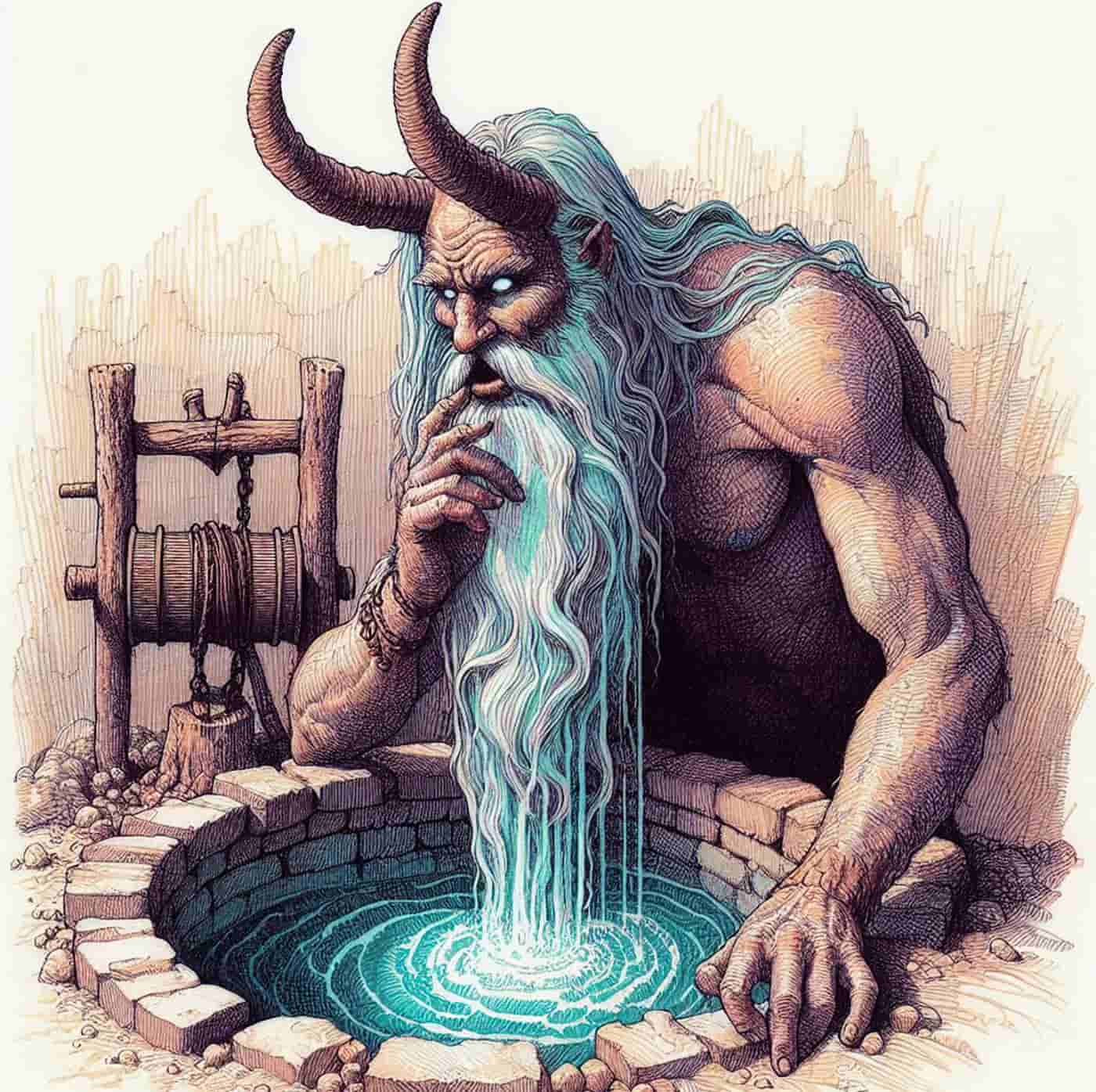

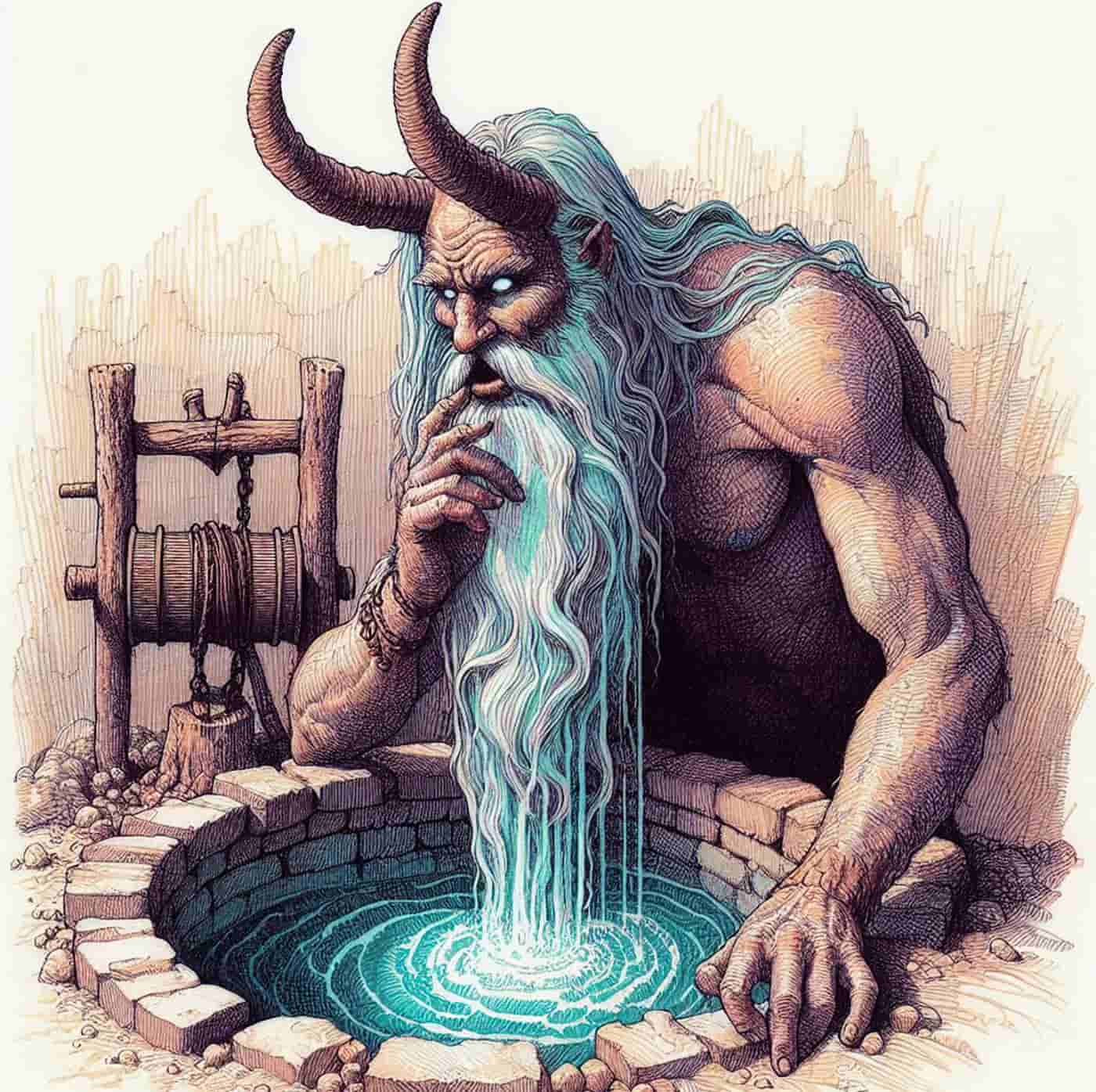

Mimir: A Saga of Norse Wisdom

After the Aesir delivered Mimir as a captive to the Vanir, the competing gods, the latter beheaded him and gave his head back to the former.

After the Aesir delivered Mimir as a captive to the Vanir, the competing gods, the latter beheaded him and gave his head back to the former.