In Sweden, Christmas is a time to celebrate the birth of Christ, a tradition that has its origins in the ancient pagan festival of “Jul” and which has evolved via Christian (especially Lutheran) traditions as well as more contemporary, indigenous, and international practices. Compared to previous centuries, its religious aspects have taken a back seat in modern observance, which has been somewhat watered down, secularized, and commercialized.

-> See also: 48 Countries That Celebrate Christmas Widely

Advent candle holders and children’s “Christmas” calendars serve as indoor heralds of the impending holidays, while Christmas decorations decorate store windows and sidewalks. Candles, table runners, miniature carpets, gnomes, angels, and gingerbread houses are the festive decorations that are put up in homes in the days leading up to Christmas in Sweden. Green wreaths fashioned from lingonberry or pine branches are often draped over entryways.

Christmas Eve, December 24th, is the most important day of the year in Scandinavian nations, which is a unique tradition. On this day, guests gather for Christmas Eve supper and exchange presents while watching a special television presentation featuring Walt Disney’s iconic flicks. Nordic Christmas traditions include nativity scenes and Christmas trees, julklappar (Christmas gifts), “God Jul!” (Christmas greetings on holiday cards), Jultomte (the Swedish equivalent of Santa Claus), and julbock (Christmas goat).

Christmas Traditions in Sweden

Holiday Greeting Cards

Jullkort, the first Christmas card, debuted in 1843, three years after the British postal stamp was invented. The card, which was painted by an unknown Mason, was written by John Callcott Horsley. The price of each card was less than 1 shilling, and there were 1000 of them sold. The Christmas card was a staple of the holiday season by the 1860s. It spread over the globe, including Sweden, in the decades that followed, becoming a common means of communication.

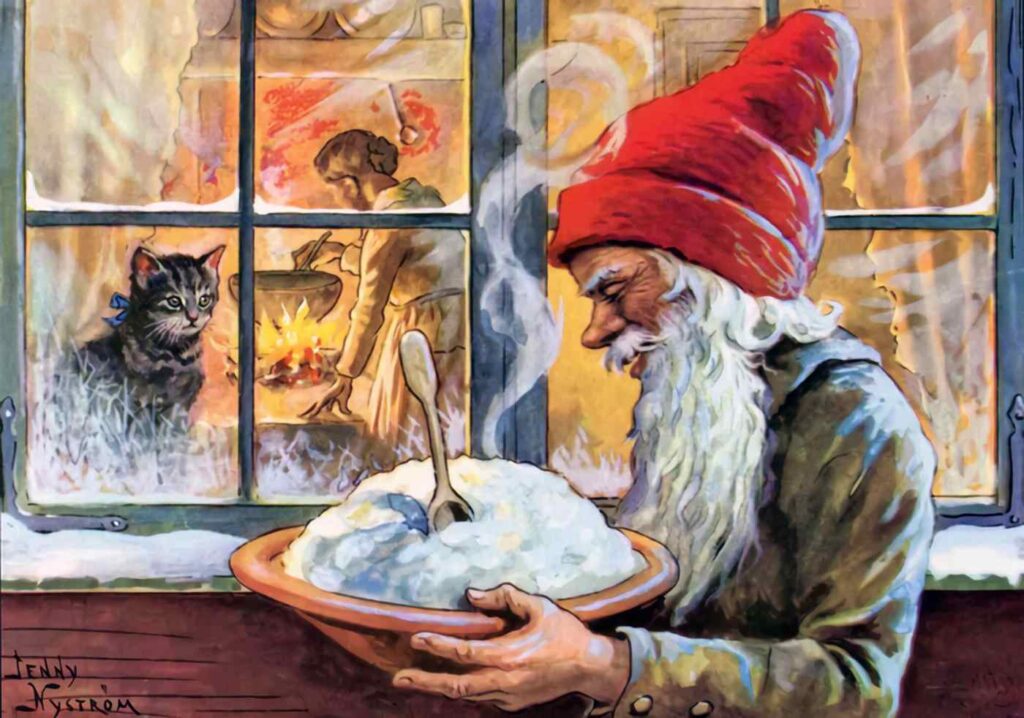

Germany quickly started printing postcards with Swedish Christmas greetings for the Swedish market when the Swedish postal agency (Postverket) instituted a half-price cut for shipping postcards in 1877. After founding an artistic publishing firm in 1890, Axel Eliasson started producing postcards and, later, Christmas cards in 1898. Jenny Nyström was employed by him as a graphic designer. She supposedly created more than five thousand postcards and a large number of them had holiday themes.

