Spadone at a Glance

What is a spadone and what other names is it known by?

The spadone is a type of two-handed sword that originated in Italy during the Renaissance. It is also known as the zweihander in Germany, the greatsword in England, the claymore in Scotland, and the montante in Spain and Portugal.

Who were some famous users of the spadone?

One of the most famous spadone users was Pier Gerlofs Donia, a Frisian rebel leader and pirate of the early 16th century who was renowned for his immense strength and effectiveness as a swordsman. Another notable group of spadone users were the mercenary lansquenets who protected the Knights Hospitaller during the 1522 siege of Rhodes.

How was the spadone used in battle?

The spadone was versatile enough to be used as a cutting tool, an impact weapon, or even as a polearm, depending on the situation. It could be employed as a slashing weapon against unarmored foes or as an impact weapon against knights in armor. The large cross guard and parrying hook allowed for a variety of grips and could be used to direct the sharp tip of the sword with pinpoint accuracy to areas of the body not covered by armor.

What is the historical significance of the spadone?

The spadone was one of the most powerful edged weapons ever produced in history and was used in many important conflicts during the Renaissance, including the Swabian War, Italian Wars, and German Peasants’ War. It was also a symbol of status and power, often used as a ceremonial bearing sword. The cultural influence and romanticization of swordsmanship during the Romanticism period contributed significantly to the overestimation of the abilities of sword-wielding knights.

How did the spadone compare to other swords of its time?

The spadone was one of the largest and heaviest swords of its time, typically weighing 5.7 lbs (2.6 kg) and measuring up to 79 inches (200 cm) in length. It was more commonly referred to as a zweihander than a spadone in history, although they were essentially the same weapon. Its size and weight allowed for a variety of uses, including as a cutting tool, an impact weapon, and even as a polearm.

During the Renaissance, Italy and the countries surrounding the Holy Roman Empire—essentially Germany and Switzerland—produced a new style of two-handed sword known as the spadone in Italy, the zweihander in Germany, the greatsword in England, the claymore in Scotland, and the montante in Spain and Portugal. Spadone means something like “great sword” in Italian, similar to zweihander, which means “two handed,” and montante means “very large sword.” This cold weapon was one of the most powerful edged weapons ever produced in history.

Spadone was used between the 15th and 17th centuries, most notably in the Swabian War (1499), Italian Wars (1494–1559), and German Peasants’ War (1524–1525). A typical spadone weighed 5.7 lbs (2.6 kg) and had a length of up to 79 inches (200 cm).

Note: For a reason, this sword is more commonly referred to as a zweihander than a spadone in history. But they were pretty much the same weapon.

The Accounts of the Usage of Spadone

We have accounts of skilled swordsmen who wielded the deadly spadone in Renaissance and modern Europe, so while it is true that the romanticization of swordsmanship during the Romanticism period contributed significantly to the overestimation of the abilities of sword-wielding knights, this fact cannot be ignored. Therefore, we need to take into account not just the cultural influences but also the historical facts that have shaped our understanding of swordplay.

1. The most famous spadone users include the Frisian rebel leader and pirate Pier Gerlofs Donia (1480–1520) of the early 16th-century anti-Habsburg rebellion. Donia was legendary for his immense strength and renowned for his ability and effectiveness as a swordsman. His greatsword or spadone stroke was so powerful that it was said he could behead many people at once.

Since 2008, a zweihander (the local name of the sword) with measurements of 84 inches (213 cm) in length and 14.5 lbs (6.6 kg) in weight has been on display at the Leeuwarden Museum.

However, other accounts suggest that the scholar Ewart Oakeshott (1916–2002) was probably correct in his assessment that the spadone was most often employed in duels and defensive situations rather than the battlefield.

2. The Knights Hospitaller—outnumbered by Suleiman the Magnificent’s army during the 1522 siege of Rhodes (100,000 Turks to 7,000 Christians)—relied on mercenary lansquenets (an archaic variant of landsknecht) equipped with spadones to protect the city’s fortifications. Despite losing twenty thousand men in the attack on the Christian stronghold, the Turkish sultan decided to negotiate a surrender in the enemy’s favor.

