Pertinax, born to a freedman, made history as the first Roman emperor with humble origins. A military career under the rule of Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius served as a milestone on his path to the throne. He earned distinction in conflicts against the Parthians and Marcomanni, ascended to the Senate, served as consul twice (in 175 and 192 CE), governed multiple provinces, and assumed the role of prefect of Rome in 190 CE.

Pertinax, however, gained power after conspirators killed Commodus. He became Emperor unexpectedly and tried to rule in accordance with the Senate. In less than three months, he instituted austerity measures to improve the empire’s finances, pardoned anyone guilty of “Lèse-majesté,” and revived the court system.

Yet, the Praetorian Guard, who still had warm feelings for Commodus and worried that their privileges would be taken away under the new emperor, posed a significant obstacle for Pertinax. Despite his best efforts to win their support, the Praetorians murdered Pertinax in the comfort of his own palace.

Lucius Septimius Severus, governor of Upper Pannonia, claimed the mantle of vengeance on behalf of the late emperor and used this as an excuse to spark a civil war. Pertinax was posthumously deified after Severus’ victory, and his son became the high priest of his cult.

Key Takeaways: Emperor Pertinax

- He served as a military tribune in Britain and Dacia and held various commands in different provinces.

- In 192 CE, following the murder of Emperor Commodus, Pertinax was appointed as the new emperor by the Praetorian Guard, who were responsible for the emperor’s security.

- Pertinax’s strict measures and attempts to curb corruption led to discontent among the Praetorian Guard, who eventually turned against him.

- On March 28, 193 CE, after just 86 days in power, Pertinax was assassinated by mutinous soldiers.

Early Years of Pertinax

On August 1, 126, on the Apennine land his mother owned near the town of Alba Pompeia in Liguria, Publius Helvius Pertinax entered the world. “From a simple and insignificant family,” Herodian writes about the future emperor. According to Julius Capitolinus, Publius’ father was a freedman and trader named Helvius Successus. Helvius Successus named his son Pertinax (Latin for “persistent, persevering, tenacious“) to honor the fact that he had been involved in the wool trade nonstop throughout his life.

Successus worked hard to provide a quality education for his son. The future emperor, Pertinax, studied grammar under the tutelage of Gaius Sulpicius Apollinaris (the teacher of Aulus Gellius) but found that teaching was not lucrative enough to sustain his family. According to Julius Capitolinus, his father’s patron, consular Lollian Avita, helped him get promoted to the rank of centurion.

According to Cassius Dio, he became a cavalry tribune thanks to the help of Claudius Pompeianus. However, some scholars point out that the inscription found in Brühl and dedicated to Pertinax does not mention the position of centurion. Lollianus Avitus is considered to have merely attempted to promote Publius Helvius to the rank of centurion but ultimately failed.

Eventually, Pertinax became the commander of the IVth Gallic Cohort in Syria. This occurred during the reign of Antoninus Pius, that is, before 161 CE; historiography has a more precise dating of about 157 CE. This job provided Publius’ ticket into the equestrian world, but it was otherwise meaningless. This is demonstrated by an incident recounted by Julius Capitolinus: because Pertinax used the public postal service without official authorization to reach the province, the Syrian governor forced him to walk from Antioch to his place of service.

In the Roman-Parthian War, which lasted from 161 to 166, Pertinax served “because of his zeal” under the command of Lucius Verus. He may have only been involved in the conflict’s first stages, which concluded successfully for Rome (the Parthians were pushed out of Syria) in 163 or early 164 CE.

As a tribune of the Victorious Sixth Legion based in Eboraca, Publius Helvius was sent to Britain in 164, 165, or 166 CE. Later on, in Moesia, Pertinax took command of the mounted auxiliary cohort of either the First or Second Tungraean Legion. Historiography speculates that Publius headed an equestrian detachment in Pannonia under Claudius Pompeianus, who controlled the province from 165 to 167 CE, based on his name in an inscription discovered in Sirmia.

After that (likely in 166 or 167 CE), he oversaw food distribution on the Aemilian road between Ariminus and Placentia, and then (possibly in 167 or early 168 CE), he commanded the Germanic fleet on the Rhine, and finally he was transferred from Germany to Dacia, where his salary reportedly increased to 200,000 sestertii, as recorded by Julius Capitolinus.

It is not clear what position Publius held in Dacia; in historiography, there are assumptions that it was a procuratorate or some extraordinary post with the powers of legate-propraetor. Historians disagree on whether the Dacian appointment occurred in 168, 169, or 170 CE.

In Senior Positions

Pertinax was “through the machinations of certain persons he came to be distrusted by Marcus and was removed from this post,” as Julius Capitolinus recalls, abruptly ending his career in Dacia. No one knows what happened. Scholars of antiquity can only speculate that certain members of the imperial elite were unhappy with Publius’ performance and plotted to have him removed. It’s also not known for how long Pertinax has been retired.