The gnomes, which she loved, quickly became the most popular design for Swedish Christmas cards; in fact, they became a hallmark that set them apart from their Catholic counterparts, whose cards often included religious themes. The first Christmas stamp was issued by the Hungarian postal office in 1943; in 1972, the Swedish postal service adopted the concept and used Jenny Nyström’s artwork to great effect.

Advent Star

Even after the Protestant Reformation, Christians continued to observe the Christian festival of Advent, which marks the beginning of their preparation for Christ’s return. Among its messengers is the Advent star, or adventstjärna in Sweden. In the spirit of Christmas and to light up their houses throughout the winter season, Swedes hang Advent stars of many forms and colors every year. In one school in the German town of Herrnhut in the 1880s, pupils and instructors created the first Advent star using paper and internal lights.

After marrying German Julia Marx in 1912, Professor Sven Erik Aurelius brought the Advent star to Sweden. Herrnhut gave them an Advent star (Herrnhuter Stern, Swedish: Herrnhutstjärna) as a wedding present, and the newlyweds displayed it proudly in their Lund house. The Advent star was well-received by Lund families. The Swedish market began selling Advent stars imported from Germany in 1934, and that’s when the name was given to them.

During the 1940s, a more basic version of the Advent stars started to be placed in windows all throughout Sweden. The star has now grown in significance to the point that it rivals the Christmas tree as a central symbol of Swedish Christmas celebrations. It represents the Star of Bethlehem, which allegedly guided the three wise men to the crib of the infant Jesus.

Christmas Tree

In Swedish Christmas festivities, the julgran (Christmas tree) serves as a unifying symbol for both modern and ancient rituals, as well as for rural and urban ways of life. According to urban legend, cows would be protected from gnomes during the Christmas season by planting evergreen trees in strategic locations, such as dung dumps. But these traditions are unrelated to the decorated Christmas tree of today. The custom of adorning a Christmas tree with candles originated in Protestant Germany during the 1600s and 1700s, but its roots may be found in southern Germany and Switzerland.

Carl August Schwerdgeburth, a German painter of the nineteenth century, painted a scene of Martin Luther and his family celebrating Christmas Eve in 1536. The scene depicts Luther lighting a candle on a table, with a little Christmas tree visible in the background. It would seem that Luther is being portrayed as the “inventor” of the Christmas tree in reproductions of this image that are displayed in several Swedish households. Ahistorical tales lend credence to this story, although the Christmas tree was really created by Protestants (or adopted by Central Asia) in Germany. Lutheranism grew so associated with them that German Catholics scornfully called it the “religion of the Christmas tree.”

Catholics gave Christmas a public and dramatic quality, whereas Lutherans and Calvinists stressed the family aspect. It wasn’t until 1632 that a Swedish soldier recuperating from wounds sustained in war in a Leipzig residence saw a Christmas tree adorned with candles that word of the tradition spread throughout Sweden. The 1740s saw the introduction of Christmas trees to the mansions of Sweden’s nobility.

Although Christmas trees were first popular among city residents and well-off country folk in Sweden, it took another hundred years for them to catch on with the rest of the country. Even back then, there were little trees that held candles on a tabletop. The first floor-to-ceiling Christmas trees appeared in the middle of the nineteenth century, and by the beginning of the twentieth century, they were commonplace in the houses of small-scale farmers and laborers.

Christmas trees started popping up in public places and malls in the 1920s. It was also common practice to use Christmas tree branches as doormats during the holidays. Despite the Christmas tree’s global rise in the twentieth century, its adoption was met with reluctance in southern Catholic nations like Italy because of their long-established practice of Nativity scenes. The mass manufacture of synthetic Christmas trees is the most recent development.

