Won by General Napoleon Bonaparte over the Mamelukes of Egypt on July 21, 1798, the Battle of the Pyramids is the most prestigious (and rare) French victory of the Egyptian campaign. It left to posterity one of the most famous quotes from the future emperor: “From the top of these pyramids, forty centuries of history are watching you!”… Following in the footsteps of Caesar and Alexander, the young general led the armies of the Republic into a mad military and scientific adventure on the land of the Pharaohs, occupied by the legendary Mamelukes… At the gates of Cairo, their mythical cavalry, reputed to be the best in the world, was crushed by the infantry of the French expeditionary force. This is the story of an “Egyptian Azincourt” at the foot of the millennia-old pyramids.

The Egyptian Campaign

In 1798, the Directory entrusted General Bonaparte with an expedition to the eastern Mediterranean aimed at disrupting British interests in the East. On May 19, 1798, the French fleet departed from Toulon with 32,000 men aboard.

Evading the vigilance of the English navy, the French expeditionary corps of the Egyptian campaign seized Alexandria on July 2, 1798. Posing as a liberator of Egypt by driving out the tyrannical Mamelukes with the blessing of the Sublime Porte, General Napoleon Bonaparte was, in reality, seeking to establish the first colony of the French Republic. A colony where scholars were tasked with creating the first social, agricultural, and industrial structures for long-term exploitation.

Additionally, it was intended to sever a major commercial route from the English and serve as a base for a grand expedition towards the Far East, towards India, where they would fight the hereditary enemy alongside Maharajah Tipu Sultan. Hoping for the passivity of the Ottoman Empire in the face of this fait accompli, Bonaparte aimed to catch the 10,000 Mamelukes, who controlled the country under the command of twenty Beys, by surprise.

Bonaparte had 40,000 men, but morale was low among the French soldiers, who, instead of finding an Eden, encountered a poor, starving country where the majority of the population consisted of wretched souls tormented by vermin. Bonaparte, therefore, aimed to move swiftly, to surprise his enemy and uplift his army with the euphoria of victory. The temperature reached 50°C in the shade, and the thick Western uniforms were not suited to this stifling climate.

The most sensible, reasonable path was the sacred river of Egypt, the Nile, a miraculous serpent of life in the midst of this arid land. But it was also the most predictable path, where they would be expected, and Bonaparte decided to bypass any potential defense by cutting directly through the desert, leaving only a flotilla to sail down the river from Rosetta to join the army at Ramanieh.

The Desert Crossing

Desaix’s division led the vanguard, followed by Reynier, Dugua, Bon, and Vial’s divisions. A week of desert crossing, a week of unimaginable suffering under a blazing sun. Water was scarce, the wells were filled with stones or clogged with salty earth, the cisterns found along the way were empty or poisoned, and they had to dig to find a source. Soldiers rushed and crushed each other for a sip of water; in the rear guard led by Bon, they were ordered to use teaspoons!

Food was also scarce, and the miserable huts encountered along the way did not provide the necessary supplies. Without mills or ovens, the army could not make use of the few wheat fields. The most prudent soldiers carefully preserved some melons picked before departure, and especially beans.

Foragers were sent to buy provisions in the few villages encountered, but the hostile and impoverished population had mostly fled. In Damanhour, the foragers of Reynier’s division were greeted with gunfire, and the battle ensued, with the resisters executed. The desert expanses thinned the ranks, disillusioned, exhausted, disoriented by mirages, suffering from ophthalmia, overwhelmed by the heat and deprivation, men resorted to suicide or fell behind… Around them lurked the Bedouins, predators circling a flock, who, unable to attack head-on, waited for a weakened individual to fall behind…

Those unlucky enough to fall into their hands were brutalized, slashed, and raped, and often only bloodied bodies were found. The atmosphere was ripe for revolt, as the veterans of the Army of the Rhine did not hold the same respect for the general-in-chief as those of the Army of Italy. Even the generals doubted, lost their tempers, and trampled on their hats. Desaix bluntly told Bonaparte: “If the army does not cross the desert with the speed of lightning, it will perish.” On the map, the route was only about a hundred kilometers, but the conditions were extreme, and they quickly decided to march at night.

Chebreiss: The Prelude to the Battle of the Pyramids

At the end of the journey, the soldiers’ joy at the sight of the Nile was equal to that of the Hebrews discovering manna from heaven. The half-brigades scattered, and everyone threw themselves into the river. A watermelon field marked this long-awaited moment. But already some Mamelukes were approaching, and they were chased away by gunfire. On July 10, Murad Bey sent a flotilla and 4,000 cavalry to meet the French. The clash occurred at Chebreiss, where the division formation in squares was inaugurated: these squares were actually rectangles, formed by six rows of infantry on the long sides, three rows on the short sides, with cannons loaded with grapeshot at the corners, and the cavalry, civilians, and baggage protected in the center.

