The Mosaic Map of Madaba (also known as the Madaba Mosaic or Madaba Map) is a fragmentarily preserved late antique to early Byzantine floor mosaic located in the modern Greek Orthodox Church of St. George in Madaba, Jordan. The Madaba Mosaic is the oldest surviving original cartographic depiction of Palestine on both sides of the Jordan River and Lower Egypt. It was created after 542, possibly during the reign of Emperor Justinian († 565).

The Madaba Map is renowned for its detailed representation of the city of Jerusalem, including walls, gates, main streets, and churches. Other cities, such as Ashkelon and Gaza, are similarly depicted in detail. The Madaba Map also contains some information about economic life: dates and balsam are cultivated in the Jericho area, and transport ships ply the waters of the Dead Sea. Pilgrimage tourism to Palestine was a significant economic factor in the 6th century, with the map featuring mostly biblical pilgrimage sites, supplemented by the stations of the overland roads that connected them.

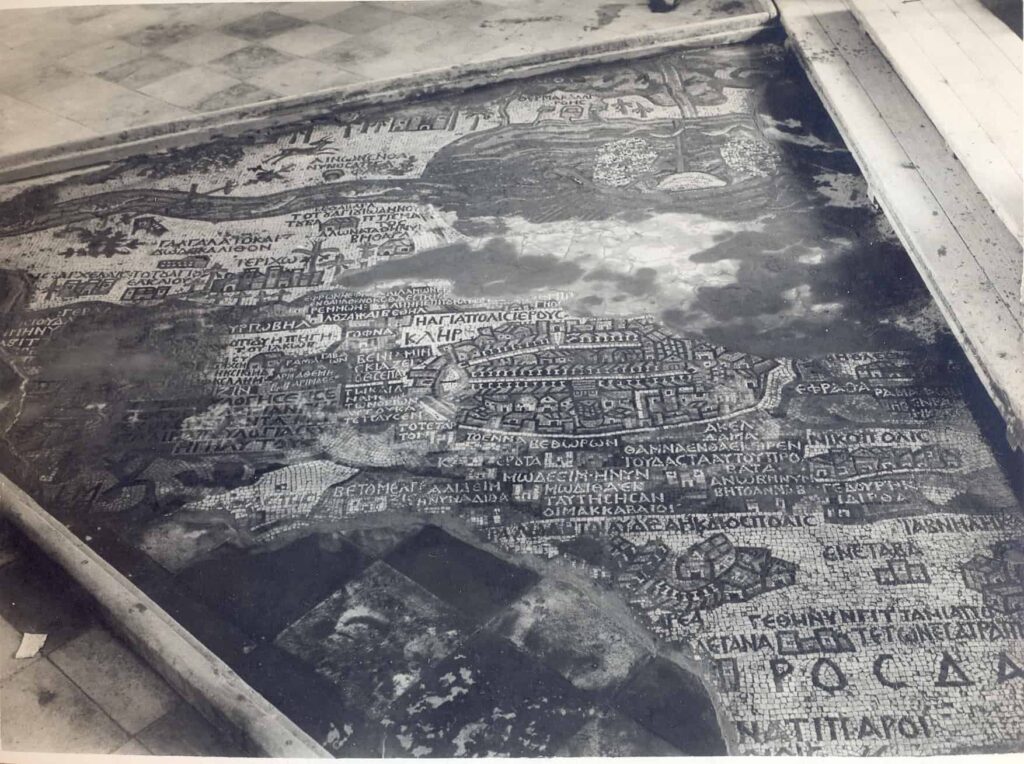

A faithful stone copy of the Madaba Map is housed in the casting collection of the University of Göttingen. This article presents the details of the Madaba mosaic based on photos of this copy.

Discovery and Publication

Orthodox Arab Christians from al-Karak left their hometown in the 1880s due to a local conflict. They petitioned the Ottoman government in Istanbul to settle on the large tell of the Byzantine city of Madaba. The Ottoman authorities stipulated that churches could only be built where churches had stood centuries ago. Consequently, the late antique and Byzantine city of Madaba was specifically searched for the foundations of churches.

In 1884, the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem, Nikodemos I, was informed about the discovery of the mosaic floor during the construction of the Church of St. George; reactions are not documented. In 1897, Cleopas M. Koikylides, the librarian of this patriarchate, saw the mosaic in the now completed church in Madaba and recognized its significance. His publication drew the attention of the academic world to the mosaic map. Koikylides published a schematic drawing of the mosaic map. Later visitors did the same. In 1901, the German Association for the Exploration of Palestine commissioned the Jerusalem architect Paul Palmer to make an accurate reproduction. Palmer completed the colored drawing in 1902, and the association’s chairman, Hermann Guthe, published it as a colored plate in 1906. This set a new standard of quality. Palmer’s drawing served as the basis for literature on the Madaba Map for decades. Even Michael Avi-Yonah relied on it for his 1954 publication on the Madaba Map.

