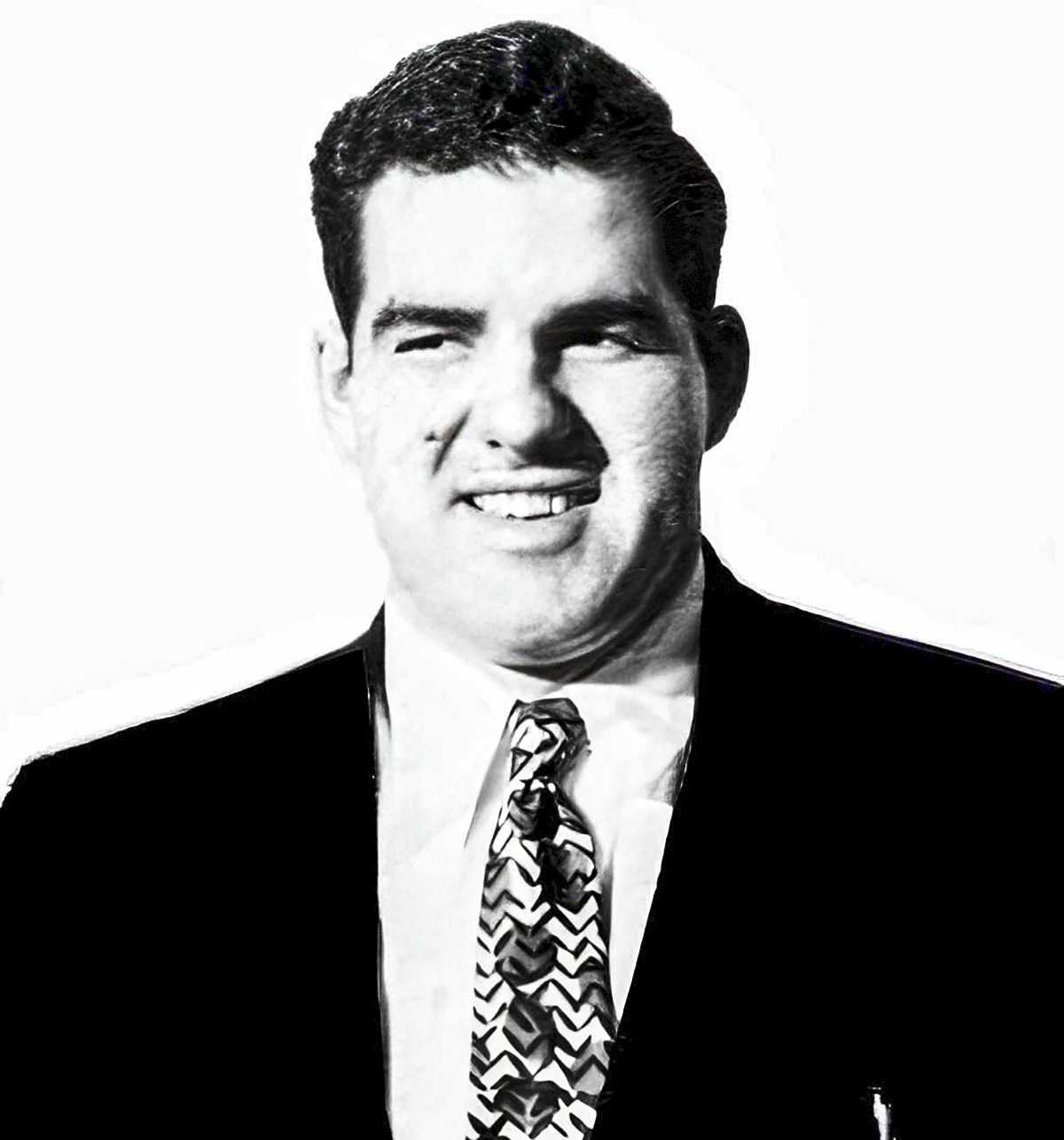

Harry Daghlian was an American physicist of Armenian descent. He was born (as Haroutune Krikor Daghlian Jr.) on May 4, 1921, in Waterbury, Connecticut, and died on September 15, 1945, in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Harry Daghlian is known as the first person ever killed in a nuclear accident.