-> See also: Christmas in Italy

Scene of the Nativity

The julkrubba, or Nativity scene, has its roots in Catholic culture. Saint Francis of Assisi put up the first-ever Nativity scene on Christmas 1223 at Greccio. Part of the enigma surrounding the Nativity was conveyed by this lifelike Nativity tableau, which included an ox and a donkey. Typical Renaissance nativity scenes may be seen in churches around the world today. This artistic movement began in the 16th century in Spain and Italy and quickly expanded north of the Alps. It was forbidden to exhibit Nativity scenes in churches in Sweden following the Protestant Reformation.

Only in the nineteenth century did nativity scenes start popping up in Stockholm’s German neighborhoods. Such a Nativity scene was detailed in the diaries of author Märta Helena Reenstierna in 1804. It wasn’t until 1929 that pastor Albert Lysander of Malmö’s St. Peter’s Church had the courage to exhibit a Nativity scene he had bought in Germany, despite the fact that for a long time, such decorations were seen as quite un-Lutheran. He found inspiration in the structures seen in Protestant churches in Germany.

In the 1930s, the practice of showcasing Nativity scenes expanded from Malmö throughout the whole Skåne area. Stockholm saw the emergence of this practice in several local churches throughout the 1930s as well. But first, carefully presented in parish halls, and subsequently, in the churches themselves, are Nativity scenes. Nativity scenes quickly became commonplace throughout Sweden. To this day, they remain the only part of modern Swedish Christmas festivities that supports the holiday’s original Christian meaning.

Jultomten

The modern-day image of Santa Claus as the savior of Christmases past has its roots in stories about St. Nicholas. Leading a goat on a leash, he made his appearance on the continent in medieval mystery plays performed on December 6. In a symbolic act, St. Nicholas subdued the devil with the goat (see Krampus). It was common practice for the bearer of Christmas gifts to disguise themselves as a goat in aristocratic circles beginning in the 18th century.

Santa Claus stepped into the goat’s shoes at the close of the nineteenth century. In the 1840s, the English press published the first illustrations of Santa Claus. Comparatively, the Swedish Jultomten combines the European custom of Santa Claus bringing Christmas gifts with the Swedish gårdstomten (nisse), also known as a garden gnome or “goenisse,” who was not involved in gift-giving but rather in taking care of the farm and its animals.

Even though he couldn’t be seen, he had a smack for everyone who ignored the animals. Gnomes watch peasant yards; therefore, on Christmas Eve, hosts would leave a bowl of porridge for them. Jenny Nyström, who became known as tomtens mamma (Santa’s mother) after immortalizing these gnomes in hundreds of paintings in the 1880s, greatly increased their prominence as the primary holiday emblem.

Christmas Goat

Even though Juldagen or Christmas Day, on the 25th of December, was deemed too joyful for the celebrations of children and young adults, the festive mood quickly faded in the late afternoon or early evening of December 25th and 26th since the young people had already started a pan-Scandinavian tradition of parading the Christmas goat (julbock).

The earliest Christmas sign in Sweden is probably the straw goat, a traditional Swedish Christmas ornament that has its roots in the medieval devil, who featured in school Saint Nicholas masquerades. Later iterations used the yule goat prominently in a lighthearted Christmas play that the kids put on to collect some food and drinks for the dances. Originally used to give presents on Christmas Eve in the 18th century, the jultomten goat has now been used only as a decorative item for Christmas for more than a century.

Christmas Gifts

Christmas gifts (julklappar) were not traditionally a big part of Swedish Christmas traditions. Gifts for children were rare in affluent families in the 17th and 18th centuries, but they became commonplace in peasant homes much later. Before surreptitiously knocking on doors (Swedish: klappa, meaning “to knock on the door”), the earliest “julklappar” were just simple presents. A straw doll, a plank of wood, or even the bladder of a pig could be presented.

It was common practice to affix a poem, either humorous or insulting, to the gift. In this manner, rural communities’ Christmas festivities began to include gift-giving. Other forms of generosity, which are supposed to define Christmas, were also on display in Sweden. All farm residents were required to collect their presents. The impoverished residents of the town were remembered as they cooked bread and cast candles. Even the farm animals were given special treats on Christmas Eve, thanks to this kind spirit.

Midnight Mass

Because the Reformation restricted nocturnal devotions to a single night a year, the two morning Masses celebrated on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day in Sweden are relics of the Middle Ages. It used to be held at a much earlier hour than the current 7 a.m.