His patron, Claudius Pompeianus, is said to have married Marcus Aurelius’ daughter (the widow of Lucius Verus) and subsequently promoted his creature, although neither the wedding nor its date are known. We only know that Publius served as Pompeianus’ “future assistant” in “command of military units,” where he did well enough to be promoted to the senatorial estate.

His assistance to Pompeianus likely came in the form of leading auxiliary forces during the Marcomannic Wars (which began in 169, 170, or 171, depending on the source). The invasion of Northern Italy by the Marcomanni and Quadi might be repulsed with the help of Pertinax, and then the retreating enemy could be pursued to the Danube border, most likely in Pannonia. Marcus Aurelius “gave him the title of former praetor and put him at the head of the first legion” with a post in Pannonia as a reward for his efforts.

Publius led this legion in wars across the Danube against the Quads (likely in 171 or 172) and the Sarmatians (perhaps in 174 or 175). He also helped free the provinces of Raetia and Noricum (Noricus) from barbarian control. As a reward for his “outstanding zeal,” the future emperor was named consul-suffect in 175 with another victorious commander, Marcus Didius Julianus, who had just beaten the Germanic tribe of the Chauci.

Marcus Aurelius learned about Avidius Cassius’ insurrection in the East (spring 175) after the Romans had gained a full victory in the Marcomannic War and were in the midst of forming two new provinces beyond the Danube. Even though Pertinax was one of the commanders who had to put down the uprising, the conflict was swiftly resolved once the rebel was killed. The Emperor then took Publius Helvius along on an inspection tour of the eastern provinces.

Lower Moesia (176–177), Upper Moesia (177), and Dacia (177–179 or 177–178) were the three Danubian provinces over which he served as legate (imperial governor) for the following three years. The new border battles on the Danube, which only ceased when Marcus Aurelius’ son Commodus became emperor in 180, may have contributed to this unusually quick turnover of leadership. Pertinax was successful in establishing defenses for his provinces, ensuring that peace and order would be maintained.

Pertinax served as governor of Syria, a strategically important province in the Roman East, during the years 178 and 181. His son, Publius, was likely born there as well. Due to Pertinax’s association with numerous participants in the then-uncovered plot Lucilla, the prefect of the Praetorium, Sextus Tigidius Perennis, quickly ordered him to depart for a Ligurian estate upon his return to Rome in 182.

The time spent in exile was three years. Commodus remembered Pertinax after Perennis’ assassination in 185 and appointed him legate in Britain, where the situation was already precarious due to discontent in the three local legions caused by the brutality of the previous governor, Ulpius Marcellus. Despite pressure from the troops, Publius held firm.

In an effort to restore order, Julius Capitolinus writes that “after his arrival there, he kept the soldiers from any revolt, for they wished to set up some other man as emperor, preferably Pertinax himself.”

On the other hand, we learn from the same source that the legionaries nearly murdered the governor once (he was rescued only because he was lying among the corpses) and that Publius urged the emperor to find a replacement for him because of the troops’ too-hostile attitude.

After returning to Rome in 187, Pertinax became the praefectus alimentorum, the government’s food trustee. He “endured many rebellions, drawing vigor from the temple of the Heavenly Goddess” after being appointed proconsul of the province of Africa in 188. In 189, Pertinax moved back to Italy, and the following year, he was given the prestigious office of prefect of Rome. During this time, Publius was quite close to Commodus, and in 192, he served as resident consul alongside the Emperor.

