Economist Jean Fourastié used the phrase “Trente Glorieuses” (the Glorious Thirty) to describe the prosperous years after the Liberation and continuing into the 1970s. France was in shambles by the time World War II ended. Cities had to be rebuilt and, as part of the Marshall Plan, the United States provided financial aid to help kickstart the country’s flagging economy. And these changes included heavy governmental intervention in the productive sector. This period was a veritable economic miracle for France. The period saw both a rise in GDP and a general improvement in living conditions in France.

France On Its Way to The Trente Glorieuses

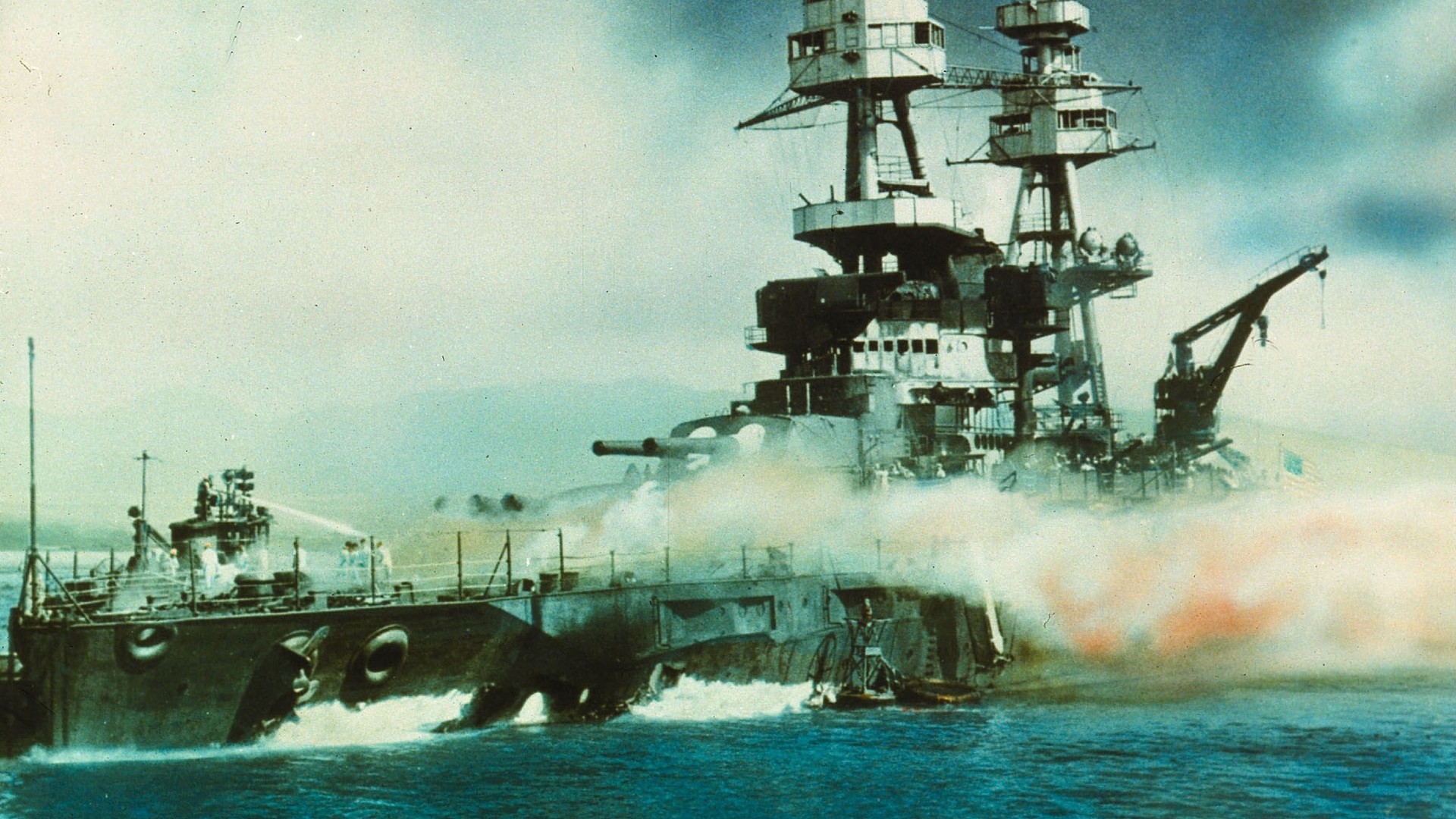

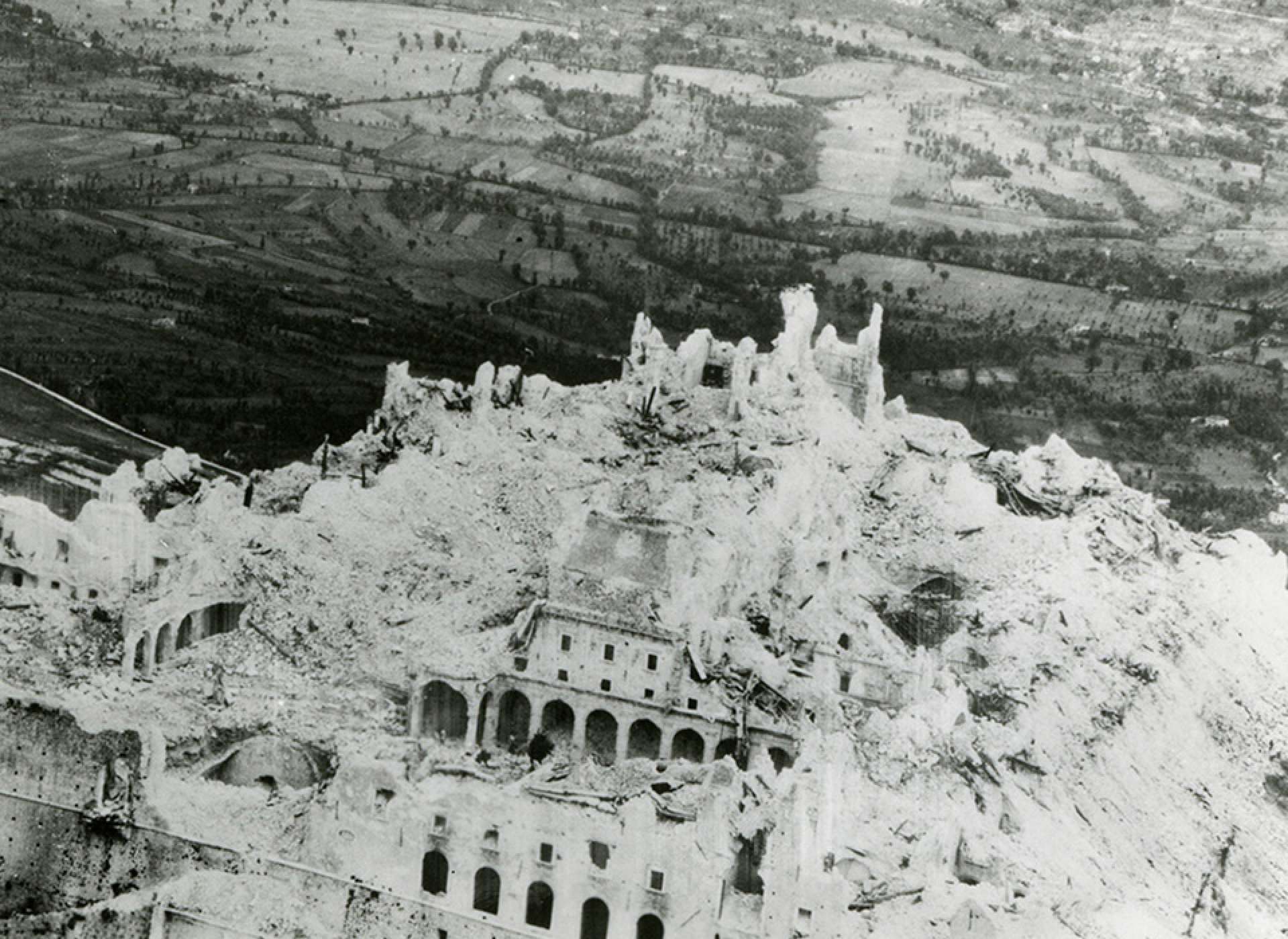

Defeated and ruined, France was unable to recover from World War II on its own. Approximately 600,000 people lost their lives and the country suffered heavy devastation. The railway network was essentially inoperable and the economy was wiped out. France was also extremely vulnerable due to its lack of financial reserves.

The economy was in a terrible state at the time of the Liberation. City after city laid in shambles. The war for the railroads had severely weakened the system. The majority of bridges were blown up, and communications were disrupted. The French manufacturing infrastructure was not immune to this catastrophe. Coal production, for instance, dropped from 67 million tons to 40 million tons. France had regressed by fifty years. It was no surprise that the underground economy and price inflation flourished under these conditions.

