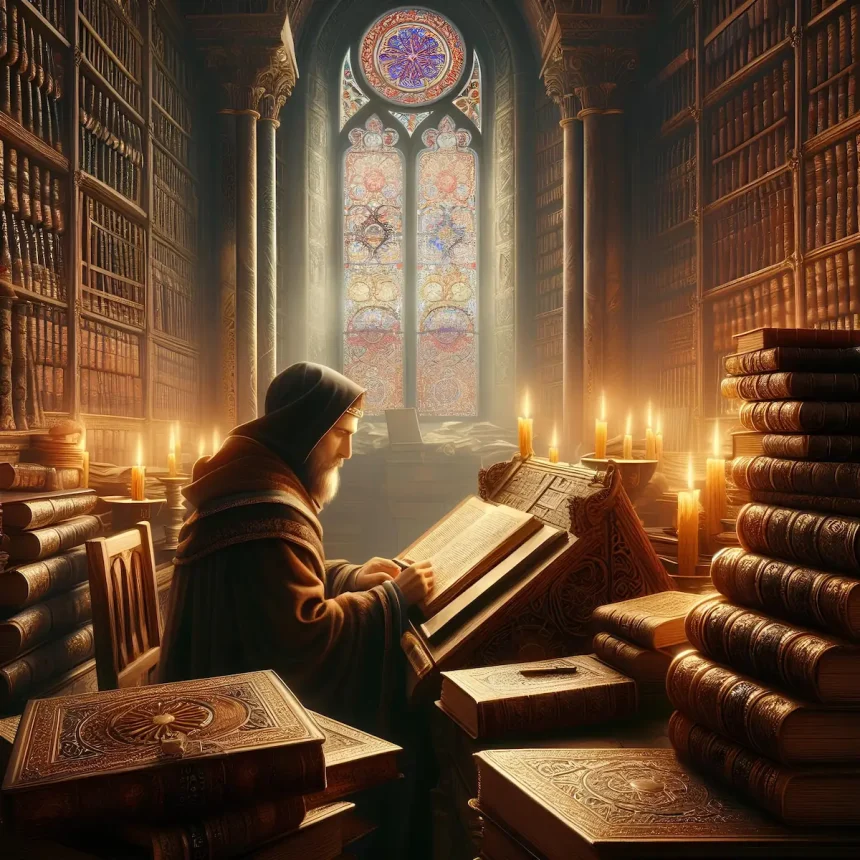

If infantry continues to use javelins and pikes, literature like epic poems, plays, and novels extolling chivalric life frequently mentions the knight’s lance. This lance, equipped with a. During the Middle Ages, books were primarily the labor of monk scribes, tasked with transcribing manuscripts. The scribe initially prepares the parchment by drawing lines and reserving margins and spaces for illumination.

These illuminations, found within the works, serve more than just decorative purposes; they often have precise functions, aiding in the comprehension of the text for those unable to read. Most works comprise excerpts from the Bible, liturgical texts, or copies of classical works. They feature wooden covers, frequently reinforced with metal, and are fastened together with clasps. Alternatively, some are bound with leather covers, occasionally embellished with gold and silver, enamels, and precious stones.

Books in the Middle Ages

It is necessary to keep in mind that the vast majority of men and women in the Middle Ages could not read and did not have the material means to access culture, which was the prerogative of wealthy lords and ecclesiastics. The book then served as a support for the monk’s sacred meditation on scriptures, as entertainment for princes in the form of novels or hunting treaties, and later as a tool for diligent students struggling with a Latin grammar manual. The book is not only a text that takes increasingly varied forms but also a fabulous repertoire of images.

The illustration of devotional books or secular works acquired particular importance during this period: the image accompanies and enriches the text, with the greatest artists participating in the decoration of manuscripts. Painting is in the books!