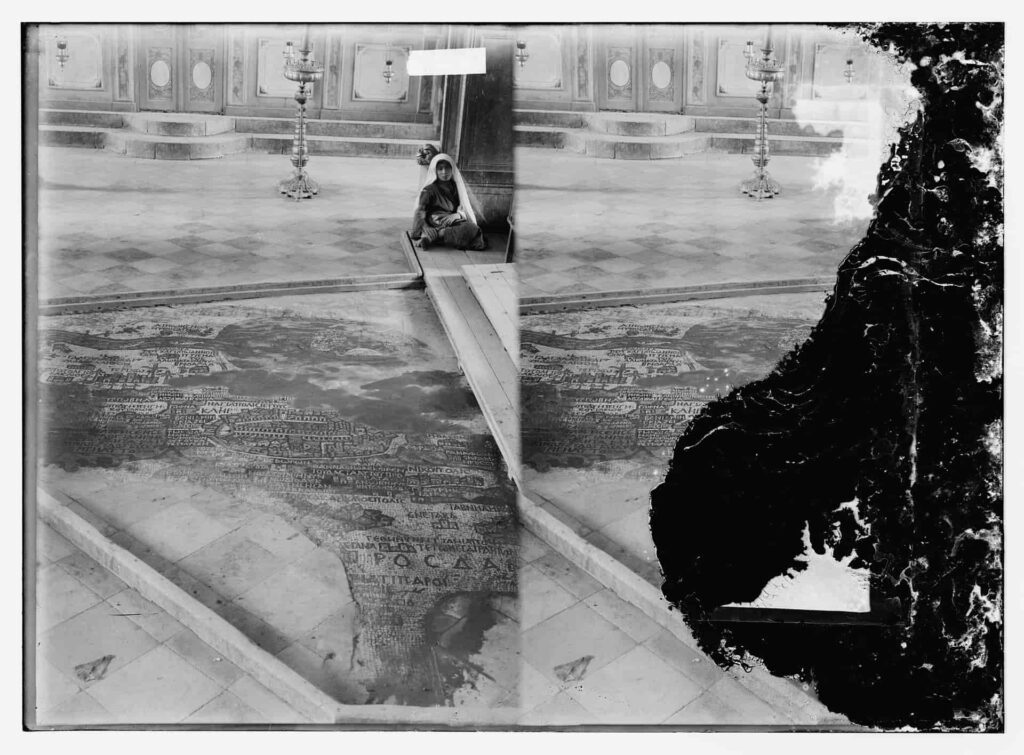

After the restoration of the Madaba Map in 1965, Herbert Donner and Heinz Cüppers published a volume in 1977 documenting the mosaic map with photos. This included the peripheral areas that were covered with cement during Palmer’s time and therefore were not drawn by him. There is no photographic panoramic view of the mosaic instead of Palmer’s drawing. Whichever angle one chooses, parts of the mosaic are always hidden by modern pillars.

Description

The Greek Orthodox Church of St. George in Madaba, completed in 1896, was built on the foundations of an early Byzantine predecessor church. The current spatial arrangement largely corresponds, except for the pillar placement, to the predecessor church, which was, however, larger. The mosaic was a rectangular picture field in front of the sanctuary. It originally measured about 24 m × 6 m and spanned the entire width of the church nave.

The Madaba Map originally depicted an area from Lebanon in the north to the Nile Delta in the south and from the Mediterranean in the west to the Arabian Desert in the east. The viewer looks eastward, from an imaginary location high above the Mediterranean, over Jerusalem and the Jordan, towards the east bank where Madaba is located. The mosaic map is not oriented to the north but to the east, aligning with the orientation of the church space.

The macro-topography, which is not easily discernible in the current fragmentary state, likely adhered to late antique table work conventions: mountain ranges depicted in brown hues, along with rivers, lakes, and coastlines (blue), structured the landscape. Numerous individual pieces of information were inserted into this basic structure. All natural geographic units are labeled in Greek script, mostly referring to the Old Testament.

In a combination of oblique perspective and bird’s-eye view, approximately 150 cities and villages are depicted and named on the mosaic map. The topography became quite busy due to this wealth of detail. A number of large city vignettes counteract this and facilitate orientation, especially in Jerusalem, but also in Neapolis, Pelusium, Charachmoba, Ashkelon, and Gaza, which are highlighted as centers of urban life. The tradition of city vignettes originates from late-antique city boards (compare the depiction in the Notitia dignitatum). With few exceptions, churches are marked with red roofs, palaces and residential buildings have yellowish-gray roofs, and squares are recognizable by their brown color.

A contiguous fragment of approximately 15.70 m × 5.60 m is preserved; this corresponds to about 25 percent of the original map. In addition, there are two fragments in the northern side aisle:

- Fragment A shows a location with a church, likely identifiable with ʿAkbara in Upper Galilee, attested to by the inscription ΑΓΒΑΡѠ[Ν] Agbarō[n].

- Fragment B, measuring approximately 1.25 m × 0.5 m, was first described by Eugène Germer-Durand in 1897. At his time, a part of the Mediterranean with a ship was still visible. In 1965, the fragment was smaller, showing only mountain ranges, two unidentifiable incomplete place names, and the blessing over the tribe of Zebulun (Gen 49:13 in the Septuagint version). While historically, this tribal territory is to be sought in Lower Galilee, the Byzantine mosaicist extended it to modern-day Lebanon.

The following division of the mosaic map into ten panels is based on the approach taken by Paul Palmer.

Top row:

- Panel I: Jordan

- Panel II: Confluence of the Jordan into the Dead Sea

- Panel III: Central Dead Sea and East Jordanian Highlands with Charachmoba (al-Karak)

- Panel IV: Southern end of the Dead Sea

- Panel V: (only parts of inscriptions)

Bottom row:

- Panel VI: Neapolis (Nablus) and surroundings

- Panel VII: Jerusalem and surroundings

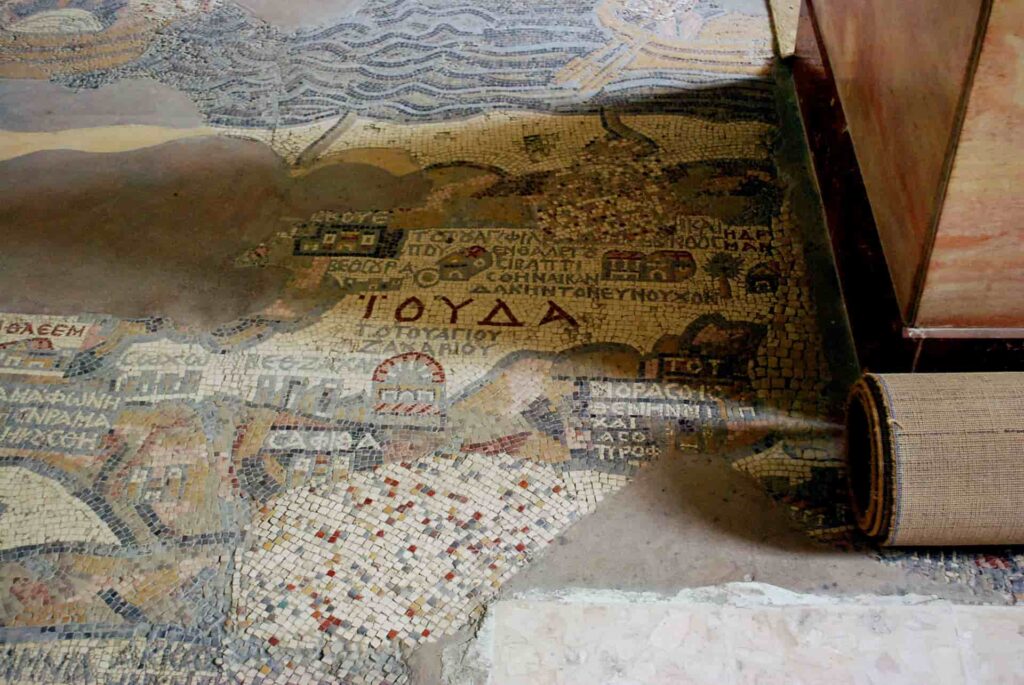

- Panel VIII: Judean Desert with Philippus, Zacharias, and Abraham sanctuaries; Ashkelon

- Panel IX: Gaza and surroundings

- Panel X: Lower Egypt

Jerusalem and Surroundings (Panel VII)

The largest and most detailed element of the topographic depiction is “the holy city of Jerusalem” (ancient Greek Η ΑΓΙΑ ΠΟΛΙϹ ΙΕΡΟΥϹΑ[ΛΗΜ] hē hagía pólis Ierousa[lḗm]) at the center of the map. The city vignette of Jerusalem lay on the axis of the church. The site of Madaba, not preserved on the fragment, lay on the extension of this axis and directly in front of the bema. Jerusalem, as the center of the world, is also the focal point of the Madaba Map. In Jerusalem, it was not the Church of the Holy Sepulchre but the base of the column at the Damascus Gate that was chosen as the central point of the map.

Walls and Gates

Jerusalem is depicted within its city walls as an oval. From a fictional location high in the west, the viewer looks “perspectivally” down on Jerusalem; he sees the western wall from the outside and the eastern wall from the inside. The late antique Byzantine city wall of Jerusalem is depicted. According to widespread dating, it was completed in the 440s under Empress Aelia Eudocia. In contrast to the present-day city wall of Jerusalem, built in 1517 under Sultan Suleiman I, the Byzantine city wall also enclosed the southwest hill (Mount Zion) and the southeast hill (with the Pool of Siloam at its foot). However, it is also held that Jerusalem remained an open city in late antiquity. In this case, the Jerusalem vignette provides a terminus ante quem for the construction of the Byzantine city wall, as this wall is depicted on the mosaic.

Within the city walls of Jerusalem, there are 19 towers and several city gates. According to ancient and medieval tradition, the northern city gate is particularly emphasized. The northern gate, today’s Damascus Gate, was called the Gate of Stephen in Byzantine times. On the city side of the gate square stood a column, probably dating from the time of Emperor Hadrian, which is now interpreted as the “symbol of the center of the world” and therefore forms the geographic reference point of the Madaba Map. Continuing clockwise from the Damascus Gate, two smaller gates can be seen in the city wall: the Lion’s Gate (in Byzantine times: Eastern Gate) and the Golden Gate. The southern part of the city wall is no longer included in the mosaic fragment. On the western side of Jerusalem, i.e., seen from the nave of the church, there is an inconspicuous gate that corresponds to the present-day Jaffa Gate and was called the Gate of David in Byzantine times.

Streets

The main streets of Byzantine Jerusalem are highlighted in white. The oval of the city is horizontally divided by the late antique Cardo Maximus (= Suq Chan ez-Zeit) with covered colonnades on both sides of the street. The stairs of the Constantinian Church of the Holy Sepulchre interrupt the colonnades on the west side.

From the column square at the Damascus Gate, the Cardo secundus (= Tariq al-Wad) branches off, running through the inner-city valley in the east of Jerusalem. It also has covered colonnades, but they are only depicted on the eastern (rear) side of the street. The street from the Cardo secundus to the Lion’s Gate is now known as the beginning of the Via Dolorosa, an inner-city pilgrimage route that did not exist in early Byzantine times.

The late antique Decumanus is depicted without colonnades. It starts from the Jaffa Gate and appears to end at the intersection with the Cardo Maximus on the Madaba Map, which does not correspond to reality and is probably due to the mosaicist’s lack of space.

Churches and Pilgrimage Sites

In the center of the city is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which is seen from the nave of the church upside down. This resulted from the mosaicist wanting to depict the Cardo Maximus in all its splendor, and therefore with colonnades on both sides. The main street was, so to speak, “unfolded,” and the western colonnades are upside down. The staircase leading to the propylaeum of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre interrupts the western colonnades; therefore, the church is also upside down.

The most significant church in Christendom is depicted in detail. It features the characteristic arrangement of surrounding and overarching rooms typical of Constantinian church architecture. From the Cardo, the visitor entered the basilica through the propylaeum and atrium, depicted on the map with a roof and gable, and reached the Holy Sepulchre shrine in the center of the Constantinian Anastasis rotunda, depicted on the map with a yellow (gilded) dome.

On the southern side of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was a subsidiary building, poorly known from sources, interpreted as a baptistery. On the mosaic map, it appears as a house with a flat roof, two doors, and a window. West of it is a diamond-shaped square, perhaps the forum of the late antique city. North of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, three residential buildings near the Cardo Maximus are tentatively identified as the palace of the Jerusalem Patriarch, the house of the clerics, and the guesthouse of the Patriarchate.

Of the numerous churches and pilgrimage sites in Jerusalem, only the major and securely identified ones are mentioned below. They are located in the southern part of the city:

- The large basilica in the southeast, adjacent to the Cardo Maximus with its gable wall, is the Nea Theotokos Church, built under Emperor Justinian. It is distinguished by a yellow (gilded) double portal.

- The slightly smaller church next to it on the right, with a yellow (gilded) gable, is the Pilgrimage Church, which commemorated the healing of the man born blind by Jesus. In the courtyard in front of its entrance, the Pool of Siloam is depicted as a black, white-framed square. Along the long side of this pilgrimage church, the Pool of Siloam is followed by an outdoor facility. Max Küchler characterizes the entire complex in the 6th century as a “religious-secular healing spa.”