Christmas Dishes in Sweden

- Dopp and grytan (breads steeped in broth after cooking ham)

- Oatmeal with herring marinade

- Kakor (cookies)

- Saffranlussekatter (saffron buns baked on Saint Lucy’s Day)

- Pepparkaksgrisar (gingerbread pigs)

- Julöl (Christmas beer)

- Sylt (jellies)

- Julkorv (sausage)

- Pig’s trotters

- Lutefisk (dried fish soaked in a lye solution)

- Julskinka (Christmas ham)

- Köttbullar (meatballs)

- Prinskorv (small sausage)

- Janssons frestelse (a potato and anchovy casserole)

- Surströmming (sill or herring)

- Gravlax (marinated salmon)

- Ägghalvor (egg halves packed with salad)

- Turkey

While the religious parts of the Swedish Christmas celebration have all but vanished, the traditional meals served at the Christmas table (julbord) remain a secular part of the holiday and a symbol of the Swedes’ traditionalism. There has always been a strong correlation between the holiday spirit and food and drink. The traditional rules of fasting enforced by the Catholic Church provide some justification for this. Indulging in food following the conclusion of fasting was also influenced by the ritual of slaughtering a particularly fattened pig right before the holidays.

Dopp and grytan, which are breads steeped in broth after cooking ham, are examples of foods that were previously commonplace. The traditional Swedish Christmas table also reflects the influence of older culinary technology and preservation techniques. Here are a few examples: oatmeal with herring marinade, cookies called kakor, saffranlussekatter, pepparkaksgrisar, julöl, and saffron buns baked on Saint Lucy’s Day.

Additional examples include oatmeal and herring marinades. The Christmas meal used to differ by region; for instance, pike was the main course in eastern Sweden and among Swedes residing in Finland, but in northern Sweden, veal and beef were more typical. Nowadays, there are no major social or regional differences in the Christmas meal.

Uppsala University professor of culinary studies Christina Fjellström claims that it is difficult to pinpoint the exact dates when certain Swedish Christmas foods first appeared on the table because of a lack of primary sources. Due to their extensive history, dopp and grytan are likely two of the oldest foods. The Swedish Christmas table is a symbol of the blending of Christian and pagan customs (midvinterblot). Besides dopp, some of the earliest meals that are likely still around today include sylt (jellies), several kinds of julkorv (sausage), and other portions of the pig that were prepared during pagan times.

Similarly, pig’s trotters are an old cuisine that is almost gone now. Dopp and lutefisk, two delicacies with a lengthy history, are also on the decline. Other foods are starting to take center stage in their place. As it stands, julskinka (Christmas ham) is the centerpiece of most Christmas dinners. Also very popular are the meatballs (köttbullar), prinskorv (small sausage), Janssons frestelse (Jansson’s temptation), and herring (sill or surströmming). Contrary to popular belief, Christmas ham is really a sophisticated kind of pork that was traditionally reserved for special occasions. Instead, commoners would eat the pig’s head around Christmas.

Ham didn’t start appearing on Christmas tables until the 18th century, and even then, it was only in the homes of the nobility. It wasn’t uncommon for regular folks to have it on their tables around a century ago. It wasn’t until after WWII that the relatively new dish known as Köttbullar became a traditional Christmas meal. Gravlax (marinated salmon) and ägghalvor (egg halves packed with salad) are two further culinary innovations. According to Fjellström, the foods served at the Swedish Christmas table are subject to constant change, mostly as a result of outside forces. Turkey, a dish with roots in the United States and England, is gaining a lot of fans in Sweden.

Christmas Dates in Sweden

Advent encompasses the time from the first Sunday of Advent to Christmas Eve. Each of the four Sundays that fall within this time frame is known as an Advent Sunday.

- December 13: Lucia (Saint Lucy’s Day)

- December 24: Christmas Eve (julafton)

- December 25: Christmas Day (juldagen; public holiday)

- December 26: Boxing Day (annandag jul, annandagen; public holiday)

- January 6: Epiphany (trettondedag jul, trettondedagen; public holiday)

- January 13: St. Knut’s Day (tjugondag Knut, Canute Lavard)

- February 2: Candlemas (Kyndelsmässodagen; the end of Christmas).

