The simplest architectural structure, known since the Neolithic era. From ancient times to the present day, it has been used in all buildings covered with flat or gabled roofs. In the past, wooden or stone beams were laid on posts made of the same materia—today, natural stone is replaced with metal and reinforced concrete.

- Around 2500 BC: The Beginning of Column Design

- Around 700 BC: Formation of the Classical Order

- Around 70 AD: The Beginning of the Widespread Use of Arched Structures

- 318: The Return of Early Christian Architects to Wooden Roof Trusses

- 532: The Beginning of the Use of Domes on Pendentives by Byzantine Architects

- Around 1030: The Return to Arched Vault Construction in Romanesque Architecture

- 1135: Gothic Architects Give Arched Structures a Pointed Shape

- 1419: During the Renaissance, Baroque, and Classicism, Styles Are Formed Regardless of New Structural Innovations

- 1830: The Beginning of the “Railroad Fever” Led to the Widespread Use of Metal Structures in Construction

- 1850: Glass Becomes a Full-fledged Building Material

- 1861: The Beginning of Industrial Use of Reinforced Concrete

- 1919: The Integration of All Technological Capabilities in a New “Modern” Style

Around 2500 BC: The Beginning of Column Design

Ancient Egyptian architects remained faithful to the post-and-lintel system but gave meaning to architectural forms. The columns in their temples began to depict a palm tree, a lotus, or a bundle of papyrus. These stone “thickets” symbolize the afterlife forest, through which the souls of the deceased must pass to a new life. Thus, architecture became a visual art. Later, in Mesopotamia, architecture was also used to create large sculptures, but they preferred to sculpt bulls, griffins, and other creatures of the animal world.

Around 700 BC: Formation of the Classical Order

The Greeks made architecture itself the theme of architecture as an art form, specifically focusing on the work of its structures. From this point forward, the supports of the post-and-lintel system not only decorated buildings but also visually demonstrated that they were supporting weight. These elements sought to evoke sympathy from viewers and, for greater credibility, mimicked the structure and proportions of human figures—male, female, or maiden.

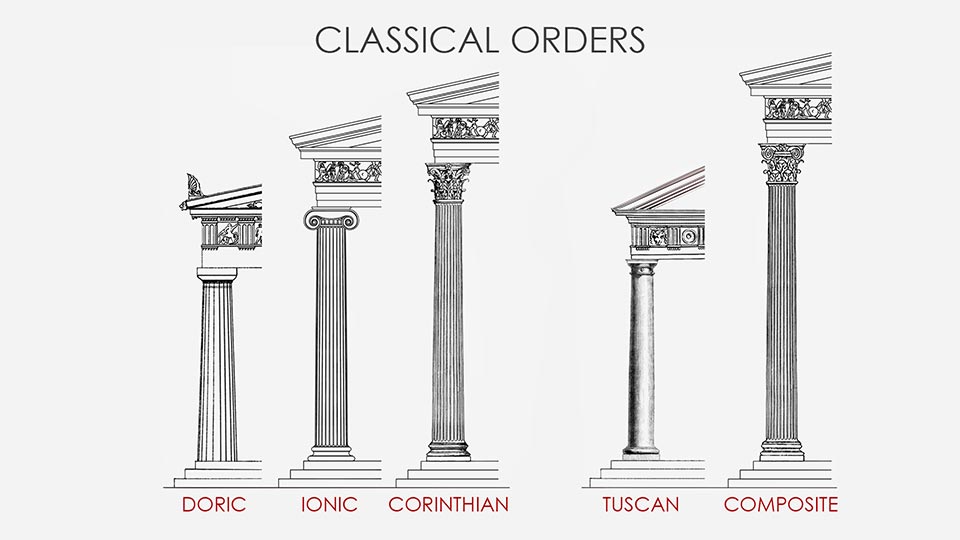

This strictly logical system of supporting elements is called an order. Typically, three main orders are distinguished: Doric, Ionic, Corinthian.

