reaction from Tsahal, stocked up heavily on anti-tank missiles for its first-line soldiers (who had been without armored backup for about 12 hours).

Therefore, the IDF’s defense was somewhat weak when the eastern bank of the Suez Canal was attacked on October 6. When facing the Egyptian 2nd and 3rd armies, Israeli soldiers were forced to retire after losing air support and being attacked by daring helicopter commandos. In the early hours of October 7th, almost 850 armored vehicles from Egypt had already crossed the Suez Canal. Since Tel Aviv prioritized the Golan front, General Gonen (commander of the Sinai troops) was left to launch a counterattack with only his 162nd armored division (headed before the war by a certain Ariel Sharon).

The counterattack was a total defeat for the 162nd division and left the remaining Tsahal outposts on the Bar Lev line completely cut off from one another. The Egyptian infantry, bolstered by anti-tank missiles, displayed more resolve and skill than their 1967 counterparts. As it continued to advance into Sinai in the days that followed, it demonstrated this, although at a steep cost in lives.

The Israeli military’s humiliating loss at the Bar-Lev line did serve as a wake-up call. Eleazar, the Chief of Staff, pushed for a reorganization of the command that included the recall of active officers like Sharon. However, because of the situation’s improvement against the Syrians, Tsahal had been able to free up the troops needed for a counteroffensive. The U.S.-established air bridge allows for successful operation.

After the Israelis got over their first shock, they came up with a strategy to prove their tactical supremacy against the Egyptian army, which had already paid a heavy price for its early victories. Knowing how important the Egyptian anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles were, they organized infantry squads to eliminate them. Infantry and armored vehicle cooperation methods were evaluated and refined at the inter-army level.

Sadat insisted that the Egyptian army continue attacking the Tsahal lines on the 14th in order to relieve pressure on the Syrians. Even with a considerable number of additional tanks supporting the attack, it ultimately failed miserably. The failed strategy ultimately resulted in a head-on confrontation with strategically planned Israeli forces, which led to devastating casualties (more than 400 tanks destroyed in a single day, 10 times fewer for the Israelis). Response time from the Tsahal was quite rapid. Ariel Sharon’s 143rd armored division (reservists, reinforced by parachute forces) took advantage of a rift between the 2nd and 3rd Egyptian armies to establish a foothold on the African side of the canal (Operation Gazelle). Two other Israeli tank divisions operated concurrently to seal off escape routes for the Egyptians. Tel Aviv’s air force went all out for the fight when the anti-aircraft cover provided by the SAM missiles was substantially undermined.

The Egyptian Third Army was in danger of being encircled and decimated in the south of Sinai, but Sadat didn’t realize this until the 17th (with the assistance of satellite photographs given by the Soviets, who feared a catastrophic loss of Egypt). Israeli losses were not mitigated by Egypt’s sluggish and steady response (officers had trouble deviating from the initial, extremely tight plan). In the vicinity of Ismailia, Sharon encountered some light infantry and had trouble recovering the initiative.

That’s why Eleazar decided to do things at a slower pace so Egypt could send in its last remaining armored reserves. The Israelis were barely able to hold them back during their last push on the 23rd. The weapons finally quieted with the leading troops of Tsahal within a hundred kilometers of Cairo and 75,000 Egyptian soldiers trapped on the opposite side of the Suez Canal.

And the Golan front

Starting on October 6th, the Syrian army sent a large force to the Golan Heights. In this battle, five divisions backed by heavy artillery and aircraft faced off against just two Israeli brigades. However, the Syrians faced challenges on several fronts. To begin with, the rough and segmented landscape in which the battle took place favored the defenders. Second, even if Israel were willing to cede territory in the Sinai, it would still place the utmost importance on retaining command over the Golan Heights. To be sure, if the Syrians were to take it, they’d have a commanding vantage point over the surrounding plains and the three main cities of Haifa, Netanya, and Tel Aviv. For this reason, the Golan front was prioritized above the Sinai front for the deployment of reinforcements and reserve forces.