- The dominant church in the southwest of Jerusalem is the Basilica on Mount Zion. It bore the honorary title “Mother of all Churches” and, after the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, had the second-highest rank. This was because the upper room was located here, where, according to the Acts of the Apostles, the Pentecost event took place. On the Madaba Map, this large church is depicted with a yellow (gilded) double portal and gable field; to the south, it is followed (with a red roof) by the diaconicon, whose connection to the current pilgrimage sites of David’s Tomb and the Cenacle is unclear.

The Temple Mount in the southeast is depicted as disproportionately smaller, reflecting its lesser importance in the Byzantine city. A rectangle divided into three stripes at the southern end of the Cardo secundus on the Madaba Map is suggested by Herbert Donner as the great staircase that led from the south to the esplanade of the Temple Mount. Michael Avi-Yonah, on the other hand, considers this structure to be “the earliest preserved representation of the Western or Wailing Wall.”

Before the Gates of Jerusalem

Above the Jerusalem vignette, the Christian pilgrimage site of Gethsemane (ΓΗΘϹ[ΙΜΑΝΗ] Gēths[imanē]) is depicted as a small church building.

To the left of the Jerusalem vignette, the blessing over the tribe of Benjamin in Deuteronomy 33:12 is written in the Septuagint version. The Septuagint translator had not realized that “shoulders” in the Hebrew text was a poetic term for mountain slopes; the Madaba Map corrected the Septuagint to read: “Benjamin, God protects him, and he dwells between his mountains.”

As the only overland road, the road leading from the Damascus Gate to Neapolis (Nablus) is marked by white tesserae. Another road is recognizable by its milestones: Below (that is, west of) Jerusalem, the “fourth milestone” (ΤΟ ΤΕΤΑΡΤΟΝ tó tétarton) and the “ninth milestone” (ΤΟ ΕΝΝΑ tó enná) are listed, two stations (mansiones, mutationes) on the road from Jerusalem to Nikopolis and Diospolis (Lydda). Further south, also on this road, is the location of Bethoron (ΒΕΘѠΡΟΝ) with the “Ascent of Bethoron” mentioned multiple times in the Bible; this is perhaps indicated by the black tesserae beneath the place name.

East of Bethoron is “Modeïm (ΜѠΔΕΕΙΜ), now Moditha (ΜѠΔΙΘΑ), from where the Maccabees originated.” The formulation almost completely matches that of Eusebius of Caesarea’s Onomasticon. Then follows “Thamna (ΘΑΜΝΑ), where Judah sheared his sheep” (Genesis 38:12-13), and Akeldama (ΑΚΕΛΔΑΜΑ), the cemetery land purchased with the thirty pieces of silver by Judas Iscariot (Matthew 27:6-8), which, according to the Onomasticon of Eusebius, is located near Mount Zion.

Neapolis (Nablus) and Surroundings (Panel VI)

Between Jerusalem and Neapolis, there is a text field with red letters on a brown background as a montage of two blessings over the tribe of Joseph in the wording of the Septuagint:

- Genesis 49:25 (Jacob’s blessing): “Joseph, God has blessed you with the blessing of the earth, with the choicest gifts of the ancient mountains.”

- Deuteronomy 33:13 (Moses’ blessing): “And of Joseph he said: Blessed of the Lord is his land, with the precious things of heaven.”

Neapolis (ΝΕΑΠΟΛΙϹ) was marked by a large city vignette. It is damaged and discolored black from a fire. A segment of the city wall with several towers is preserved. From the East Gate, a colonnaded street leads to the West Gate and crosses the north-south road. To the left of the intersection of these two main axes stands a small building with an entrance flanked by columns, possibly a thermal bath, located roughly where the an-Naṣr Mosque stands today. An conspicuous semi-circular structure at the southern edge of the city was perhaps a nymphaeum. This interpretation is supported by the findings of modern excavations at ʿAin Qaryun. A large basilica may be the main church of the city, which was damaged in 484 during an attack by Samaritans.

The mountains of Gerizim and Ebal are depicted twice on the Madaba Map due to conflicting Jewish and Samaritan traditions. Eusebius followed the Jewish tradition in his Onomasticon and localized the two mountains east of Nablus, in the mountainous region northwest of Jericho. In the Madaba Map, they are entered as “Garizeim” (ΓΑΡΙΖΕΙΜ) and “Gebal” (ΓΕΒΑΛ). The mosaicist also considered the Samaritan local tradition: To the right of the city vignette of Neapolis is the “Mount Gobel” (ΤΟΥΡ ΓѠΒΗΛ tour Gōbēl) with Jacob’s Well at its foot, and the “Mount Garizin” (ΤΟΥΡ ΓΑΡΙΖΙΝ tour Garizin) a bit further west.

Jericho and the Jordan Valley (Panels I, II, VI)

A particularly well-preserved segment of the Madaba Map shows the lower Jordan Valley with the large oasis of Jericho (ΙΕΡΙΧϹ Ierichō) and several Christian pilgrimage sites. The depiction is interspersed with depictions of animals and plants. For example, on the eastern bank, there is a Nubian ibex being chased by a (made unrecognizable by iconoclasts) big cat, probably a leopard. Fish are swimming in the Jordan, one of which is swimming against the current to avoid entering the Dead Sea, where no fish can live due to the salt content.

Around Jericho, and occasionally at other locations, several date palms are depicted. On both sides of the Jordan, the mosaicist has depicted shrubs that, due to their egg-shaped leaflets, are tentatively identified as balsam (Commiphora gileadensis). Since ancient times, the production of dates and balsam has been the source of wealth in this region; balsam cultivation ended due to the decline of plantation agriculture in early Islamic times.

Jericho is not distinguished by a city vignette but is stylized as a medium-sized city with walls, five towers, and two gates; the roofs of three churches in the city center cannot be assigned to specific church buildings.

North of Jericho is a sanctuary of the Old Testament prophet Elisha (ΤΟ ΤΟΥ ΑΓΙΟΥ ΕΛΙϹΑΙΟΥ to tou hagiou Elisaiou). The Elisha Memorial Church is depicted as a dome-shaped building flanked by two towers.

