The Plague Was Not Only in the Middle Ages

It is commonly thought that the word “plague” is associated with the grim and unclean Middle Ages. It was during this period, between 1346 and 1353, that a wave of the disease later named the “Black Death” swept across Europe. However, few remember that this epidemic was neither the first nor the only one.

Historians identify three waves of the plague. The first pandemic originated in Central Asia in the mid-6th century, likely in what is now Kyrgyzstan.

The epidemic reached Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, during the reign of Emperor Justinian I — hence it was named the “Justinian Plague.” The plague raged until the mid-8th century and killed between 15 and 100 million people, equivalent to 25–60% of Europe’s population at the time. Exact numbers, however, are impossible to determine — it happened a long time ago, as you can imagine.

The second wave is the well-known medieval “Black Death.” From 1348 to 1352, it spread throughout Europe, reaching even England, Scandinavia, and Russia. The bubonic plague wiped out, according to various estimates, between a third and half of Europe’s population — that is, between 75 and 200 million people.

Finally, the third pandemic occurred in the 19th century. It again originated in Central and Southeast China but spread via trading ships to Hong Kong, Bombay, Egypt, Australia, Paraguay, Venezuela, Peru, Russia, the USA, Brazil, Bolivia, Cuba, and other countries. The worldwide death toll is estimated at 15 million — much less than in the Middle Ages, but still an imposing figure.

To this day, the plague remains undefeated. About 200 people die from it worldwide each year, mainly in poor countries like Madagascar, Congo, and Peru.

Even in nearby Mongolia, the plague is still present. It mainly affects small rodents such as shrews, marmots, and ground squirrels, as well as some local residents who skin and eat them.

In Russia, natural foci of the plague are found in Siberia, Tuva, the Urals, the North Caucasus, and Altai.

Mongols Used the Plague as a Biological Weapon

For a long time, scientists were unsure where the plague in medieval Europe came from. However, modern research has shown that the second wave of the disease, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, appeared in Mongolia in 1320. It arrived in China and India with nomadic tribes and then spread across the continent with the trading caravans of the Great Silk Road.

In 1347, Kipchak Khan Janibek laid siege to the Genoese trading port of Caffa in Crimea. Today, this place is known as Feodosia. The siege seemed to be going well until an outbreak of plague erupted in the Khan’s camp.

A significant part of the personnel became incapacitated due to their poor health, characterized by a complete loss of vitality.

In short, Janibek’s forces suffered such heavy sanitary losses that his army simply disbanded. The Khan waved his hand and retreated from Caffa’s walls, having first catapulted a dozen or so plague-infected corpses into the city to ensure the Genoese wouldn’t be bored either.

From Caffa, trading ships spread the disease throughout the Mediterranean, from where it penetrated deep into Europe.

The Causes of the Plague Were Attributed to Planetary Alignments, Sins, and the Schemes of Lepers

Today, we understand well how the plague works. The bacterium Yersinia pestis is carried by fleas living on rodents, such as rats or marmots. The plague bacterium forms a special biofilm in the intestines of insects, preventing them from defecating. The poor flea bites a rat, fails to digest the blood, and regurgitates it back into the wound, now along with the plague bacillus.

However, in the Middle Ages, microscopes had not yet been invented, so people didn’t delve into the details of these creatures’ lives. The best minds of the time did not consider such mundane causes for the plague; they looked more to the heavens.

For example, 14th-century scholars from the University of Paris believed the “Black Death” epidemic was caused by a “triple conjunction of Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars in the 40th degree of Aquarius on March 20, 1345.” Astrology in the Middle Ages was an important branch of medicine. After all, stars and planets were thought to have a direct influence on human destinies, including their illnesses, right?

It was believed that these three closely aligned celestial bodies created miasmas — poisonous air vapors that descended to Earth and caused the plague.

Other scholars thought that comets, considered harbingers of disaster in the Middle Ages, brought the disease to Earth. From 1300, six of these celestial bodies, including the famous Halley’s Comet, were observed in Europe.

This theory long dominated medicine and explained not only the appearance of the plague but all diseases. They supposedly arose simply from bad air and foul smells. And indeed, in a plague barrack, the atmosphere is somewhat unhealthy and the smells unpleasant. Therefore, the plague is caused by odors. Logical? Logical.

