The French Revolution of 1789 is famous for its ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. However, amidst the euphoria of political change, the revolution also witnessed a series of dark and harrowing events that left an unforgettable mark on history. Beyond the lofty goals and inspiring slogans, the period known as the French Revolution witnessed an unprecedented wave of violence, chaos, and persecution that scarred the nation and its people.

- The Reign of Terror: Bloodshed and the Guillotine

- The September Massacres: Carnage in Paris Prisons

- The War in the Vendée: A Brutal Civil War

- The Lyon Massacres: “Lyon made war on liberty: Lyon is no more!”

- The Noyades of Nantes: Drownings in the Loire River

- The Law of Suspects: Accusations and Arrests

- The Destruction of Vendeans at Savenay: A Massacre in the Snow

- The Destruction of Hébertists and Dantonists: Political Purges

- The Execution of King Louis XVI: A Regicide in History

- The Cult of the Supreme Being: Dechristianization Campaign

- The Conspiracy of Equals: Failed Utopian Revolt

From the infamous Reign of Terror and mass executions by guillotine to lesser-known but equally shocking events such as the Witch Hunts and the Noyads of Nantes, you can learn about the darkest moments of this turbulent period. These events are a chilling reminder that even in the pursuit of justice and freedom, man’s capacity for brutality and bloodshed knows no limits.

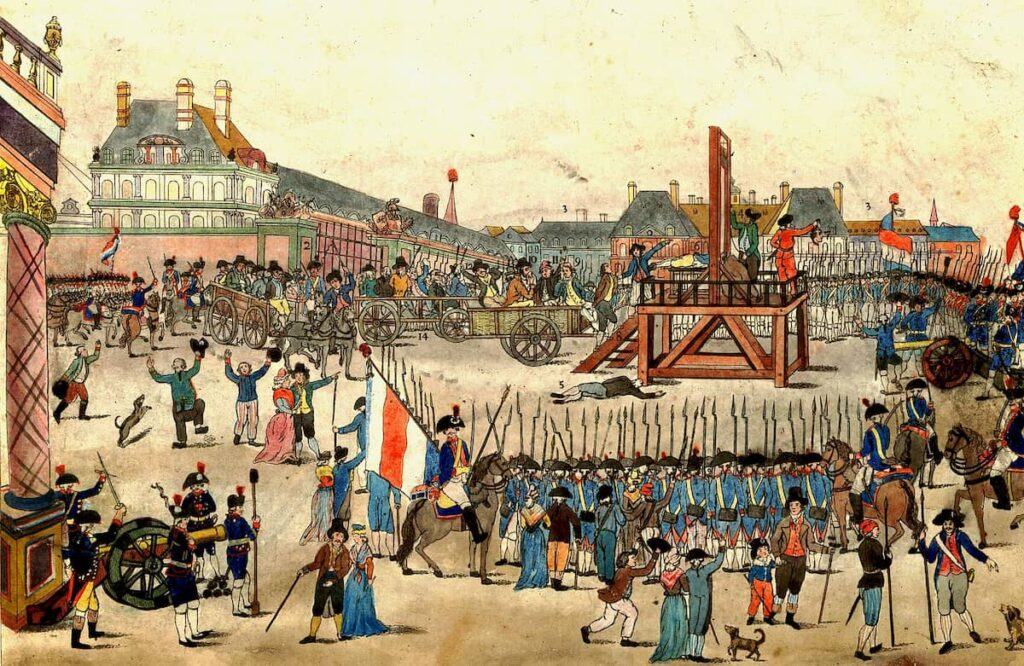

The Reign of Terror: Bloodshed and the Guillotine

There are two distinct phases that make up the Terror, a haunting period of the French Revolution. The first Terror unfolded between August 10 and September 20, 1792, as revolutionary forces aimed to quell any opposition that sought to restore the monarchy. The ruling Paris Commune introduced radical measures, resulting in the suspension of the king, arrests, the establishment of an extraordinary tribunal, and the exile of non-compliant priests.

This phase included the notorious September Massacres, during which over 1,000 individuals, including nobles, clergy, journalists, and deputies, met a violent end. The first Terror came to a close with France’s victorious defense against the Prussian invasion at Valmy on September 20, 1792.