In the northeast of Jericho, a biblical site is listed, which Eusebius’ Onomasticon designates as a pilgrimage site: “Gilgal (ΓΑΛΓΑΛΑ Galgala), also called Twelve Stones.” As known from the Onomasticon and pilgrimage reports, the twelve stones shown there were the ones set up by the Israelites according to the biblical account (Joshua 4:20) after crossing the Jordan; they are also included on the Madaba Map “in the form of a two-layered wall” in front of the basilica.

For easier crossing of the Jordan, a ferry service was established in the 6th century. On the Madaba Map, posts are driven into both banks and the middle of the river, connected by a rope. The small oarless boat is pulled across the Jordan by the ferryman on the rope. On the west bank, a military post on a watchtower with a ladder controls the ferry traffic.

At the confluence of the Jordan into the Dead Sea, since the beginning of pilgrimages in the 4th century, the site of the baptism of Jesus was located. Here, a baptism site on the east bank competed with one more conveniently accessible from Jerusalem and Bethlehem on the west bank. The Madaba Map shows that by the 6th century, the west bank tradition had largely prevailed. There, a church with red lettering is highlighted: “Bethabara (ΒΕΘΑΒΑΡΑ Bethabara), the (church) of the baptism of Saint John”. On the east bank, the mosaic indicates a cave or spring and the place Ainon (ΑΙΝѠΝ Ainōn) with the explanation “now there is the sycamore tree (Ο ϹΑΠϹΑΦΑϹ ho sapsaphãs).” This is an allusion to the Sapsas Monastery in the Wadi el-Ḥarrar, which preserved the memory of John the Baptist and the prophet Elijah. Monastic complexes are not depicted on the mosaic map.

Dead Sea (Panels II, III, IV)

On the preserved fragment of the Madaba Map, the Dead Sea vies with Jerusalem for prominence due to its size and central location. Its significance arises from the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, which were localized here, and its proximity to the baptism site of Jesus. Its label is found on the eastern shore between the two “foot-like” gaps; it is entirely taken from Eusebius’ Onomasticon and reads: “Salt or Asphalt Sea, also Dead Sea.”

The Lisan Peninsula is not depicted on the Madaba Map, which is usually explained as an inaccuracy of the mosaicist. However, it is also possible that the shallow southern part of the Dead Sea dried up during a pronounced dry period in the 560s and the Lisan Peninsula became the southern shore of the inland sea.

The Madaba Map attests to shipping on the Dead Sea, which was also known from antiquity. Two boats equipped with oars and sails are depicted. The two crew members of each boat have been made unrecognizable by iconoclasts. Below the mast, the cargo being transported is visible; it is interpreted as salt or grain. However, in one of the boats, the sail is wrapped around the yardarm. This is an absurd depiction, as the sail would have become non-functional. The mosaicist’s ignorance is remarkable because boat depictions were part of the common visual repertoire. How the boat representation could have appeared without damage from the iconoclasts is shown by the mosaic from Haditha, which is approximately contemporary.

Charachmoba (al-Karak) and the Eastern Jordan Land (Panel III)

The Madaba Map (photo) shows on the eastern shore of the Dead Sea the “hot springs of Callirhoe (ΘΕΡΜΑ ΚΑΛΛΙΡΟΕϹ therma Kallirhoes),” a bathing resort known to Flavius Josephus. By the 6th century, there was certainly no longer any luxury from the Hellenistic and early Roman periods. The mosaicist depicted architecturally framed springs and streams under palm trees. Since archaeological findings do not confirm this facility, it is also possible that it is not an early Byzantine bathing resort but only a reminiscence of the once-famous hot springs.

At the southern end of the Dead Sea, the medium-sized city of Zoora (ΖΟΟΡΑ), a Byzantine administrative center and bishopric, is visible. In the mountainous region behind it, the Madaba Map records a memorial church of Saint Lot (ΤΟ ΤΟΥ ΑΓΙΟΥ ΛѠΤ to tou hagiou Lōt), which is not mentioned in other sources.

At the top of the preserved map fragment is the city vignette of Charachmoba ([ΧΑΡ]ΑΧΜѠΒ[Α] [Char]achmōb[a]), “Palisade of Moab.” This is the Byzantine name for al-Karak. The Madaba Map is the only source for the Byzantine city, which was also a bishopric. The mosaicist had local knowledge. He depicted Charachmoba as a heavily fortified city with walls and towers. In the south, there is a city gate flanked by two towers, and to the east of it, there is a church recognizable by its red roof. Two colonnaded main streets running north–south are visible. One of them leads to a large church, probably the cathedral.

Below, to the west of al-Karak, the Madaba Map shows a triple-dome structure with the inscription “Cult House, or also Maioumas (ΒΕΤΟΜΑΡϹΕΑ Η Κ(ΑΙ) ΜΑΙΟΥΜΑϹ Betomarsea hē k(aì) Maioumas).” The inclusion of such a pagan establishment, which could only have a niche existence in the Byzantine Empire, on the Madaba Map is subject to controversy.

Bethlehem and the Judean Highlands (Panels VII and VIII)

Next to Jerusalem, Bethlehem (ΒΗΘΛΕΕΜ Bēthleem) was the second most important Christian pilgrimage site, conveniently accessible from Jerusalem. Reflecting its importance, the place name appears in red. However, the depiction of the Nativity Church is not particularly prominent. After the Constantinian basilica possibly burned down following the earthquake of 510, the present-day representative church was built during the reign of Justinian. Perhaps the Madaba Map depicts the state before the completion of the Justinianic construction.

South of Bethlehem lies the place Socho (ϹѠΧѠ Sōchō), followed by Bethzachar (ΒΕΘΖΑΧΑΡ) with the striking memorial church of Saint Zacharias: “A red-covered narthex or portico is attached to a basilica with three windows or gates in the front, and to this, a semicircular courtyard surrounded by a colonnaded hall,” the actual memorial building. Various biblical traditions about Zacharias have merged in the saint venerated here: the author of the Book of Zechariah, the high priest Zechariah killed by King Joash (2 Chronicles 24:20-22), and Zacharias, the father of John the Baptist.