Harry Daghlian’s Life

Harry Daghlian was the oldest of Haroutune Krikor Daghlian and Margaret Rose’s three children. His father had found work as a radiologist at Lawrence & Memorial Hospital in New London, Connecticut, so the family relocated there soon after Harry’s birth.

In New London, where Harry went to elementary school, he was a member of the orchestra and played the violin. Daghlian was the best student in his class because of his early interest in and aptitude for mathematics and science. His uncle, Garabed K. Both his father and his uncle, Garabed K. Daghlian, who taught physics and astronomy at Connecticut College in New London, encouraged Harry to pursue his interests in the subject.

Harry Daghlian graduated from Bulkeley High School the same year, 1938. Subsequently, he enrolled at MIT to study at the undergraduate level. Daghlian transferred to Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, after two years, and he graduated with a Bachelor of Science there in the spring of 1942.

Then he started attending graduate school on a fellowship. The Manhattan Project, which included the creation of an atomic weapon, required the recruitment of qualified individuals from all across the country. Robert Oppenheimer enlisted help from academics he knew at several American colleges. In the spring of 1943, he met Purdue University professor Marshall Holloway at Los Alamos after hearing him give a lecture.

This time around, Oppenheimer employed Holloway and three others from his crew. They began off at Los Alamos in the autumn of 1943, with Harry Daghlian likely joining them in the spring of 1944 after finishing his studies.