The Syrians had some success against the enemy for two days, but it came at a high cost, mainly in the form of tank casualties. Two IDF brigades were originally involved in the battle, and they gave their lives so that the reserve units could advance (often transported by helicopter). The Damascus forces were unable to break off the plateau despite seizing Mount Hermon, whose monitoring station was a major factor. With the support of three divisions (two of which were armored), the Israelis launched a counteroffensive on the 8th, and by the 10th, they had returned to their pre-war positions.

The Israeli leadership chose to press its advantage over the Syrians after a furious discussion (Gonen’s failures in the Sinai were on everyone’s mind). Although this may have had negative military consequences, it was ultimately a political decision to seize enemy territory in preparation for negotiations (at that time, an Egyptian defeat in the Sinai was still a distant prospect). Tsahal maintained its assault on the Syrians from the 11th to the 14th. When the Damascene army was overrun, they fled quickly and only after making heavy casualties did they succeed in stabilizing the front (and thanks to the help of foreign units, but we would come back to this later). By day 10, Israeli forces had advanced 40 kilometers from Damascus, a result that pleased Tel Aviv. Israeli forces were pleased with this outcome and did not launch any more offensive operations on this front (apart from the retaking of Mount Hermon) until the truce.

An Internationalized Conflict

The Yom Kippur War was first seen as a confrontation that included more than just Israel, Syria, and Egypt. To begin with, it was a turning point in the ongoing conflict between Israel and the Arab world, which sparked new initiatives and new emotions among Muslims. Since this was the case, Damascus and Cairo could rely on the backing of Saudi Arabia and Kuwait in terms of both money and supplies (the equivalent of a brigade and large sums of money). Algeria, Morocco, and Libya all deployed aviation units to Egypt (with Algeria also sending an armored division that arrived at the front too late). On Sadat’s side, a battalion of Palestinian fighters was also there. Both Pakistan and Bangladesh were satisfied with the mostly medical assistance they received. The assistance of the Jordanians and, more importantly, the assistance of the Iraqis (two armored divisions) helped Syria halt the Tsahal attack in mid-October.