Thus, many residents of medieval Europe concluded that they should rarely open windows to prevent miasmas from coming in from the street. They also sought to improve the air inside their homes with perfumes, flowers, and aromatic plants like garlic.

Clergy and theologians categorically stated that diseases were sent by God as punishment for sins, so to rid themselves of the plague, one needed to pray, fast, and listen to sermons.

Meanwhile, the Church did not recommend bathing or removing fleas and lice: public baths were considered sources of debauchery, and “warm water could give good Christians impure thoughts.” Fleas were even called “pearls of God” and a sign of holiness, for they “partook of Christian blood.”

Saint Benedict was cited as an example, declaring, “Those who are healthy, especially the young, should rarely bathe.” Likewise, Saint Agnes of Rome, who died without ever bathing so as not to wash away the holy water of her baptism.

Some believers, who took the calls to repent and pray too much to heart, formed the flagellant sect in the mid-13th to 14th centuries. This group, particularly popular in Switzerland and Germany, consisted of people who traveled from town to town, whipping themselves and others until they bled. Through asceticism and mortification of the flesh, they sought to appease God and stop the epidemic. Unfortunately, they only succeeded in spreading it further, as they carried fleas on themselves. It was, in particular, the flagellants who brought the plague to Strasbourg, which had not been affected until then.

Finally, medieval Europeans believed that Jews, who supposedly poisoned wells out of hatred for good Christians, and lepers, who spread the disease on the devil’s orders, were the carriers of the plague.

This led to numerous pogroms in Jewish quarters and leprosariums. However, as you understand, these executions did not stop the disease.