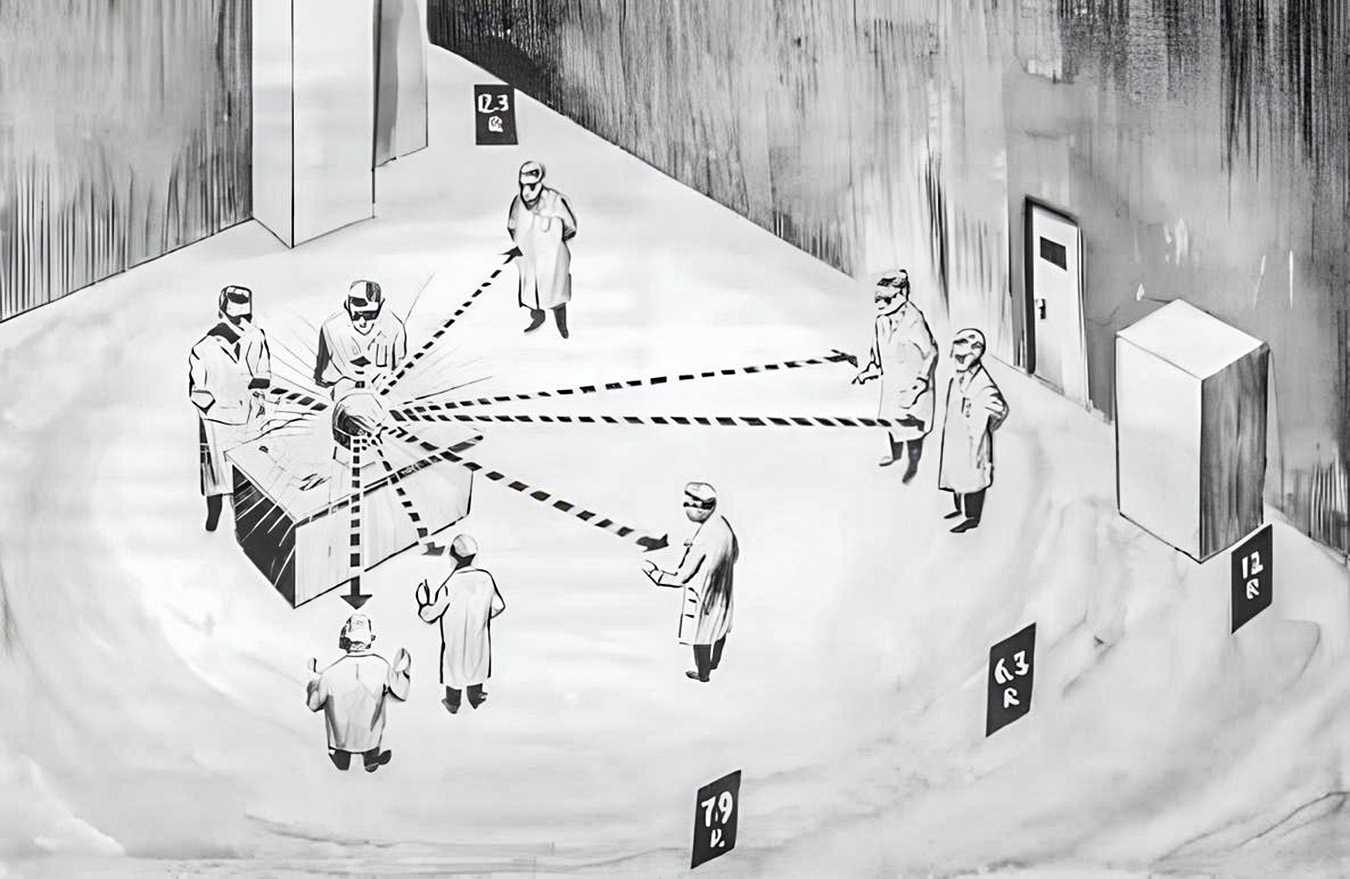

Harry served in two different groups at Technical Area 2 (TA-2), the Water Boiler Group, and the Critical Assembly Group. This area was also known as the Omega Site, which was used for nuclear criticality experiments.

Otto Robert Frisch served as the group’s leader. Daghlian was involved in the assembly of the Trinity Test’s core on July 16, 1945.

The First Person Died in a Nuclear Accident

Harry Daghlian was soon going to be the first person to die in a nuclear accident. The Critical Assembly Group had to figure out how various neutron reflectors affected the critical mass of plutonium. The efforts were referred to as tickling a dragon’s tail at Los Alamos. This label was coined by Richard Feynman.

9:00 p.m.

Harry Daghlian departed the customary Tuesday lecture at 9 o’clock p.m. on August 21, 1945, only a few weeks after the atomic bombs were detonated on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Daghlian intended to conduct experiments using a plutonium test core that evening for unclear reasons since these tests had been scheduled for the next day.

9:30 p.m.

Daghlian rolled into the Omega Site at about 9:30 p.m. that evening. Private Robert J. Hemmerly was stationed at Los Alamos as a “scientist in uniform” as part of the Special Engineering Detachment (SED) program.

The “Rufus” test core (the plutonium pit) was made up of two hemispheres of platinum, weighing a combined 13.7 lb (6.2 kg) and covered in a nickel coating around 100 μm (4 mils) thick. The plutonium had a density of 15.7 g/cm³. Daghlian arranged tungsten carbide blocks around the plutonium sphere to reflect the neutrons. Each cube weighed about 9.7 lb (4.4 kg).

9:55 p.m.

At 9:55 p.m., Daghlian used his left hand to lift the last block onto the superstructure. This block brought the overall mass of the reflector up to 520 lb, or 236 kg. Using the neutron counter, he found that the addition of this last block resulted in the supercritical superstructure.

He suddenly removed his hand, and the block tumbled down the middle of the superstructure. This resulted in a “prompt-supercritical” rise in neutron reflection, and things escalated quickly from there.