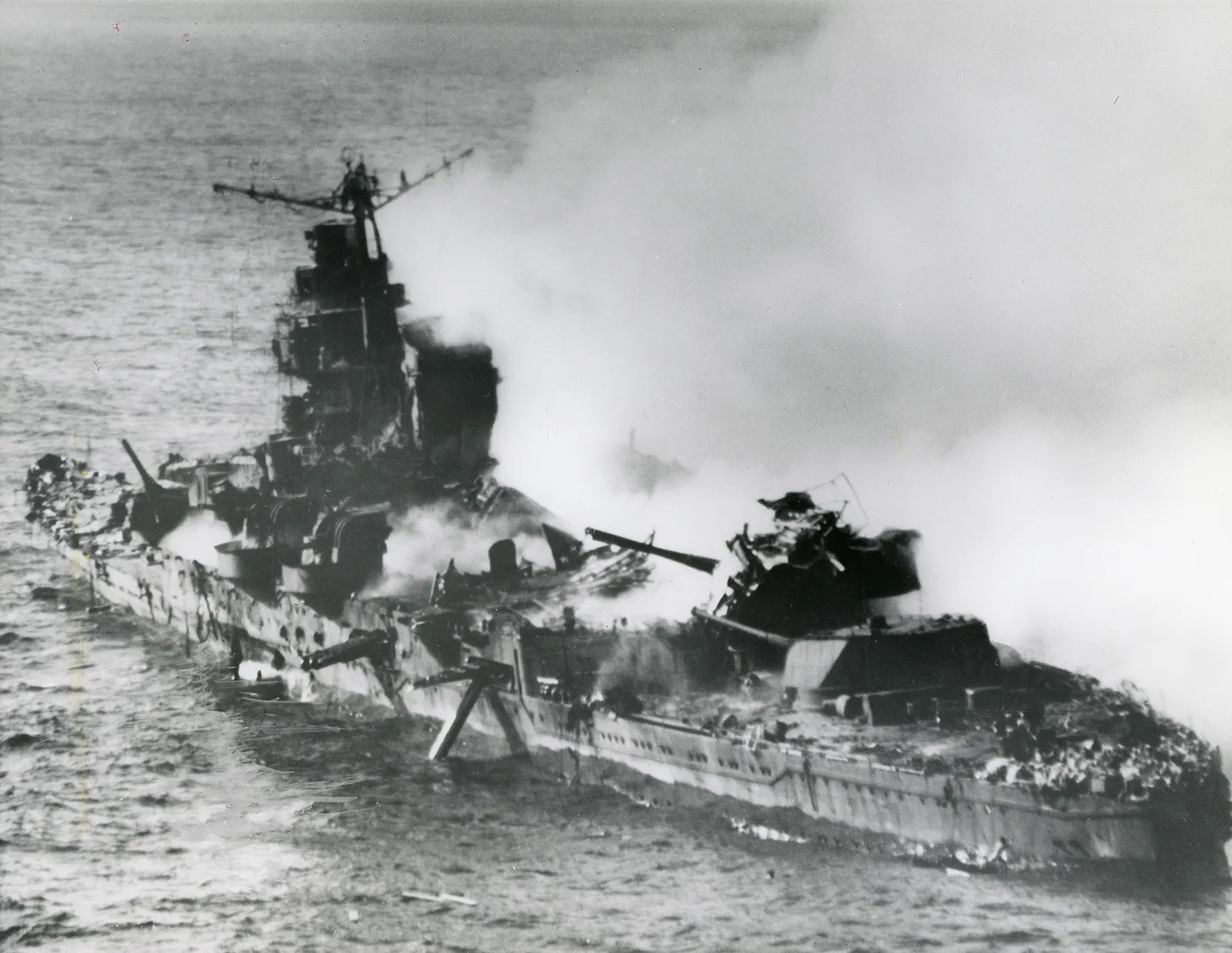

However, the role of the two Cold War superpowers in the struggle cannot be overlooked. The Soviet Union was against Sadat and Assad going to war, but once it had begun, they had to back them up. In spite of the stunning victory of the Israeli navy, which destroyed the Syrians near Latakia on the 7th and the Egyptians at Damietta on the 8th and 9th, Moscow resumed supplying Syria and, to a lesser degree, Egypt (often through Libyan ports) beginning on the 9th. In under three weeks, nearly 400 tanks and a considerable quantity of spare parts, ammo, etc. were sent to Damascus. Furthermore, occasionally there was direct military help from USSR allies like Cuba and North Korea.