As a solution to this problem, one of the Liberation’s first key decisions was to raise wages. Each and every French citizen was asked to take part in the manufacturing war. There was talk of “rolling up their sleeves” and “soldiers of restoration” during this “third battle of France.” In addition to the difficulty of modernizing the country, the Liberation and Fourth Republic economies shared a common feature: the imposition of a strict form of economic dirigisme.

Therefore, in light of this persistent inflation, the State was compelled to step in and aid in the reconstruction and reform of the country. This was accomplished by utilizing the American Marshall Plan whose primary goal was to facilitate the rebuilding of Europe. Almost $13 billion was split among 13 European nations under this scheme. Despite being impacted by World War II, the Soviet Union turned down American help, setting the stage for the future Cold War.

Reforms for Progress

Two key developments that helped France were created as a result of the war’s end and the subsequent, extensive economic restructuring. The establishment of Social Security was the first. This was more than just a rearrangement of the furniture, even though the country wasn’t beginning from zero and there was genuine history here.

It was a radical new approach, focused on making society more equitable through planning for and implementing genuine risk protections. This reform, conceptualized by Pierre Laroque, was in direct response to the need for respect for human rights and equality. From that point on, workers had greater security against the hazards of their jobs, such as unemployment, illness, old age, and accidents. They were also eligible for family benefits. To further encourage employee participation in corporate affairs, businesses with more than fifty workers were permitted, under an ordinance passed on February 22, 1945, to establish committees.