Additionally, two supplementary orders are recognized: Tuscan, Composite.

The development of these architectural orders marks the birth of European architecture.

Around 70 AD: The Beginning of the Widespread Use of Arched Structures

The Romans began to widely use arches and arched structures (vaults and domes). While a horizontal beam can crack if it is too long, the wedge-shaped parts in an arch under load do not break but compress, and stone is difficult to destroy by pressure. Consequently, arched structures can cover much larger spaces and bear significantly heavier loads.

However, despite mastering the arch, Roman architects did not invent a new architectural language to replace the ancient Greek one. The post-and-lintel system (i.e., columns and the elements they support) remained on the facades, but often it no longer served a structural purpose, instead functioning solely as decoration. In this way, the Romans transformed the classical order into mere decor.

318: The Return of Early Christian Architects to Wooden Roof Trusses

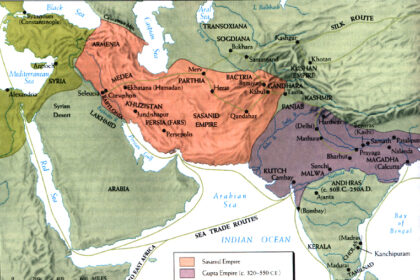

The fall of the Western Roman Empire brought down the economy of those territories we today call Western Europe. There was not enough money for constructing stone roofs, although there was a need for large buildings, primarily churches. Therefore, Byzantine builders had to return to wood and, with it, to the post-and-lintel system. The rafters—the structures under the roof, where some elements (braces), according to geometric laws, work not on bending but on tension or compression—were made of wood.

532: The Beginning of the Use of Domes on Pendentives by Byzantine Architects

A technological breakthrough in Byzantine architecture was placing a dome, invented back in Ancient Rome, not on round walls enclosing the inner space but on four arches, with only four points of support. Between the arches and the dome ring, double-curved triangles—pendentives—were formed. (In churches, they often depict the evangelists Matthew, Luke, Mark, and John—the four pillars of the church.) In particular, thanks to this construction, Orthodox churches have the appearance we are familiar with.