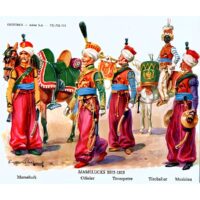

The Mamelukes had blind faith in their cavalry, reputed to be the best in the world. Overconfident, they looked down on the invaders, thinking they would crush them at the first charge. Circassian slaves trained from a young age for war, the Mameluke cavalrymen were overarmed warriors who, carrying all their wealth in their saddlebags, fought fiercely to defend their possessions.

Adorned on all sides and emitting wild howls, their frenzied charge was enough to impress any ordinary mortal. But the French infantrymen were no longer easily impressed; most of them were veterans of the Rhine or Italy and waited calmly for the order to fire the deadly volley. At the Battle of Chebreiss, the Mamelukes’ counterattack was stopped dead by the discipline of the French soldiers. They retreated, leaving behind 300 cavalrymen, 400 to 500 infantrymen, and nine iron cannons on the burning sand.

On the river, the fight was fierce as the French fleet was boarded by Egyptian ships. The sailors, dismounted cavalrymen who were aboard, as well as the civilians (including Monge, Berthollet…), showed bravery and repelled the attackers. The Egyptian fleet withdrew as the current carried away the remains of a gunboat.

“From the top of these pyramids, forty centuries are watching you!”

The Beys were not as subdued by this defeat; they continued to haggle, no real recognition was made, and they still ignored where the enemy was coming from. Although they were certain of Bonaparte’s presence on the left bank of the Nile, they did not take the necessary measures to defend Cairo: their army could have entrenched itself on the right bank and patiently waited for a landing that it could have repelled at any point thanks to its cavalry’s mobility. Instead, Mourad Bey settled on the left bank, while Ibrahim Bey remained on the right in case a French army had landed on the other side.

After allowing his troops a bit of rest, Bonaparte resumed his relentless march toward Cairo. The army trudged through the burning sand dunes, constantly harassed by the Bedouins. On July 19, the village of Abou-Nichoubi put up fierce resistance against the French vanguard. The repression was ruthless, with civilians executed and houses burned. This brutal example rallied some of the local sheikhs. The divisions kept each other within sight, and on July 20, the pyramids appeared on the horizon.

Informed by spies of the isolation of Mourad’s army on the left bank, the attack was decided. At two in the morning, the army set off and marched 24 km to engage the enemy in the early afternoon of July 21, 1798. There, Bonaparte launched his famous proclamation (perhaps edited later):

“Bonaparte, member of the Institute, commander-in-chief.

Soldiers!

You have come to these lands to tear them from barbarism, to bring civilization to the East, and to free these beautiful regions from the yoke of England. Remember that from the top of these Pyramids, forty centuries are watching you!”

The Bey, along with his women, wealth, and slaves, had entrenched himself with 6,000 men—peasants, Nubians, and Janissaries—in the village of Embabeh, on the banks of the Nile, where Ibrahim’s boats and galleys sailed. Along the river, the Mamluk cavalry and about 20,000 irregulars were positioned. These latter forces, being mere peasants armed with sticks and clubs, had little military value, but the goal was to form a mass. Without tents to sleep in or organized supplies, they were often forced to return home in the evening.

Bonaparte had his divisions form squares and advanced them toward the heights of Waraq-el-Hader (2 km from the enemy camp), while Mamluk horsemen retreated as the army advanced. The right wing, commanded by Desaix, anchored itself at the village of Biktil and moved beyond it. The village, offering some resources and formidable defensive positions, became a strategic point where Reynier and Desaix positioned grenadiers, dismounted dragoons, line infantry, light infantry, and an artillery company.

Forming a curved line, the French divisions (Desaix, Reynier, Dugua, Vial, and Bon) stretched from the pyramids to the Nile, where Bon’s division anchored itself. Once in position, the order to rest was given, and the men dispersed to eat and drink. Suddenly, multicolored dots began to stir on the horizon.

The Battle Preparations

The Mamluks, feeling threatened with encirclement by the right wing’s advance, took up positions. Hastily, the French rejoined the ranks, reformed their squares, and prepared to face the best cavalry in the world. The first rank aimed bayonets at mid-height, the second and third ranks stood at the ready, weapons at shoulder, prepared to fire, and the last three ranks were kept in reserve. After an artillery salvo, the Mamluks charged, their hooves pounding the ground, a cloud of dust rising as golden harnesses flashed through the air.

The French soldiers remained impassive, shoulder to shoulder.

Despite a fierce headwind, this half-human, half-animal torrent hurled itself furiously at Reynier’s and Desaix’s divisions, emitting savage cries. At half-range, the French officers gave the order to fire, and a deadly volley brought down the first rank, which collapsed amid the neighing of horses and the cries of the wounded, trampled by their comrades. A second volley felled the riders in a cloud of smoke. The charge, shot down at point-blank range, faltered just steps from the French squares; the cavalry turned back, while the most fanatical impaled themselves on the wall of bayonets.

