- Romans Wore Togas

- The Roman Empire Had Many Slaves, and They Lived Very Poorly

- Emperor Caligula Made His Horse a Consul

- The Death of Gladiators in the Arena – A Favorite Spectacle of the Romans

- Nero Set Fire to Rome

- The Inhabitants of Ancient Rome Were Engulfed in Orgies and Feasts

- The Roman Empire Was the Largest in History

- Roman Legionnaires Wore Red Clothing and Armor

Romans Wore Togas

The traditional image of a Roman is that of a person wrapped in a white toga, proudly gazing at us from textbook illustrations or movie screens. However, as British archaeologist Alexandra Croom writes in her book Roman Clothing and Fashion, the toga was the primary garment of “a small number of people for a short period of time within a limited area of the empire.”

In fact, only Roman citizens had the right to wear wool togas. A Roman sent into exile lost this right, and foreigners were prohibited from wearing togas altogether.

To properly wear and maintain a toga, one needed a trained slave (or even several slaves). Therefore, only wealthy citizens could afford to wear togas daily. By the time of the late Republic and early Empire, as we learn from the writings of Martial (40–104 AD), togas were worn only on holidays and official occasions.

In everyday life, Romans preferred simple and comfortable clothing, such as the tunic — a shirt-like garment resembling a sack with holes for the head, arms, and torso, typically reaching the thighs (the toga was usually worn over it), as well as a cloak or mantle. Women wore the stola, a type of tunic that was wider, longer, pleated, and belted.

