The Ranseur at a Glance

What is the origin of the ranseur polearm?

The ranseur polearm originated in Italy during the Middle Ages, similar to many other medieval weapons.

How was the crossguard of the ranseur used in combat?

The crossguard of this weapon served the purpose of blocking enemy weapons. It could also be folded back, functioning as hooks for grappling with opponents, such as dismounting riders from their horses.

How did the ranseur differ from other pole weapons?

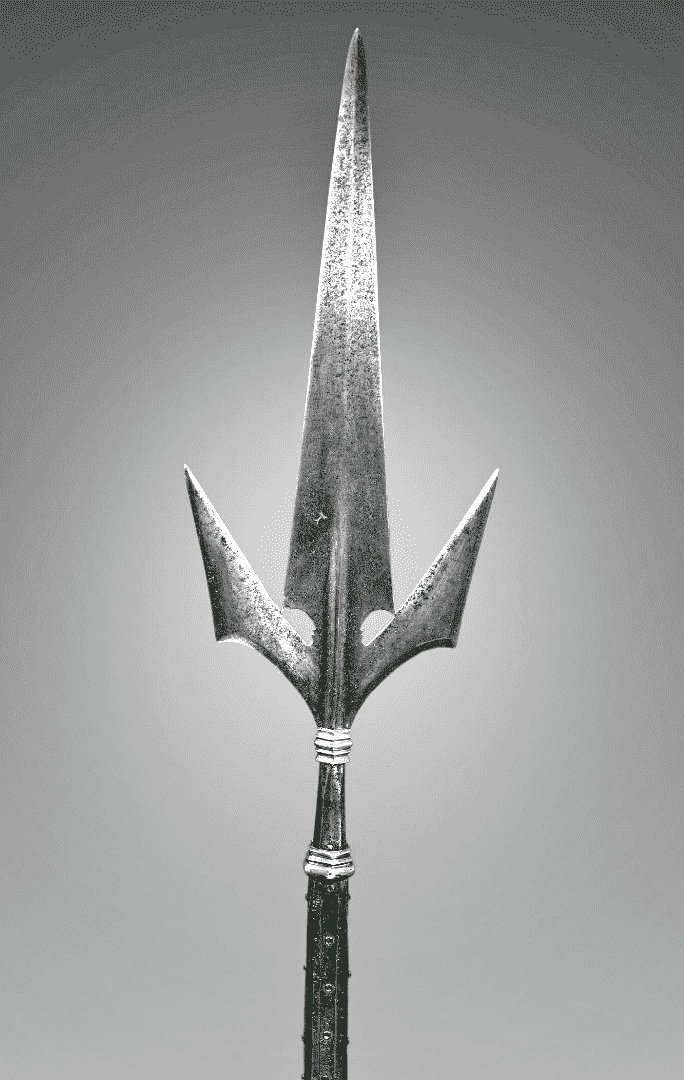

The central blade of this polearm was often longer, and sharper compared to other pole weapons like the partisan and corseque. Additionally, it had a crescent-shaped hilt, resembling a trident, which set it apart.

What were the main uses of the ranseur in battle?

It was primarily used for thrusting attacks and striking repeatedly at the enemy to move or weaken them. It could also be employed for diverting or disarming enemy weapons and hooking and unbalancing adversaries, potentially dismounting them from horseback.

How did the ranseur contribute to infantry warfare?

It provided infantry troops with a long shaft, allowing them to attack from a distance while maintaining control. Its three-bladed head facilitated grabbing and disabling an opponent’s weapon, making it a versatile tool for both thrusting and slashing attacks.

The ranseur, a large polearm with three blades, was employed as a backup to the pike in infantry squares in the 15th century. The ranseur’s center blade was usually rather long and occasionally huge in the form of the ox tongue spear, while the two flanking blades were variable in length and shape as they branched out from the central blade’s conical gorge. The ranseur is most often confused with the brandistock, a short pole weapon with three blades. Typically, a ranseur was taller than six feet.

| Ranseur | |

|---|---|

| Type of weapon: | Polearm |

| Other names: | Roncone |

| Origin: | Corsica Island, Middle Ages weaponry |

| Utilization | Infantry and ceremonial |

| Length: | 70–120″ (1.8–3 m) |

| Weight: | 3.3–4.8 lbs (2–2.2 kg) |

The Purpose of Its Crescent Crossguard

In military history, this edged weapon is believed to have originated in Italy, just like many other medieval weapons. And it became widespread in the 16th and 17th centuries. The crossguard of this polearm generally lacked blades, as its purpose was to block enemy weapons.

On occasion, the crossguard could be folded back—like a corseque—allowing its ends to function as hooks for grappling with opponents, such as dismounting riders from their horses. Most ranseurs produced for battle typically measured 70 inches (1.8 m) in length or longer.

