In the tumultuous era of World War II, with nations embroiled in conflict, two key leaders emerged to steer their respective nations through the storm. Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and Franklin D. Roosevelt, President of the United States, would come to symbolize the alliance that played a pivotal role in the ultimate victory over the Axis powers.

The Casablanca Conference was a meeting of Allied leaders held in Casablanca, a city in (then) French Morocco, from January 14 to January 24, 1943, under the code name “SYMBOL.” It is regarded as the most controversial conference of World War II.

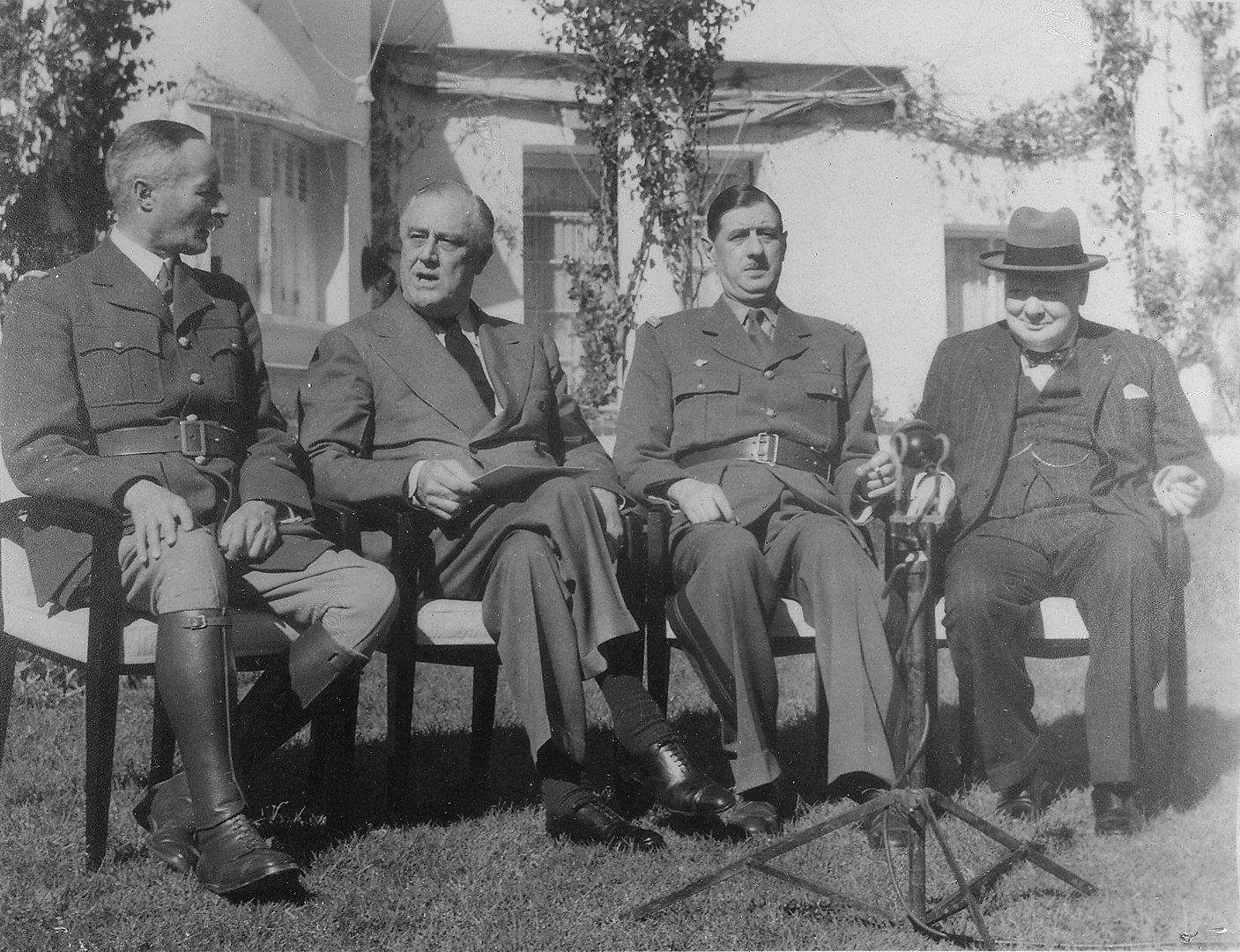

At the conference, on the leadership level, participants included American President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Joseph Stalin was absent; he had been invited but declined to attend, citing the impending Battle of Stalingrad. Their top military commanders and significant military figures were with both leaders. Also present were French rival generals Charles de Gaulle and Henri Giraud.

Casablanca was chosen for its strategic location in North Africa and because it was readily accessible to President Roosevelt, who was already in the region for health reasons. Additionally, it was a suitable location for discussions about the ongoing North African Campaign.