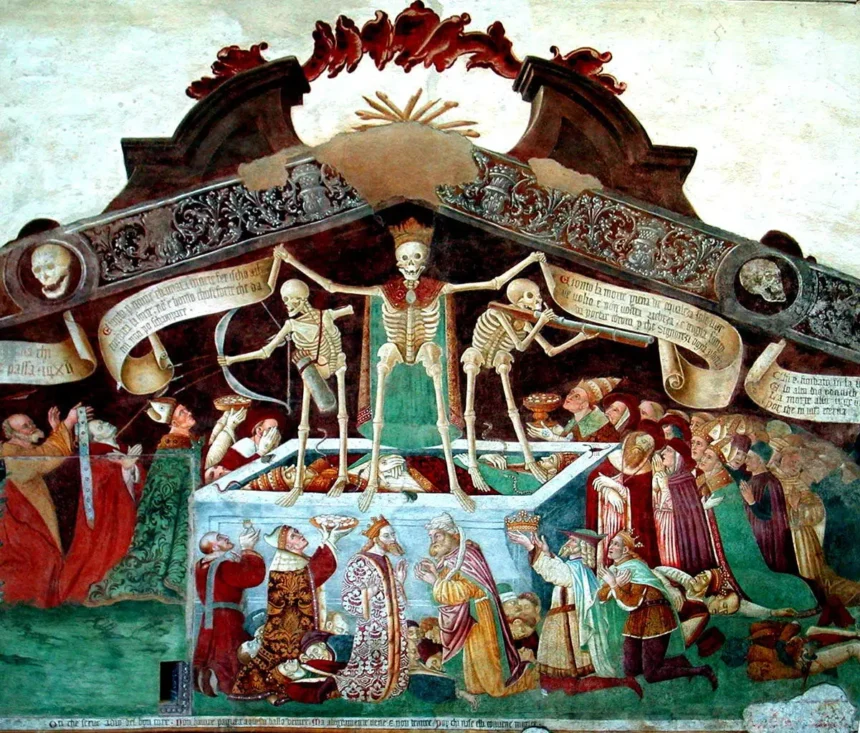

Plague Doctors Beat Patients with Canes and Took Wills

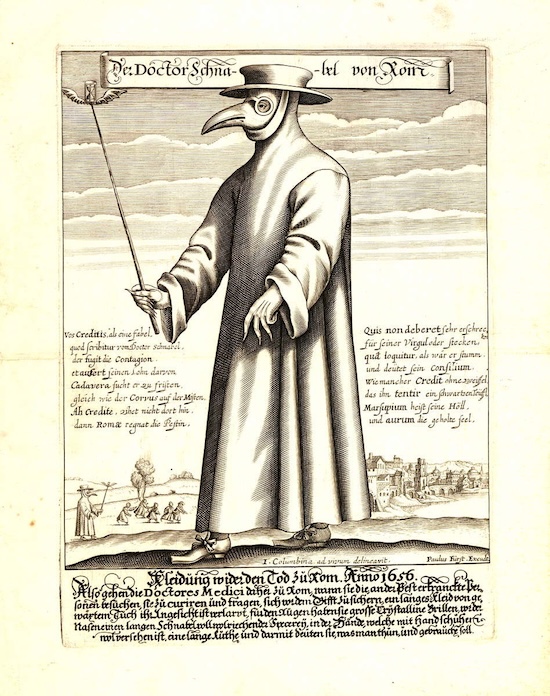

The “Black Death” is now associated with plague doctors—colorful figures in black cloaks, hats, and masks with beaks, making them resemble birds. In modern culture, they are considered either villains who conducted inhumane experiments on patients or, conversely, the first heroes of medicine who sought to heal the sick despite the imperfections of science and the obstacles posed by the church.

In reality, the image of the doctor in the distinctive mask and cloak only appeared at the end of the Middle Ages. Before this, doctors dressed in whatever they could manage.

It was not until 1619 that the physician of King Louis XIII of France, Charles de L’Orme, invented an outfit made of Moroccan goatskin: boots, breeches, a long coat, hat, and gloves modeled after a soldier’s canvas coat that covered the body from neck to ankles.

Doctors were advised to cover their faces with a mask with a beak in which dried roses, cloves, lavender, mint, juniper berries, myrrh, and other aromatic substances were placed. It was believed that pleasant smells protected against the plague, which was thought to be spread by miasmas.

To some extent, the costume was indeed useful, but not because of the roses in the beak. It was because it was coated in fat, wax, and fragrant oils, which hindered fleas from crawling on the doctor. It was, in a way, the first hazmat suit in history.

However, doctors did not connect fleas with the plague. They covered themselves in fat to prevent their clothes from being torn off by unruly patients. Thus, the protective properties of the costume were accidental. The pneumonic form of the plague, however, spread through the air without any odors, and the aromatic herbs did not save the doctors—mortality among them was still high.

In addition to the greasy, slippery costume, a heavy cane helped doctors maintain social distance from their patients.

In most cases, plague doctors were just apprentices of surgeons, interns starting their careers, or sometimes even people who came from the streets.

As a result, they often did not even try to treat the sick. Instead, they transported and buried corpses, registered the dead and infected for statistics, and took the last will of the dying, certifying their wills. By the way, there was no prohibition against robbing patients and extorting money from them.

Plague doctors would bleed the sick and apply leeches, which, naturally, were not particularly effective. In addition, they would rub human feces into buboes (swollen lymph nodes caused by the plague) and let chickens peck at the growths on patients’ bodies, believing the birds could “suck out” the disease.

However, some doctors were real surgeons who genuinely helped the sick. For example, the French doctor Guy de Chauliac once contracted the plague. He did not panic and went into self-isolation. While in quarantine, he lanced and cauterized his own buboes.

The pain was, of course, excruciating, but de Chauliac recovered and subsequently healed many more people using the same method. Lancing and cauterizing buboes did not always help, but it worked better than leeches.

The Plague Ultimately Benefited Humanity

It might seem insane that such a tragedy as the “Black Death” epidemic could have positive consequences. However, modern historians believe that, in the end, the plague contributed to the development of human civilization since it was thanks to the plague that the Renaissance began.

The upheavals caused in European society by the terrible disease led people to think more about their earthly lives and enjoy them, rather than focus solely on spirituality and heavenly rewards in paradise. It was precisely due to the weakening of religious morality and the church’s influence that the Renaissance era was marked by outstanding achievements in art and culture.

Had Michelangelo tried to sculpt a naked David in the 13th century, he would not have fared well.

Moreover, the need to find a cure for the plague prompted the thinkers of that era to move away from theology and engage in more practical endeavors such as chemistry and biology. While they did not invent a panacea, they did come up with new types of gunpowder and medicines, as well as rat traps, distillation devices, glasses, chronometers, and other useful inventions.

Additionally, the medieval plague brought an end to the feudal era, as the reduction in the peasant workforce increased the cost of labor. Many lands previously dedicated to agriculture were freed up and converted to pastures, allowing even the poorer sections of the population to consume meat and milk, which had previously been available only to the wealthy.