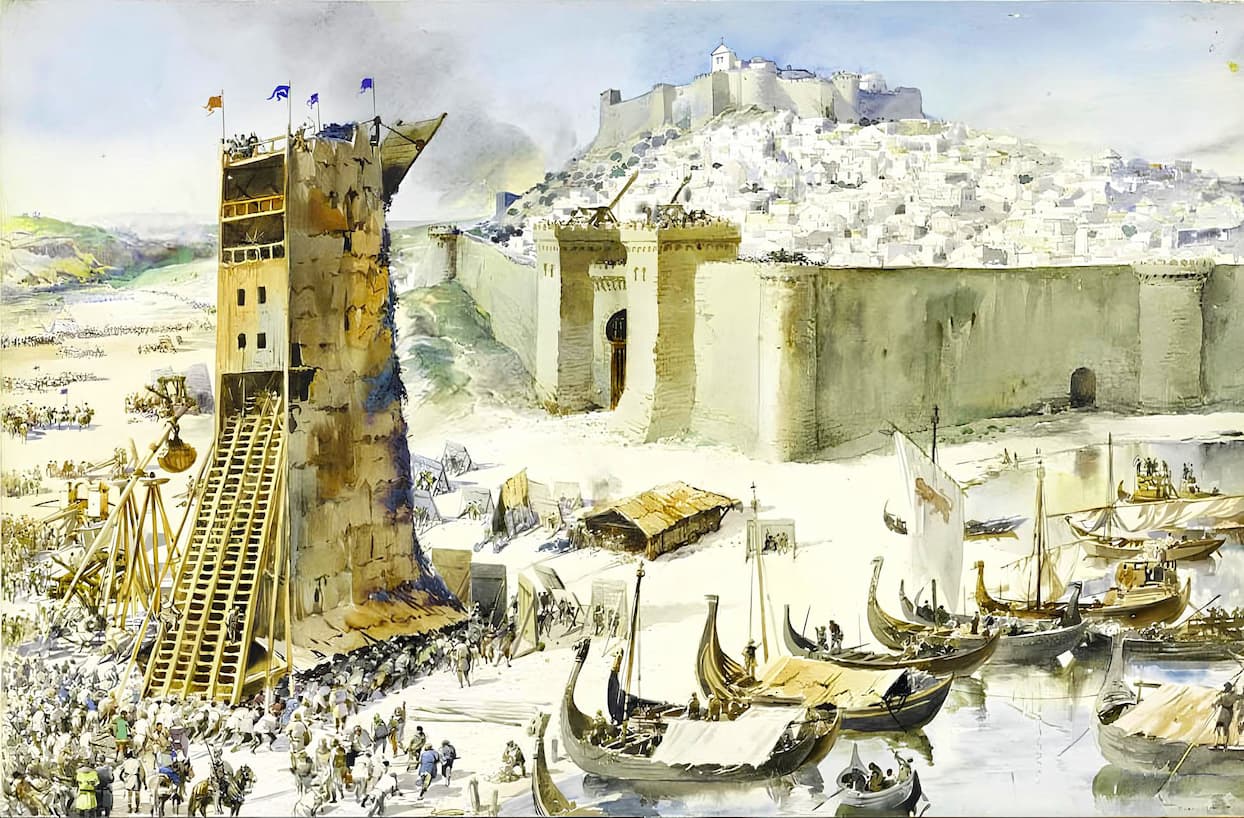

Around 1030: The Return to Arched Vault Construction in Romanesque Architecture

By the beginning of the second millennium AD, powerful empires were emerging in Europe, each considering itself the heir of Rome. The traditions of Roman architecture were revived. Magnificent Romanesque cathedrals were again covered with arched structures, similar to ancient ones—stone and brick vaults.

1135: Gothic Architects Give Arched Structures a Pointed Shape

Arches and arched structures have a serious drawback: they tend to “spread out.” Before Gothic architecture, architects combated this effect by building thick walls. Then, a new technique emerged: arches and vaults began to be made pointed. A structure of this shape exerts more downward force onto supports than sideways pressure. Furthermore, this system was supported on the sides by special “bridges”—flying buttresses—which extended from freestanding columns called buttresses. Consequently, the walls were freed from all loads, made lighter, or even eliminated entirely, giving way to glass paintings known as stained glass windows.