Above the Zacharias sanctuary, the large inscription ΙΟΥΔΑ marks the region as the territory of the tribe of Judah. A little further east, one of the few New Testament memorial sites is entered on the Madaba Map. Symbols for a basilica and a well are visible with the explanation: “the (place) of Saint Philip, where, as they say, the eunuch of Candace was baptized.” As in other Byzantine sources, the high court official of Queen Candace, whom Philip baptized (Acts 8:26-40), became a eunuch named Candaces. The mosaic map is the only source for this basilica. In 1918, Andreas Evaristus Mader described the ruin of a mosque built on Byzantine foundations at ʿēn eḏ-ḏirwe, which he identified with the Philippus Church of the Madaba Map.

South of the Philippus sanctuary, the Madaba Map records an Abraham’s Church and next to it the sacred grove of Mamre; this tree is referred to in the caption as both a terebinth and an oak. In Late Antiquity, Mamre (Ramet el-Chalil) was a holy site visited by Jews, Christians, and pagans. Emperor Constantine claimed Mamre exclusively for Christian worship with his (rather modest in size) church building, which can be seen on the map. Nevertheless, the multi-religious practice there continued unabated.

The building to the right of the Mamre sacred grove already belongs to the city of Hebron, whose name as well as other structures on the mosaic map have not been preserved.

Cities on the Mediterranean Coast (Panels VIII and IX)

The lower border of the mosaic map is the Mediterranean Sea; however, it is only recognizable in small fragments. From north to south, the following coastal cities are visible on the map: the port of Ashdod, Ashkelon, and Gaza.

The fragment of the port of Ashdod (“Ashdod by the Sea, ΑΖѠΤΟϹ ΠΑΡΑΛΟ[Ϲ] Azōtos paralo[s]”) on the Madaba Map does not reveal the significant harbor facility and only allows the observation that there were several churches here.

Ashkelon

The city vignette of Ashkelon (ΑϹΚΑΛѠ[Ν] Askalō[n]), on the other hand, stands out for its richness of detail. The city was walled; the eastern gate is two stories high and flanked by towers. In front of it is a city-side square from which two colonnaded streets extend as the east-west axes of the city. Where the left of these two main streets intersects with the similarly colonnaded north-south street, there is an arched structure laid with yellowish tesserae, which is more aptly referred to as a tetrapylon than a triumphal arch. The structures in the angle between the major east-west streets are not clearly identifiable; Donner suggests that they could be fountain installations for which Byzantine Ashkelon was famous. There is a continuity in the city layout of Ashkelon from Late Antiquity to the Crusader-period city, in which the prominent eastern gate bore the name Jerusalem Gate.

Gaza

Gaza ([Γ]ΑΖΑ [G]aza) was a bishopric and a significant urban center in Byzantine times. “The mosaicist has taken into account the city’s reputation on our map and accordingly indicated the architectural splendor of the city in its vignette.” Only the southern half of the city vignette is preserved; its interpretation is complicated by the fact that the Byzantine city of Gaza has been modernized and there are hardly any archaeological investigations. Like Jerusalem, Gaza is depicted as a walled oval. The colonnaded Cardo runs east-west and corresponds approximately to the modern as-Suq al-kabīr street. At the intersection of the Cardo and Decumanus is a large open square in the city center, which is presumed to be in the area of modern Ḫān az-Zēt.

In the southwestern part of Gaza, the mosaicist depicted two large churches. The rhetorician Chorikios of Gaza wrote detailed descriptions in the 6th century of the Church of St. Sergius and the Church of St. Stephen in his hometown. However, since the city vignette is only partially preserved, the identification of the two church buildings as the Sergius and Stephen churches remains uncertain.

In the southeastern area of the city, a theater stands out. Zeev Weiss suggests construction in the Roman imperial period, while it was later incorporated into the city wall. He interprets the yellowish semicircle in the middle as the orchestra, the white and pale red semicircles surrounding it as the divided cavea, and the dark red stripes dividing the outer cavea into segments as stairs (scalariae).

Surroundings of Gaza

Northwest of Gaza is the city’s port with the partially preserved inscription “Maioumas, also Neapolis (called)” ([ΜΑΙΟΥΜΑϹ Η] ΚΑΙ ΝΕΑ[ΠΟ]ΛΙϹ [Maioumas he] kaì Neápolis). Southwest of Gaza, the mosaicist depicted a Church of Saint Victor (<Τ>Ο ΤΟΥ ΑΓΙΟΥ ΒΙΚΤΟΡΟϹ ò toũ hagíou Viktoros) with a red-roofed portico. According to the Pilgrim of Piacenza, the tomb of Saint Victor was located within Maioumas and not, as on the Madaba Map, between Maioumas and Gaza. South of Gaza, a group of villages is recorded, some of whose names are only attested by the Madaba Map. Here, the mosaicist likely had personal knowledge of the locations.

All stations of the coastal road connecting Palestine with Egypt are recorded on the Madaba Map from Gaza: Thauatha, Raphia, Betylion, “the border between Egypt and Palestine,” Rhinokorura, Ostrakine, Kasin, Pentaschoinon, Aphnaion, and Pelusium. From Betylion onwards, one station follows another along the Mediterranean coast.