The second Terror, initiated on September 5, 1793, marked a more pervasive and ruthless era. Driven by the need to address multiple threats to the Revolution, such as war, civil conflict in Vendée, economic crises, and political divisions, the Convention decided to prioritize “putting terror on the agenda.” The Montagnards, a radical faction led by Robespierre, assumed control of the Convention, culminating in the removal of the moderate Girondins in May 1793. Robespierre presented himself as the champion of virtue and the people’s sovereignty, employing committees like the Committee of Public Safety and the Revolutionary Tribunal to hunt down and eliminate “counter-revolutionaries.”

Law of Suspects broadened the criteria for suspicion, while the Law of 22 Prairial Year II expedited trials and denied the right to defense. In Paris and the provinces, thousands faced execution. The Terror extended beyond politics into a campaign of “dechristianization,” suppressing Catholicism and introducing Temples of Reason. Robespierre’s fall on 9 Thermidor Year II (July 27, 1794) signaled the end of the Terror and the Committee of Public Safety’s dictatorship, giving way to a more moderate period known as the Directory.

The legacy of the Terror is a complex and contentious matter. Approximately 17,000 were guillotined, and another 25,000 met their end through different means during this period.

The September Massacres: Carnage in Paris Prisons

The September Massacres were a series of summary executions that occurred from September 2 to September 6, 1792, during the French Revolution. Approximately 1,600 lives were claimed in Paris and the provinces, including those of priests, nobles, journalists, Swiss officers, and common criminals. The massacres were a result of popular panic, driven by the fear of an aristocratic conspiracy and the threat of foreign invasion.

These events took place in the midst of a political, social, and military crisis during the revolution. The monarchy was overthrown in August 1792, and King Louis XVI and many suspects were imprisoned. Concurrently, France was at war with European powers seeking to restore the French monarchy. The fall of Verdun on September 2 heightened the fear in Paris as rumors circulated that prisoners were planning an uprising. Posters, newspapers, and speeches called for popular justice, leading groups of sans-culottes to head to the prisons, where improvised tribunals sentenced most detainees to death.

The victims, regardless of gender, age, or social status, were beheaded, stabbed, or mutilated. The violence extended to various prisons and provinces, resulting in hundreds of deaths. The September Massacres were a bloody and authoritarian episode of the French Revolution, reflecting social and political tensions as well as the desire to defend the Revolution against its enemies.

The outcomes of these massacres are subject to debate, with some condemning them as crimes against humanity, others justifying them as a historical necessity, and still others comparing them to violence in other revolutions or regimes. The September Massacres continue to raise questions about the limits of political violence and the essence of the French Revolution.

The War in the Vendée: A Brutal Civil War

The War in the Vendée, spanning from 1793 to 1796, was a series of armed uprisings in western France. This conflict pitted royalist and Catholic peasants against republican revolutionary forces. It’s considered by some to be a genocide, claiming nearly 200,000 lives. The war’s causes were rooted in economic, social, political, and religious factors. The impoverished Vendée peasants, loyal to their Catholic faith, opposed revolutionary measures such as taxing them and subjecting priests to the Republic. The conscription of 300,000 men to fight against European monarchies triggered the rebellion in 1793.

Divided into three phases, the war saw early Vendée victories, a shift in power to the republicans, and a brutal crackdown leading to the Vendée’s eventual defeat. The conflict ended in 1796 with the Treaty of La Jaunaye, resulting in the deaths of nearly 200,000 people, devastating the region, and leaving lasting historical and political debates surrounding its classification as a “genocide.

The Lyon Massacres: “Lyon made war on liberty: Lyon is no more!”

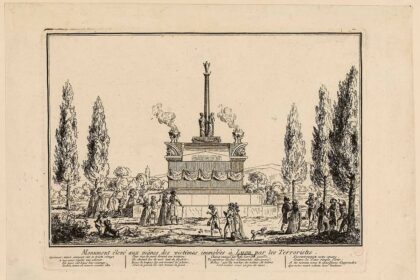

The Lyon Massacres (Siege of Lyon), a brutal chapter during the Reign of Terror in the French Revolution, unfolded in Lyon between October 1793 and April 1794. The National Convention, the revolutionary government, ordered the violence and destruction as retaliation for the city’s defiance. The death toll is uncertain, but is estimated at around 2,000. The conflict’s origins trace back to political divisions arising from the 1789 Revolution, pitting Girondins (moderates supporting a constitutional monarchy) against Montagnards (radicals favoring the Republic). Lyon declared itself in insurrection, refusing to acknowledge the National Convention. In response, the Convention sent a massive army, laying siege to Lyon. After a grueling resistance, Lyon eventually capitulated in October 1793.

