4,300 to 7,000 wounded in the ranks of the Grande Armée by the evening of Eylau, more than 21,000 wounded by the evening of the Moscow! The dark side of these Napoleonic victories are the mass graves, the field ambulances where amputations are performed in assembly-line fashion, and the makeshift hospitals where the wounded are crowded together. Here, the soldier faces new enemies: gas gangrene, tetanus, dysentery, fevers… To save those who can still be helped, the medical service established an entire support network from the battlefield to rear facilities.

Triage System

Napoleon: Medicine, and Surgery

Napoleon Bonaparte was always very skeptical of medicine, ambivalent about its true benefits, and often mocking of those who practiced it. He enjoyed teasing Corvisart and mocking remedies that did more harm to the patient than the illness itself. He still maintained at Saint Helena:

Our body is a machine for living, it is organized for that, it’s its nature; let life run its course, let it defend itself, it will do more than if you paralyze it by burdening it with remedies. Our body is like a perfect watch, which is meant to run for a certain time; the watchmaker does not have the ability to open it, he can only handle it blindly and clumsily. For every one who, by tormenting it with odd instruments, manages to do good, how many ignorant ones destroy it…

Dr. Godlewski acknowledged that Napoleon’s distrust of the medicine of his time was not entirely unfounded. While the early 19th century was the age of great surgeons, it was not yet the age of great physicians, which would only come with the discoveries of Pasteur, radiology, and bacteriology. Indeed, while he despised medicine, Napoleon held surgery in high esteem, particularly the army medical corps surgeons who risked their lives to save others. Napoleon himself was even personally drawn to the field and reportedly attended anatomy courses three times from April to July 1792, before his military career took off.

Treating the Army in Garrison

Each regiment had a few surgeons to care for soldiers in garrison. The most common cases were “fevers,” a generic term that covered various diseases such as influenza, meningitis, and dysentery, often caused by poor water quality and food. If necessary, the patient was sent to a military hospital, or even a civilian hospital in certain special units like the Departmental Reserve Companies. Other treatments were conducted directly at the barracks, particularly for cases of scabies or venereal diseases.

Field Ambulances

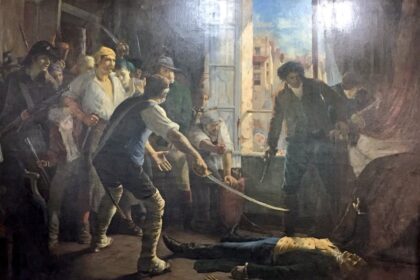

The massive use of artillery is the cause of the worst injuries found in 19th-century armies. Surgeon-Major de La Flize reports in his memoirs some colder and darker realities than the epic paintings of the same period might suggest:

I remember some [of the horrific wounds] that particularly struck me. An artilleryman had three-quarters of his face torn off by a cannonball; he had only one eye left but had not lost consciousness and communicated by signs; he was horrible to look at. Another artilleryman had both thighs and one hand blown off and the other arm broken near the shoulder; he could still speak and asked me for brandy; I gave him a drink, and he expired immediately after. […] A young artillery non-commissioned officer, who was on guard near the guns, had his hands resting on the pommel of his saddle when a cannonball crushed both of them. He cried like a child and called for his mother.

To save those who can be saved, and ensure the morale of all, the Grande Armée quickly equipped itself with an important health service structured by a network of ambulances. In the Grande Armée, an ambulance refers to all centers of varying importance responsible for providing care to those in need, whether at the regimental or army corps level. There are five distinct types of ambulances:

- The regimental ambulance, closest to the fighting, where first aid is provided to the wounded, but also all operations requiring urgent intervention: from amputation to trepanation… The infantry division ambulance with its two wagons takes charge of the wounded at the division level, theoretically composed of six surgeons, four pharmacists, and four employees.

- The army corps ambulance is a mounted ambulance, called a light ambulance, which can deploy and redeploy as needed. It can form an ambulance depot just behind the front line to quickly evacuate the wounded during battle. It can also form ambulance divisions to reinforce division ambulances or form ambulance sections responsible for supporting small detached units or deployed at outposts. In the case of ambulance sections, the unit carries provisions in addition to its traditional equipment of dressings and medical instruments.

- The ambulance reserve, directly attached to the general headquarters, is a strategic reserve composed of about fifty surgeons (under the command of a chief surgeon) on horseback or in carriages to reinforce as quickly as possible any other ambulance that might need it.