Some wounded Mamluks found the strength to crawl toward the French ranks, attempting to cut the infantry’s legs with their scimitars, but they were slashed to pieces. The cavalry circled in frustration. Trying to bypass the position, they charged between Desaix and Reynier but were caught in a crossfire. Unfortunately, the squares weren’t staggered enough, and friendly fire caused around twenty casualties. Within five minutes, 300 cavalrymen had been killed, about twice as many were wounded, and a panicked part of the Mamluks fled the battle. The others charged the village of Biktil, where they were repelled by the French, who were entrenched on rooftops and in gardens.

Some soldiers sent to fetch water from a nearby village hurried back to join the squares. A dragoon was caught by a Mamluk rider, and an epic duel ensued, as the entire army held its breath. Captain François recounted:

“At the moment when the Mamluks charged toward the village of Belbeis, several soldiers escaped and rejoined their divisions. A dragoon from the 15th regiment was attacked by a dismounted Mamluk; a fight broke out between them in the middle of Desaix’s and Reynier’s divisions. These two generals ordered a ceasefire on the side where the two adversaries were locked in combat. Finally, the dragoon killed the Mamluk and returned to the square; he had taken his enemy’s saber, a saber with a solid silver scabbard, as well as his dagger and pistol.”

The Battle of the Pyramids

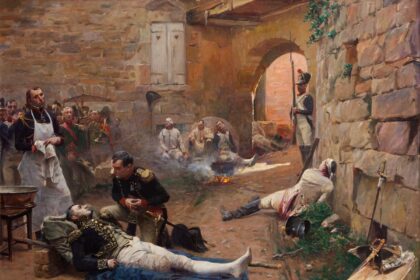

In twenty minutes of battle, the cavalry disbands; a few riders take refuge in a park of palm trees to the west, from where they are driven out by skirmishers. The others return to the camp, spreading panic in Embabeh, where the Cairenes rush to the boats to save their lives. Meanwhile, Desaix and Reynier’s soldiers, who bore the brunt of the attack, seize the spoils, recovering equipment and treasures left in saddlebags and belts.

Bonaparte, galloping from one square to another, orders Dugua’s division to advance and position themselves between the Mamluks and Embabeh, and instructs Bon and Vial to capture the village. Two detachments form into columns and launch the assault, using a ditch as cover from enemy artillery. Vial maneuvers around the village from the west, while Bon sends Marmont and Rampon to attack. The forward flankers are charged in turn; forming squares, they fire point-blank at the Mamluks, so close that the gunpowder ignites their tunics, which continue to burn on the corpses.

The defenders fire their poorly maintained artillery but do not have time to reload before the French fall upon them. The Cairenes scatter, and only about 1,500 Mamluks remain, who are either killed or thrown into the Nile. The attackers capture the village, chasing the fleeing Egyptians along the Nile until they are forced by a wall to plunge into the river en masse.

Before Ibrahim’s reinforcements could land, the rout was complete. Many of the fugitives drown in the sacred river, including Ibrahim’s son-in-law, who is repeatedly struck by an enraged oarsman, killing him. Some sailors sink their ships to prevent them from falling into French hands, while Mourad’s vessel, filled with gunpowder, runs aground and is set on fire. Meanwhile, Desaix’s division resumes its march towards the Giza Plateau, pushing Mourad Bey’s last warriors before them.

A Victory That Forges Bonaparte’s Glory

In this memorable battle, which would become a significant episode in the Napoleonic epic, the French suffered 300 killed and wounded. On the other side, the Mamluks lost between 1,500 and 2,000 men, 20 cannons, 400 camels, and all the baggage from Mourad’s camp. Mourad himself, wounded, fled to Upper Egypt, while Ibrahim Bey hastened towards Syria. Bonaparte declared that he had crushed the bulk of the Mamluk forces, though this needs to be tempered by the fact that, as was their custom, the Mamluks fled once they realized victory was impossible.

Nevertheless, the general-in-chief could now return to Cairo, deserted by its elites, and proclaim Egypt liberated. Indeed, he had just conquered all of Lower Egypt and regained the confidence of his army. Enriched by the spoils and finally camping on the fertile banks of the Nile, the French reveled in their victory over an exotic enemy of incomparable bravery. A clash of cultures, infantry maneuvers had prevailed over the most violent charges. Disconcerted, the Egyptians remained convinced that the French soldiers must have been tied together in their squares to maintain such formation.

The Cairenes, who had fled and been looted by Bedouins, gradually began to return to the Egyptian capital, somewhat reassured by the behavior of the victor.

Although the battle took place at Embabeh, Bonaparte rightly believed it would have a greater impact on public opinion, and enhance his personal glory, by associating it with the pyramids, symbols of Pharaonic Egypt.