In a punitive move, the National Convention decreed the destruction of Lyon, renaming it “Ville-Affranchie” and imposing strict measures. Representative Joseph Fouché initiated a ruthless crackdown, establishing revolutionary tribunals that doled out death sentences without fair trials. Victims included people of all backgrounds, from nobles and priests to ordinary citizens, women, children, and foreigners. Many were executed, and historic buildings were demolished. The Lyon Massacres continued until the fall of Maximilien Robespierre in 1794, which marked the end of the Reign of Terror. A more moderate approach, amnesty, and city reconstruction followed, ultimately restoring Lyon’s name. The Lyon Massacres remain a tragic and deadly episode in the French Revolution’s history, stirring debates on the nature and boundaries of revolutionary violence.

The Noyades of Nantes: Drownings in the Loire River

The Nantes Drownings, also known as “Noyades de Nantes,” occurred during the French Revolution from October 1793 to April 1794. Jean-Baptiste Carrier, a representative on a mission for the National Convention, ordered a series of summary executions. The victims, numbering between 1,800 and 4,860, included Vendéens and Chouans who opposed the republic, as well as various other individuals.

The context of these drownings was the ongoing civil war in western France between royalist peasants and republican forces. The revolutionary government, fearing the war’s threat to national security, adopted a policy of Terror to eliminate enemies. Carrier, aiming to make Nantes an example, resorted to drownings as a faster and more cost-effective means of execution.

Victims included combatants, priests who rejected the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, nobles, citizens, women, children, and foreigners. Politically, the Nantes Drownings contributed to discrediting the Reign of Terror and played a role in Robespierre’s fall. Carrier was arrested and executed for crimes against humanity. Socially, the drownings brought immense suffering and trauma to the region’s residents and victims’ families.