The French naval officer Prégeant de Bidaux—known for his brutality—stood out throughout this fighting. His spadone could slash through “half a man clean,” and his Herculean frame made him a feared pirate for the Hospitallers. The man was known for his “love for the war and hate for the Turks.”

3. Benedetto Varchi mentions a particular captain Goro in his book Storia Fiorentina. He was a mercenary for the Florentine government who used his two-handed spadone to split two of the Volterran (a town in Italy) rebels who had stormed the town hall.

4. In his autobiography, Benvenuto Cellini, a Florentine bronzesmith and artist, writes of an attempt on his life by French bandits to steal from him when he was in Paris. For his part, he describes using a two-handed spadone in self-defense situations.

The spadone could be used as a cutting tool, an impact weapon, or even as a polearm, depending on the situation. This was because the blade could be extended quite a ways, the weight was distributed, and the hands were well protected because of the large cross guard and the parrying hook, which allowed for a variety of grips.

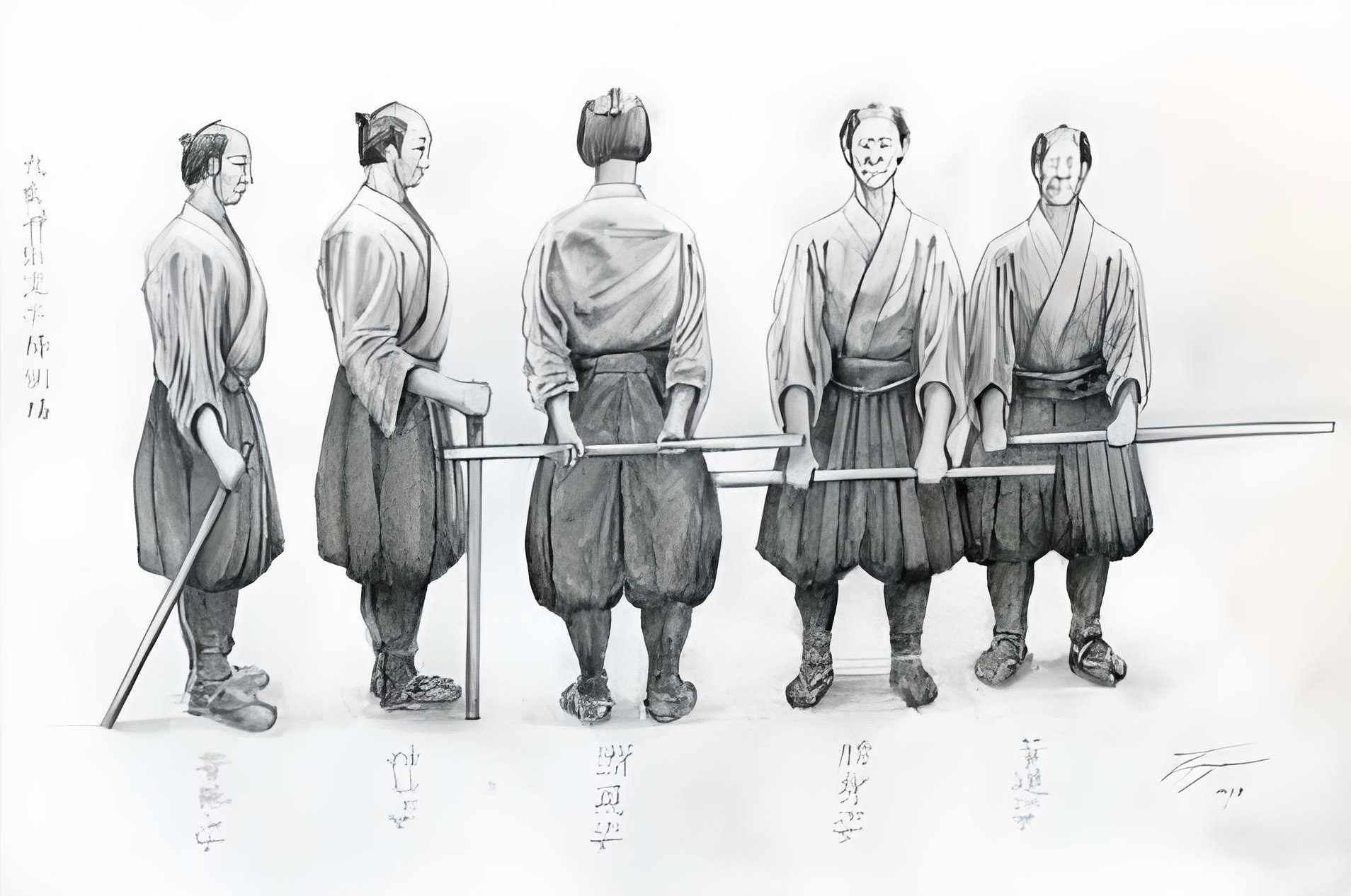

The lansquenet infantry was often deployed in the shape of human walls, each member keeping a hand on the ricasso of his spadone. This allowed the weapon to be employed in the same manner as a lance, both in halting aggressive cavalry assaults by unseating the knights and in close-quarters combat.

The spadone was versatile enough to be employed as a slashing weapon against unarmored foes or as an impact weapon against downed knights in armor (the misericorde dagger served a similar purpose).

Because of the “second grip” with the “parrying hook” and the blade’s long reach, the sharp tip of the spadone could be directed with pinpoint accuracy to the areas of the body that were not covered by chain mail or plate armor—again, similar to the misericorde.

History of Spadone

During the Renaissance, the spadone (or zweihander) rose to fame as the signature weapon of the first Swiss mercenaries and the Landsknechts, having reached its final form in the countries that surrounded the Holy Roman Empire (founded in Italy, Germany, and Switzerland) in the 15th century. To combat the Swiss, Emperor Maximilian I of the Habsburgs founded the Landsknechts and equipped them with spadones.

