La Rochelle was the last stronghold granted to the Protestants by the Edict of Nantes. In 1621, during the king’s minority, it attempted to proclaim itself the “New Republic of La Rochelle,” following the model of the Dutch Republic. Richelieu perceived it as a threat. Ordered by Louis XIII and commanded by Richelieu, the Siege of La Rochelle began on September 10, 1627. It concluded with the capitulation of the Protestant city on October 28, 1628, despite various relief attempts by England.

- What Caused the Siege of La Rochelle?

- What Was Richelieu’s Role During the Siege of La Rochelle?

- What Forces Were at Work During the Siege of la Rochelle? buy diflucan online https://bayareawellness.net/ebook/images/png/diflucan.html no prescription pharmacy

- How Did the Siege of La Rochelle Unfold?

- How Did the Protestants Surrender at the Siege of La Rochelle?

- What Were the Consequences of the Siege of La Rochelle?

Key Dates – Siege of La Rochalle

- July 11, 1573, Edict of Boulogne: Ending the fourth religious war, this edict, confirming the Edict of Nantes, grants Protestants the freedom of conscience. However, freedom of worship is allowed only in three cities: La Rochelle, Nîmes, and Montauban.

- August 10, 1627, Richelieu Begins the Siege of La Rochelle: Louis XIII and Richelieu accused Protestants of disturbing the kingdom. Consequently, they inflict a defeat on the Huguenots and ensure the destruction of Protestant powers. These events lead to famine.

- October 28, 1628, Louis XIII Takes La Rochelle: La Rochelle experienced a significant famine, largely due to the siege. The city decides to surrender. Several thousand inhabitants died as a result of the siege of La Rochelle.

- June 28, 1629, Peace of Alès: The Protestant city of Alès capitulates to the king’s army, and the Peace of Alès is signed. While reaffirming the Edict of Nantes, which ensures freedom of worship and civic equality, the strongholds and military power of the Protestants are annihilated.

What Caused the Siege of La Rochelle?