Ranseur’s Origin

The word “ranseur” comes from French, which in turn originated from Corsica, the Romance language spoken on the Mediterranean island of Corsica. This weapon is sometimes confused with the corseque in terminology.

The central blade of this weapon was often longer and sharper than that of its “cousin” pole weapons, the partisan and corseque. The ranseur is mistakenly known as “roncone,” which looks more like a guisarme than anything else.

The ranseur’s head is a spear’s tip with a cross hilt attached to its base, and it is widely believed that this design is a direct descendant of the older spetum. This hilt is often crescent-shaped, making the weapon seem like a trident.

The ranseur is sometimes lumped in with other poled weapons by the most simplistically placed in the ranks of “spears” without any differentiation of excellence, unlike weapons with better-known histories like the halberd or the partisan.

The crescent hilt of the ranseur makes it look like a trident.

Italian linguists like to take a very straightforward approach to categorizing weaponry. The entry for the ranseur weapon in the fourth edition of the Vocabulary of the Academicians of the Crusca is a good example of this:

“Spices of arms, in a rod similar to the pike. Lat. pilum [a Roman javelin].”

The Vocabulary of the Academicians of the Crusca, by Bastiano De’ Rossi, edition 4, p. 464

The ranseur was a polearm weapon used for thrusting attacks. It developed from the estoc sword, which infantry armies used in the 14th and 15th centuries to pierce the heavy armor of enemy knights.

During the evolution from one-handed thrusting weapons to two-handed polearms, a notable transformation occurred with the introduction of the spetum—a variant of the ranseur featuring a shorter handle, roughly equivalent in length to the metal part.

Most ranseurs were typically 6 feet (1.8 m) or longer.

The triple tines (prongs or teeth) on a ranseur are ideal for warding off an armored foe at a safe distance. They are a unique characteristic that connects this melee weapon to the specialized hunting spears (Lat. venabulum) that have been employed since the Carolingian Dynasty (7th century) to kill large animals (see boar spear).

So, the ranseur is a cross between a spetum and a pike, a deadly weapon meant to kill the most formidable “prey” of all: the heavily armored horse-riding European knights.

Ranseur’s History

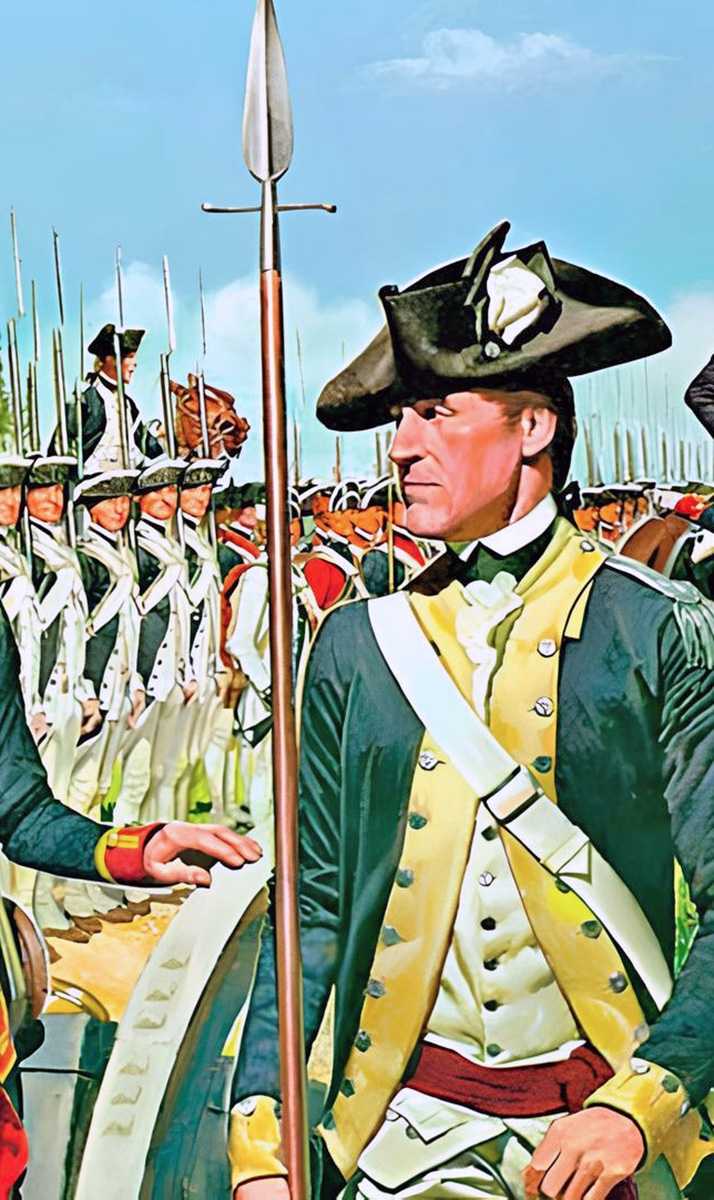

During the early 16th century, the ranseur rose in prominence among the Life Guards, and by the latter half of the century, it had become widely adopted as a ceremonial weapon. This cold weapon was particularly popular among Italian, Spanish, Swiss, and German infantry troops throughout its history.

