In the Middle Ages, the Contents of Chamber Pots Were Dumped Out of Windows

It is believed that this was a very common practice. In 13th century France, there was allegedly even a law requiring residents to shout three times, “Watch out, water!” before emptying a chamber pot.

- In the Middle Ages, the Contents of Chamber Pots Were Dumped Out of Windows

- Wide-Brimmed Hats Were Needed to Protect Against Waste Being Dumped

- Isabella of Castile Bathed Twice in Her Life

- Louis XIV “Stank Like a Beast”

- Crusades Brought Soap to Europe

- Europeans Considered Russians Perverts Because They Bathed Once a Month

- In the Middle Ages, People Ate with Their Hands and Had No Manners

- So Much Filth Flowed Through City Streets that People Walked on Stilts

However, this is not true. People in the Middle Ages did use chamber pots, as toilets had not yet been invented, but they would empty the contents into cesspits and ditches, not onto the street from a window.

Of course, there may have been some eccentric individuals who did throw waste out of a window, but they probably did not have an easy time.

For example, in 14th century English cities, someone could be fined 40 pence for throwing garbage out of a window — an amount that many ordinary workers earned in a month. That could buy several barrels of beer, a couple of sheep, or a grown pig, so one would have to think twice about whether it was worth it.

It’s also unlikely that the residents of medieval towns would have been thrilled about human waste being dumped on their heads from windows. Records have survived of a man named Thomas Scott who urinated in the street in 1307, which angered two other townspeople. They demanded that the troublemaker go to a public restroom, but when he responded rudely, they beat him and wounded him with a knife.

Another man who threw a spoiled smoked fish out of his window was beaten so badly by his neighbors that he barely recovered.

As you can see, people did not go easy on dirty habits back then.

Wide-Brimmed Hats Were Needed to Protect Against Waste Being Dumped

This myth is related to the previous one. It is also claimed that such hats were worn by middle-class people attending medieval theaters, forced to crowd in the pit. When lords and ladies lounging on the balconies and upper boxes threw leftovers or sneezed down on the commoners, the brims of these hats would help keep their heads relatively clean.

In reality, wide-brimmed hats were made for the obvious purpose of protecting against rain and sun. They were common in all cultures, not just European ones.

In the Middle Ages, they were most often worn by peasants and pilgrims. For the latter, the wide-brimmed hat eventually evolved into the capello romano, or saturno, as well as the galero — hats worn by clergy.

Additionally, they were favored by soldiers, who often had to wander outside in bad weather or heat. Over time, their hats turned into the famous feathered hats of musketeers, known as cavalier hats. And when firearms became widespread and the wide brims began to interfere with aiming, they started pinning them up with pins, creating the tricorne.

Nobles also liked such hats, but not because poor people often poured chamber pot contents on their heads. Aristocrats simply considered pale skin a sign of nobility, while a tan was seen as a distinctive feature of commoners who worked in the fields.

Isabella of Castile Bathed Twice in Her Life

Experts in the unclean and suffering Middle Ages often cite Queen Isabella I of Castile, who ruled Spain in the 15th century. Allegedly, this lady was so devout that she considered bathing a sin and proudly claimed to have bathed only twice in her life — at birth and before her wedding.

All this to avoid washing away the holy water that touched her skin during baptism.

However, this is a myth, with no evidence to support it. There is only this legend: in 1491, the queen laid siege to the city of Granada, intending to expel the Muslims from Spain. She vowed not to bathe or change clothes until the city fell.

Unfortunately for her, the siege dragged on for eight months, during which time Isabella’s clothes took on an unpleasant grayish-yellow tint that artists later named “isabelline.”

The legend is quite murky: historians can’t determine whose name the color was originally based on — Queen Isabella I of Castile or Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia of Spain. There were also rumors that the latter made a similar vow not to bathe when she began the siege of the Dutch city of Ostend in 1601. And the fighting went on for three years.

As a result, the stories of these two Isabellas often get confused in tales about the unwashed Middle Ages, making it difficult to determine if there is even a grain of truth in the story.

At that time, people often made strange vows to demonstrate steadfastness and win divine favor in battle through their suffering. For example, some knights vowed not to eat meat or shave during war, covered one eye with a patch, or deliberately refused to use fire to warm themselves.

But even if we assume that the legend has a basis in reality and the queen did vow not to bathe for several months, this means that such behavior was unusual for her in normal times and was seen as a real ordeal. And after the city was taken, she did bathe again.

Louis XIV “Stank Like a Beast”

Another figure allegedly known for avoiding bathing was Louis XIV de Bourbon, King of France—also known as the “Sun King” or “Louis the Great.” According to an internet myth, this monarch supposedly bathed only two or four times in his entire life and did so only under doctor’s orders. However, the idea of Louis XIV‘s poor hygiene can hardly be explained by medieval customs, given that this was already the Early Modern period.