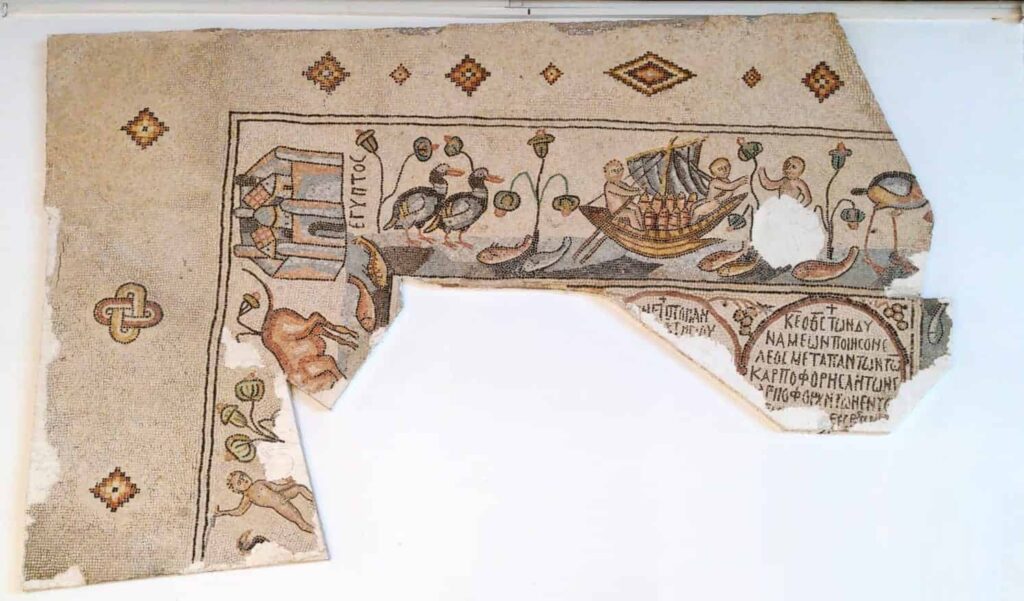

Lower Egypt (Panel X)

Pelusium (ΤΟ ΠΗΛΟΥϹΙΝ Tò Pēlousin) is designated with a city vignette according to its importance as the “Gateway of Egypt.” Within the city walls, three colonnaded streets running east-west and three churches are visible. Among the other buildings, one has a yellow (= gilded) gable. The depiction of Pelusium cannot be related to the sparse archaeological findings and “remains a mystery.”

The representation of Lower Egypt differs from the rest of the Madaba Map. The places in the Nile Delta do not receive biblical references, although these could easily have been added using the source commonly used elsewhere, Eusebius’ Onomastikon. While the mosaicist otherwise made only isolated geographical and topographical errors, they are found here in abundance. One major error stands out: While the real coastline south of Gaza turns westward, on the mosaic map, it turns eastward, and therefore, the Nile does not flow from south to north but from east to west. This may have practical reasons: The elongated rectangular shape of the map should not be departed from. A theological reason is also possible: The Nile is one of the four rivers of paradise; paradise was presumed to be in the east; therefore, the Nile had to have its source in the east as well. Herbert Donner suggests that the mosaicist did not use Eusebius’ Onomastikon for the representation of the Nile Delta nor did they use a late Roman-Byzantine road map. Instead, they apparently relied on Herodotus’ description of the Delta region and combined it with a contemporary itinerary similar to the Itinerarium Antonini. Without personal knowledge of the locations, they created a map of Lower Egypt based on this, which, despite numerous errors, exceeded the accuracy of later maps until the beginning of modern cartography.

According to Donner, the Madaba mosaic is an accurate rendition of the description that Herodotus (Histories 17.2.3–6) gives of the Nile Delta’s distributaries. According to him, the Nile divides into three main branches in the Delta region: the Pelusiac, the Canopic, and in between, the Sebennytic branch. From the latter, two secondary branches diverge: the Saitic and the Mendesian branches. Additionally, Herodotus mentions two canals: the Bolbitine and the Bucolic canal. The Mendesian branch is missing on the preserved fragment of the Madaba Map. The two canals were treated by the mosaicist as branches of the Nile, and instead of Bolbitine, they wrote Bulbytine. Like the Jordan, the Nile is teeming with fish. A ship sails on the middle Nile branch. During restoration work in 1965, a crocodile laid with dark green glass tesserae was uncovered in the Nile at the upper edge of the map fragment.

Creation of the Mosaic

The city vignette of Jerusalem shows the Nea Theotokos Church, consecrated on November 20, 542. This provides a terminus post quem for the mosaic map. The absence of certain structures known from pilgrim reports of the 7th century could have various reasons, such as a lack of space. Therefore, Herbert Donner does not commit to the latest possible date. Michael Avi-Yonah suggests a creation date between the consecration of the Nea Theotokos Church and the death of Justinian in 565.

The patron of the Madaba mosaic is unknown, probably a learned monk or bishop. Peter Thomsen speculated in 1929 that the mosaicist was a certain Salamanios, who was named on a mosaic of the Apostles’ Church of Madaba along with the three donors. The fact that he was able to mention his name here shows that he was a famous artist. However, this theory did not find agreement. Martin Noth deemed it pointless to attribute further mosaics to Salamanios. There were apparently other mosaicists in Madaba and its surroundings.

Herbert Donner estimates that three workers, under the direction of the mosaicist, would have taken about half a year to create the mosaic. Over a million tesserae made of stone and glass were laid in a bed of solid lime mortar. The tesserae, available in a wide range of colors, were not cubic but rod-shaped; with a maximum surface area of two square centimeters, they were about 6 centimeters long. Smaller tesserae were used for humans, animals, plants, and intra-urban buildings. It is assumed that the lead mosaicist incised a preliminary drawing, and then structural lines were laid first, such as the Mediterranean coast, the shores of the Dead Sea, the Jordan River, the Nile with its branches, and the mountain ranges. Then the city vignettes and the longer inscriptions were laid, followed by the small towns with their inscriptions.

Sources of the Mosaicist

Among the written sources of the mosaicist, the Greek Bible takes first place. Old Testament quotations therefore follow the Septuagint. In addition, the Onomastikon of biblical place names by Eusebius of Caesarea was extensively used: of a total of 149 inscriptions on the preserved mosaic fragment, 61 inscriptions quote Eusebius more or less verbatim. Other literary sources, such as the works of Flavius Josephus or the Church Fathers, are not securely traceable. Contemporary maps and itineraries were certainly used. Finally, the mosaicist could draw on their own local knowledge to some extent. Yoram Tsafrir assumes that Byzantine pilgrimage literature was also equipped with parchment maps, which depicted the most important places in Palestine, the pilgrimage sites, and the connecting routes: “Such a map could well have been the primary source for the mosaicists and provided them with the majority of the information,” as some places were apparently only recorded because they were located on an important overland route.