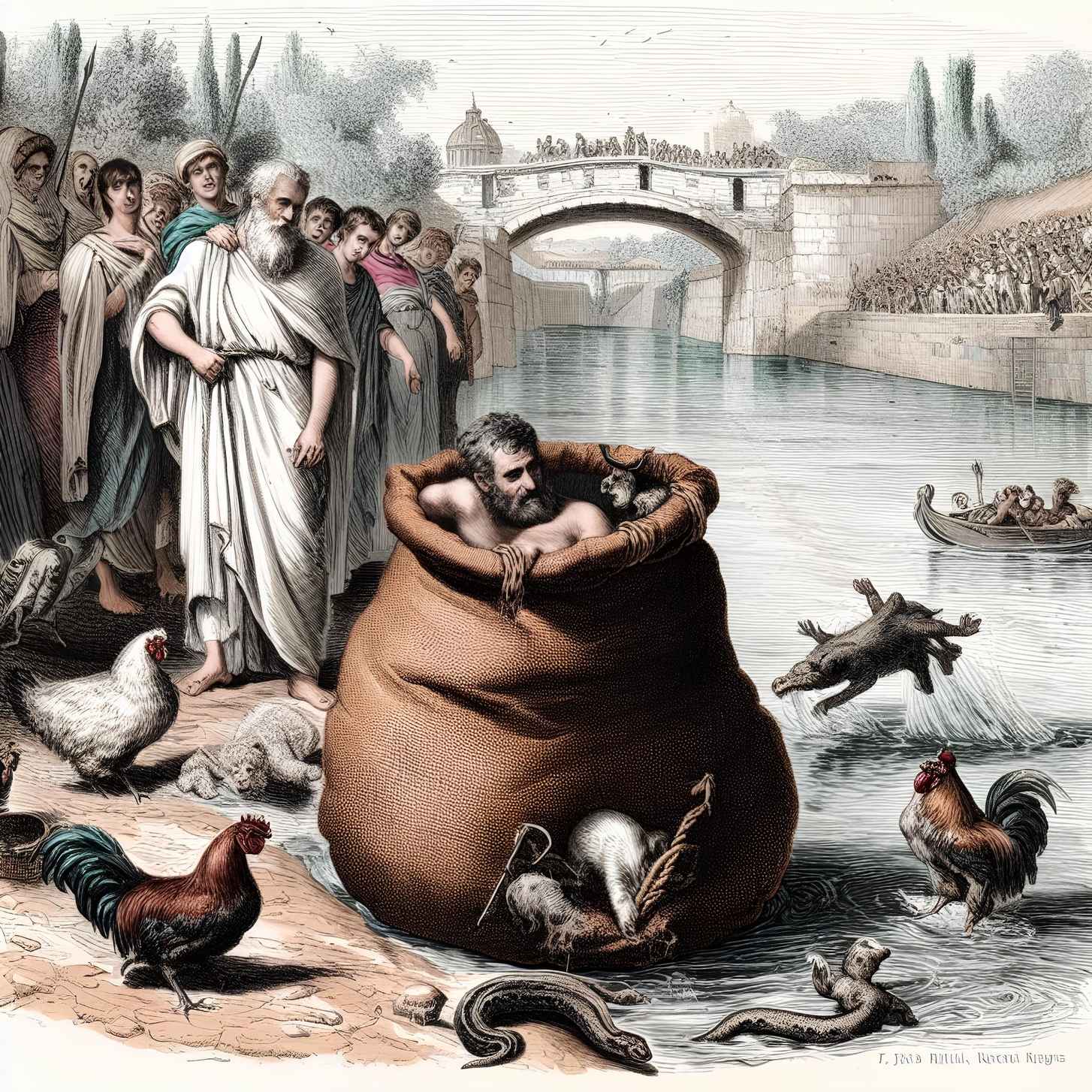

The Roman Empire Had Many Slaves, and They Lived Very Poorly

When people think of Roman slaves, they often imagine shackled individuals chained to the oars of Roman warships. However, only free men could serve in the Roman army and navy. Even slaves taken into the navy were granted freedom.

Slaves did not only perform heavy and dirty work: they were artisans, farmers, accountants, doctors, household servants, and teachers. Moreover, slaves could serve not only individual Roman citizens but also the state itself.

According to Roman beliefs, a slave had no personal identity, name, or ancestors, and thus no civil status. A slave could be sold (including to gladiatorial arenas and brothels), chained, and tortured. However, externally, slaves were indistinguishable from ordinary citizens. They dressed the same way, and the collars with the names of their masters, initially introduced for them, were quickly abolished. A slave could be freed and even obtain Roman citizenship. He could own property given to him by his master and conduct business.

Of course, this was not an enviable position, but it also didn’t resemble the fate of slaves depicted in films.

Moreover, as the empire expanded, efforts were made to legally combat cruelty toward slaves. Emperor Claudius freed slaves whose masters neglected them during illness. Later, it was forbidden to throw slaves to wild animals in gladiatorial arenas. Emperor Hadrian prohibited the arbitrary killing of slaves, their imprisonment, and their sale into prostitution and gladiatorial fights.

Despite several uprisings (the peak of which occurred during the height of slavery in the 2nd–1st centuries BC), slaves did not play a major role in Rome’s social conflicts. Free workers also fought in Spartacus’ army. Even in the 2nd–1st centuries BC, when slavery was most widespread, slaves made up only 35–40% of the population in Roman Italy. Throughout the empire, which stretched from the British Isles to Egypt, out of its 50–60 million inhabitants, only about five million (8–10%) were slaves.

Emperor Caligula Made His Horse a Consul

This famous story is often cited as an example of the decadence and excess of Roman rulers: Emperor Caligula supposedly made his horse Incitatus a senator. However, in reality, this never happened.

The myth originates from Roman History by Dio Cassius, who lived a century and a half after Caligula’s reign and was not particularly fond of him. But Cassius only mentions the emperor’s intention, not an actual event:

One of his horses, whom he called Incitatus, Gaius invited to dinner, during which he offered him golden barley and drank to his health from golden cups. He also swore by the life and fate of this horse and even promised to make him consul. And he undoubtedly would have done so had he lived longer.

Dio Cassius, Roman History, Book LIX.

Additionally, Gaius himself was a member of the college of priests of his own cult and appointed his horse as one of his companions; birds of exquisite and expensive breeds were sacrificed to him daily.

However, modern research even questions Caligula’s intention to make his horse a senator. In 2014, English researcher Frank Woods analyzed this story in an article published in an Oxford University journal. He concluded that Caligula’s joke, based on a play on words, was taken out of context. Another viewpoint suggests that Caligula used such antics to mock the senators’ greed and intimidate them.