As a two-handed sword modified for use in foot duels between medieval knights, the spadone likely originated in Spain (it was known as “espadon” in later times, probably the origin of “spadone” or the other way around). However, the montante or espadon did not grow to the gigantic proportions of their German and Italian counterparts.

During the late Middle Ages, knights would engage in foot duels using this variant of the two-handed sword known as the spadone or zweihander (there is still an ongoing debate on the original name of this weapon). The style of combat changed dramatically with the spadone during the Renaissance.

Heavy and versatile, the spadone was designed for tremendous cutting assaults and soon became standard equipment for the largest infantrymen and the best swordsmen. The soldiers who wielded spadones were stationed at the front of the formation and tasked with clearing the field of enemy pikes with violent strikes so that the rest of their mates could properly step into the enemy field.

When compared to the two-handed sword traditionally used in the swordsman-on-swordsman duel, the spadone was also repurposed as a “pike cutter.” Whether facing an unarmed foe or one armed with a sword, the spadone proved effective as a surrogate for a polearm weapon.

But unlike polearms, its blade swung and vibrated around a lot due to its length. That’s why the weapon masters covered the ricasso (the small, unsharpened part of the blade above the guard) with leather to grip the blade during an attack.

The swordsman would clutch the hilt and ricasso of the spadone, then thrust it forward in a lunge that resembled a spear thrust more than a sword thrust.

In Germany, “Doppelsöldner” was a designation given to the Landsknechte soldiers who were proficient with spadones/zweihanders and also arquebuses. They were paid twice as much as their pikemen or halberdier counterparts. The literal translation of “doppelsöldner” is “double pay.

Even before the start of the 16th century, fewer and fewer soldiers were using spadones in combat. The Doppelsöldner’s charge at the pikemen was now a senseless and unnecessary mass suicide due to the growing number of arquebusiers within the ranks of European armies. The book titled The Pike and Shot Tactics 1590–1660 explains this era.