The history of the book evolved significantly before reaching its definitive form in the Middle Ages. This history fits between two major technical developments: the appearance of the codex in the first century BC and the invention of printing around 1460. In antiquity, writing materials were as varied as they were ingenious: wooden tablets coated with wax, clay tablets, tree bark, silk fabric strips in China, and papyrus scrolls in Egypt, Greece, or Rome. These materials remained in use for writing ephemeral documents, such as the “beresty” rough drafts scribbled on birch bark by Russian merchants.

Writing Materials in the Middle Ages

What were the three main writing materials in the Middle Ages? Papyrus, parchment, and paper. Papyrus, associated with ancient Egypt, from which it originates, remained widely used in the Mediterranean world, particularly by the pontifical chancellery. Around 1051, it was supplanted by parchment (which takes its name from the city of Pergamon in Asia Minor). It spread during the 3rd and 4th centuries due to technical improvements. All kinds of animals could provide skins for their production; goats and sheep produce an ordinary quality called “basane.” Calfskin yields “vellum,” a fine and prized quality but also the most expensive.

The parchment makers settled in cities or near monasteries. The production of parchment is long and meticulous. The skins are sold in bundles, folded in two or four (the fold determines the formats). They can be dyed red or black, with gold or silver letters for luxury manuscripts. The skin is stronger and more resistant to fire; it can be used for bindings or scraped and rewritten.

Paper, which appeared at the end of the Middle Ages, was invented in China around 105 AD, and its dissemination followed the Silk Road. Made from rags soaked in a lime bath, it consists of crossed fibers and stretched-on frames. The use of the paper mill and the press improved its technique. The paper eventually became popular due to its very competitive price (thirteen times cheaper than parchment in the 15th century).

Writings intended to last were transcribed on scrolls of papyrus or parchment. The appearance of the codex (a book of parallelepiped shape mentioned around 84–86 AD) quickly became a real success. More practical than the scroll, it allows writing on a table or desk. Bibles in the form of codices are mentioned as early as the 2nd century.

The Scribes and Their Tools

The scribe is a great specialist in writing, which is a slow and tedious task. They practice on wax tablets that they engrave using a metal, bone, or ivory stylus. To trace their letters on parchment or paper, they have three essential tools: the stylus, a lead, silver, or tin mine used for drafts and drawing lines to present homogeneous pages; the “calamus” (cut reed); and finally, the bird feather pen.

Duck, raven, swan, vulture, or pelican feathers are used for writing, with the best being the goose feather! The scribe cuts the feather with a knife. Strong rhythms, emphasized verticals and finer horizontals, and alternations of full and thin strokes are determined by the cut.

Black ink is obtained by boiling plant substances such as gall nuts and adding lead or iron sulfates.

Red ink is reserved for the titles of works and chapters (this custom gave its name to “rubrics,” a term derived from the Latin “ruber,” meaning red). In the absence of a table of contents, they allow the reader to navigate the manuscript more quickly. It can be divided into sections and distributed to several scribes who share the work to speed up copying.