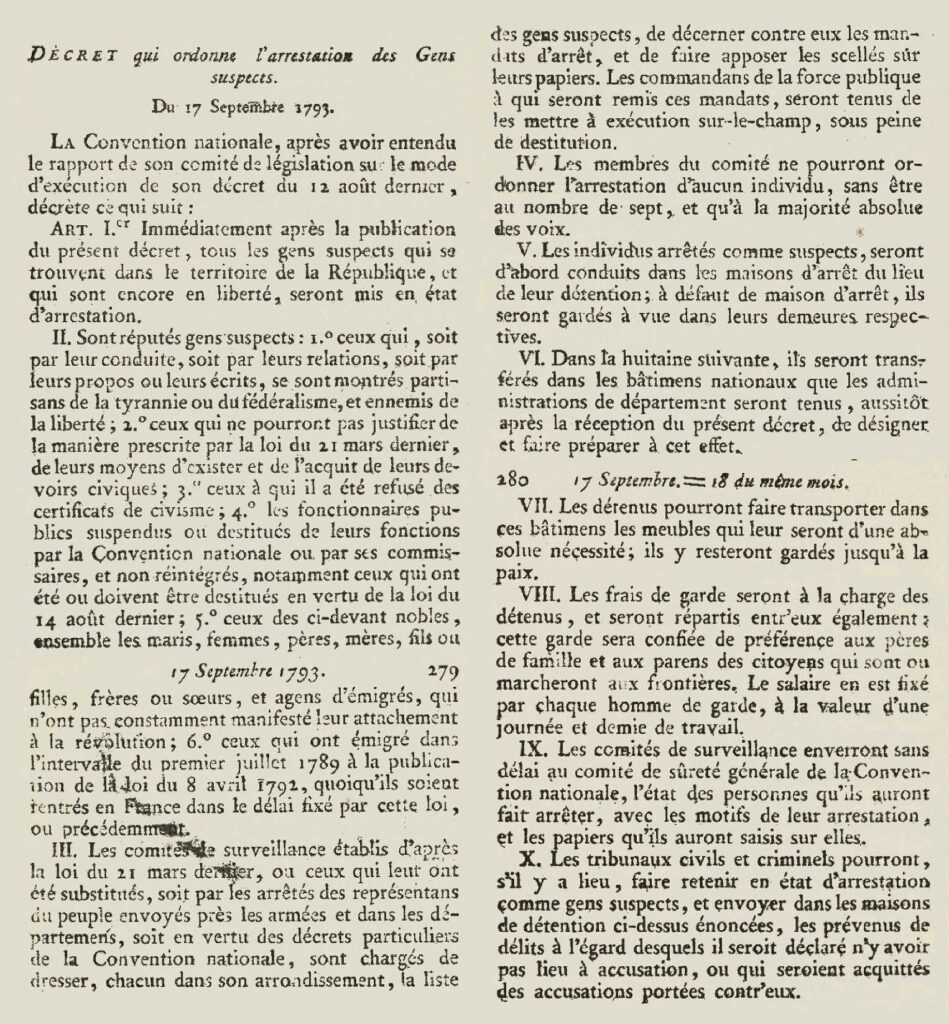

The Law of Suspects: Accusations and Arrests

During the height of the Reign of Terror, the National Convention passed the Law of Suspects on August 12, 1793, allowing for the arrest and trial of anyone considered an enemy of the French Revolution. A decree issued on September 17, 1793, added to it by broadening the definition of suspects and the procedures for their arrest.

The reasons behind the Law of Suspects were linked to the context of civil war and foreign war threatening the nascent Republic. Faced with the revolt of the Vendéens and federalists who supported monarchy and the Catholic religion and the coalition of European powers seeking to restore the Old Regime, the revolutionary government adopted a policy of Terror aimed at eliminating all opponents, real or perceived, to the Revolution. The Law of Suspects was one of the instruments of this policy, relying on surveillance committees, revolutionary tribunals, and the Committee of Public Safety.

The provisions of the Law of Suspects were inspired by Robespierre’s desire, as the primary leader of the Reign of Terror, to uphold republican virtue and purify society from corrupt elements. The law allowed for the arbitrary arrest of anyone who had “not consistently demonstrated their attachment to the Revolution” or who had “done nothing against liberty and nothing for it.”

The Destruction of Vendeans at Savenay: A Massacre in the Snow

The Battle of Savenay is the name given to the confrontation that took place on the 22nd and 23rd of December 1793 between republican troops and Vendéen insurgents during the Vendée War. This battle, which occurred in Savenay, in the Loire-Atlantique region, marked the end of the Virée de Galerne, a bold expedition by the Vendéens across France, and resulted in the defeat and annihilation of the Catholic and royalist army.

The causes of the battle of Savenay are tied to the context of the Vendée War, an armed peasant revolt in western France, loyal to the monarchy and the Catholic religion, against the revolutionary government that imposed taxes, requisitions, and religious persecution on them. After winning several victories against republican forces, the Vendéens, led by commanders such as La Rochejaquelein, Charette, Bonchamps, Lescure, and d’Elbée, decided to cross the Loire in October 1793 to join the royalists in Brittany and Normandy and seek assistance from the English. This venture, known as the Virée de Galerne, ended in failure as the Vendéens did not find the expected support and were harassed by the reorganized republican army. The Vendéens had to turn back and attempt to return to Vendée, passing through Savenay.

The republicans’ determination to put an end to the Vendéen rebellion and set an example influenced the outcome of the Battle of Savenay. The republicans, under the command of generals Kléber, Marceau, and Westermann, had 18,000 well-equipped and disciplined soldiers, compared to only 6,000 Vendéens. The republicans surrounded the Vendéens in Savenay and engaged them in a merciless battle on December 23, 1793. The battle turned into a massacre as the republicans showed no mercy to the Vendéens, whom they considered “brigands.” The Vendéens were killed on the battlefield or executed after capture. Among the victims were several Vendéen leaders like d’Elbée, Fleuriot, and Sapinaud.

The consequences of the Battle of Savenay were both military and political. Militarily, it marked the end of the Virée de Galerne and the first phase of the Vendée War. It led to the destruction of the Catholic and royalist army, with around 4,000 casualties, and the dispersion of survivors who sought refuge in the woods and marshes. It allowed the republicans to regain control of the territory and prepare for the following bloody repression with the “infernal columns.” Politically, the battle of Savenay contributed to strengthening the Reign of Terror, which aimed to eliminate the enemies of the Revolution through force and law.

