Elizabeth Charlotte of Bavaria (1652-1722), known as the Princess Palatine, was the second wife of Monsieur Philippe d’Orléans, brother of Louis XIV. A renowned letter writer, she was also nicknamed Madame Europe or the “Gossip of the Grand Siècle”.

Elizabeth Charlotte of Bavaria: A Coveted Match

Born in May 1652, Elizabeth Charlotte of Bavaria was nicknamed the Princess Palatine because she was the daughter of Charles Louis, Elector Palatine of the Rhine. She was also the ancestor of most Catholic princes and of Marie Louise (2nd wife of Napoleon Bonaparte), great-grandmother of Marie Antoinette and the emperors Joseph II and Leopold II, great-granddaughter of a King of Bohemia as well as a King of England and Scotland. Skinny at birth, she became plump at six, played with her brother’s swords and guns, walked in her native Palatinate picking grapes, spoke dialect, and listened to folk tales. Torn between estranged parents, her aunt Sophie of Hanover took her under her wing for five years, teaching her languages, dance, music, and writing (she would keep fond memories of Christmas, Carnival, and Pentecost celebrations).

When her parents spoke to her about marriage, she was eighteen (several suitors such as William of Orange Nassau, the Prince of Denmark, the King of Sweden, the Electoral Prince of Brandenburg, the heir to the Polish Duchy of Courland), but she wished for a true love marriage. Thanks to the Palatine Princess Anne of Gonzaga, Elisabeth Charlotte converted to the Roman religion, then was married by proxy in November 1671 to the Duke of Orléans (a contract where Philippe received all his wife’s assets!). She arrived in France completely abandoned by her family, crying incessantly during the nine-day journey. Her trousseau consisted of “a blue taffeta dress, a sable scarf, six night shirts and as many day shirts”.

Madame was surprised at the sight of Philippe, of modest height, perched on high heels and adorned with rings, bracelets, and jewels: “without looking ignoble, Monsieur was short and plump, with very black hair and eyebrows, large dark eyes, a long thin face, a large nose and a too-small mouth with ugly teeth. However, the clothes are magnificent“. As for Monsieur, he could only say: “how could I sleep with her?“. She was not a beauty, but not ugly either. Blonde, fresh, massive, with rosy cheeks, blue eyes, fair complexion. She lacked the grace, seduction, and charm of the Court. She formed, with Philippe, a couple with reversed roles: he effeminate, small, precious, coquettish; she masculine, robust, simple, natural. The ten-day honeymoon at Villers-Cotterêts was up to Philippe’s sumptuous standards. The king was quickly won over by Madame, who spoke fluent French. He even pitied her, knowing his brother and his attractions.

Princess Palatine: Wife of Philippe, the King’s Brother

The couple got along well at first. Elisabeth Charlotte discovered Saint Cloud “the most beautiful place in the world“, the Palais Royal and Paris (which she would hate for life, due to the noise and smells), the ovations of the people who would always love her… and the minions whom she distrusted. She did not meddle in Philippe d’Orléans’ affairs, but the most disturbing thing was that he used Elisabeth Charlotte’s assets to offer gifts to the minions!

Not having had a boy yet, Philippe did his duty: Alexandre-Louis was born in June 1673 but would only live for three years, then Philippe Duke of Chartres future regent in August 1674, Mlle de Chartres in September 1676. From this date on, they slept in separate rooms. Elisabeth Charlotte would later write: “I was quite pleased, for I never liked the business of making children. When His Highness made this proposal to me, I answered yes, gladly, Monsieur, I will be very content provided you do not hate me and continue to have some kindness for me…“. Especially since Philippe had transmitted to her “a beautiful disease“! She quickly replaced his presence in her bed… with 6 spaniels!

The following ten years (the golden age of music, letters, theater) were the best for Elisabeth Charlotte: she discovered Versailles, enjoyed walks in the gardens, was highly appreciated by the king for her frankness, uprightness, spontaneity, especially her lack of hypocrisy. Having common tastes, he invited her to hunt, to the theater, to the opera, to evening gatherings. Louis XIV, won over by her humor and common sense, offered her his friendship.

From 1680, “the wind turned”. Elisabeth Charlotte lost her father and Anne of Gonzaga, faced a plot organized by the minions to oust her, destroying the good understanding between the two spouses, Philippe’s double tertian fever, the king destroyed the Palatinate, Philippe suppressed positions in his wife’s household, imposed Effiat as their son’s tutor… Madame rebelled, the king reprimanded her and added: “if you were not my sister-in-law, I would have dismissed you from the court“. He turned away from her… the king began the 2nd part of his life: more serious, more pious, Elisabeth Charlotte’s frankness almost offended him. She lost all credibility and did not realize the rising favor of Mme de Maintenon.