Interpretations of the Mosaic

When the mosaic was completed, no pillars obstructed the viewer; it was visible from all sides. Herbert Donner assumes that there was a certain benefit for the residents of Madaba and its surroundings in that they could inform themselves in advance about pilgrimage destinations in the Holy Land that they might want to visit. However, the main purpose of the mosaic was to depict the Christian concept of salvation history in the form of a map. With Jerusalem as the center, numerous locations from the Old and New Testaments are represented. This corresponds to the liturgy, which is full of biblical references and also addresses salvation history in other ways. Worshipers could walk barefoot on the mosaic and thus move through the Holy Land.

Rainer Warland sees the Madaba mosaic map as a “testimony of a pilgrimage topography,” but one that is embedded in a broader overall concept. The centrally positioned blessing of Joseph points to the abundant fertility of the earth, a theme that can be found alongside river landscapes in other Byzantine churches (for example, in Tabgha). Because the flooding of the Nile was for antiquity the “embodiment of the life-giving principle.” Warland also ultimately sees liturgy as the frame of reference for such earthly images depicted on mosaic floors in churches.

Francesco Prontera, who treats the Madaba map in the context of ancient cartography, sees the captions to the place names, the numerous biblical quotations, and the special status of Jerusalem as indications of a “didactic objective of this chorography in the Ptolemaic sense of the word.”

It can be excluded that the Madaba map was intended to prepare long-distance pilgrims for visiting the Holy Land. Because if at all, they only came to the Transjordan at the end of their journey through Palestine. After the site of Jesus’ baptism had been moved from the east to the west bank of the Jordan, there was one less reason for them to cross the Jordan at all.

Damages and Conservation Measures

The preserved fragment of the mosaic map shows traces of damage and repair work. At an unknown time, the representations of people and animals as well as some inscriptions were made unrecognizable, but the areas were patched with the original tesserae. This may be related to the Iconoclasm during the reign of Yazid II (720–724), assuming that the church was used by the Christian community until the early Islamic period. Later, possibly in the context of the abandonment of Madaba in the mid-8th century, the church burned down, and the wooden roof collapsed. The tesserae of the mosaic map are therefore particularly discolored black in the area of Neapolis. Large gaps in the area of the Dead Sea and the loss of marginal areas may also be consequences of this church fire.

In the following centuries, the mosaic map suffered further losses. When graves, presumably children’s burials, were dug, the mosaic and its substrate were pierced. This created the “foot-like” gaps in the representation of the Dead Sea. Moles also caused damage. In an effort to secure the mosaic, the edges of the fragment were enclosed in dark cement during church construction work in the 1880s, and three larger gaps were filled with the same cement. In some cases, the cement covered several centimeters of the mosaic.

The fact that Madaba became a tourist destination led to additional damage to the mosaic map over the course of the 20th century. The floor mosaic had been covered with heavy wooden planks for protection, which rested on a wooden frame. For the tourists, these planks were then uncovered and re-laid each time. Over the years, the planks struck directly at the mosaic with their weight and destroyed many tesserae. For the sake of the tourists, the mosaic was sprinkled with water because it made the colors appear more vivid. Cooling and evaporation put the mosaic under tension, and because lateral expansion was not possible due to the enclosure with cement, the mosaic rippled, detached from the substrate, and threatened to crack.

In December 1964, the Volkswagen Foundation, at the initiative of the German Society for the Exploration of Palestine, finally provided 90,000 DM for the rescue of the mosaic. Under the direction of Heinz Cüppers, later director of the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier, and the Old Testament scholar Herbert Donner, urgently needed work to restore and conserve the remaining parts of the mosaic map was carried out from September 1965 to November 1965. The restorers removed the cement from the edges and gaps. It turned out that in the gap to the right above the city vignette of Jerusalem, the fine lime slurry in which the tesserae were embedded had been preserved; a negative impression of the lost tesserae could be taken with rubber.

Scientific Significance

The Madaba mosaic map is the oldest known geographical floor mosaic to date. It shows which Christian pilgrimage sites had been established in Palestine in the 6th century, thereby supplementing contemporary pilgrimage reports. Eusebius of Caesarea’s Onomasticon, which locates numerous biblical places, was known to the mosaicist; developments can be observed compared to this source from the 4th century. For example, the Madaba map shows that in the 6th century, the tradition of the site of Jesus’ baptism had shifted from the east to the west bank of the Jordan.

Time and again, the Madaba map proves useful in identifying late antique and early Byzantine buildings and roads. For example, in 1967, excavations in the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem uncovered the remains of a monumental basilica that could be identified as the Nea-Theotokos Church with the help of the Madaba map. However, the example of Kallirhoë on the east bank of the Dead Sea shows that the representation on the Madaba map does not always harmonize with the archaeological evidence.

Göttingen Copy of the Madaba Map

A true-to-life copy of the Madaba mosaic map has been on permanent loan from the Seminar for Christian Archaeology and Byzantine Art History since 1977 in the casting collection of the Archaeological Institute of the University of Göttingen. This cast made of colored polyester resin was made by the restorers of the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier during the restoration work in Madaba in 1965. “The Göttingen cast is the only copy of the mosaic worldwide. … Due to the vertical installation, the mosaic in Göttingen can be viewed more comfortably than in Madaba itself, where it still adorns the floor of the church.”

References

- Donner, 1992, p.11

- Donner, Herbert (1992). The Mosaic Map of Madaba: An Introductory Guide. Kampen: Pharos. p. 12. ISBN 9789039000113. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- Ute Friederich: Antike Kartographie

- Kallai-Kleinmann, Z. (1958). “The Town Lists of Judah, Simeon, Benjamin and Dan”. Vetus Testamentum. Leiden: Brill. 8 (2): 155. doi:10.2307/1516086. JSTOR 1516086.

- Dalman, Gustaf (2013). Work and Customs in Palestine. Vol. I/1. Translated by Nadia Abdulhadi Sukhtian. Ramallah: Dar Al Nasher. p. 65 (note 4). ISBN 9789950385-00-9. OCLC 1040774903.

- “Dig uncovers ancient Jerusalem street depicted on Byzantine map”.