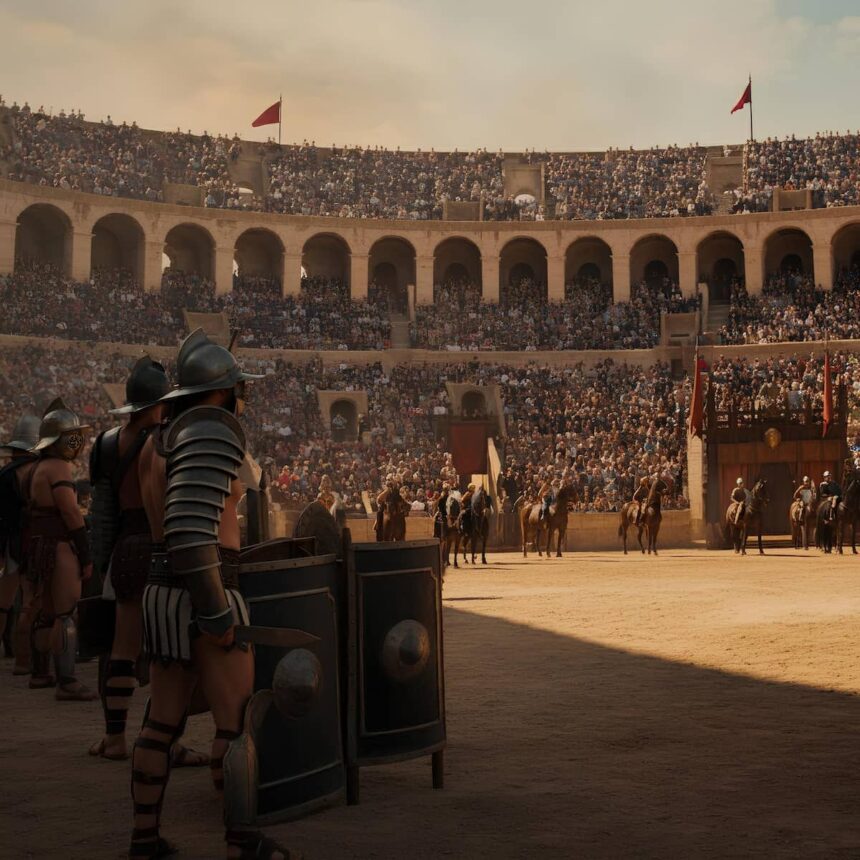

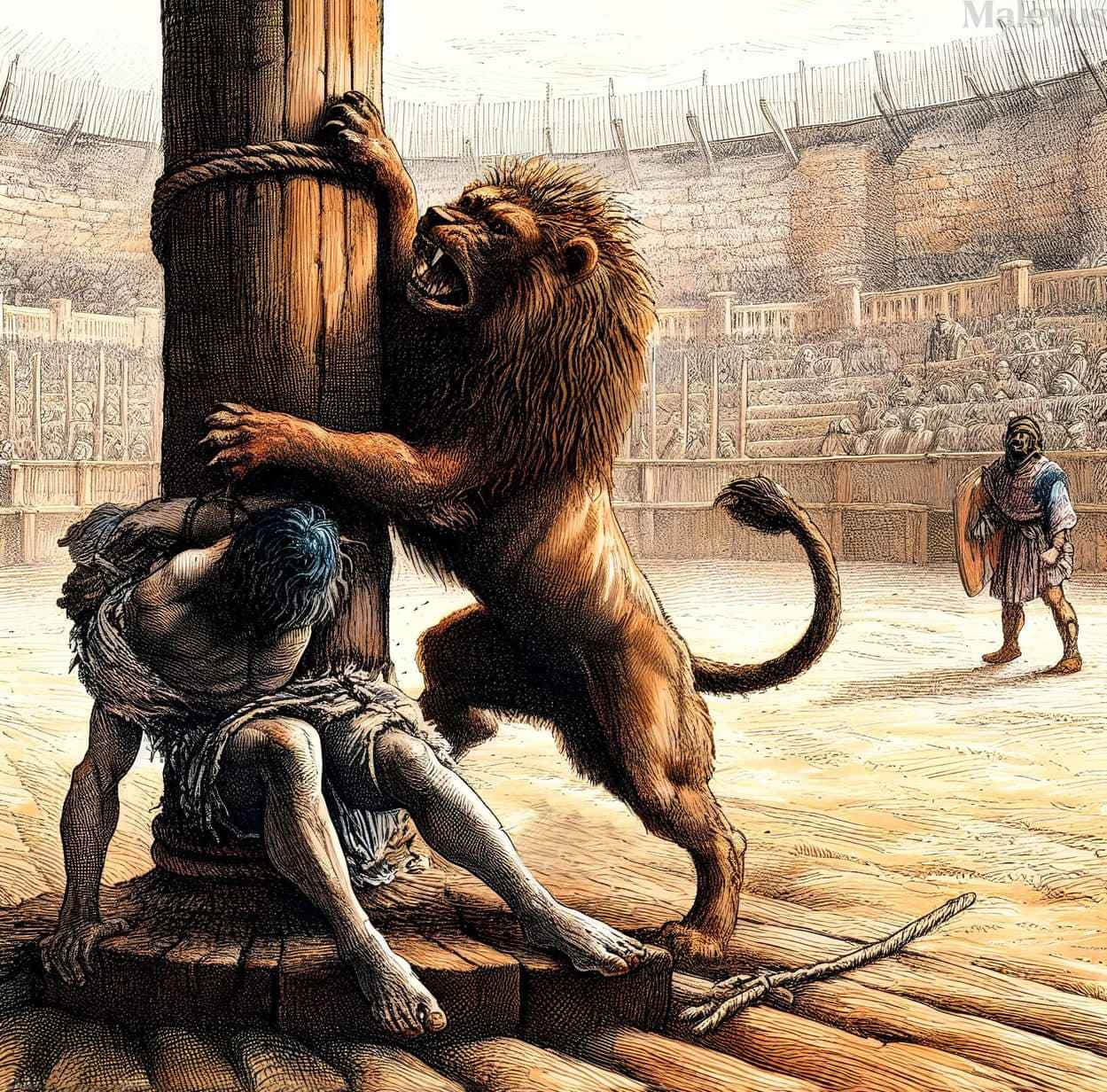

The Death of Gladiators in the Arena – A Favorite Spectacle of the Romans

A wounded gladiator falls to the sand. The other warrior raises his sword over him and looks at the stands of the Colosseum. The roaring crowd gives the thumbs-down gesture. Blood spurts. This is the image often painted by films about Ancient Rome. However, it wasn’t exactly like that.

To begin with, the Romans’ favorite spectacle wasn’t actually gladiatorial combat, but chariot races. While the Colosseum could hold “only” 50,000 spectators, the Circus Maximus, according to modern estimates, could accommodate about 150,000 Romans.

The extent to which the inhabitants of the Eternal City loved chariot races is illustrated by the fact that the Roman charioteer Gaius Appuleius Diocles is considered the highest-paid athlete in history. Over his lifetime, he earned nearly 36 million sesterces, which is roughly equivalent to 2.6 tons of gold. Peter Struck, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, estimates that today Diocles would have a fortune of about 15 billion dollars.

It’s also important to mention that most often in the arena, it wasn’t people but animals—often exotic ones—that were killed: lions, panthers, leopards, lynxes, elephants, rhinoceroses, and others. Major gladiatorial battles, like naumachia, could only be organized by emperors.

As for the likelihood of a gladiator dying in battle, it was about 1 in 10. Gladiators were specially bought and trained for combat, and some of them were even free men. Gladiators wore good armor, and in the case of injury in the arena, they were usually granted mercy.

It should also be noted that we don’t quite understand the gestures used in the arenas correctly. There is no unanimous opinion on what the extended thumb meant—whether it symbolized death or life. It is certain that the crowd didn’t decide the fate of the wounded; this was done by the emperor or, in his absence, the organizer of the games. Most likely, mercy was symbolized by a clenched fist, representing a sword sheathed in its scabbard, while the thumb, regardless of its position, likely meant a death sentence.

Nero Set Fire to Rome

One of the most famous myths in Roman history—that the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD was caused by Emperor Nero (37–68 AD)—can be traced back to Roman historians themselves. The first to write about it was Suetonius (70–122 AD), who spoke just as unflatteringly of Nero as he did of his predecessor Caligula.

Somebody in conversation saying—“Nay,” said he, “let it be while I am living” [emou xontos]. And he acted accordingly: for, pretending to be disgusted with the old buildings, and the narrow and winding streets, he set the city on fire so openly, that many of consular rank caught his own household servants on their property with tow, and (368) torches in their hands, but durst not meddle with them. There being near his Golden House some granaries, the site of which he exceedingly coveted, they were battered as if with machines of war, and set on fire, the walls being built of stone.