Pertinax on the Eve of Its Rise to Power

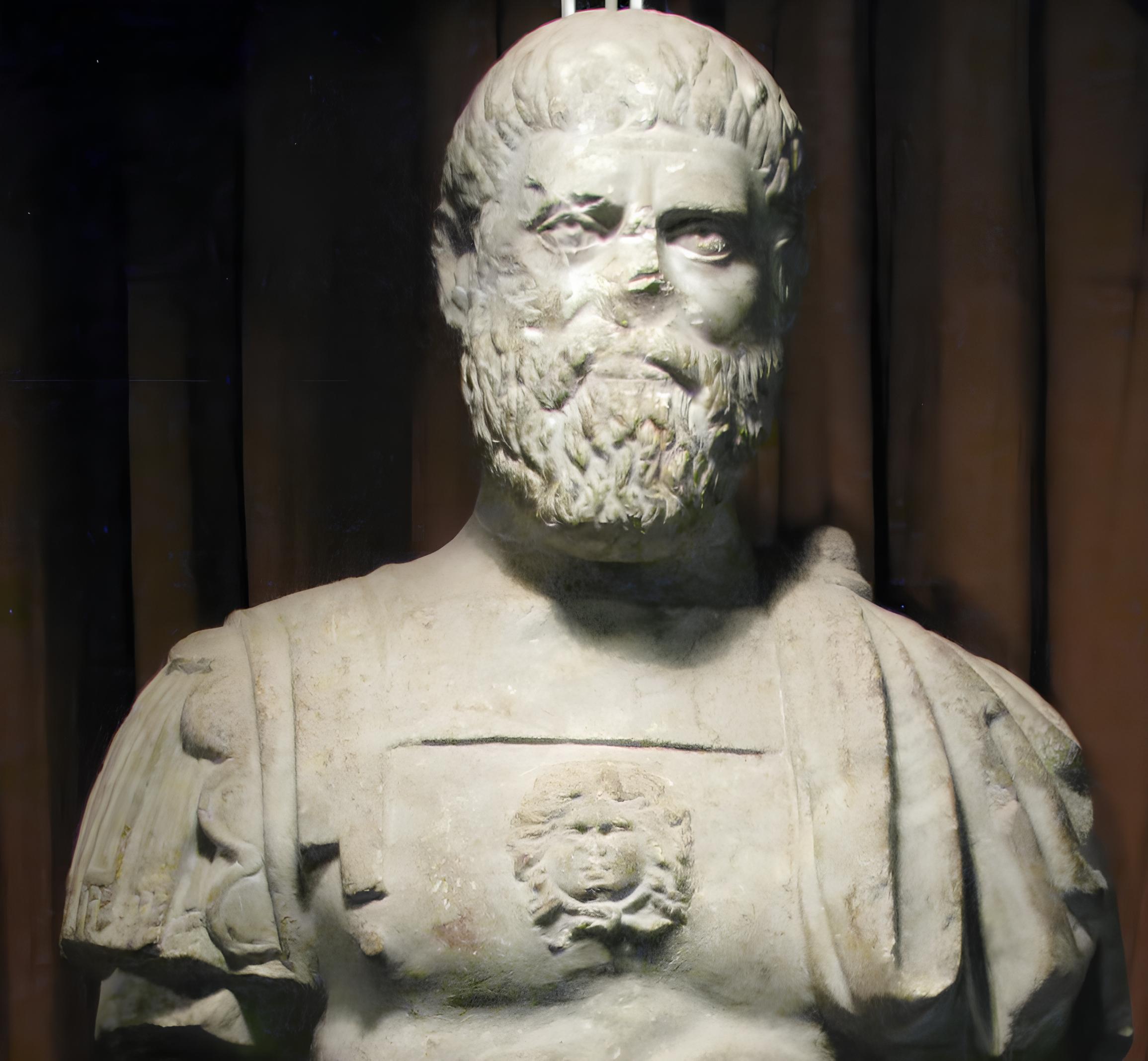

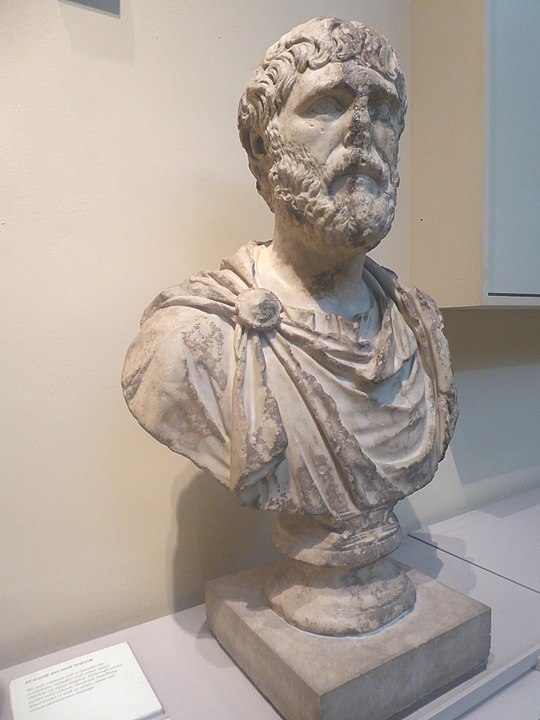

Pertinax was 66 years old when his life took a dramatic turn towards the end of 192. Julius Capitolinus described him as “an old man of venerable appearance, with a long beard, curly hair, a stout build, and a somewhat prominent belly,” and he was fairly tall. He was never thought of as simple-minded, even though he was not known for his eloquence and was more affectionate than kind.

Publius Helvius amassed a massive fortune through a combination of factors, including the viceroyalty in several provinces (including the very wealthy ones), the expansion of the cloth production he inherited from his father, trade conducted through his slaves, high-interest loans, and the seizure of land from insolvent debtors. It was said that while in service, he excused legionaries from work and sent his subordinates on business excursions in exchange for payment.

The wealthy Pertinax was also very thrifty, often to the point of miserliness. As a result, half-portions of lettuce and artichokes were offered at the feasts hosted by Publius. If he didn’t get anything tasty as a gift, he’d feed his pals (regardless of the amount of them there were) with nine pounds of steak divided into three courses. He always invited many people to the feast, but if they sent too much food, he would save it for the following day. All of our sources describe Pertinax as being exceedingly frugal.

