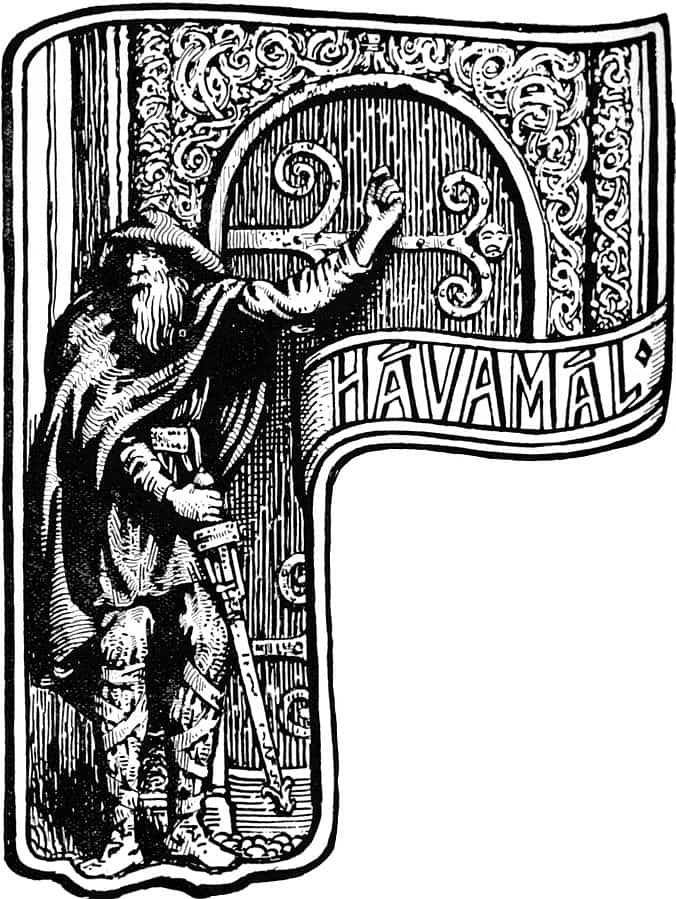

The Hávamál, the High Song or the Sayings of the High One, is a collection of a total of 164 eddic verses that are counted among the Poetic Edda. “High” in “The High Song” or “The Sayings of the High One” refers to the Norse god Odin, who in the poem gives mortal humans advice on how to lead a successful and honorable life. Hávamál, as part of the Edda, belongs to the wisdom literature and is compared to the Indian Vedas or the Homeric poems of Greece. The poem is exclusively preserved in the Codex Regius from the 13th century, which has been kept in the Arnamagnæan Collection in Reykjavík since 1971. In the Codex Regius, Hávamál is included as the second text directly after the Völuspá under the title hava mal, which indicates the high importance attributed to the poem by the compiler of the Codex Regius.

The fact that Snorri Sturluson places the first verse of Hávamál at the beginning of his mythological textbook Gylfaginning and that Eyvindr Skáldaspillir quotes verses of Hávamál at the end of his poem Hákonarmál is taken as evidence that Hávamál was already known in the 10th century. Klaus von See sees a series of dependencies on Latin poetry, especially the Disticha Catonis, whether directly or through the mediation of other Old Norse poems like the Hugvinnsmál, and also quotes other works that point to Seneca and other literature known in the Middle Ages.

Theodoricus Monachus, who wrote the Historia de antiquitate regum Norwagiensium in the 12th century, knew Plato, Chrysippus, Pliny, Lucan, Horace, Ovid, Virgil, the Church Fathers such as Origen, Eusebius, Jerome, and Augustine, and the late antique or medieval authors Boethius, Paulus Diaconus, Isidore of Seville, Bede, Remigius of Auxerre, Hugh of St. Victor, and Sigebert of Gembloux. This means that the Archbishop’s library in Nidaros was well stocked as early as the 12th century.

The earliest editions

In 1665, a very unreliable edition was published by Peder Hansen Resen, followed by editions in 1818 by Rasmus Christian Rask and Arvid August Afzelius, in 1828 by Finnur Magnússon, in 1843 by Franz Dietrich, and in 1847 by Peter Andreas Munch. The subsequent editions were based on Munch’s edition.