The use of the spadone in duels continued far into the 17th century.

A Spadone’s Design

Traditional Italian fencing treatises stipulate that a spadone must be the same height as its wielder. For comparison, a traditional two-handed sword could be as short as the height of the fencer’s armpit.

The spadone’s hilt was enormous. The grip—often covered in leather—was around 20 inches (50 cm) in length, or something along the lines of four palms. The cross guard with straight arms was of a similar length to that grip, completing the impressive size of the hilt.

The front hand of the swordsman served as a pivot against the handle, while the rear hand, positioned near the pommel, functioned as a lever. This strategic arrangement enabled the swordsman to execute powerful strikes with spadone rapidly and effectively.

While some spadone examples were lavishly decorated with expensive materials like ivory, this was not the norm. However, the spadone’s guard was characteristic of a katzbalger (a short Renaissance sword) in that it also featured two rings that extended outward from the cross guard.

The spadone, as it is used today, features a handle that can accommodate four palms and more, and is equipped with a large cross. This design is not intended for use in the same way as other weapons we have discussed. Rather, it is meant to be used alone, allowing its wielder to stand in the guise of a galleon among many galleys, resisting multiple swords or other weapons simultaneously.

1594, “Di Grassi, His True Arte of Defense” by Giacomo di Grassi.

To ensure that the spadone can be used for both defense and offense, it should be divided into two halves. Its length should be proportionate to that of a man, not too long nor too short. It must have sharp double edges and be lightweight so that the observer of this art can execute cutting and pointing blows with greater speed and ease. It is also important to have a good supply, as the hand is the main tool that operates according to nature and the rule of art.

Francesco Alfieri, a 17th-century Italian master of fencing.

In spadone, the tip of the ricasso (the unsharpened blade piece above the guard) was sometimes further covered by a second guard made of “parrying hooks” (parierhaken) about 2 inches (5 cm) in length, similar to those seen on the spetum or corseque pole weapons. Fencing “half-sword” techniques necessitated this parrying hook, and it served to protect the hand.