He was the last of Marcus Aurelius’ “honorable friends” to live through the emperor’s death at age 192, and Herodian describes him as “a man of strong soul and in all respects courageous” who achieved great fame for his military successes. Cassius Dio describes Pertinax as courageous and knowledgeable, but he was unable to counter Publius’ quick rise to prominence.

Proclamation by the Emperor

There was a big problem on the horizon for the Roman Empire in the early 190s. Commodus put his attention on entertainment and gave his favorites, Perennis and Cleander, control of official affairs. He underestimated the Senate, leading to the execution of some members of that body because he feared they might turn against him. The Emperor maintained control by holding expensive parties, handing out money, and increasing privileges for the Praetorian Guard and the plebs of the city. Commodus did not want to go to battle with the barbarians and instead tried to appease them with presents of money.

All of this led to the treasury nearly running dry, a decline in military discipline, and widespread discontent among the aristocracy, which was exacerbated by the Emperor’s scandalous behavior (he went to the arena hundreds of times as a gladiator, was forced to refer to himself as “Hercules,” and earned a reputation as an extremely spoiled and reckless man).

Praetorian prefect Quintus Aemilius Laetus, mistress Marcia, and court manager Eclectus were all involved in a plot around the year’s end of 192. They attempted to poison Commodus on December 31, 192, and when that failed, they strangled him. Laetus and Eclectus, or their emissaries, then went to Pertinax and offered him absolute authority before the murder became public knowledge. According to Herodian, the conspirators chose Publius Helvius because he suited their ideal of a temperate elder who would assume power, so that both they themselves might be saved and all might rest from unbridled tyranny.

According to Herodian and Cassius Dio, Pertinax initially believed that Commodus had sent him to deliver the news of his demise. Even when he dispatched someone he trusted (either Livius Laurens or Fabius Cilo) to see Commodus’ corpse, he first hesitated to accept the news from the imperial palace.

After confirming the emperor’s death, Publius Helvius went to the Praetorian barracks to hear Laetus’ announcement that Commodus had died “from apoplexy” and that Pertinax had taken over as dictator. Despite their lack of excitement, the guards who remained faithful to the deceased emperor nonetheless declared Publius Augustus. This was due in part to the substantial payment of twelve thousand sesterces per soldier that was promised to them and in part to the pressure from the public outside the barracks, who were expressing their hatred of Commodus.