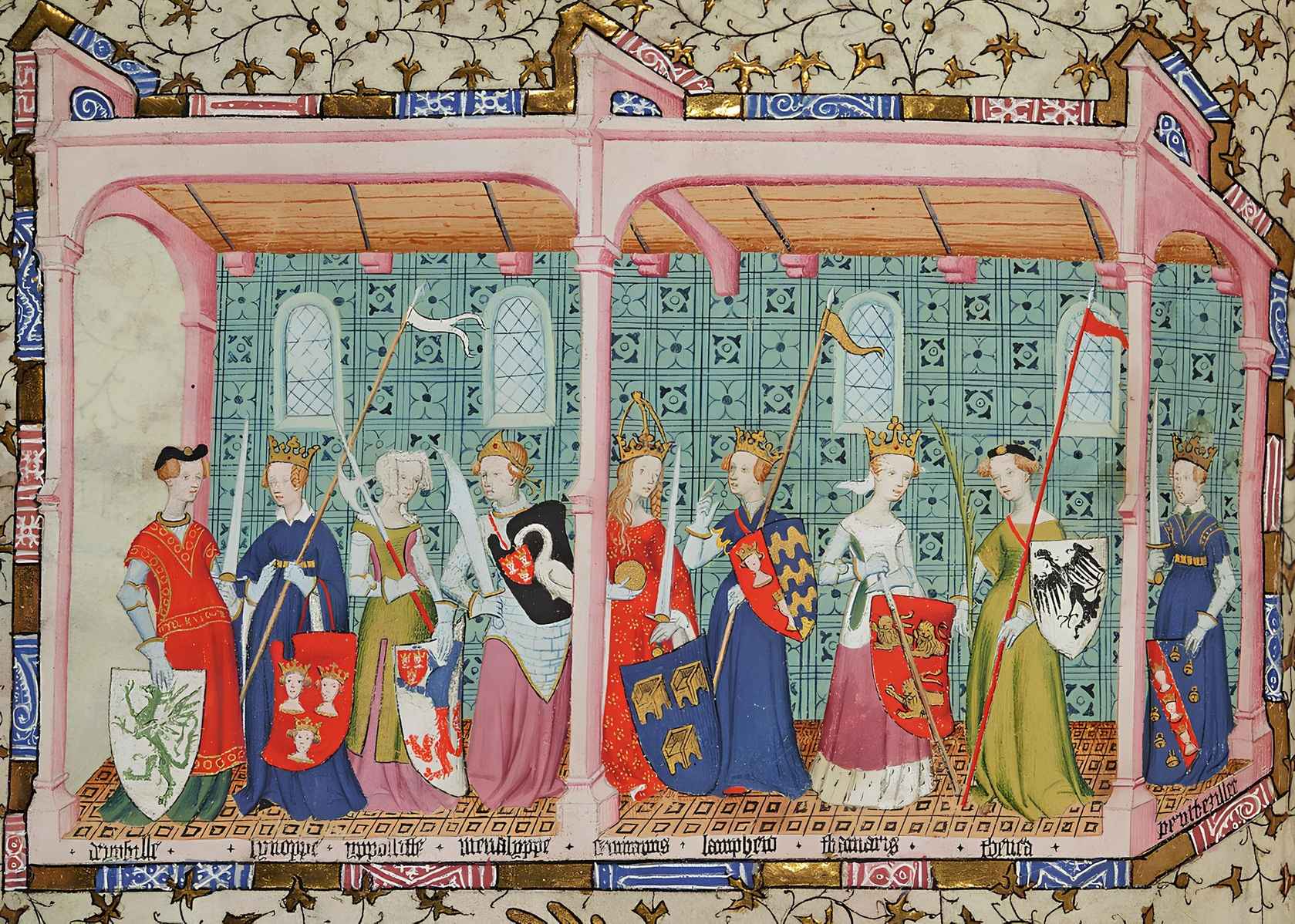

Illuminations and Miniatures in Medieval Books

The works with illustrations are rare due to their high costs. Illumination serves a dual function: decorative, enhancing the work, and pedagogical, shedding light on the text. The illuminator receives a sheet of parchment already written on it, with spaces delineated by the scribe for painting. Several hands contribute to the manuscript’s decoration: the illuminator of letters, the one of borders, and the “historian” or painter of history who creates the illustrated scenes.

Note

Illumination refers to the decorative elements found in medieval manuscripts, including elaborate borders, initials, and illustrations. These illuminations were often embellished with vibrant colors, gold leaf, and intricate designs.

During the Romanesque period (11th and 12th centuries), capital letters could also serve as frames for genuine compositions, with the ascenders of the initial letter allowing the decoration to develop. In the 14th century, margins became populated with vegetal motifs, acanthus leaves or flower bouquets, real or fantastical animals, characters, coats of arms, and sometimes small scenes in medallions.

The goose feather is the main tool of illuminators. It is cut with a knife, and the width of its flat end determines the line’s width. Pointed reeds, called calamus, are also used. The knife is used to cut feathers or scrape the parchment.

The illuminator uses pigments to paint manuscripts. Some, like red, brown, or yellow ochres, are simple earth pigments. Others, such as orange, red, or brown, come from natural metal deposits.