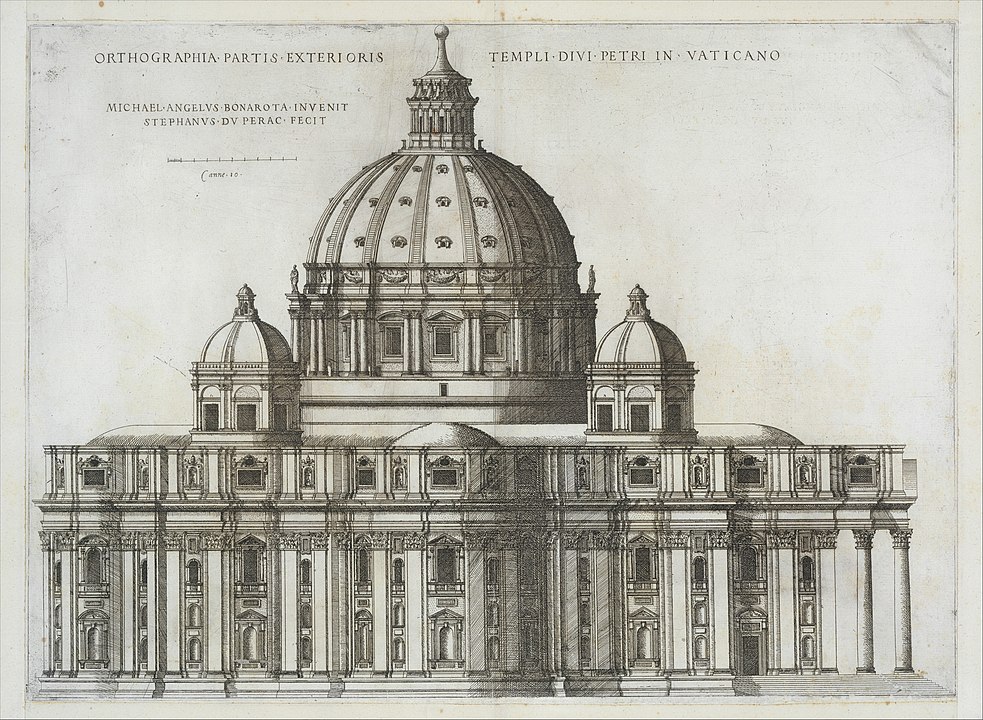

1419: During the Renaissance, Baroque, and Classicism, Styles Are Formed Regardless of New Structural Innovations

The Renaissance gave the world the greatest domes, but from this moment on, large styles no longer arose primarily due to construction innovations but rather as a result of changes in the worldview. Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque, Rococo, Classicism, and Empire were born more due to philosophers, theologians, mathematicians, and historians (and to some extent those who introduced fashionable manners) than to inventors of new roof structures. Until the Industrial Revolution, innovations in construction technologies ceased to be the determining factor in changing styles.

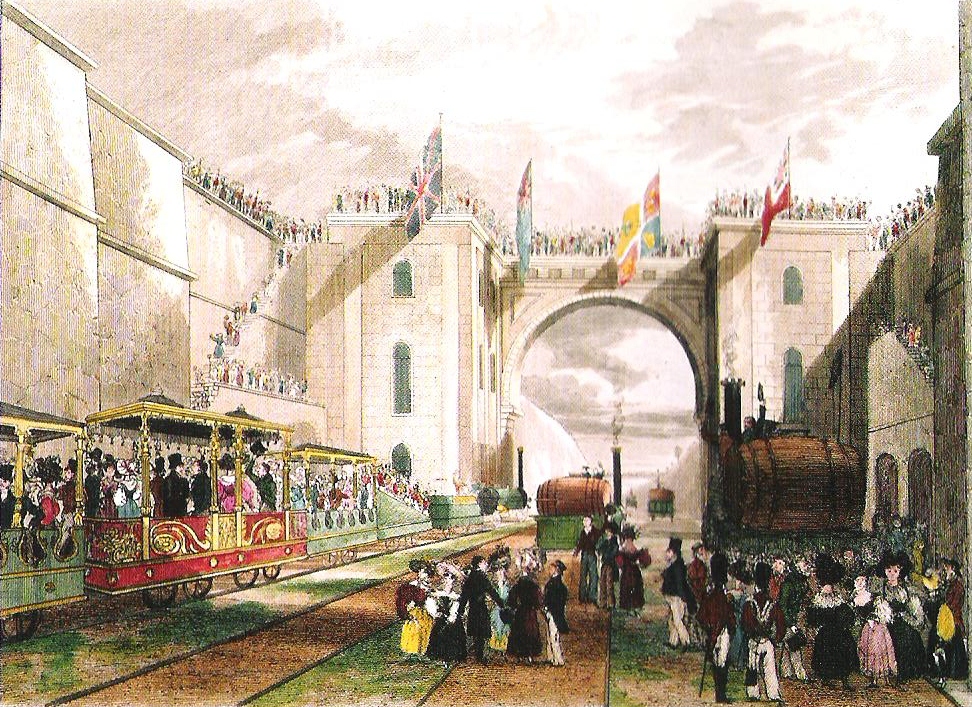

1830: The Beginning of the “Railroad Fever” Led to the Widespread Use of Metal Structures in Construction

Rails, initially intended only for railroads, turned out to be an ideal building material from which strong metal structures are easily created. The rapid development of land steam transport contributed to the growth of rolled metal production capacities, ready to provide engineers with any number of channels and I-beams. The frames of high-rise buildings are still made from such parts today.