- Finally, the Emperor’s ambulance is responsible for the sovereign’s health. Napoleon always has a surgeon, a doctor, a pharmacist, and a few nurses ready to intervene in case the Emperor is wounded. They have a wagon with all the necessary equipment. Although often exposed, Napoleon was very lucky on the battlefield. He was nevertheless wounded on April 23, 1809, during the Battle of Ratisbon in Austria. A bullet fired from the city walls wounded him in the right heel, grazing the Achilles tendon. It was surgeon Yvan who cut the Emperor’s boot and dressed the wound before he remounted his horse to keep up appearances for the enemy.

Being Wounded on the Battlefield

Even though in practice it sometimes happened, soldiers were generally forbidden during battle from going to assist the wounded. Doing so risked weakening the ranks to the enemy’s advantage. While some wounded soldiers managed to reach the ambulance on their own, others were cared for on-site by the medical service. To facilitate this, Larrey set up “flying ambulances (ambulance volante),” two- or four-wheeled carts mounted on springs (to cushion the shocks somewhat), capable of carrying two to four wounded soldiers lying on mobile beds. These flying ambulances allowed for the rapid evacuation of the wounded after they had received first aid from surgeons following the ambulance on horseback.

However, for cost reasons, this system did not last during the Empire, except within the Imperial Guard, where Larrey operated. Along similar lines, Pierre-François Percy introduced the Wurst, long sausage-shaped carts (hence the name, which means “sausage” in German) that surgeons would straddle like a horse to quickly reach those in need. They were used during the Swiss, Danube, and German campaigns. But more commonly, toward the end, the Grande Armée employed stretcher-bearers equipped with pikes that could be transformed into stretchers. Da La Flize recounts:

The stretcher-bearers were then ordered to construct stretchers. These men, two by two, unrolled the straps from their packs, unscrewed the iron head of their pikes, inserted the pole into a slip knot formed with the straps, and fixed their canvas belts in place. The stretcher-bearers then headed towards the battlefield.

The wounded who were not evacuated during the battle usually spent the night without help and had to wait until the next day for the evacuations to resume. Further back, the first-aid posts were improvised, either in pre-existing buildings or under tents on some straw gathered from nearby. The situation was even more critical in winter, as during the Battle of Eylau, since these makeshift shelters offered little protection from the cold. It was at these first-aid posts where the diagnosis was made, and the wounded soldier came into the hands of the surgeons. A former officer of the Grande Armée, Elzéar Blaze, provides a nuanced account of the surgeons, acknowledging their bravery but also the lack of experience among newcomers who learned “on the job”:

The major surgeons were generally good practitioners. Amputating an arm or a leg was as easy for them as drinking a glass of water; I even knew some for whom the latter operation would have made them grimace. These gentlemen had great zeal, and were often seen on the battlefield assisting the wounded, risking their own lives. Many combined science with practice; for others, practice alone sufficed; but by constantly treating all kinds of wounds, with the same cases repeating every day, they knew as much as they needed to know.

But new young men constantly arrived from France, who, through connections or to avoid going into battle with a pack on their back, had somehow gotten a surgeon’s assistant certificate after three months at medical school. They then underwent a practical course in the army at the expense of the first unfortunates who fell into their hands, having escaped the cannon; the scalpel awaited them… and… well… It was, in truth, far worse than Scylla and Charybdis.

The chief surgeon of La Flize recounts in his memoirs the horror of mutilations and operations during the Battle of Borodino in 1812:

On that day of grim memory, how many cruel operations we performed! One cannot imagine the impression a wounded soldier has when the surgeon is forced to tell him that he is doomed unless one or two limbs are amputated. The unfortunate soul is reduced to submitting to his fate and preparing for horrific suffering. It is impossible to express the groans, the teeth grinding, torn from the wounded when a limb is shattered by a cannonball; the painful cries they let out when the surgeon exposes the limb, cuts through the muscles, severs the nerves, saws the bones, and slices the arteries, with blood splattering everywhere. We could say that we were literally drenched in blood, although we were not responsible for its flow, but were instead striving to stop it.

In the French army, amputations were frequent. During the Battle of Borodino, the surgeon Larrey stood for 36 consecutive hours and performed 200 amputations himself! For this experienced surgeon, it took only 4 to 5 minutes to amputate a shoulder. In the absence of anesthetics, the speed of the operation was crucial to minimizing the sufferings of the wounded.