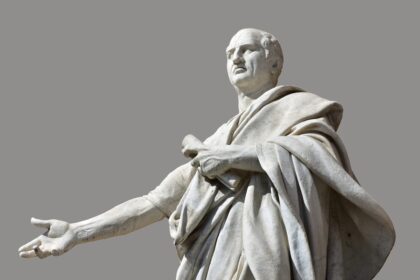

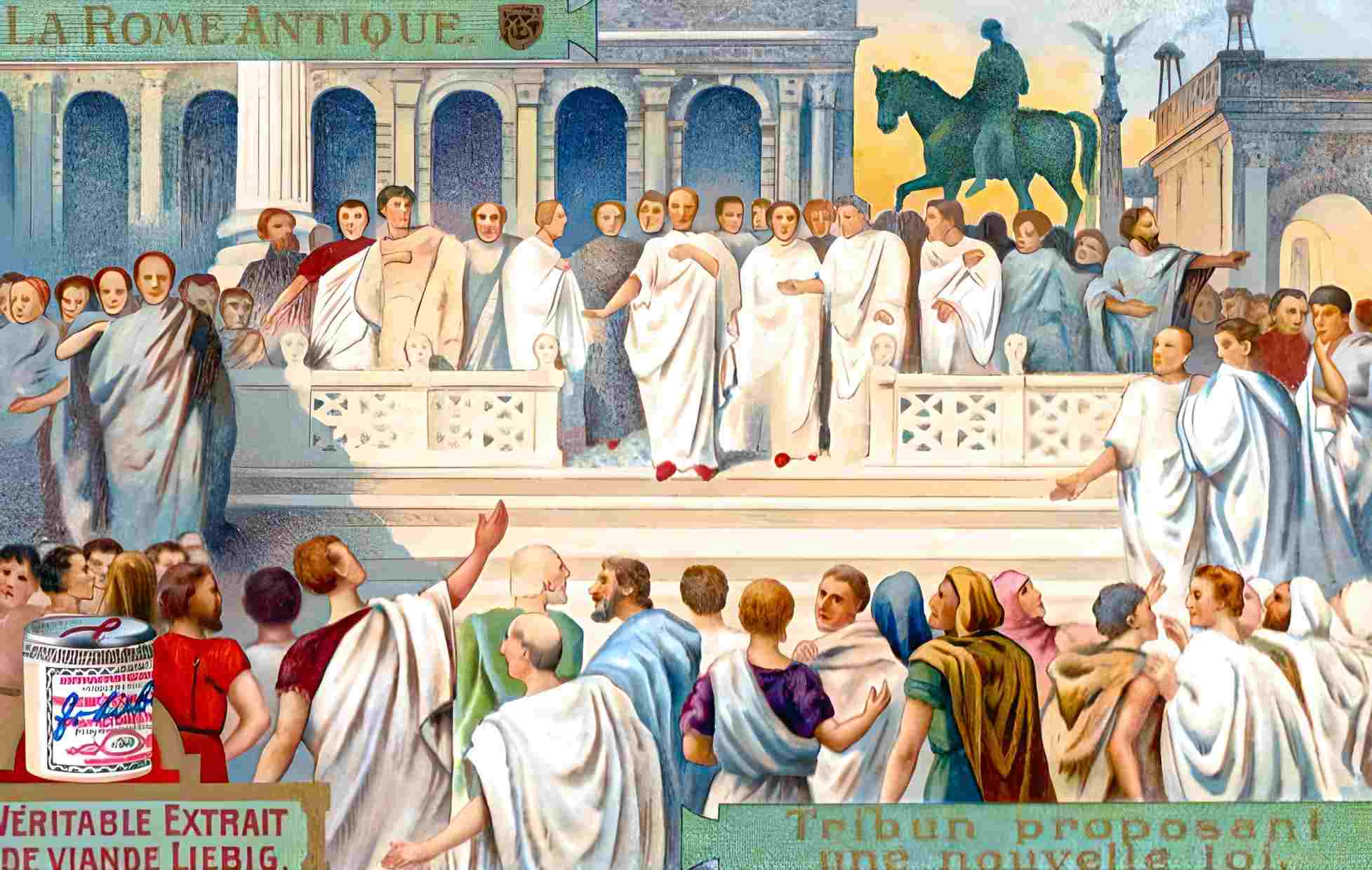

Pertinax made his way to the Senate from the barracks. He was quickly hailed as Augustus by the gathering curia, but Publius started to resist the position, claiming that he was too old and that there were more worthy and honorable contenders. Cassius Dio claims that in his first address to the senators, he said, “I have been proclaimed emperor by the soldiers, but I do not wish to rule.”

According to Herodianus, Pertinax proposed Mania Acilius Glabrio, the son-in-law of Marcus Aurelius Claudius Pompeianus, as consular instead of himself, but both men turned down the offer. Meanwhile, other senators kept trying to convince Publius to accept power. Afraid and unsure, he “ascended the imperial throne” at long last. Researchers believe the new emperor acted this way because he wanted to accept authority (at least nominally) from the Senate rather than the Praetorians or because he believed that absolute power should be left to representatives of the ancient patrician nobility.

At the same meeting, Publius Helvius received all the attributes of imperial power, including the powers of the proconsul, the right to four reports (that is, the right to put up to four questions in turn to a vote of senators), and the honorary nickname “Father of the Fatherland” (Pater patriae). At the same time, he refused the titles that Augusta and Caesar proposed for his wife and son, respectively (however, on the coins minted in Egypt, these titles still appeared). From the curia, Pertinax went to the Capitol, where he sacrificed to Jupiter and made the necessary vows. From that moment on, he was the ruler of the Roman state.

Beginning of Reign

Pertinax accepted a heavy inheritance. With only one million sestertius in the treasury as of January 1, 193, the imperial government was desperately short of the money it needed to pay the salaries of the military, feed the plebeians of the capital, and maintain the roads. Despite the introduction of additional taxes in Rome and the provinces, cuts to pensions and subsidies, the shifting of certain payments in kind, and the influx of cash through confiscations and the sale of privileges and posts, the state’s debts continued to rise.

Publius Helvius put an end to the extravagant spending at the imperial court by auctioning off the vast wealth that Commodus had amassed over a twelve-year period, as well as the belongings of the imperial slaves and freedmen. All taxes presented to Pertinax were his to keep, and he “set aside all squeamishness” to declare invalid the state’s maintenance payments for the previous nine days. Although Julius Capitolinus claimed that these actions would free the imperial treasury to settle all debts, experts now doubt that this is the case.

Publius Helvius made an attempt at a senate-based government. Soon after assuming power, he made it clear that the princeps and senators should work together to run the country, and he attended meetings often from then on. Furthermore, Publius’ actual behavior reinforced his unwillingness to execute senators. He followed the lead of the “Five Good Emperors” by declaring that state property was not his personal property, and he restored all private property that had been seized during Commodus to its rightful owners or heirs (for a price).

The soldiers and guards were given orders to “cease their willfulness towards the common people, not to carry clubs in their hands, and not to beat any passersby.” It seems that Pertinax attempted to make amends in the judicial system by reverting to the customary procedure of hearings with prosecutors and defense in place of the previously used arbitrary sentences based on imperial rescripts. Slaves found guilty of making a false denunciation were crucified on crosses, and all charges of “insult to majesty (Lèse-majesté)” were abandoned. Those banished because of such cases were permitted to return home, and those killed were rehabilitated posthumously.