On November 4, 1772, along with several other holidays, the regulation “The regulation of November 4, 1772, addresses the observance of the Sabbath and the alteration or cancellation of specific holidays” abolished the third and fourth days of Christmas in Sweden, which was a former observer of these days.

Advent

Advent, from the Latin adventus, means “coming,” suggesting that Jesus will return. Advent was the first Sunday of Lent, when Catholics began to fast. But there were cases when the Advent season did not coincide with fasting. A post-Epiphany fast connected with January 6th, in preparation for the Baptism of the Lord, was observed before the decision was made to celebrate Christmas on December 25th in both the West and the East. Saint Martin of Tours issued an edict in 480 establishing the three-day fasting period leading up to Christmas, beginning on Saint Martin’s Day (November 11). This term was eventually shortened to four weeks by popes who came after him.

It was then decided that this time would begin on December 13, the feast day of Saint Lucy, and that it would be further reduced. Advent was a minor festival in Swedish folklore. As the twentieth century began, the prominence of Advent was greatly diminished in comparison to All Saints’ Day. But things changed in the Roaring Twenties, and the first Sunday of Advent rose to prominence as a major liturgical celebration in the church year.

Theologians in Sweden are at a loss to explain Advent’s meteoric rise in popularity. They hold the view that the common practice of beginning the Christmas season on the first Sunday of Advent is not responsible for its popularity. This pattern evolved as a result of the transition from a system in which people made things for their personal consumption to one in which the market supplied the essentials. As a result, instead of spending time at home getting ready for the holidays, people instead shop for goods at shops, which both commercializes the holidays and makes December more fun.

Lucia

The young Christian female figure known as Saint Lucia lived in Syracuse around the close of the third century and died as a martyr in the year 304. In that era’s Christian society, her cult was like wildfire. In Venice’s San Geremia church, her remains are preserved in a glass casket. Saint Lucia and the Lucia of today both hail from Sweden, but their origin stories are quite different. Saint Nicholas, also known as Sankt Nikolaus in German, was the patron saint of students and possibly had his roots in the worship of Lucia in Sweden.

On December 6th, his feast day, which ushered in the winter festivities, people would exchange gifts. Christ Child (German: Christkindlein or Kindchen Jesus), a girl in a white gown with a wreath on her head decorated with numerous lights, supplanted him after the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century outlawed his worship. Luciper, the devil (or Lussepär in Western Swedish folklore), was a participant in a modest parade that was prepared for this event.

The Christ Child gained popularity in 16th-century Sweden under the Low German name Kinken Jes. On the other hand, the ceremony to commemorate the start of the Christmas fast (Julfastan) was postponed until December 13. Because today was also the feast day of Saint Lucia, the Christ Child was baptized Saint Lucia (Sankta Lucia). Adapted from the German Christ Child festival, the Luciamorgon (Lucia morning) celebration originated in the estates of Västergötland in the 18th century.

On the other hand, Lucifer (Lussepär) was a particularly deadly character in peasant legend, and the name Lucia was associated with him on the night of December 13, the longest night of the year according to the ancient calendar. In honor of him, this evening is known as Lussenatt. Sankta Lucia’s victory against the devil-Lussepär, on the other hand, became the only export product of Swedish folklore in modern times.

The conclusion of the fall semester and the subsequent celebration of its completion became official on December 13 as a result of a 1724 ordinance governing schools and gymnasiums. The custom of honoring Lucia at colleges was brought to widespread popularity in the first part of the nineteenth century by the inhabitants of Västergötland, and it was also adopted by the peasants of western Sweden. In 1927, a newspaper in Stockholm staged a public Lucia parade (Luciatåg) across the city, which led to Lucia’s public popularization. Lucia has been an ingrained tradition throughout Sweden since then.

Julafton

The function of julafton (Christmas Eve) in Catholic times was similar to that of “vigils” before other significant festivals. The Latin word “vigilia” means “watching” and refers to the first nightly Christian service that took place during the persecution of Christians. It is a quite recent and unique occurrence in Scandinavia that julafton has evolved into a time for exchanging gifts (julklappar), feasting (julbord), and dancing around the Christmas tree.