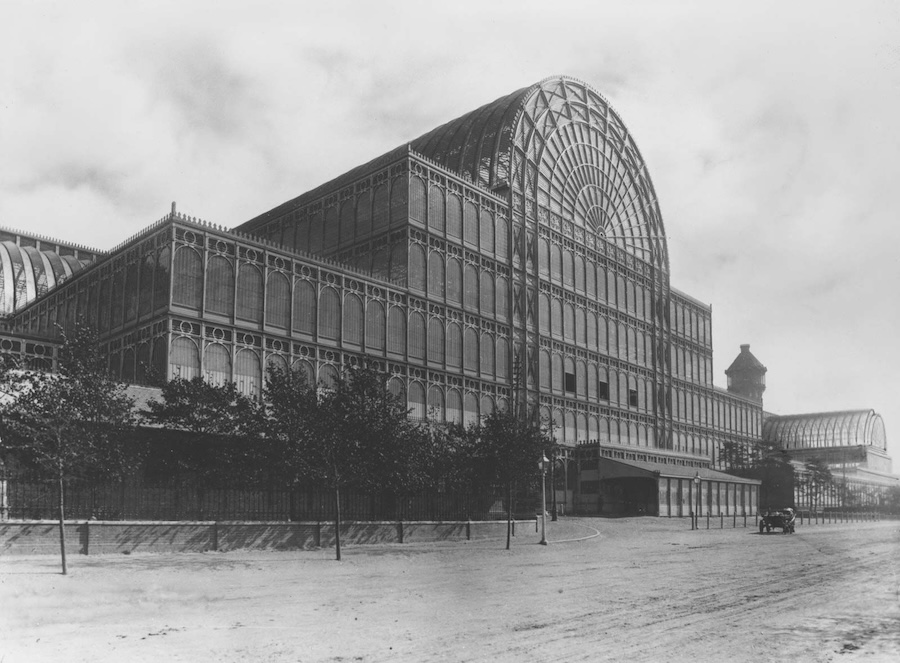

1850: Glass Becomes a Full-fledged Building Material

The factory production of large-sized window glass made it possible to develop construction technologies first for large greenhouses and then for grandiose buildings for other purposes, in which either all the walls or roofs were made of glass. Fairy-tale “crystal palaces” began to come to life.

1861: The Beginning of Industrial Use of Reinforced Concrete

Attempts to reinforce concrete date back to Ancient Rome. Metal rods for reinforcing roofs began to be actively used from the beginning of the 19th century. In the 1860s, a gardener named Joseph Monier, while searching for a way to make garden tubs more durable, accidentally discovered that embedding metal reinforcement in concrete significantly increased the strength of the resulting element. In 1867, the invention was patented and subsequently sold to professional engineers who developed methods for using this innovative technology.

However, the enterprising gardener was only one of several pioneers of this new construction technology. For instance, in 1853, French engineer François Coignet built a house entirely of reinforced concrete, and in 1861 he published a book on its application.

1919: The Integration of All Technological Capabilities in a New “Modern” Style

In his manifesto published in the magazine “L’Esprit Nouveau,” Le Corbusier, one of the leading modernist architects, formulated five principles of modern architecture. These principles returned architecture to ancient ideals—not externally but fundamentally. The image of the building once again truthfully reflected the work of structures and the functional purpose of volumes.

By the beginning of the 20th century, facade decoration was perceived as deceit. There was a need to return to the origins, drawing inspiration from ancient Greek temples that honestly depicted the work of structures. However, modern roofs were now made of reinforced concrete, whose significance lies in its ability to resist tearing where a part is subjected to bending, thanks to embedded reinforcement. Consequently, modern structures could span almost any width.

As a result, buildings could be entirely devoid of columns and decorations, featuring continuous glazing and thus acquiring the “modern look” familiar to us today.