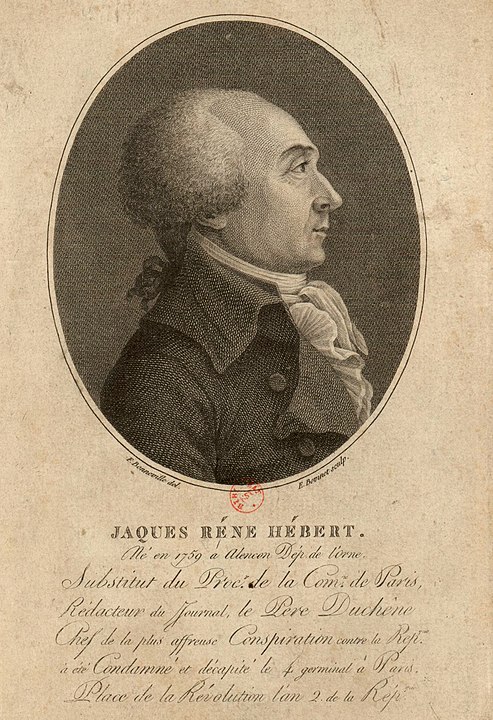

The Destruction of Hébertists and Dantonists: Political Purges

The Hébertists and Dantonists were two distinct groups within the radical faction of the French Revolution. The Hébertists, under the leadership of Jacques Hébert, were well known for their extreme revolutionary fervor and anti-religious stance. They played a significant role in the dechristianization campaign, advocating for the deconstruction of religious symbols and practices.

On the other hand, the Georges Danton-led Dantonists initially belonged to the more moderate Jacobin faction but later changed their views. They were associated with the Committee of Public Safety and played a role in the implementation of the Reign of Terror.

The downfall of these groups can be attributed to several factors:

- Both the Hébertists and Dantonists had internal divisions and conflicts, which weakened their cohesion.

- Maximilien Robespierre, a key figure in the Committee of Public Safety, sought to consolidate his power and viewed the Hébertists and Dantonists as threats to his authority.

- France was facing severe economic and political challenges during this period, and the radicalism of the Hébertists and Dantonists was increasingly seen as a destabilizing factor.

- The radicalism and extremism of these groups alienated public opinion, leading to a growing desire for more moderate governance.

In March 1794, Robespierre and his allies in the Committee of Public Safety initiated a purge of the Hébertists and Dantonists. They detained a number of their leaders, including Hébert and Danton, and ultimately put them to death by guillotine. This marked the end of the radical phase of the Revolution, as Robespierre’s faction tightened its grip on power.