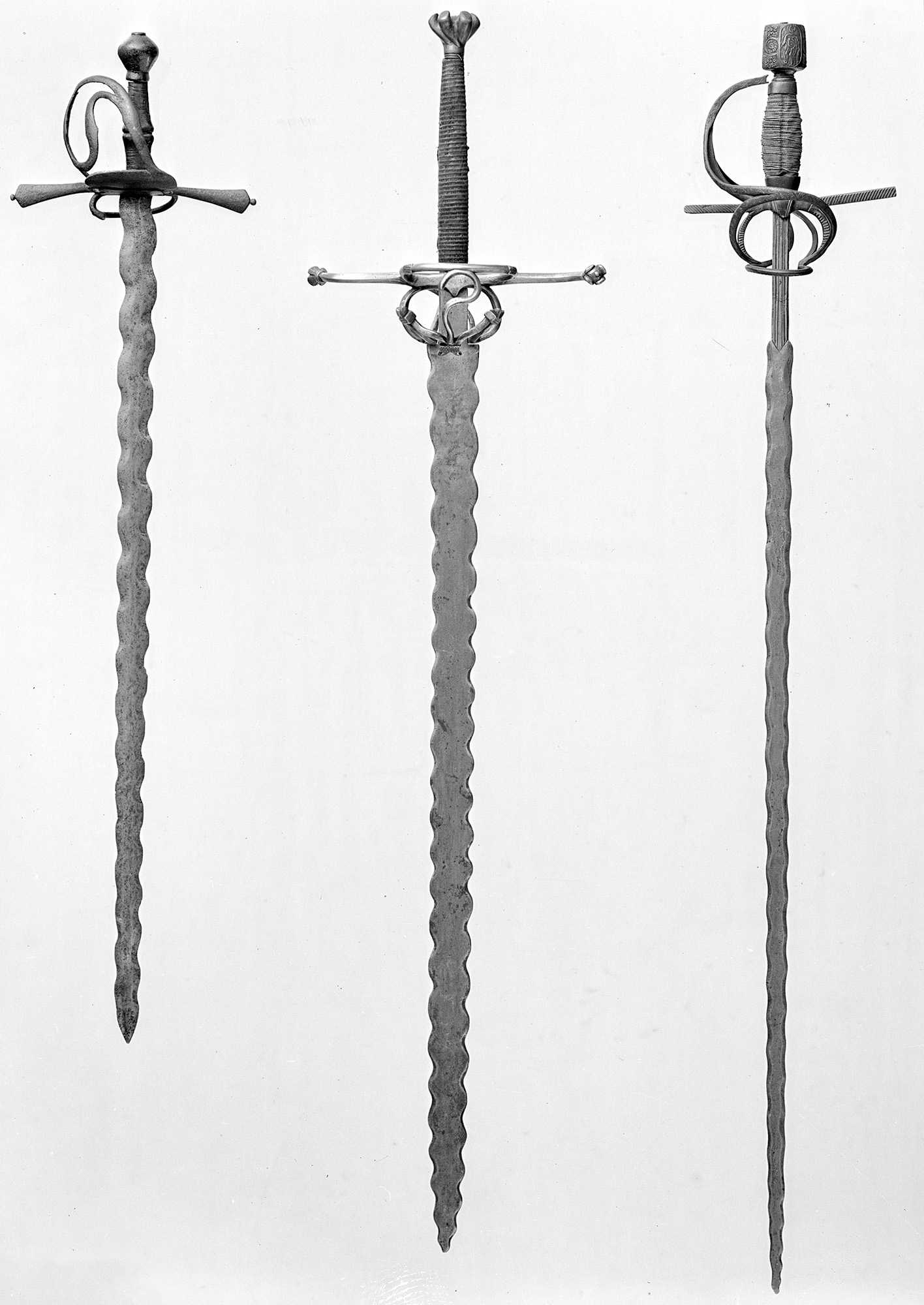

The spadone’s blade was often 40 inches (1 m) or more in length, and its ricasso was occasionally sheathed in leather. One or both sides of the blade could be wavy, like a flame-bladed sword. There is ongoing discussion over whether or not a wavy blade is really effective. The idea that it can help enhance the cutting blow at the point of contact is often disregarded, particularly when used against the shafts of pikes or halberds.

The theory that the wavy cutting edge was utilized to parry an opponent’s sword by unloading more force on the blade is more intriguing. The typology of the flame-bladed spada da lato (“side sword”), which became popular alongside the spadone as a dueling weapon, lends credence to this theory.

During the 16th century, European spadones came in a wide range of sizes, regardless of differences in design or technique. The Landeszeughaus Museum in Graz has a collection of preserved spadones, whose average dimensions are 67 inches (170 cm) in length and 7.7 lbs (3.5 kg) in weight.

The biggest example of spadone, however, is 78 inches (199 cm) long and weighs about 13 lbs (6 kg), still belonging to the category of functional, non-ceremonial weaponry. For comparison, the Spanish montante from the Mediterranean region is typically 59 inches (150 cm) long and weighs between 4.5 and 5.5 lbs (2 and 2.5 kg).

Spadones with completely wavy blades existed as well. The zweihanders of this type were purely ornamental, with a size and weight much larger than those of other spadones. Those zweihanders measured almost 79 inches (2 m) in length and 15 lbs (7 kg) in mass. Since their blades resembled the shape of a flame, they were also known as flamberge swords.

References

- Oakeshott, Ewart (2012), European Weapons and Armour: From the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution, Boydell Press, ISBN 0-85115-789-0.

- Caro, L. De (2020), Storia Dei Gran Maestri e Cavalieri Di Malta, Google Books.

- Roberts, Keith (2010), The Pike and Shot Tactics 1590–1660, Amazon.

- 1594, “Di Grassi, His True Arte of Defense” by Giacomo di Grassi.