War and disease during the preceding thirty years had already devastated Italy. In response, Pertinax started offering tax breaks to anybody who wanted to farm property that had been abandoned by its previous owners (agri deserti) for a period of 10 years. He got rid of tolls at bridges, ports, and riverbanks and put a lot of money into cleaning up and organizing public infrastructure.

All of these steps, combined with the capital’s distribution of 400 sesterces to every citizen, were meant to improve the living standards of small and medium-sized business owners and the poorest citizens. According to Julius Capitolinus, the austerity program was also a factor. When the emperor cut wasteful spending at the imperial court, he cut expenditures by almost half compared to the norm, and “everyone became abstemious” as a result.

During Pertinax’s reign, a variety of new inscriptions appeared on coins, including “Praiseworthy Piety,” “To the Guardian Gods,” “Gods Ancestors,” “Janus the Guardian,” and “Liberated Citizens.” This demonstrates Publius’ cautious approach to orthodox Roman doctrine. An imperial edict that increased the denarius’ weight from 2.22 to 2.75 grams and its silver content from 74% to 87% stabilized the financial system.

First Manifestations of Discontent

Even with the support of the plebs in the capital and the Senate on his side, Pertinax’s position was precarious at best. There was discontent even among the senators; in the first meeting of the consul, Quintus Pompeius Sosius Falco criticized the emperor for surrounding himself with “servants of Commodus in his crimes,” like Martius and Quintus Aemilius Laetus. Hedius Rufus Lollianus Gentianus later opposed the continuation of the high taxes imposed under Commodus. He spoke persuasively on behalf of a large number of senators but accomplished nothing.

The aristocracy was also dissatisfied for other reasons. Pertinax also issued a decree relegating senators who had only received a nominal praetorship from Commodus to a lower class than those who held the office of praetor in earnest, removing the poor senators and equestrians from their estates. Some politicians had their life plans derailed since the praetorship was a prerequisite for advancement to provincial and consular positions. So, as Julius Capitolinus puts it, Pertinax “aroused in many a great hatred of himself.”

The emperor faced widespread resentment from both courtiers and the general populace. This animosity stemmed from reduced court expenditures, the seizure of assets from numerous freedmen of the empire, and the expectation of personnel adjustments usually accompanying a turbulent change in leadership. Rumors circulated that these changes were planned to coincide with Rome’s foundation day on April 21, 193.

According to some accounts, the individuals who had been administering the emperor’s affairs since Commodus’ reign had plotted Pertinax’s assassination in the baths days before the event, and numerous courtiers were actively urging the Praetorians to rise against the new leadership. After leaving his servants to his children, who all resided in different parts of the Palatine Palace, Publius Helvius found himself in a very unfriendly setting.

But Pertinax’s issues were mostly military in nature. The legions held all the power in the provinces, even though the emperor wanted to depend on the senate. From January to March 193, all of these military units remained subservient to the emperor; they included Decimus Clodius Albinus (in Britain), the Septimius brothers, Lucius Severus and Publius Geta (in Pannonia and Moesia), and Gaius Pescennius Niger (in Syria).

However, the Praetorians, who had a positive recollection of Commodus, were Publius’ major allies in the capital, and the new emperor was only acknowledged because there were no other choices. The Guard rapidly stopped supporting Pertinax for a number of reasons.

Due to a shortage of funds in the Treasury, he could only pay (donativum) six thousand sesterces per person instead of twelve thousand. On the first day of the new reign, the Praetorians were infuriated by the destruction of Commodus’ memory (Damnatio Memoriae), which included the destruction of statues, the removal of inscriptions, and the renaming of months in the calendar. Last but not least, the guards were reluctant to institute rigorous discipline, and Publius had already studied this topic in depth.

Therefore, the first effort to depose Pertinax occurred on January 3, 193. The Praetorian Guard chose to declare senator Triarius Maternus Lascivius as emperor, but Lascivius fled to the Palatine Palace and subsequently the city of Rome because he was afraid of the Praetorians. The next attempt was linked to Quintus Aemilius Laetus, a prefect of the Praetorian appointed by Commodus, who plotted his assassination and kept his position under the new emperor because he realized that Pertinax did not want to be in his sphere of influence. They found out about Laetus’ plot.

Pertinax declined to kill Sosius Falco, but many other conspirators, including the Praetorians who were caught for denouncing a slave, were condemned to death. The prefect himself was spared, and he even preserved his job as prefect.