Since the Christmas fast (Julfastan) did not begin until December 24th, the most important celebration was originally on December 25th. Fasting was later outlawed in Protestant Sweden, but eating pig and other meats on the final day of the fast became a Christian virtue, which may have helped convert December 24th into a big feast for Lutherans.

Morning stocking stuffing with little Christmas presents, mostly for children, was a tradition that originated in England and moved to Sweden in the twentieth century. Kalle Ankas Jul, often known as Donald Duck’s Christmas, has been shown since 1960 and is seen by many families in the “television age” before Christmas dinner. After that, Santa Claus comes with presents.

Julafton for Swedish Peasants

All through December, Swedish people are counting down the days until Christmas Eve, when they celebrate Jesus’ birth. Christmas Eve was the most serious night of the year for the majority of peasant society. Farmers concluded their final responsibilities before the holiday, which included cutting and collecting wood for the celebration, cleaning equipment, and organizing the barn, after several days of hard labor. At home, the Christmas table was set, and the floor was strewn with straw, a practice known as julglädjen (Christmas joy) in certain regions. Santa Claus, a hybrid of the German Santa Claus and the Swedish yard gnome, paid a visit to Sweden on this particular day.

Folk Beliefs

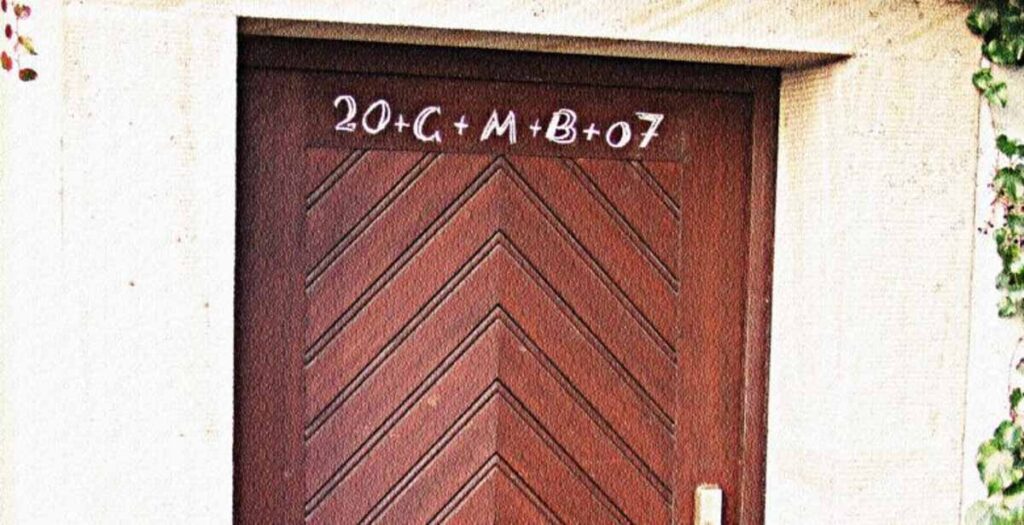

People would draw a cross on their doors and gates with chalk on Christmas Eve, according to folk beliefs, as a kind of protection against the supernatural. Traditional Christmas celebrations often include making weather predictions. Some believe that a light winter portends a chilly Easter, while others believe that a heavy snowfall in the woods during Christmas week portends a bountiful harvest.

The History of Christmas in Sweden

Everything that is now connected with Christmas in Sweden did not exist even 200 years ago. No julgran, tomten, julklappar, or julbock—no straw goat, Santa Claus, or Christmas trees. The first Swedish picture portraying traditional Christmas festivities, “Småländsk Jul” by Pehr Hörberg, dates back to circa 1800 and shows individuals enjoying porridge and beer. People sat on straw strewn out on the uneven floor to cushion their feet. Almost all of Sweden’s long-held Christmas traditions and practices have emerged in the last 150 years.

The Age of Medieval Christmas

The first Christian communities in Scandinavia emerged around the year 1000, coinciding with the start of Christmas celebrations. The festival’s roots are a mashup of Christian practices and pagan beliefs (Jul). But the secular parts of Scandinavian celebrations are few and fleeting. Even after Martin Luther forbade it, the devotion of saints continued to play an important part in medieval celebrations of holidays.