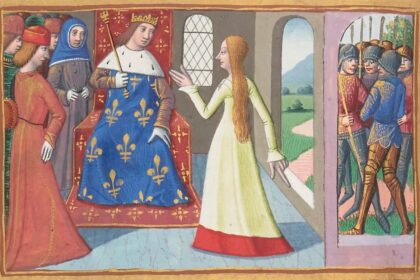

The worst was reached when the king married the Duke of Chartres (in order to channel him as he was too gifted in war) to Mlle de Blois, his illegitimate daughter. Elisabeth Charlotte left the salons of Versailles Castle, in the midst of courtiers “like a lioness from whom one tears away her cubs”. She felt increasingly alone and lost. Philippe no longer taking care of her, she wished to enter a convent. She complained to the king who replied: “as long as I live, I will not consent to it. You are Madame, and obliged to hold this post, you are my brother’s wife, so I will not allow you to make such a scene… I do not want to deceive you, in all the quarrels you may have with my brother: if it’s from him to you, I will be for him; but also if it’s from other people to you I will be for him“. Only her aunt Sophie of Hanover was there for her. Elisabeth Charlotte’s only consolation was her mail, she wrote freely, recounted her misfortunes, depicted the Court’s antics, without forgetting anyone. Her letters were opened and shown to the king…

“Gossip of the Grand Siècle”

Elisabeth Charlotte and Philippe, neglected by the king, grew closer. She took on worrying proportions, he was worn out, tired by his excesses. Wanting to defend his son, Monsieur got so angry and upset with the king that he had an apoplectic fit. On June 9, 1701, Elisabeth Charlotte was alone, threatened with spending the rest of her life in a convent. Following the advice of her entourage, she made peace with Madame de Maintenon on June 11… everyone embraced but the atmosphere remained tense.

Having neither the Palais Royal nor the domain of Saint Cloud left, she was left with the old castle of Montargis and the king’s goodwill! She settled definitively at Versailles, became philosophical and aspired “only to spend her life peacefully”. Serene, no longer under the pressure and sarcasm of the minions, in good friendship with the king and Mme de Maintenon, the rest of her life alternated between joy and sorrow: the happiness of having a new grandson on her daughter’s side neutralized the grief caused by the death of her favorite dog, the birth of the new Duke of Chartres had no effect on her, her aunt Sophie of Hanover’s daughter died of a throat tumor. Elisabeth Charlotte fell seriously ill by twisting her foot and knee, and deprived of “Marly”, hunts and walks, she wrote: “one changes nature as one ages“. She went through the very harsh winter of 1709 with its numerous deaths, and noticed in July 1710 that her treasurer had subtracted 100,000 écus from her…

She spent more and more time in her study, playing the guitar, enlarging her collection of beautiful books (3000 volumes) and antique medals (964). She navigated between Virgil, Honoré d’Urfé, Saint Evremond and the Bible. Interested in medicine and sciences, she spent moments studying insects and other things through the three microscopes she owned. Her twenty-page letters did not serve History, they were a testimony of her time, “these little nothings” of everyday life that one tells, a bit like nowadays. In our time, we would say “she chatters”.

Between Melancholy and Lucidity

Elisabeth Charlotte was infinitely sad at the death of her aunt Sophie in 1714 and no longer had a taste for life. At the king’s death, she fainted, so real and deep was her grief. Among her occupations, she laid the first stone of the church of the Abbey-aux-Bois, rue de Sèvres, she supported her son during the Cellamare conspiracy. Finally, in 1719, Mme de Maintenon passed away at St Cyr! She exclaimed: “the old Maintenon has croaked. It would have been a great happiness if this could have happened some thirty years ago“. Another contentment: the death of the Marquis d’Effiat. She reconciled with doctors and accepted certain prescriptions, but she was wearing out, tiring very quickly.

No longer able to walk, but still of sound mind, she was perplexed by this new Parisian wealth produced by the Law system. She still had time to attend the coronation of Louis XV before dying. Courageous to the end, she passed away on December 8, 1722, at the same time as a solar eclipse.

Mathieu Marais would say: “we lose a good princess, and that is a rare thing“. A princess of the old times, preserving and applying the principles of propriety, always ready to serve the people of her household, having had difficulty understanding the evolution of mores during the Regency.