Content

Already in the 19th century, it was noted that the work was composed of several parts, with the number of parts and their boundaries being disputed. Hazelius assumed five parts, Müllenhoff apparently assumed six parts in 1883, and Finnur Jónsson in his monograph Hávamál (Copenhagen 1924) even assumed seven parts. The subheadings Ládfafnismál (“Loddfafnir’s Song”, verses 111–138), Rúnatal þáttr Óðinn (“Odin’s Rune Song”, verses 139–142), and Ljóðatal (“Magic Songs”, verses 147–165) are not found in the manuscript. Today, some scholars assume a division into three parts: Part I (verses 1–76), Part II (verses 78–110), and Part III (verses 111–165). According to this classification, the first part ends with the famous verse:

“Deyr fę,

deyia frǫndr,

deyr sialfr it sama;

ec veit einn

at aldri deýr:

domr vm dꜹþan hvern.”Cattle die,

kinsmen die,

all men are mortal;

but words of praise will never perish

nor a noble name.

Here, some have wanted to see Christian echoes, as a similar train of thought can be found in Ecclesiastes 3:19. However, not everything that is similar must depend on each other.

In terms of content, the first two (of three assumed) parts deal with wisdom for life and rules of conduct. The parts differ in that in the first part, all possible topics are addressed and consistently described in the verse form Ljóðaháttr, while the teachings of the second part focus on wealth and gender relations. Klaus von See identifies the first-person narrator, who reports on his own views and experiences in some verses, quite naturally with Odin for the entire poem. Ottar Grønvik, on the other hand, sees him as an authorial narrative poet who reports on his development and also serves as a representation of people in relation to the divine. However, at one point in the first part, it is clearly Odin. The poet critically distances himself from Odin when he reduces Snorri’s Skáldskaparmál’s celebrated acquisition of poetic mead to a simple drinking spree.

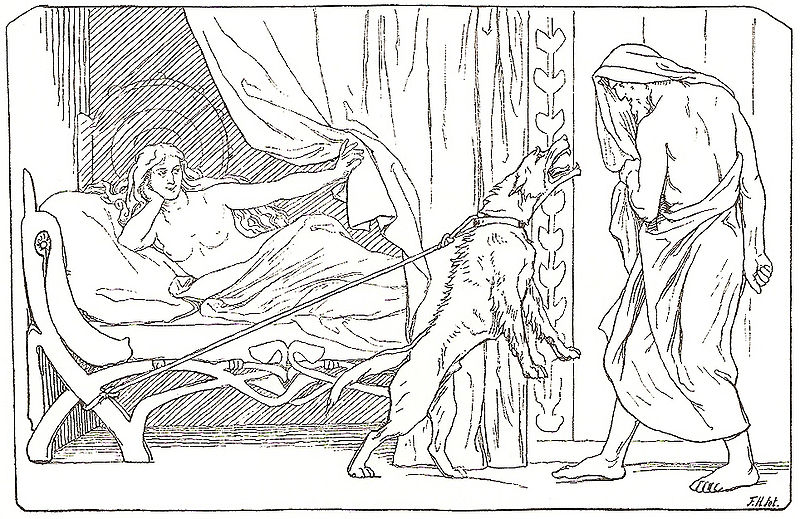

The second part differs from the first part formally in that between the verses in the verse form of Ljóðaháttr, there are also simple list verses, e.g., verses 84–86. Practical advice, such as in verses 80–82, is also missing in the first part. They could be of a later date, but verse 80 must be very old, as it advises to praise a woman only after she has been cremated. The verse probably dates from the time of cremation. The same applies to verse 70. In the second part too, there are references to Odin that portray the god in an unfavorable light. In the first, Odin recounts the embarrassing failure of a forbidden love affair (verses 95–101). This passage is probably old because in verse 96, the word “Jarl” is used as the highest social position, indicating the pre-monarchical era. The second Odin story (verses 104–110) depicts Odin as a ruthless and immoral god. The ice giants inquire about “Bölverkr” in verse 109, which means evildoer. Here, too, Odin is not portrayed as a positive hero. In the past, Odin’s denigration was seen as having Christian influence. Today, it is assumed that there were not only tensions between paganism and Christianity but also within paganism between different cults. However, the poet was not irreligious, as verse 79 shows, in which he attributes the holy runes to the gods. Due to his moral standards, which he applies to Odin’s behavior, the poet can, with some probability, be assigned to the peasant religion of Thor and Freya.