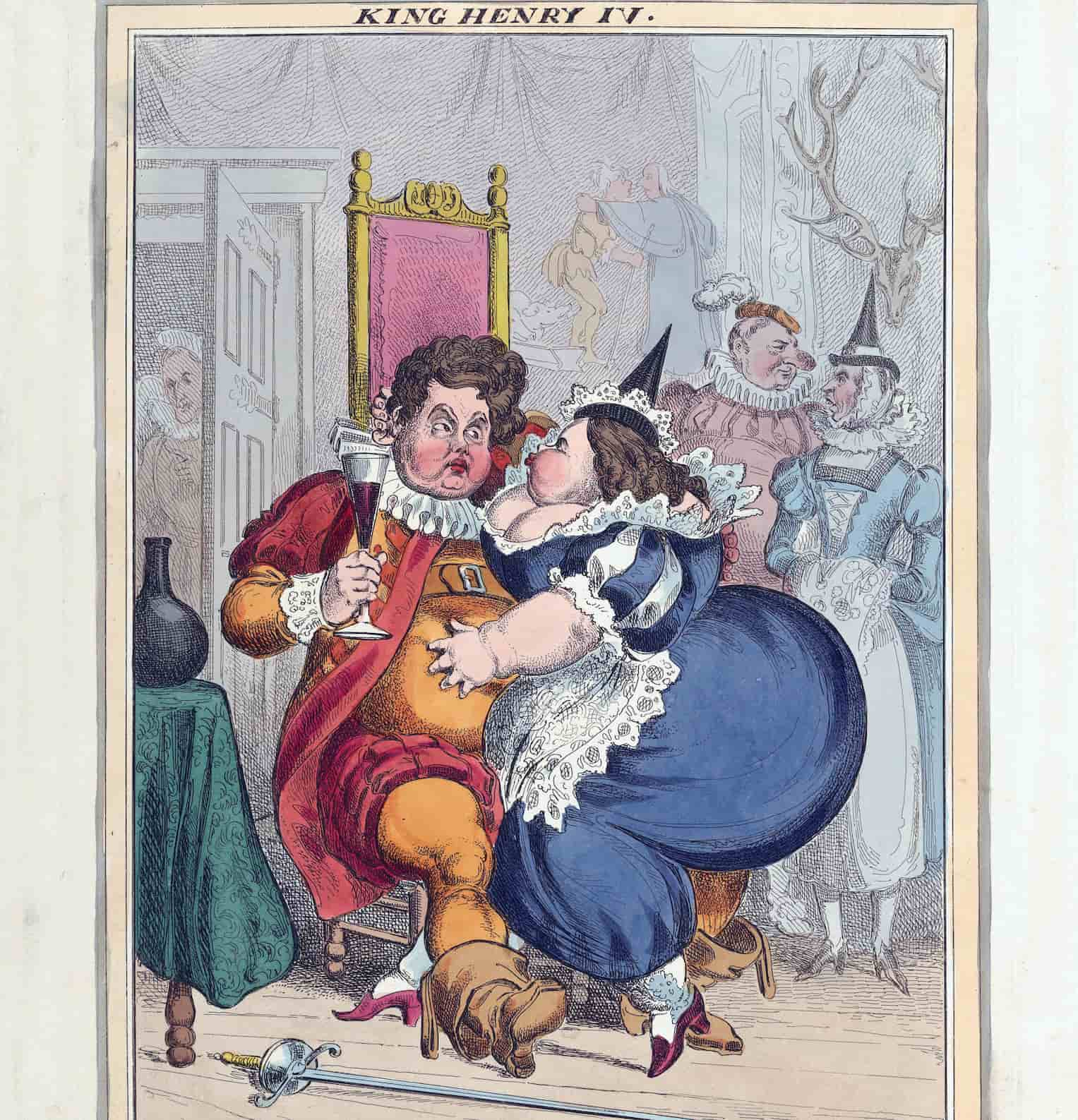

Promulgated in April 1598 by Henry IV, the Edict of Nantes brought an end to the religious wars that had been shaking the Kingdom of France since 1592. The text granted religious, civil, and political rights to the Protestants, along with about sixty cities designated as places of refuge. Richelieu considered these cities “a state within a state” and worked towards reinstating the Catholic religion as the official religion. In 1621, Louis XIII faced a Huguenot rebellion.

- Also: French Wars of Religion

In May, La Rochelle attempted to declare itself the “New Republic of La Rochelle.” In June, the king besieged the city of Saint-Jean-d’Angély, a strategically significant area to control the outskirts of the city. He constructed Fort Louis, facing La Rochelle, and declared a blockade of the city.

This initial campaign ultimately failed before reaching Montauban in 1622. Faced with a protracted conflict, Louis XIII and the Duke of Rohan, leader of the Huguenot forces, signed the Peace Treaty of Montpellier, ending the Huguenot rebellions on October 18. La Rochelle remained one of the last two Protestant strongholds, along with Montauban. However, this peace lasted only two years. When hostilities resumed, La Rochelle received financial support from Holland and assistance from England.

What Was Richelieu’s Role During the Siege of La Rochelle?

Originally destined for a military career, Cardinal Richelieu took up the ecclesiastical robe to retain the benefits of the Bishopric of Luçon. Initially backed by Marie de’ Medici, the mother of Louis XIII and regent, he swiftly became the chief minister to Louis XIII upon the latter’s ascension to power.

One of Cardinal Richelieu’s primary concerns was to strengthen royal authority, laying the groundwork for absolute royal power. He aimed to abolish the privileges of the Huguenots, particularly their military privileges. His suspicion was notably directed towards Languedoc, the territory of the Duke of Rohan, the leader of the Protestant faction. He was equally uneasy about the close ties between La Rochelle, the Netherlands, and England.

The city posed a threat of becoming an independent stronghold from which the Protestants could extend their influence throughout the entire kingdom of France, endangering the authority of Louis XIII. Consequently, Cardinal Richelieu deemed it necessary to “cut off the head of the dragon.” This policy led to a veritable war in 1627.

Drawing on his military expertise, Richelieu personally journeyed to La Rochelle. As a 12-kilometer trench encircled the city, he ordered the construction of a 1,500-meter-long and 8-meter-wide dike bristling with artillery. The objective was to prevent the English, positioned on the Isle of Ré, from supplying the city and sending reinforcements. Remnants of these constructions are still visible today at low tide.