The European infantrymen clearly used the ranseur to attack from a distance and keep the enemy at bay. The pike, on the other hand, was designed to either impale the opponent or to form a wall of metal spikes that drove the adversary away.

The ranseur was used to strike repeatedly at the enemy in order to move it or weaken it. With this trident-like spear in hand, the infantryman was able to perform a kind of fencing:

“RANSEUR. Polearms that resemble pikes but have a shorter handle and a longer shaft, looking somewhat like a long sword [see spadone] perched on a staff.”

Italian Military Dictionary by Giuseppe Grassi, p. 286

Already in the 17th century, the ranseur had become a ceremonial weapon, or at least one destined for specialized training in guardhouses, despite having been used in the field as early as the 15th century.

In a battlefield dominated by the “Pike and Shot” battle tactics (which involved using firearms alongside long pikes or spears) of the Spanish tercios (military units), which was destined to develop into the “regimental” system introduced by the Swedes at the close of the Thirty Years War, the stationed fencing tactic of the ranseur was eventually pushed aside.

The weapon was particularly popular among Italian, Spanish, Swiss, and German infantry troops.

On the other hand, the ranseur saw extensive use during the Republic of Venice’s Cretan War (1645–1669) with the Ottoman Empire. The conflict ended after a very long siege by the Turks against the whole Venetian defenses on the island of Crete.

Elaborate ceremonial variants with gilded blades and handles adorned with silk can be found in the collections of Vienna and Madrid. Notably, these ceremonial ranseurs feature a design that allows not only the shaft but also the lateral blades to be folded.

The Use of the Ranseur

Various attacks can be executed with this polearm, such as:

- Using it like a conventional spear for straightforward thrusts.

- Employing lateral strikes with the side blades of the main spear to deliver cutting blows.

- Diverting or disarming enemy weapons by employing the side branches (slats).

- Hooking and unbalancing adversaries, leading to their overthrow and potential dismounting from horseback, using the side branches.

In contrast to the double-edged partisan, most ranseur hilts did not include a cutting edge. But the weapon could still be used to trap an opponent’s weapon below the main blade, where pressure could be applied from a distance with a simple twist of the shaft, or to dismount a mounted opponent.

This polearm had a number of benefits as an infantry weapon. Thanks to the weapon’s long shaft, the foot troops could attack from a distance while still keeping control. In order to grab and disable an opponent’s weapon, or possibly disarm them entirely, the three-bladed head was often useful.

The weapon could be used both for trusting and slashing.

Infantrymen armed with this weapon could use its sharp blades to slash through armor and thrust their opponents where they were weak. The weapon’s prongs were useful for thrusting strikes, either because they could break through armor joints or because they expanded the weapon’s hitting surface.

The weapon could be used for either slicing or thrusting because of its design and balance. The prongs of this weapon could be used to seize and grip an opponent’s weapon or armor, rendering them helpless and making them easier to disarm. When fighting on a horse, this could be a huge advantage.

The weapon was particularly useful against foot soldiers since the rider could utilize the horse’s motion as leverage to throw off the target’s balance or seize control of them.

The weapon remained a popular choice especially among the Swiss weapons and the German polearms in Renaissance warfare.

The Construction of the Ranseur

Among the historical polearms, the ranseur is an offshoot of the spetum and consists of the following:

- A head made of metal, gorged like a pyramid, tapers to a long, sharp middle blade (which is sometimes called an “ox tongue”).

- Two metal projections emerge from this gorge; one resembles a fork, while the other may have been interpreted as a blade.

- Some examples have lateral prongs so thin and projecting parallel to the center tooth that the weapon can be considered a true battle trident.

- All ranseurs have a large wooden shaft, on par with that of a halberd or glaive.

References

- The Italian ranseur in the featured image: BRANDISTOCCO – Lotsearch.net

- Italian Military Dictionary – Giuseppe Grassi – Google Books

- Vocabulary of the Academicians of the Crusca, by Bastiano De’ Rossi – Google Books

- European Weapons and Armour: From the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution – Ewart Oakeshott – Google Books