According to some “Russian envoys” (or “Cossacks” in another version), “His Majesty stank like a wild beast.” Sometimes, this phrase is even attributed to Peter the Great himself. However, the Tsar could not have said this because, by the time he visited Versailles in 1717, Louis XIV had already been dead for a couple of years.

There are no historical records of Russian envoys or Cossacks making such a statement.

Most likely, this anecdote was invented by blogger Denis Absintis, the author of a book about the “dirty and sick” Middle Ages, titled Zlaya Korcha (“Evil Cramp”). While describing the unsanitary conditions of that time, he might have gotten a bit carried away and “slightly” exaggerated.

Moreover, in his work, he seriously references the writings of Patrick Süskind—a supposed “Swiss chronicler.” In reality, Süskind is a contemporary author known for his novel Perfume.

In fact, Louis XIV bathed regularly. Otherwise, it would be hard to understand why he spent a fortune on bringing running water to Versailles and building baths and swimming pools there. As contemporaries noted, His Majesty was an excellent swimmer and could swim across the Seine on a dare.

He built a Turkish-style bath in his palace and regularly took baths there, often in the company of court ladies. And when he could not bathe while traveling, he ordered his valets to wipe his body with grape spirits and sprinkle him with perfume.

Crusades Brought Soap to Europe

There’s a claim that Europeans only started bathing after the dirty Crusades stole the secret of soap-making from the Muslims. Before that, the residents of Europe supposedly didn’t know about it at all.

In reality, Europe had entire guilds of soap-makers as early as the 6th century. It’s unclear how they managed to produce their products if the First Crusade only took place in the 11th century.

Crusades did bring back a specific recipe for soap from Palestine—one made with olive oil. When European soap makers started using olive oil instead of animal fat, their products began to smell better. Wealthy people then switched to this new soap. But to say that Europeans didn’t use soap before the wars with the Muslims is inaccurate.

Europeans Considered Russians Perverts Because They Bathed Once a Month

This statement also circulated on the internet, thanks to the author of Zlaya Korcha. However, there’s a catch: he provided no sources for this claim.

Bathhouses were common in Europe at that time, both private ones (for wealthy gentlemen) and public bathhouses. The latter often doubled as bakeries or blacksmith shops to save firewood and not waste the heat from the ovens when there was no need to heat water. Here is a description of such establishments in the city of Erfurt in the 13th century:

The bathhouses in this city will bring you true pleasure. A beautiful young girl will rub you well with her tender hands. An experienced barber will shave you without a drop of sweat falling on your face. A pretty woman… will skillfully comb your hair. Who wouldn’t steal a kiss from her if they wished?

Civilization of the Medieval West, Jacques Le Goff

Yes, bathhouses were often combined with brothels, and it was easy to receive additional services from the bath attendants besides washing. The Church turned a blind eye to these minor sins—in England, for example, bishops taxed bathhouses located within their dioceses.