Some are extracted from stones, such as lapis lazuli, which is blue.

White is obtained from chalk, lead, or bird bone ashes. The illuminator grinds the pigments into powder, then fixes them on the parchment with glair and beaten egg white. The drawing is traced with a dry point and then inked over. In luxury manuscripts, illuminations are highlighted with gold. Gold powder, mixed with glue, is applied to the parchment and carefully polished.

From Monasteries to Urban Workshops

Concentrated in monasteries during the early centuries, manuscripts (produced in a workshop called a scriptorium) established themselves in cities, giving rise to a genuine book market. Punctuation and word separation appeared in Northern France in the middle of the 11th century, along with the practice of silent reading. Episcopal schools, desired by Charlemagne, developed during the 12th century simultaneously with the growth of cities. Booksellers emerged in the early 13th century; they commissioned manuscripts from scribes and sold them to schoolmasters and the university.

Note

A scriptorium was a dedicated room or area within a monastery or scriptorium where scribes worked on copying manuscripts. It was typically equipped with writing desks, parchment, ink, and other tools necessary for manuscript production.

Booksellers, or stationers, dominated the four trades related to book production: scribes, parchment makers, illuminators, and binders. While the first libraries appeared in monasteries, they later became public or private.

Even if they were not illuminated, books were expensive. After purchasing parchment, one had to pay for copying, a slow and tedious task, and then for binding. Some improvements in manufacturing toward the end of the Middle Ages helped reduce the cost of books: smaller formats, the use of paper, simplification of decoration, and more modest bindings. Booksellers also offered second-hand books.

University Books

A new readership emerged as a result of the expansion of urban schools in the 12th century and the establishment of universities in the following century. Masters and students alike considered books to be the primary tools of knowledge. Not particularly wealthy, intellectuals of the Middle Ages managed to possess fundamental works; some even assembled a small private library, but most settled for second-hand copies or copied borrowed manuscripts.

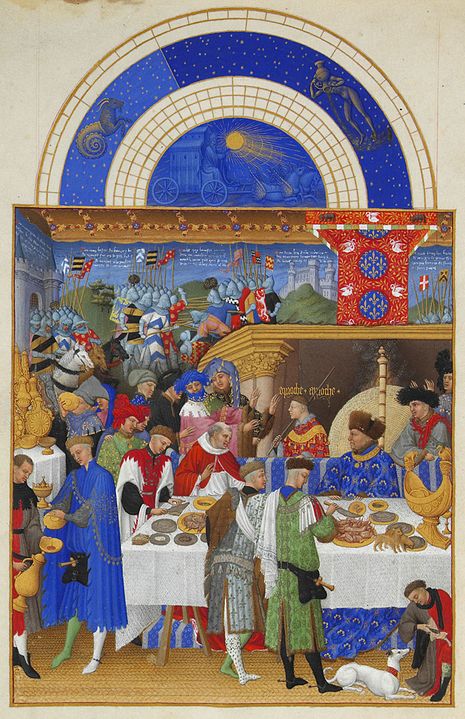

The most well-known collection of university books is that founded by Robert de Sorbon (confessor of Louis IX in 1250) for poor students destined for theological studies at the University of Paris (about a thousand volumes). The diversity of images, the richness and whimsy of the decorations, and the world of unalterable colors that time and wear could not tarnish are all elements that explain the fascination that medieval books exert on us.

The distance separating us from their creation and their miraculous preservation make them almost sacred objects, zealously kept by libraries or private collectors. Occasionally, some exhibitions reveal to a dazzled public the richness of this heritage. These works have indelibly marked our vision for this period.

From the elegance and fantasy of the “Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry” to the imagination of the “Mozarabic Apocalypses” and Romanesque bibles, all medieval manuscripts introduce us to a dream world as they did centuries ago to their first readers.

University works focused on theology, law, or medicine, while kings, princes, and lords collected volumes dedicated to religious and moral edification, political knowledge, and entertainment (novels, poetry).