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, The Life of the Twelve Caesars, Book Six, Nero.

“Then followed a terrible calamity, whether accidental or instigated by the will of the princeps is not known (both views are supported by sources), but, in any case, it was the most severe and relentless of all the disasters ever to befall this city at the mercy of raging flames.”

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, Annals, Book XV.

To meet the needs of those displaced by the fire and left without shelter, Nero opened the Field of Mars, all the buildings associated with Agrippa, as well as his own gardens. Additionally, he hastily erected structures to accommodate the homeless masses. Food was brought from Ostia and nearby towns, and the price of grain was reduced to three sesterces.

Historians tend to agree with Tacitus. At the time, Rome was extremely overpopulated, and there were many flammable buildings. There is no direct evidence that Nero caused the fire (he wasn’t even in Rome when it started). On the one hand, upon learning about the fire, he helped the victims and developed a new building plan to prevent such fires in the future. On the other hand, soon after the fire, Nero began constructing a massive palace complex on the ashes, which, even in its unfinished state, astonished contemporaries.

The Inhabitants of Ancient Rome Were Engulfed in Orgies and Feasts

It is traditionally believed that the lives of wealthy Romans were full of indulgent feasts and gluttony. However, the reality was not quite like that.

Roman society was extremely conservative and traditional. Great importance was placed on mos maiorum—the “custom of the ancestors”—and modesty was one of the Roman virtues.

Since the alcohol content in wine (the primary drink of the time) was high, it was diluted with water before consumption. Drinking undiluted wine or in excessive amounts was considered the habit of barbarians and provincials.

Romans also washed their hands before meals and used napkins. They ate reclining, mostly using their hands. Bones and other inedible leftovers were thrown on the floor, which slaves later swept away. The food was fairly modest: the diet of wealthy people consisted mostly of vegetables, berries, game, grains, and poultry. During a feast, guests might entertain themselves with gambling.

However, moderation in food gradually disappeared during the late Republic. The tables of wealthy Romans began to feature delicacies like peacocks and flamingos. At the same time, morals became coarser, and gluttony and drunkenness became the norm. Still, this applied only to a narrow segment of the richest members of Roman society.

When it comes to orgies, the situation is also not so clear-cut. Ancient ethics viewed sexuality and its expressions differently. For example, the depiction of the phallus was not considered indecent, as it symbolized fertility and played an important role in the cults of agricultural gods.

At the same time, marriage held great significance for Romans—this was one of the differences between Rome and Ancient Greece. Roman women had more rights than Greek women, but also more responsibilities and accountability (for example, they were personally responsible for infidelity).

The Roman Empire Was the Largest in History

From the start, Romans were a nation of warriors. They conquered much of Europe and made the Mediterranean mare nostrum (“our sea”). At the height of its power, the Roman Empire stretched from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, but it was not the largest or greatest empire in history.

In terms of land area, the Roman Empire does not even rank among the top twenty largest states in history, falling behind, for example, the British, Mongol, and Russian empires.

Moreover, Rome does not rank in the top three largest states of antiquity. It was smaller than the contemporary Han Chinese state and the Hunnic Empire, from which the Han Chinese protected themselves with the Great Wall of China. The Roman Empire was also smaller than the earlier Achaemenid (Persian) Empire and the empire of Alexander the Great.

Roman Legionnaires Wore Red Clothing and Armor

In films and TV shows, Roman soldiers are always dressed in red. Indeed, such uniforms could help distinguish between friend and foe in battle, as well as exert psychological pressure on the enemy. However, in reality, there is no evidence that Roman legionnaires wore uniform scarlet equipment.

Red and purple clothing was only accessible to wealthy Romans and those in high positions. Martial, for example, wrote that red clothing was very rare. Therefore, unlike commanders, an ordinary soldier was unlikely to wear a bright tunic.

Legionnaires took care of their clothing themselves: they either bought it or received it in parcels from relatives. Typically, Roman soldiers wore short tunics, mostly made of wool. In the northern provinces, soldiers wore warmer tunics with long sleeves. A cloak (sagum) protected them from bad weather.

Although scarlet was the color of the god of war, Mars, the legionnaires’ clothing was most likely the natural color of wool: white, gray, brown, or black.