Both of these measures were being taken at a time when the economy of the country had to be restored in an effort to foster more social unity. To bring about this transformation, there had to be a new type of government involvement in the economy.

What Tools Were Needed for This Transformation?

It became immediately apparent that a variety of changes had to be implemented using different methods in order to restart and rebuild the economy. New institutions were established in the country, whose goal was to track the economy’s development over time. The INSEE and the General Planning Commission were established in 1945 and 1946, respectively, to address this deficiency and to rebuild and modernize France.

Simultaneously, a spate of nationalizations provided the state with additional tools for involvement. The nationalization of the Renault factory was the most well-known instance of this type of economic intervention. This action was taken due to Louis Renault’s cooperation with the Nazis. After seizing control of the plants during the Liberation, the state established a new firm, the National Company of Renault Factories, which reported directly to the Minister of Industrial Production.

Power plants were also taken over by the government. Charbonnages de France, Electricité de France (EDF), and Gaz de France (GDF) were founded, and the political establishment gained control of many major banks (Crédit Lyonnais, Société générale).

Through governmental intervention, the economy was revitalized under the Fourth Republic. Thus, the stage was set for the “Trente Glorieuses,” as coined by Jean Fourastié.

A Period of Economic Prosperity

France lost a lot of money due to the Great Depression of the early 20th century and the two world wars (World War I, World War II and Vichy France) that followed it. France had an extended period of exceptional development from 1945 until the 1970s.