Often, the patient was given just a little alcohol to drink. Sometimes, he clenched his clay pipe to endure the pain: if the wounded died during the operation, his jaw would sometimes loosen, causing the pipe to fall to the ground and break — the origin of the expression ‘to break one’s pipe’ (a French idiom meaning ‘to die’). These rapid and repeated amputations may seem cruel, but they often saved the wounded who would otherwise have died from gangrene.

This extensive resort to amputation was also justified by the very particular context of wartime surgery: if the wounded soldier survived, he would be transported along rough roads and cared for by inexperienced personnel who would be unable to properly manage a serious wound requiring regular dressing — the stump offered a better chance of survival. Aside from a few wealthy exceptions, like generals who could afford luxury prosthetics, most amputated soldiers spent the rest of their lives with a wooden leg (sometimes jointed at the knee), or a simple crutch. Some, unable to afford or bear such prosthetics, were left with crutches or canes.

The soldier’s recovery was not the end of his misfortunes. On the battlefield of Borodino, La Flize reports that there was a lack of food for the wounded. However, the Guard was better fed. As the army resumed its march, the wounded were left in field hospitals, sometimes tens of kilometers from the battlefield, and not all survived the journey. Percy, recounting the arrival of a convoy of wounded during the Peninsular War, wrote:

It had been five days since most of them had left the cart that had served both as their transport and their bed; their straw was rotting; some had a mattress under them, soiled with the pus from their wounds and their excrement. […] The stench was unbearable. The wounds had not been dressed in several days, or had been done so poorly; many were already gangrenous…

Upon their arrival, they were greeted under conditions that varied greatly depending on the location and time. In 1809, a corps of hospital nurses was even created, deployed in Austria, Spain, and Italy. These nurses were unarmed, not even carrying a small sword, with Napoleon hoping this would ensure their neutrality on the battlefield—an initiative later adopted by the Red Cross. This neutrality was reinforced by the fact that French doctors treated all wounded, regardless of nationality. However, no written agreement on the inviolability of military hospitals was reached during the Napoleonic wars, despite an attempt that Austria rejected in 1800.

Regardless, these hospitals are remembered grimly: the wounded often lacked food, heating, especially during the Russian campaign, and typhus outbreaks occurred frequently (such as in Mainz in 1813). There were also personnel shortages (if there were no local staff, particularly nuns, prisoners were requisitioned without hesitation), as well as shortages of medicine and bandages. At the Mojaïsk hospital in 1812, the wounded were bandaged with straw due to the lack of cloth or bandages.

However, these dark descriptions should be tempered by acknowledging that there were well-run field hospitals under the Empire, such as in Burgos in 1810, which had a bathroom, fans for the summer, and stoves for the winter. Despite the difficult conditions and frequent improvisation, it is notable that only 10% of the wounded who reached the hospital died. To understand this figure, it must be considered that hospitals treated not only the war wounded but also the sick in general.

In the end, our view of the healthcare services during campaigns under the First Empire must be nuanced. It was run by dedicated, qualified, and dynamic men who constantly had to make do with limited material and human resources. Napoleon, who always favored short campaigns carried out by fast-moving armies, ultimately invested little in modernizing the healthcare service, which did not allow for maintaining a sufficient and experienced staff. Young surgeons gained experience, and nurses were often neophytes, more or less voluntary depending on the circumstances. Observing the shortage of nurses at Eylau on February 9, 1807, Napoleon exclaimed in frustration: “What an organization! What barbarity!” Surgeon Lombard then dared to explain the lack of enthusiasm for joining the healthcare service:

Sire, when one is sure that in peacetime, no matter how well one performed during the most difficult and perilous war, they will be dismissed, it is hard to be zealous and decide to follow an army as an employee or nurse; this very title upon returning to France will be a terrible recommendation.

One can indeed speak of a lack of recognition for the healthcare service, which, straddling the civilian and military spheres, remained overshadowed by the latter. Napoleon distributed the Legion of Honor to them sparingly (ten surgeons were decorated after Eylau, two of whom died of exhaustion a few days later…) and forbade surgeons from wearing epaulets, which he believed should be reserved for true soldiers (although the surgeons of the Guard granted themselves this right…). Nonetheless, it was these few years of war that allowed surgery to develop at an unprecedented speed.