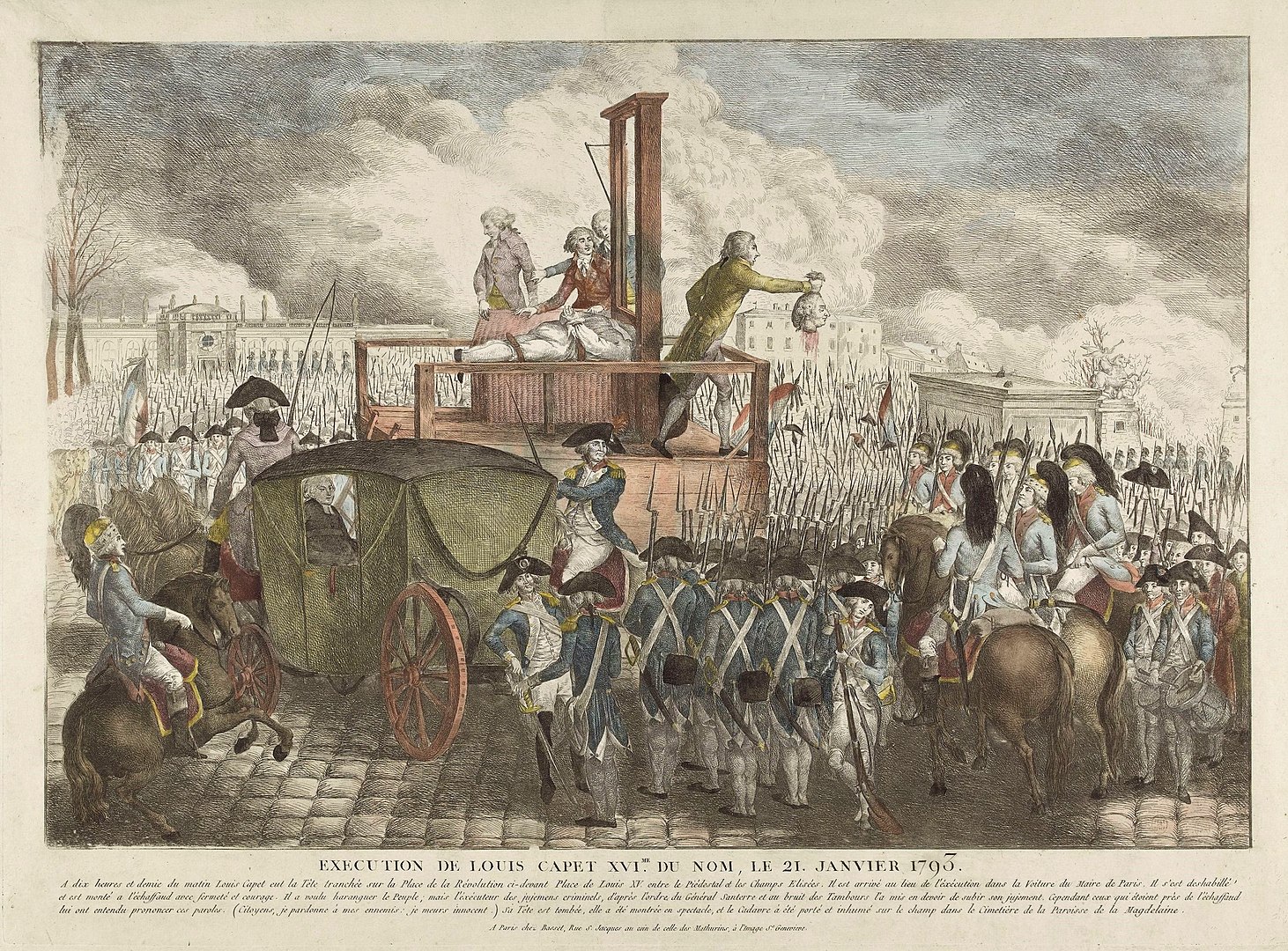

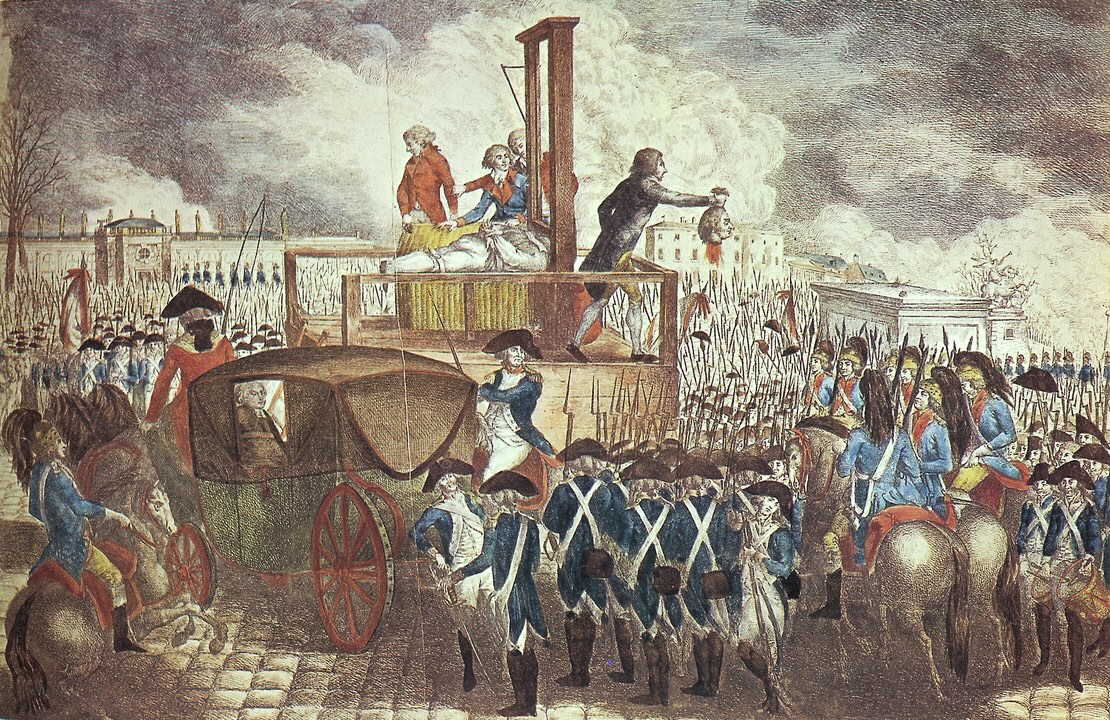

The Execution of King Louis XVI: A Regicide in History

The execution of Louis XVI is the name given to the event that ended the life of the King of France on January 21, 1793, at the Place de la Révolution in Paris. This execution, the result of a controversial trial, marked a significant turning point in the history of the French Revolution and had significant political, social, and memorial consequences.

