From the monk’s chant, praising God six hours a day, to the improvisations of a trouvère or troubadour, music’s omnipresence gave rhythm to daily life in the Middle Ages, in both the collective and private spheres. Yet medieval society didn’t think in terms of music; it thought in terms of music, which was seen as the keystone of Christian society in the West.

The result was a philosophical conception inherited from Greco-Latin antiquity and adapted to Christianity by the Church Fathers, making music as much an art as a mathematical, philosophical, and divine science, contributing through its harmony to the order of the world.

The Greco-Latin Heritage of Music in the Middle Ages

From Greek antiquity until the 16th century, a theory persisted that the universe is governed by harmonious numerical relationships and that the distances between planets are distributed according to musical proportions. This is traditionally known as the music or harmony of the spheres. At that time, only seven planets (Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) were known to orbit around the Earth; it wasn’t until Nicolaus Copernicus introduced heliocentrism in the 16th century that planets were understood to orbit around the Sun, corresponding to the seven musical intervals (excluding the octave) from a mathematical perspective.

This concept of cosmic music originated from Pythagoreanism and gained popularity among Greek philosophers, notably through Plato in his Timaeus and Republic as well as through Aristotle. The theory of the harmony of the spheres flourished subsequently under the pen of illustrious Latin authors such as Pliny or Cicero and remained vibrant in neo-Pythagorean and neo-Platonic schools with authors like Macrobius or Martianus Capella.

Primarily, it was the philosopher Boethius who synthesized around 510 AD the fundamental principles of Pythagorean and Platonic theory. His treatise, De institutione musica, became an indispensable reference throughout the Middle Ages. Indeed, his work was elevated to the rank of a “best-seller” among medieval musicologists and appeared to be the reference manual in musical education at the University of Paris in the 13th century.

In it, he categorizes music into three categories: musica mundana, musica humana, and musica instrumentalis.

The first, the music of the world (the harmony of the spheres), is at the top, harmoniously ordering the universe. The human body produces music, which is a harmonic relationship between the soul and the body. The latter characterizes music from instruments and voice; it is the only music perceptible a priori by the senses. Thus, while Boethius distinguishes musical practices linked to the sensible domain, he presents music primarily as a speculative and rational science organized around numbers.

A Mathematical Science?

As strange as it may seem to us today, music in the Middle Ages was not only taught as an artistic discipline but primarily as a mathematical discipline. For Boethius, only the theoretical aspects of music are worthy of study since musical practice falls under the manual labor of the artisan, instinct, and servitude. His treatise examines the various types of proportions, consonances, and dissonances based on their mathematical nature.

This conception of music as a mathematical science was taught throughout the Middle Ages, mainly within the quadrivium of the liberal arts.

In medieval universities, every “student” begins their curriculum with a common foundation of disciplines: the study of the liberal arts, divided into two categories: the trivium and the quadrivium. The trivium brings together language subjects: grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric. As for the quadrivium, it encompasses the four mathematical sciences: arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music.

However, music sometimes occupies a shifting place between the trivium and the quadrivium, as mastery of singing resembles mastery of speech and thus rhetoric. Furthermore, in addition to Boethius’s writings, another musical treatise universally known and used during the Middle Ages is Saint Augustine’s De musica. This latter, bishop of Hippo in the 4th century, considers music the “science of audible number,” allowing for proper modulation.

Consequently, he undeniably places this discipline on the side of mathematics, but he also understands music as the mirror of universal harmony, in other words, the reflection of divine beauty.

From Spiritual Science to Musical Practice

For Christian theorists of the Middle Ages, music allows reason to rise to the contemplation of divine beauty and wisdom. From a mathematical science, music is considered a spiritual and philosophical science that enables one to approach the divine. This explains its omnipresence in medieval liturgy.

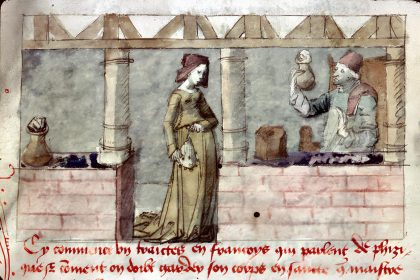

But this conception of music thus requires resorting to musical practice. The encyclopedist Vincent de Beauvais in the 13th century summarized music from both a theoretical and physical point of view, focusing on describing strictly musical aspects of the discipline such as rhythm, melodies, and musical instruments. He follows in the footsteps of the famous 11th-century musicologist Guy d’Arezzo, inventor of the Western musical notation system, who partly rejects Boethius’ treatise, judging it more useful to the philosopher than to the singer.

Many medieval thinkers, mainly from the late 13th century onwards, subsequently distanced themselves from the founding texts of musical conception, placing practical aspects above theory. For them, music should serve human pleasure and not be limited to the praises of God. This rupture leads to theological debates on the place and role of music. We can think of Thomas Aquinas, who, in his Summa Theologica, accepts the pleasures and diversions that a juggler can bring moderately for the common good of society.

Finally, let us mention the formula of the most famous French composer of the 14th century, Guillaume de Machaut: “And music is a science that wants us to laugh, sing, and dance; there is no cure for melancholy.” The change in how people perceived music at the end of the Middle Ages is comparable to the Ars Nova’s representation of artistic development. These changes also reveal the duality of this discipline.

Music in the Middle Ages: A Multifaceted Concept

Throughout the Western Middle Ages, the Christian view of music presented a notable contradiction that dates back to ancient Greek times. In the 13th century, the Dominican preacher Étienne de Bourbon recounts an episode from Homer’s Odyssey in which Ulysses, to resist the enchanting songs of the sirens, plugs his ears.

Through this tale, Étienne de Bourbon aims to caution believers about the psychological impact of music. In medieval thought, music was believed to have the power to influence the human soul, which could be both beneficial and harmful to Christian society. While medieval musicians and physicians recognized music’s therapeutic potential, they also warned of its unpredictable and potentially dangerous effects. Not all music was deemed good; the Church Fathers vehemently opposed harmful music, viewing it as a symbol of pagan decadence and effeminacy. Clement of Alexandria sought to ban artificial music that could lead to idolatry, while John Chrysostom warned against its seductive allure, particularly the voices of women.

One of the greatest concerns for Christian theologians was the figure of the entertainer, whether a juggler, troubadour, comedian, or similar, often regarded as a performer of the devil who could not be buried in consecrated ground. This viewpoint, however, was not universal throughout the Middle Ages.

Some medieval theologians admired the oratory and musical talents of entertainers, even likening the biblical figure of King David to a “juggler of God.” Medieval clerical literature abounds with tales where entertainers, through their art, could lead the faithful to divine faith. This duality exemplifies the ongoing clash of perspectives on music. While theologians saw music as a means to praise divine greatness, it also held the potential to lead believers astray into sin. Musical practice could either contribute to salvation or damnation.

The medieval understanding of music was diverse, encompassing various forms such as learned or aristocratic music, philosophical discourse, and artistic expression, whether oral or written, sacred or profane. It defies precise definition, evolving over time and presenting historians with a rich tapestry of cultural and societal issues from the Middle Ages.