The much-discussed verse 111 introduces the teachings of Loddfafnir:

Mál er at þylja

It’s time to speak

þular stóli á

Urðarbrunni at,

sá ek ok þagðak,

sá ek ok hugðak,

hlýdda ek á manna mál;

of rúnar heyrða ek dæma,

né of ráðum þögðu

Háva höllu at,

Háva höllu í,

heyrða ek segja svá:

from the seat of the speaker. (Þulr).

At the Well of Urd

I sat and was silent,

sat and pondered,

listened to the speech of men;

about runes I heard them speak,

and they did not withhold counsel

in the hall of the High One;

in the hall of the High One

I heard such things said:

The last verse of the Hávamál picks up this formulation, so it can be assumed that originally only this part between these framing stanzas bore the name Hávamál and was an independent poem.

The discussion revolves around the person of the “Þulr” (speaker) in the second line, which is often identified with Odin. Karl Müllenhoff, however, demonstrated through usage examples also in Old English that Þulr is a human speaker in the king’s hall, a powerful man. Therefore, he changed “manna mál” in line 6 to “Háva mál”. According to his view, the first-person narrator is a human speaker on the speaker’s chair who reports to the people what he heard at Urd’s Well, where Odin himself instructed him and addressed him as “Loddfafnir.” He refers to him as a rogue because in verse 113, he pretends Odin advised him not to get up at night unless he needed to urinate or was assigned as a guard. Müllenhoff dismisses verse 112 as a later addition. He was essentially followed by Finnur Jónsson. Sophus Bugge kept the text and interpreted verses 111ff. so that Loddfafnir sits on the speaker’s chair and announces to those present the religious revelation he received from Odin and initiated men about Odin’s self-sacrifice (verse 139). According to him, Loddfafnir is not a real person but a mythical-poetic figure. Axel Olrik saw a connection between the magical framework of the sorcerers (Seiðhiall) and the chair of the Þulr and considers the chair to be a magical prop. W. H. Vogt then emphasized the relationship between Völva and Þulr. He sees the high seat of the Völva and the poet’s chair of the Þulr on the same level.

A particular difficulty is that the Þulr is said to have received his revelation both at Urd’s Well and in the hall of the High One, which is commonly equated with Valhalla. However, both places were thought of as far apart in Norse mythology: Valhalla with the gods and Urd’s Well under the world tree Yggdrasil. A newer interpretation resolves this contradiction by suggesting that the hall of the High One is not Valhalla but a cult house dedicated to Odin and Urd’s Well is one of the sacred springs in close proximity. This assumes that there was originally no internal connection between the first two parts and the concluding third part, so that the designation “the High One’s Hall” in the last Odin adventure of the second part (verse 109), which clearly refers to Valhalla, cannot be transferred to the third part. The runes that the men speak of may be certain mystical-religious chants, as they are also referred to as runes in Vafþrúðnismál verse 42.

The name “Loddfáfnir” is composed of the two word stems “Lodd” and “favne” and a suffix -nir (e.g., Vafþrúðnir, Fjósnir in verse 12 of the Rígsþula and more), which was common at the time. “Lodd” poetically stands for “woman” and “fáfnir” is traced back to “faðmr”, “to embrace”. *Faðmnir is the Embracer and Loddfáfnir “he who embraces the woman”. From the immediately following stanzas, which deal with marital fidelity, one can imagine an honest man who passes on the firm moral norms of the peasant society, which he heard in the hall. This leads to verse 139:

Veit ek, at ek hekk

vindga meiði á

nætr allar níu,

geiri undaðr

ok gefinn Óðni,

sjalfr sjalfum mér,

á þeim meiði,

er manngi veit

hvers af rótum renn.I know that I hung on a windy tree

nine long nights,

wounded with a spear, dedicated to Odin,

myself to myself,

on that tree of which no man knows from where its roots run.