Death of Pertinax

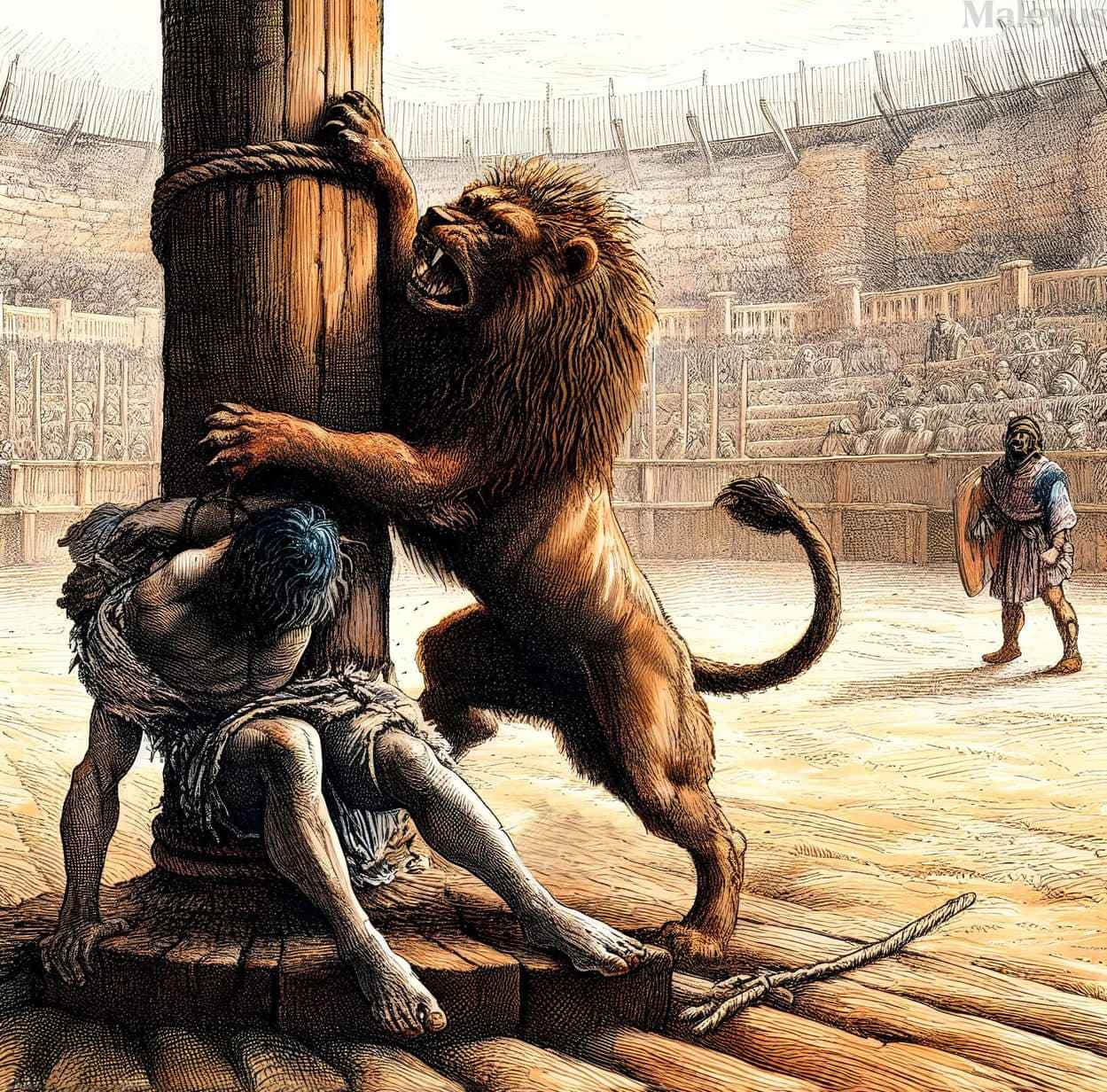

On March 28, 193, the situation in Rome became more serious. Titus Flavius Sulpicianus, Pertinax’s father-in-law and the newly appointed prefect of Rome, was sent to the Praetorian barracks to quell the disturbance there. Meanwhile, a squad of two hundred or three hundred guardsmen launched an assault on the royal palace. Publius dispatched Quintus Aemilius Laetus, who was still prefect of the Praetorian, to meet them for discussions, but Laetus did not comply and instead returned home (others believe Laetus was the true instigator of the insurrection).

Pertinax’s assassination led to a period of chaos known as the “Year of the Five Emperors,” during which several individuals briefly held the title of Roman Emperor in quick succession. This period marked the beginning of the Crisis of the Third Century in Roman history.