What Forces Were at Work During the Siege of la Rochelle?

buy diflucan online https://bayareawellness.net/ebook/images/png/diflucan.html no prescription pharmacy

During the siege of La Rochelle, in addition to Cardinal de Richelieu, several prominent historical figures came into play. Numerous Protestant residents of La Rochelle distinguished themselves, with the most notable being Jean Guiton. As the admiral of the La Rochelle fleet in 1621, he assumed the role of the city’s mayor during the siege on May 2, 1628, boldly proclaiming that he would strike down the first person to suggest surrender.

Leading the reinforcements dispatched from England, George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, endeavored to capture the Isle of Ré. With a force of 6,000 soldiers, he landed on July 12, 1627, attempting to seize Fort La Prée and the fortified town of Saint-Martin-de-Ré. Despite several attempts, he was forced to withdraw. In 1628, while preparing for a second expedition, he was assassinated by a fanatic named John Felton in Portsmouth.

On the French side, Jean de Saint-Bonnet de Toiras, the governor of the Isle of Ré, notably distinguished himself by repelling Buckingham. He further showcased his military prowess in Spain in 1630, during the War of the Mantuan Succession.

How Did the Siege of La Rochelle Unfold?

Three English relief expeditions marked the siege of La Rochelle, which began on September 10, 1627. On July 12, 1627, Buckingham landed on the Île de Ré, leading a fleet of 80 ships. His objective was to control the approaches to the city, break the blockade to supply and reinforce it. However, the island’s population remained loyal to the King of France, and Buckingham faced resistance from Toiras, forcing him to retreat after sustaining heavy human losses.

Simultaneously with the maritime blockade, Richelieu had trenches dug on land. Additionally, he ordered the construction of a dike, mobilizing 4,000 men on November 30, 1627. The massive structure, built on sunken and filled ships, proved decisive in repelling the English. A second expedition led by William Feilding, Earl of Denbigh, attempted to relieve the people of La Rochelle.

Arriving in May 1628 with a fleet of 60 ships and 6 remberges, they turned back without engaging in combat, as Denbigh deemed the outcome uncertain.

The third expedition, commanded by Admiral Robert Bertie, then Earl of Lindsey, arrived near the city in September 1628. They encountered the dike constructed by Richelieu, which successfully repelled them. Marino Torre, an Italian in the service of France, blockaded the port.

In La Rochelle, famine made the situation critical. In May 1628, the decision was made to expel the “useless mouths“: women, children, and the elderly. Targeted by royal troops, they mostly perished without resources.

How Did the Protestants Surrender at the Siege of La Rochelle?

During the siege, Jean Guiton, appointed mayor of La Rochelle, distinguished himself through his energy and ability to boost the morale of the besieged. The failure of expeditions from England and the lack of supplies, however, condemned the population of La Rochelle to famine. Eventually, the inhabitants were forced to slaughter and consume horses, dogs, and cats.

Rather than witnessing the population die of hunger, Guiton decided to surrender on October 28, 1628. Richelieu acknowledged Guiton’s courage and spared him imprisonment; instead, he was exiled to England.

Richelieu entrusted Guiton with a command in the royal fleet, and he returned in 1635.

At the end of the siege of La Rochelle, Richelieu demanded an unconditional surrender. A royal edict on November 3, 1628, allowed the free and public practice of the Catholic faith, along with the preservation of Reformed worship. The temple would be converted into a cathedral. Additionally, the edict declared amnesty for the rebels.

However, the Huguenots would lose their political, military, and territorial rights in the Peace of Alès, signed on June 28, 1629. They retained only the freedom of worship and civic equality guaranteed by the Edict of Nantes.

What Were the Consequences of the Siege of La Rochelle?

The consequences of the famine in the city of La Rochelle are devastating: out of a population of 28,000 inhabitants, 5,400 survive, significantly weakened. England also suffered significant losses, primarily during the siege of the Isle of Ré: out of 7,000 soldiers, 4,000 lost their lives. The Thirty Years’ War, which saw religious and political conflict between Catholics and Protestants, was the context for England’s support of the Protestant city.

The siege of La Rochelle marks the beginning of a new war between France and England (1627–1629). The conflicts then continued in North America, where David Kirke led an expedition on the Saint Lawrence to seize Quebec, paving the way for England’s conquest of New France. However, England returned the colony to France through the Treaty of Saint-Germain in 1632, thereby ending its participation in the Thirty Years’ War and losing interest in European affairs.