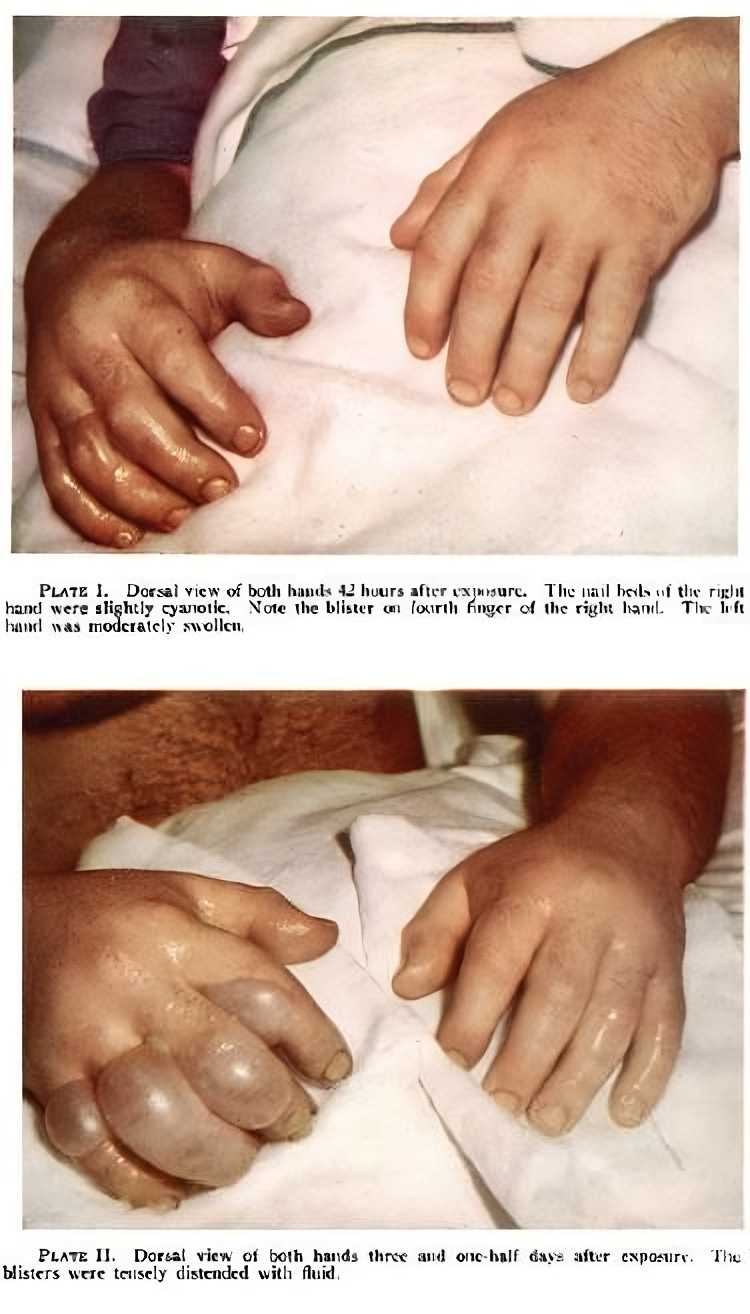

Daghlian now removed the block reflexively with his right hand, which was bathed in a blue light after the criticality event. Then he started taking the rest of the blocks apart.

While Hemmerly notified a sergeant, a student drove Daghlian to Los Alamos Hospital, where he arrived within half an hour. Daghlian’s hand was numb at first, but then he started to feel a tingling feeling. His health deteriorated rapidly as acute radiation syndrome took hold.

Harry Daghlian’s Death

Daghlian’s good buddy Louis Slotin would pay him regular visits to the hospital. Slotin was a member of Frisch’s team and a physicist with a Ph.D. Daghlian went into a coma just before passing away. At 4:30 p.m. on September 15, 1945, at the age of 24, he passed away from radiation poisoning (or radiation sickness) 25 days after the accident.

The Associated Press reported on September 21, 1945, in the New York Times that six days earlier, a “worker died from burns sustained in an industrial accident.” It wasn’t until 1956 that the true causes and timeline of the disaster were declassified as military secrets.

Daghlian received an estimated radiation dosage of 5.1 sieverts as a consequence of the event, which resulted in about 1016 nuclear fissions. On the other hand, Robert J. Hemmerly was also exposed to around 0.5 Sievert of radiation.