The causes of Louis XVI’s execution are linked to the context of civil war and foreign war threatening the nascent Republic. Faced with the uprising of the Vendéens and federalists who supported the monarchy and the Catholic religion, as well as the coalition of European powers aiming to restore the Ancien Régime, the revolutionary government adopted a policy of Terror, seeking to eliminate all opponents, real or perceived, to the Revolution. The king, who attempted to escape to Varennes in June 1791, was considered a traitor and an enemy of the nation. He was removed from his duties and imprisoned at the Temple prison under the name “Louis Capet.”

The manner of Louis XVI’s execution was inspired by Robespierre’s desire, the primary leader of the Reign of Terror, to establish republican virtue and purify society from corrupt elements. The king was tried by the National Convention, the legislative assembly elected by universal male suffrage. The trial lasted from December 11 to December 26, 1792, and focused on three charges: conspiracy against public liberty, attempted escape, and complicity with foreign powers.

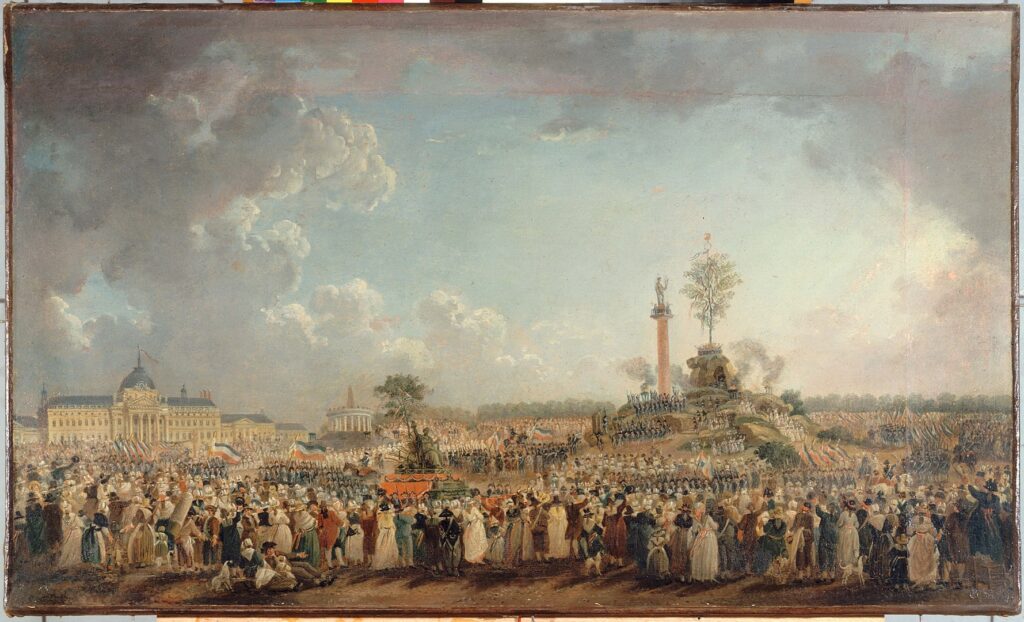

The Cult of the Supreme Being: Dechristianization Campaign

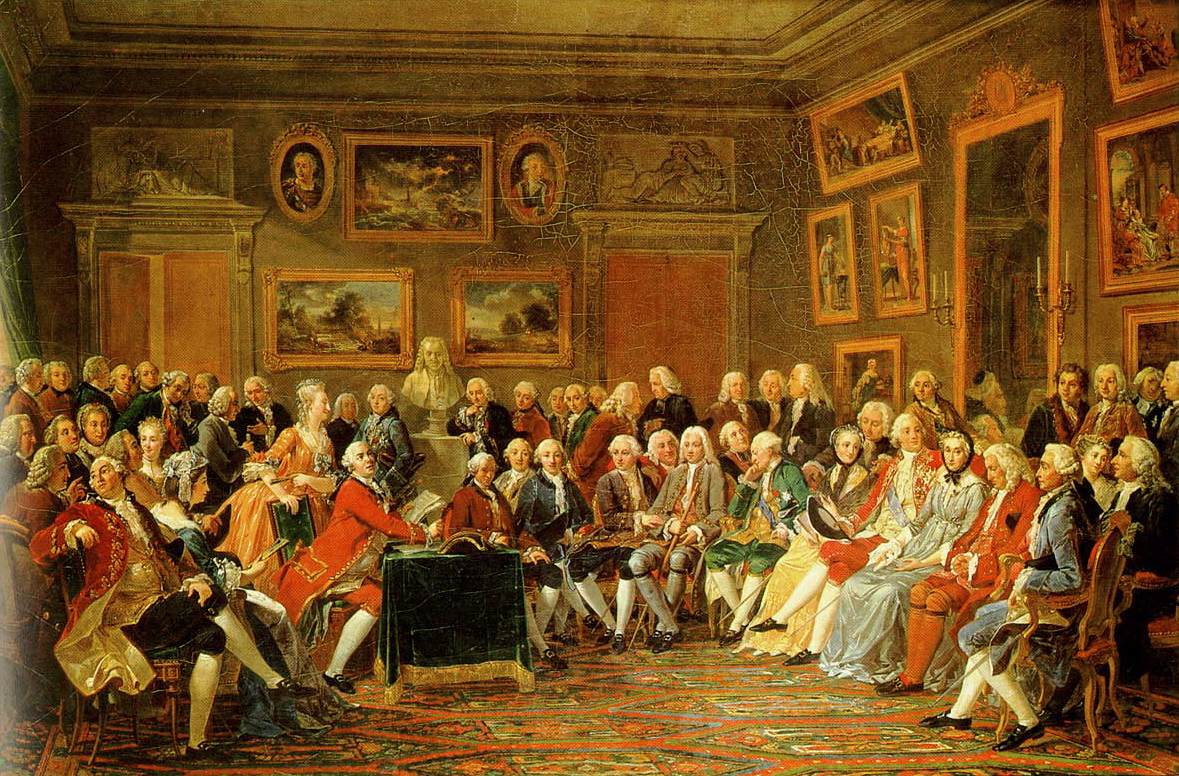

The Cult of the Supreme Being, established by Robespierre during the Reign of Terror in May 1794, aimed to infuse the French Revolution with a religious and moral dimension grounded in the acknowledgment of God and the immortality of the soul. It was a response to the civil war and foreign threats endangering the Republic. Robespierre, driven by the belief in virtue as the Republic’s fundamental principle, sought a metaphysical foundation for the policy of Terror. Inspired by Rousseau’s philosophy, he opposed atheism, which he considered aristocratic and barbaric, as well as the excesses of the Cult of Reason. Robespierre’s desire to promote republican virtue and cleanse society of corruption shaped the specifics of the Supreme Being cult.