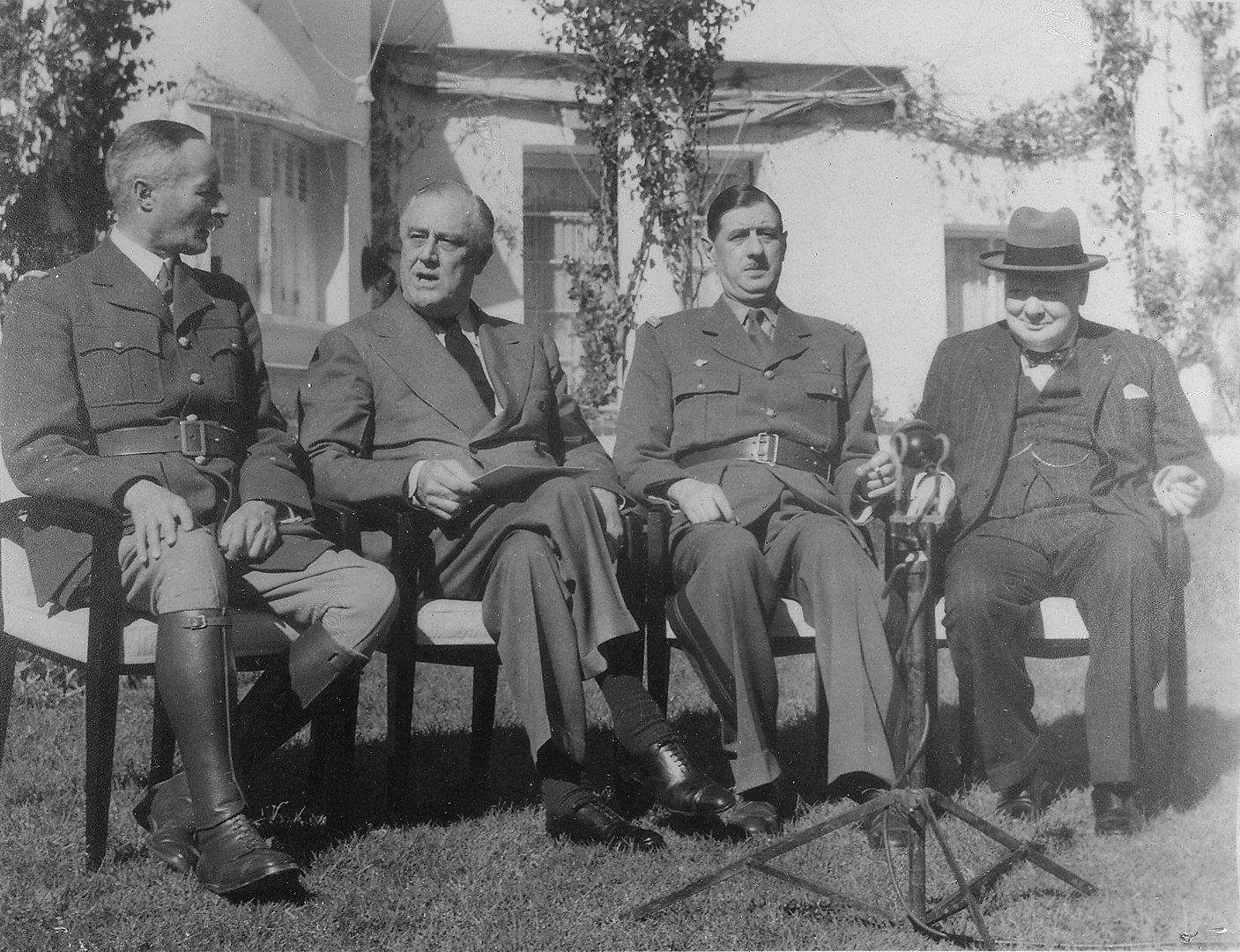

However, the aid the United States provided Israel throughout the war was just as crucial. Tel Aviv deftly exerted pressure on Washington by purportedly activating the plan to deploy nuclear weapons in the deadliest hours of the battle (and in particular on October 7, 8, and 9). After the Watergate scandal, the goal was to convince a weak President Nixon (who was influenced by Henry Kissinger) of how bad things were.

The United States decided to offer major help to Israel to compensate for its losses in the early going because it feared, above all else, that the fight would become nuclearized. A massive air bridge (Operation Nickel Grass) was established with additional support from the navy. Tsahal offensives were fueled and equipment stocks were replenished thanks to the thousands of tons provided in this manner.

Russia and the United States both provided the troops of its clients and friends, but they were united in their belief that the struggle may bring them to extremes they desperately wanted to avoid. Therefore, on October 22, the United Nations unanimously supported a resolution (Resolution 388) that called for an end to hostilities. The Soviets placed their armed forces on nuclear alert when it seemed like the Israelis were ignoring it to extend their advantage in Egypt, sending the United States National Security Council into a state of fear.

On October 25, in response to intense American pressure, Israel agreed to a ceasefire. On October 28th, after some hiccups, the truce finally went into force. When it came down to it, the superpowers’ well-established interests were more pressing than the problems in the Middle East.

Lessons and Results of The Yom Kippur War

One of the most violent mechanized confrontations in the post-World War II period was the fourth Arab-Israeli war, which lasted for just a month. The material destruction was unprecedented and a testament to the effectiveness of today’s weapons. More than 400 planes were shot down (including about a hundred Israeli aircraft), and about 2,500 tanks were destroyed, most of them on the Syrian-Egyptian border. In human terms, the losses amounted to 30,000 men on the Arab side (about 10,000 dead), 11,000 on the Israeli side (about 3000 dead).