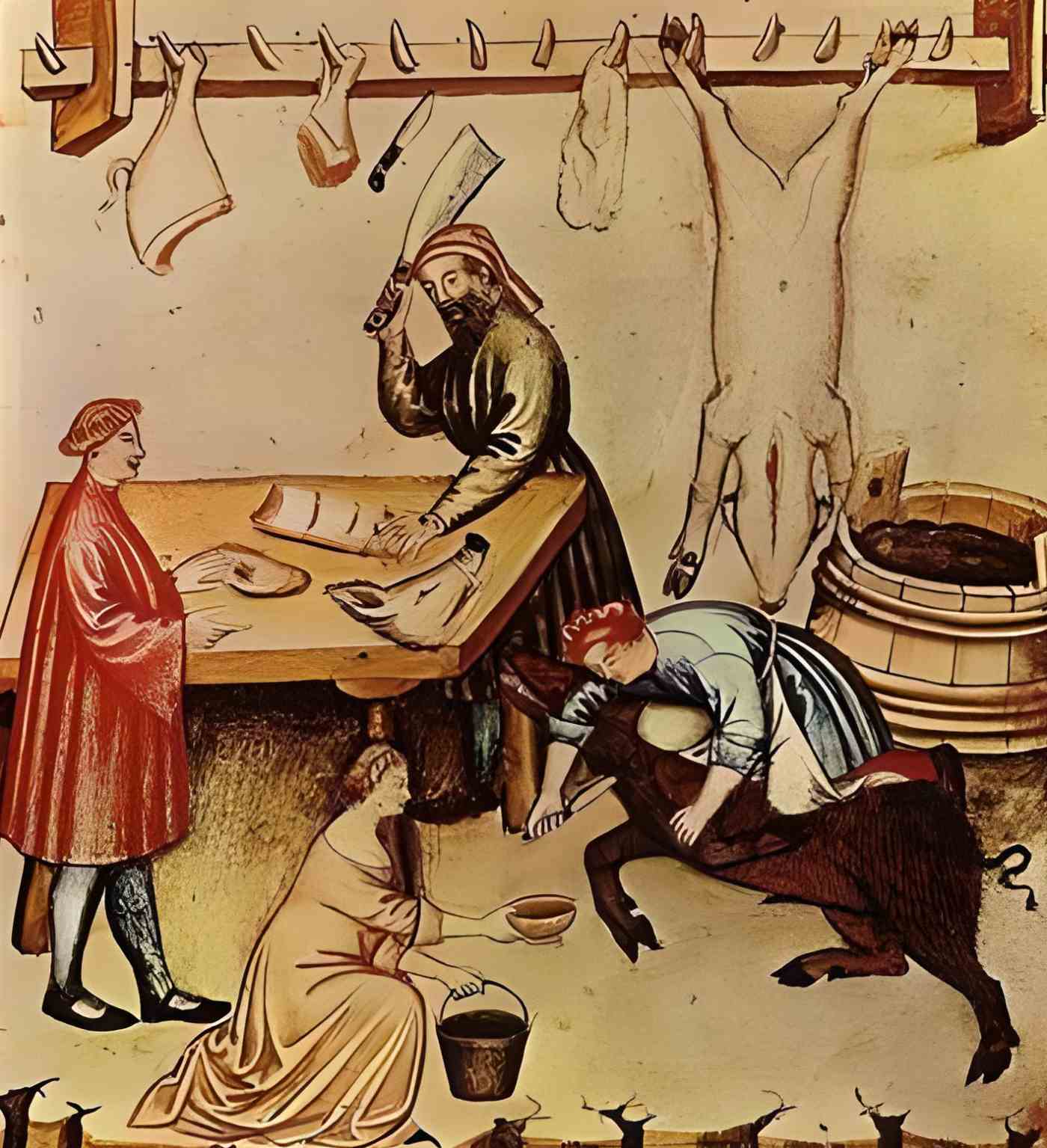

In the Middle Ages, People Ate with Their Hands and Had No Manners

Medieval people, even noble lords, are often depicted as very ill-mannered diners who grabbed food from the table and ate it with their hands. The myth goes that forks were only brought from the East towards the end of the era, and before that, people had to use their dirty fingers.

However, medieval table etiquette can be judged from a 15th-century manuscript titled “Les Countenance de Table.”

……and let your fingers be clean, and your fingernails well-groomed. Once a morsel has been touched, let it not be returned to the plate. Do not touch your ears or nose with your bare hands. Do not clean your teeth with a sharp iron while eating. It is ordered by regulation that you should not put a dish to your mouth. He who wishes to drink must first finish what is in his mouth. And let his lips be wiped first. Once the table is cleared, wash your hands, and have a drink.

Les Countenance de Table, 15th-Century Manuscript

As you can see, it doesn’t quite resemble a scene from the comedy Black Knight, where the king served peas with the same hand he had just scratched himself with, and then fed the dog.

Forks indeed appeared in Europe relatively late, in the 1600s. Before that, people only used spoons and knives, and a noble lord carried his eating knife on his belt—it was considered foolish to show up at a feast without your own cutlery. When medieval aristocrats finally acquired forks, they initially carried them in sheaths, too—a rather amusing custom.

So Much Filth Flowed Through City Streets that People Walked on Stilts

Medieval European cities, of course, were not as well-kept as modern ones, but authors of articles and books about the “grim Dark Ages” sometimes exaggerate too much.

For example, there is a myth that streams of feces, manure, and other filth, poured from the windows and doors of surrounding houses, flowed down the streets of settlements. People were supposedly forced to walk on stilts to navigate the streets.

It is also said that heels were invented to allow people to move through dung-covered streets without getting dirty.

Sounds disgusting, doesn’t it? However, images of medieval sufferers on stilts, which are often used to illustrate such statements, are misunderstood by modern people.

These devices were indeed worn, but not by city dwellers. Rather, they were used by peasants, who used them to move through wet fields and swamps without getting stuck. Additionally, stilts were used to harvest crops from tall trees and for entertainment—there were even amusing battles and tournaments held on them.

It was not necessary to move around on stilts in cities, as filth did not flow down the streets. There were designated sewage channels for this purpose, and they were covered to prevent odors from spreading. Special responsible individuals made sure these channels did not overflow.

As for heeled shoes, ladies sometimes wore them to avoid getting their dresses dirty—not in filth, but in rain puddles. Later, men adopted this fashion, using such shoes to emphasize their status and increase their height.