The last two lines are considered a later addition because they adopt the description of Yggdrasil under the name “Mímameiðr”, from which no one knows which root it grows from. Here, however, it is a sacred sacrificial tree on earth, to which the remark does not apply because no one knows where it is located.

The spear was Odin’s weapon and it played a special role in the sacrifice. With it, the sacrifice was wounded as a sign that it was dedicated to Odin. Adam of Bremen writes in his Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum about the sacrificial ceremonies in Uppsala, stating that they lasted for nine days and that each day a man was hanged on the sacrificial tree. The ritual sacrifice described in verse 139 would have taken place at the beginning of such sacrificial ceremonies, and the first sacrifice hung on the tree for as long as the celebration lasted. However, the first two lines of the following verse indicate that the Hávamál was not an ordinary fertility sacrifice:

Við hleifi mik sældu

né við hornigi;

nýsta ek niðr,

nam ek upp rúnar,

æpandi nam,

fell ek aftr þaðan.No bread did they give me nor a drink from a horn,

downwards I peered;

I took up the runes,

screaming I took them,

then I fell back from there.

The one sacrificed was not hung by the neck to die, but by the body, so that he could peer downward, and thus he acquired the runes. Learning by loudly speaking the material was the customary method of instruction at that time. By “runes” are meant the religious secrets and magical knowledge in fixed mnemonic verses, and they contrast with the bread and livestock of the fertility sacrifice. The image of the hanged sacrifice may also be described in verse 135:

oft ór skörpum belg

skilin orð koma

þeim er hangir með hám

ok skollir með skrám

ok váfir með vílmögum.From shriveled skin

often comes wise word,

(of) the one who hangs with hides

and dangles among animal skins

and floats alongside sons of misfortune.

In Vestfold, remnants of a tapestry were found depicting nine men hanging from a tree. It is believed that Odin is speaking here. Sophus Bugge saw Christian influence in this, assuming a parallel to the crucifixion of Christ. This view was also recently supported by Britt-Mari Näsström. However, it contradicts the fact that the Bible does not speak of a sacrifice of God to himself but of the redemptive suffering of Jesus, who is a person of God distinct from the Father. Grønvik therefore assumes that it is not Odin but the Þulr from verses 111 and 112, who is the first-person narrator, experiencing a mystical union with Odin in ecstasy, as described for mystics in many religions. This mystical union with Odin simultaneously constitutes an initiation rite for a Þulr, as has been suggested earlier. It follows the notion that Odin hung in the World Ash Yggdrasil in mythical times. Yggr is one of Odin’s many names.

Grønvik believes to have found hints on the runestones of individuals referred to as Þulr. On the Snoldelev Stone from Zealand, it says, “Gunvald’s stone, son of Roald, tul in Salhauku(m)” (= Salløv).

Ethics

The philosophy of the poem is rooted in the belief in the worth of the individual, who nonetheless is not alone in this world but connected through an inseparable bond with nature and society. The cycle of life is complete and indivisible. The animate world, in all its manifestations, forms a harmonious whole. Violations against nature have immediate repercussions on the individual themselves. Each individual is responsible for their own life, happiness or unhappiness, and creates their own life from their own resources.

References

- Konstantin Reichardt: “Odin on the gallows.” Yale University, 1957, pp. 15–28.

- Kalus von See: The figure of Hávamál. A Study of Eddic Saying Poetry. Athenäum Verlag 1972.

- Barend Sijmons and Hugo Gering: The Songs of the Edda. Third volume: Commentary. First half: Songs of the Gods. 1927.

- Kieran R. M. Tsitsiklis: The Thul in Text and Context. Þulr/Þyle in Edda and Old English Literature. Berlin/Boston 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-045730-8.