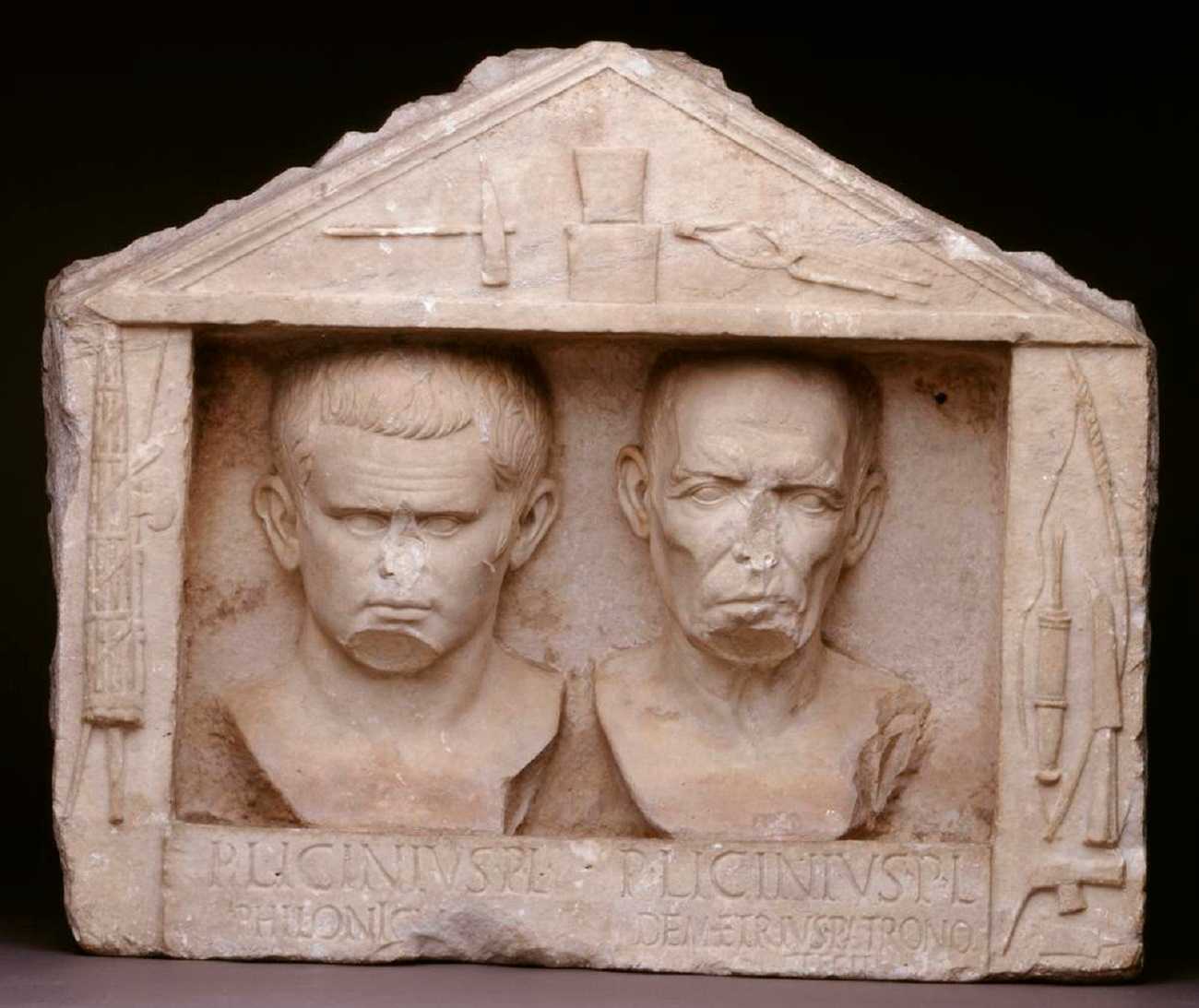

It was well known that Tausius, a member of the German tribe Tungri (Tungrian), was in charge of the insurgent Praetorians. All the guards who showed up at the palace could be part of a select cavalry unit made up of barbarians (equites singulares), leading researchers to conclude that the emperor could use other military units against them, presumably preserving loyalty, such as the palace guard or cavalry recruited from the Romans (equites praetoriani).

Tausius, the Roman soldier who killed the emperor Pertinax, was a Tungrian.

Instead, Pertinax went out to the rebels with the court administrator, Eclectus, and sought to calm them down while maintaining his dignity. Tausius thwarted this attempt and wounded the Emperor in the chest with a spear. As the others swarmed in to finish him off, Pertinax buried his face in his toga. The emperor’s severed head was then paraded through the streets of Rome, marking the end of his brief 86-day rule.

When his successor, Marcus Didius Julianus, arrived at the Palatine Palace, Pertinax’s corpse was already there. While the Roman historian Dio Cassius claims that Julian handled the body with scant care and had a feast while it was still in the palace, Julius Capitolinus claims that the latter ordered Publius to be buried at that time with all possible honors. Dio Cassius’ hostile attitude toward Julian suggests his account may not be accurate.

Didius Julianus became the new Roman Emperor after Pertinax’s death, although his reign was brief and fraught with controversy. This resulted in Septimius Severus becoming emperor and establishing his own dynasty.

References

- Historia Augusta, Life of Pertinax, English translation at Lacus Curtius

- Herodian, History of the Roman Empire, English translation at Lacus Curtius

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book 74, English translation at The Tertullian Project

- Aurelius Victor, “Epitome de Caesaribus”, English translation at De Imperatoribus Romanis