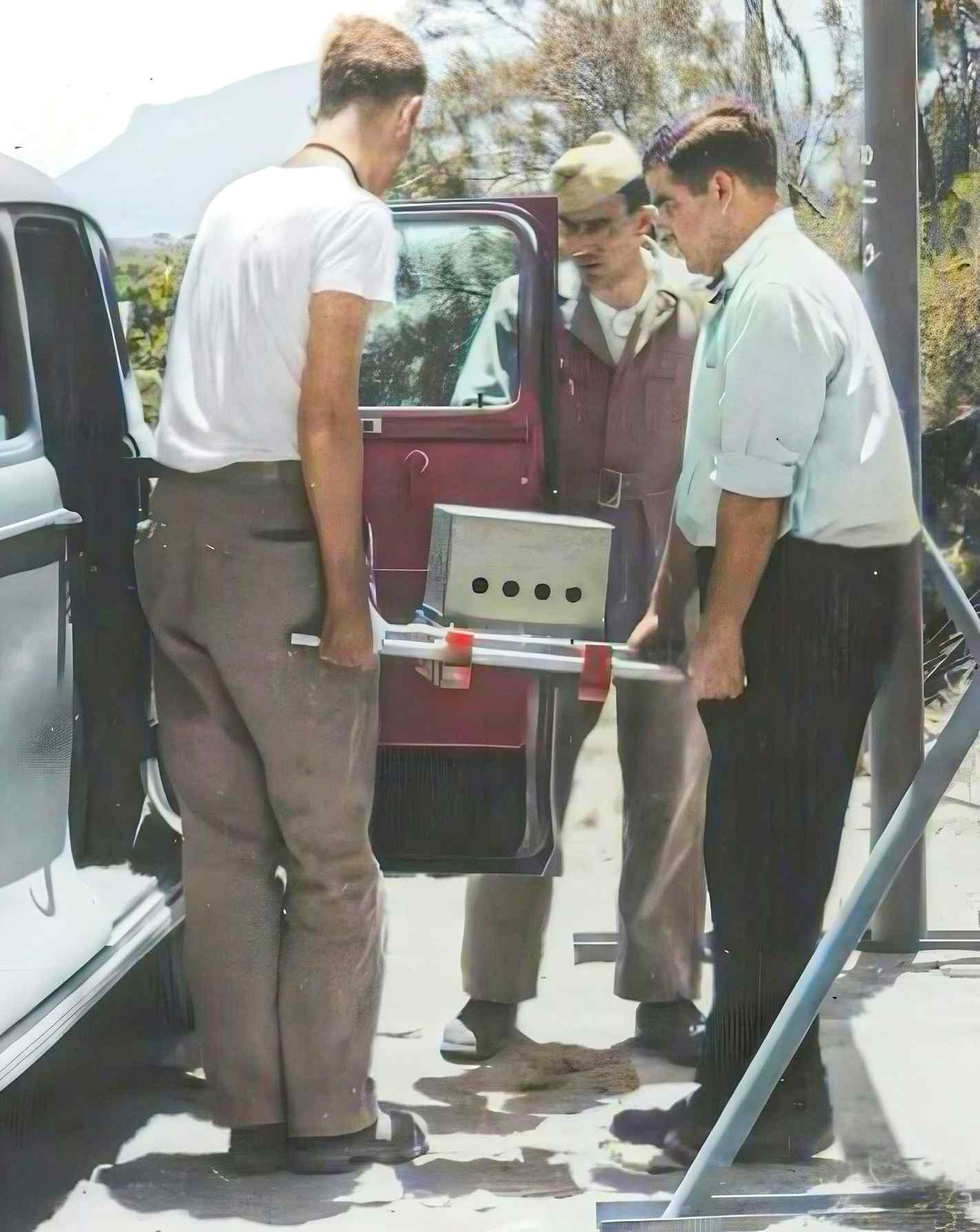

The accident did not damage the nickel layer around the plutonium core. The radioactive dosage emitted in the accident involving Daghlian was calculated on October 2, 1945, by reconstructing the incident at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Six times 1015 nuclear fissions were counted in this experiment. However, the scientists were never able to reach the prompt-supercritical state.

Louis Slotin performed an experiment with an identical plutonium hemisphere on May 21, 1946. Slotin was also accidentally exposed to radiation after slipping his screwdriver that he put between the beryllium and the core to keep them from interacting. A few days later, he died on May 30, 1946. “Demon Core” became the official moniker for this experimental core that took the lives of two scientists.

Legacy

Calkins Park in New London, Connecticut, is where a memorial stone and flagpole were set up in 2000 to remember Daghlian. The tombstone incorrectly reads “Daghiian” for his last name. The inscription on the memorial reads, “though not in uniform, he died in service to his country.”

In his novel The Alamos, Joseph Kanon fictionalized this event. In the movie Shadow Makers, Michael Merriman is based on Harry Daghlian.

A memorial honoring Daghlian was dedicated in New London, Connecticut on May 20, 2000.