The cult’s declaration on May 7, 1794, established its principles and set the stage for decadary festivals, replacing Christian Sundays, celebrating various Revolutionary entities and virtues. The first Supreme Being festival took place on June 8, 1794, featuring symbolic ceremonies, parades, and celebrations in Paris and across the country. However, the cult of the Supreme Being had profound political, social, and memorial consequences. It marked the peak of Robespierre’s influence but also contributed to his downfall as he made many enemies. The cult triggered reactions from European powers, uprisings by royalists, and intensified the Reign of Terror.

On a social level, it led to the execution of the king and numerous individuals, impacting people’s daily lives with calendar changes, currency alterations, and shifts in fashion.

The Conspiracy of Equals: Failed Utopian Revolt

The Conspiracy of the Equals, orchestrated by Gracchus Babeuf and his followers between 1795 and 1797, aimed to overthrow the revolutionary government during the Directory era and establish a communist society founded on equality of property and rights. This marked the first attempt at a social revolution in Europe but was thwarted, leading to Babeuf and his associates’ arrest, conviction, and execution.

The conspiracy’s origins were intertwined with the civil war and foreign threats challenging the young Republic, prompting the revolutionary government to employ the Terror policy to eliminate opposition. In the Manifesto of the Equals, Babeuf called for social equality, condemning the rich-poor divide and urging a popular uprising to abolish private property. The conspiracy sought to transform communism into a reality, relying on key figures and mobilizing support through Babeuf’s newspaper, “Le Tribun du Peuple.”

The plan was to seize strategic Parisian locations, proclaiming the “Republic of Equals” and establishing a temporary revolutionary dictatorship in preparation for the “administration of things” and communal property and labor. The consequences of the Conspiracy of the Equals encompassed political, and social dimensions. The trial of the conspirators unfolded in 1797, with Babeuf and Darthé sentenced to death. Socially, it reflected the working classes’ discontent and aspirations, foreshadowing 19th-century socialist and communist movements.