From the lowest to the highest social echelons, traditions differed. The Swedish jarls and kings, for example, tried to keep their courts and rituals the same as those of the English, the French, and the Germans. In the meantime, city inhabitants took after the practices of German merchants who had settled in Sweden, while the peasants continued with pagan practices that included gatherings of friends, family, and neighbors for feasts and drinks.

Lutheran Observances of Christmas

Despite the shift from Catholicism to Lutheranism in Sweden in the early 16th century, Christmas festivities continued unabated. As Protestant songs were introduced, services underwent a progressive transformation. It was not unusual for pastors to read the gospel in Swedish instead of the previously deleted Latin, since the Swedish language was employed for greater comprehension of God’s message, particularly around Christmas.

A striking departure nonetheless was the elimination of Christmas Eve’s midnight mass (midnattsmässan) in Sweden and in Denmark and Norway; even the Christmas morning service (julotta) was outright forbidden. While the Catholic Church celebrated festivals publicly, Luther argued that family gatherings were more important. Christmas, on the other hand, has preserved its family nature in Scandinavia since ancient times. People in the Middle Ages used to party till morning after enjoying themselves until midnight mass.

The word “julstugor” was coined to describe the shared Christmas experienced by neighbors or friends, particularly by young people around the holiday. Efforts to outlaw similar celebrations in Sweden and Denmark were mostly unsuccessful. The Stockholm magistracy firmly forbade extravagant Christmas parties on December 16, 1721. They justified the restriction by claiming that such parties undermined the sacredness of the occasion and led people to trivialize God’s name and his message.

Despite these suggestions, the public disregarded them, so numerous traditional Swedish Christmas practices such as caroling with a straw goat (julbock), a star (julstjärna), or the Luciatåg processions (Saint Lucy’s Day) featuring the lussebrud (Lucia bride) at the head of the procession and stjärngossar (boys with pointed hats decorated with stars, “star singers”) continue to be practiced today.

The 1700s

Swedish nobility and bourgeoisie started to change their Christmas traditions in the 18th century, particularly in the latter half of the century, to mimic those of their French and German neighbors. They started doing things differently, such as dressing up as Saint Lucy, putting up Christmas trees (julgran), and giving gifts (julpresenter, julklappar).

But 95% of the Swedish population that lives in rural areas kept on celebrating Christmas, just like before. However, a reciprocal process of impact between the two forms of festivity started to take shape. It became increasingly common among the rural people to give cheap and crude presents called “skamgåvor” or “skämtgåvor” (which may mean spiteful or hilarious gifts). The rustic Christmas porridge was also becoming popular among the well-to-do at the same time.

Late 1800s

The majority of the Christmas traditions practiced in modern Sweden originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the majority of these traditions shaped or imported from Germany. Christmas trees, Santa Claus, holiday window displays, holiday editions of certain newspapers and magazines, rolled-up tablecloths called jullöpare, and holiday greeting cards are all part of the traditional Swedish Christmas repertoire. Imports of mass-produced Christmas decorations (julpynt) and presents from the continent pushed these festivities to evolve.

Also, the Swedes were quick to make friends on the continent and learn about their traditions and customs. Santa Claus, for instance, was completely unknown in mid-nineteenth-century Sweden, where a straw goat (julbock) served the same purpose. The traditional straw goat was replaced by Santa Claus in Sweden via the mediums of chocolate, china, postcards, and books. It was also considered that the rural populace held an inherited, particularly “primitive” culture, which was a major motivating element according to national romanticism.

It was important for the nouveau riche, the established bourgeoisie, and those moving to cities from the countryside to work in factories to preserve their cultural traditions. At the same time, a patriarchal family model evolved, with the father taking center stage as the one to bless the guests, light the Christmas tree candles, and slice the ham for the holiday feast. Simultaneously, traditions passed down from the upper to the lower classes spread like wildfire, and by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Christmas trees were commonplace in urban centers and rural towns alike.

Modern Era

There were not many changes to the Swedish Christmas tradition throughout the twentieth century. Germany supplied the red Bethlehem stars, Advent calendars, and mistletoe, while England supplied the candlesticks. Excessive food abundance and commercialization were commonplace at traditional festivals throughout this century. Conversely, a mindset that prioritized restraint and the redistribution of excess resources to those in need developed.