The battles restored the infantry’s standing through combined tactics and cooperation with armor. Moreover, they demonstrated the significance of cutting-edge anti-tank and anti-aircraft capabilities, which helped put the tank-aircraft tandem in context. In the end, they elevated the significance of intelligence agencies and special forces.

From the perspective of the Arabs, and notably Egypt, Israel’s current predicament was seen as a win since it was the worst it had been since 1948. Despite Egypt’s military defeat, Sadat was able to win the popular support he needed to remain in office (with the notable exception of the Islamists, which will be fatal to him). Egypt was once again at the head of the Arab world, giving it the leverage to deal with an uncertain Israel.

The Yom Kippur War was a crushing defeat for the Hebrew state. The idea of the Tsahal’s invincibility was seriously damaged, as was the myth of the infallibility of the intelligence agencies. As a result of the subsequent political crisis, the Labor Party lost power and was replaced by the Likud, a new right-wing party, in 1977. And there was a serious moral examination of Israel as a country, with secular Zionism giving way to religious influence. Israel was lost and confused, and it felt alone on the world stage after its relationship with Washington was strained.

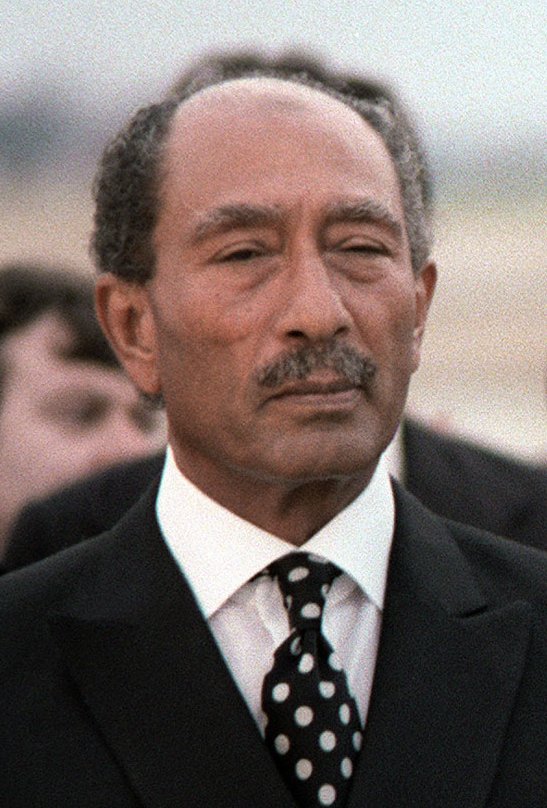

Because of this, it’s not surprising that the Israeli-Egyptian disagreement was quickly resolved. With his confidence restored by his victory in 1973, Sadat approached the Likud administration of Menachem Begin for bilateral discussions in 1977. Both Cairo and Tel Aviv saw this as a chance to make a gesture to Washington while also putting an end to an expensive conflict. The Camp David Accords, signed two years later, marked the beginning of a path to peace between Israel and Egypt, and the eventual transfer of the Sinai Peninsula to the latter.

It didn’t last long for Sadat to celebrate his victory. When the Egyptian president continued to criticize his former friends (most notably Syria, which maintained its resistance to Washington), Syria and the rest of the Arab League expelled Egypt. On the anniversary of the launch of Operation Badr, October 6, 1981, he was murdered by Islamist troops who were furious with his pro-American about-face and the peace he had made with Israel.

Bibliography:

- Gordon, Shmuel L. (2000). “The Air Force and the Yom Kippur War: New Lessons”. In Kumaraswamy, P. R. (ed.). Revisiting the Yom Kippur War. London: Frank Cass Publishers. p. 231. ISBN 9781136328886.

- Dunstan, Simon (2007). The Yom Kippur War: The Arab-Israeli War of 1973. ISBN 9781846032882.

- Rodman, David. Israel in the 1973 Yom Kippur War: Diplomacy, Battle and Lessons (Sussex Academic Press, 2016).

- Herzog, Chaim (2003) [1975]. The War of Atonement: The Inside Story of the Yom Kippur War. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-85367-569-0.

- Herzog, Chaim (1982). the Arab-Israeli Wars. Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-50379-0.