Prosperity is measured by gross national product (GNP), but global GNP per capita went from around $2,110 in 1950 to around $4,090 in 1970 (the Maddison Method). During these “Trente Glorieuses,” the country saw rapid industrialization. The consumer goods and transportation industries reaped the most benefits. In contrast, growth was more sluggish in the core sectors of iron and steel, textiles, and basic chemicals. Increased energy mobilization was a byproduct of this expansion. As a result of its low price and high energy content, oil was quickly becoming the world’s primary growth fuel.

The dramatic shift in the employment share across the economy’s three main sectors was another factor contributing to the country’s recent economic success. There was a decrease in demand for labor in the primary sector, while the secondary sector saw a rise in its workforce with negligible gains. However, the tertiary sector* and the number of “white collar” workers were also seeing rapid growth.

Towards a Consumer Society

France’s transition towards a modern consumer culture began with the “Trente Glorieuses” (Glorious Thirty). Many ideas and customs were adopted from the United States during this time. In the 1950s, the French started to stock up on consumer goods such as the first televisions, refrigerators, washing machines, and automobiles. These items became increasingly accessible to them, largely due to the proliferation of supermarkets.

During the 1950s and 1960s, consumption served not only to satisfy individual needs, but also as a way to make a social statement and elevate one’s standing in society. This period of affluence disrupted everyday life, as the introduction of domestic appliances also changed the structure of the family. For example, parents had more time for their children’s education, their own hobbies, and some women were able to enter the workforce.

There was a shift in household budgets as people moved into the modern era, with an increase in spending on items such as machinery, healthcare, and recreation.

The Reason for The Growth

The supply and demand dynamic was one of the main drivers of economic expansion during this time. There was a greater need for goods, which led to an increase in supply. Production methods such as Taylorism, Fordism, and assembly line work also contributed to this shift, as they allowed for the gradual replacement of skilled workers with specialized workers, resulting in cost savings. These factors allowed the country to increase output while decreasing costs. Additionally, the average time spent in school increased, with the number of high school graduates in 1970 being four times that of 1946.

The primary driver of economic expansion was the increase in consumer demand. As the number of buyers grew, so did consumption. There was also a steady increase in purchasing power. In 1948, it took almost 2,600 hours of work to purchase a Citroën 2CV, but by 1974, that number had dropped to 1,000 hours.

It is worth noting that this was also the era of full employment and a significant change in salaries, as workers were paid once a month instead of once a week, giving them more discretionary income to spend.

An Economic Boom That Did Not Benefit Everyone

During this time, the label “Third World” was coined to describe nations that were left out of the economic expansion. However, even within the nations driving the “Trente Glorieuses,” there were movements of rejection. In France, low wages contributed to uncertainty and left some people behind as the population increased, leading to the persistence of shantytowns until the early 1970s. In this period of abundance, a “fourth world” emerged.

Some observers questioned the expansion, as they opposed the idea of living according to the dictates of the market. The “subway, work, sleep” routine was rejected, leading to the emergence of left-leaning movements that offered an alternative to the consumerist system. These movements advocated for a return to rural living, such as on the Larzac plateau.

The End of the Trente Glorieuses (Glorious Thirty)

Contrary to the belief that the economy collapsed suddenly in response to the first oil shock, the first signs of a slowdown appeared at the beginning of the 1970s, and the energy crises of 1975 and 1979 further exacerbated the situation.

When compared to the economic and social climate at the end of the 1990s, the “Trente Glorieuses” stand out as the strongest period of growth France had ever experienced. This moniker successfully underlines the period’s almost mythological nature. Its rate of expansion over 30 years was higher than that of France from 1830 to 1914.

Bibliography:

- Jean Fourastié : “The Thirty Glorious or the invisible Revolution from 1946 to 1975”, 1979 and “The great Hope of xxe siècle”, 1949

- Dominique Lejeune, La France des Trente Glorieuses, 1945-1974, Armand Colin, 2015, collection « Cursus », 192 p.

- Denis Woronoff, Histoire de l’industrie en France, 1994.

- Jean-Pierre Rioux, France of the Fourth Republic, Le Seuil, Tome 1, p. 120.