Before the Conference

On November 8, 1942, the Allies landed on the shores of (then) French North Africa, executing an operation codenamed Operation Torch. The decision for this operation was made despite initial skepticism from the Americans and under pressure from Stalin, who demanded that the Anglo-Americans open a front in Western Europe as quickly as possible to relieve the Red Army on the Eastern Front. Indeed, “Operation Sledgehammer” was planned to target the ports of Brest and Cherbourg, aiming to establish a small bridgehead on European soil.

The Americans initially favored the plan, but the British strongly opposed it, correctly asserting that they lacked sufficient landing craft and the capability to support such an undertaking from air and sea. Thus, the implementation of Operation Torch commenced, with strong reluctance from the Americans, who did not consider “the road to Berlin passing through North Africa.”

By the beginning of 1943, it was already evident that the outcome of the operation was as expected: German and Italian forces would be definitively expelled from North Africa. Some issues remained to be clarified, such as addressing the problem posed by Admiral Karl Dönitz’s submarines in the Atlantic (Battle of the Atlantic), the allocation of forces on various war fronts, determining the next steps for the Allies, and, finally, Churchill raising the question of how to reconcile the conflicting French commanders.

The British desired the continuation of operations in the Mediterranean. Churchill had even referred to Italy as the “soft underbelly of Europe.” In contrast, the Americans wanted an invasion through the English Channel, knowing that in such a scenario, the main burden would fall on the British, allowing them to conserve resources for the immense effort they were undertaking in the Pacific against Japan.

Preparation

The conference took place in the Anfa neighborhood of Casablanca, and the discussions were held at the eponymous hotel (Anfa Hotel). Two mansions were provided for the accommodation of the leaders; another two were allocated for the chiefs of staff; and the entire neighborhood was surrounded by barbed wire, with armed guards stationed behind the wire perimeter.

Essentially, the conference did not have a serious objective. Without the presence of Stalin, it lost a significant part of its significance. All its issues could have been resolved without it. However, according to presidential advisor Harry Hopkins, President Roosevelt “wanted to take a trip.” Moreover, as he did not desire much formality, he asked Churchill “not to burden his foreign minister,” as he would do the same. In reality, Roosevelt circled half the globe before reaching Casablanca, even passing through Trinidad. This unnecessary move almost cost the Allied leadership dearly: the aircraft carrying Churchill caught fire, and Eisenhower’s plane lost two engines in flight, causing the Supreme Commander to land with a parachute on his back and suffer a knee injury from the impact.

On the other hand, Churchill had premeditated what he would request from the Americans, which was nothing but the expansion of hostilities in the Mediterranean. He loaded a ship with documents (referred to as a “floating staff” by Cartier) and brought all his chiefs of staff with him, just like Roosevelt did. He also asked De Gaulle to accompany him without informing him beforehand. He justified the lack of information by arguing that if the conference had been announced, it would have required extensive security measures.

The stubborn Frenchman, aware that his opponent’s headquarters were precisely there, initially issued a categorical “no,” and Churchill left on his own. He then called both Giraud and De Gaulle “on behalf of the American president and the British prime minister.” Giraud arrived immediately, while De Gaulle continued to refuse, claiming it was purely a French matter and did not require foreign intervention. The irritable Churchill became so annoyed that he threatened De Gaulle, sending him a stern telegram stating that he would withdraw his support and sideline him. Under this intense pressure, De Gaulle yielded, although he attended the conference only on the ninth day.

Participants of the Casablanca Conference

British Side

- Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

- Admiral Sir Dudley Pound (Sir Alfred Dudley Pickman Rogers Pound)

- Air Chief Marshal Charles Portal (Charles Frederick Algernon Portal)

- Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder

- General Sir Alan Brooke (Sir Alan Francis Brooke)

- General Sir John Dill

- Air Chief Marshal Sir Harold Alexander, head of British forces in the Middle East

- Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten

- General Sir Hastings Ismay

American Side

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, President of the United States

- General of the Army and Air Force Henry Arnold (Henry Harley “Hap” Arnold)

- Admiral Ernest King, head of the U.S. fleet

- General George Marshall, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army

- General Dwight Eisenhower, head of “Operation Torch”

- Averell Harriman, presidential advisor

- Harry Hopkins, presidential advisor

- Robert Murphy, special representative of the president on Eisenhower’s staff

- Brigadier General Elliot Roosevelt, son of the president

French Side

- General Charles de Gaulle, leader of the “Free French”

- General Henri Giraud, the military commander of French North Africa

Results of the Casablanca Conference

The fundamental decision of the conference was that the Allies’ struggle should continue until what is termed the “bitter end,” meaning until Nazi Germany unconditional surrender. This unconditional surrender requirement was applied to both Italy and Japan. It was also agreed that none of the Allies would accept a separate surrender from any Axis power; for example, Italy had to surrender to the Allies and not to Britain or the United States.

Winston Churchill opposed the proposal for unconditional surrender. He did not believe that a vengeful approach toward Germany was necessary. Later, he clarified that “The term ‘unconditional surrender’ does not mean that the German people will be enslaved or destroyed.” Churchill rightly feared, as events proved, that these two words would undermine any internal opposition in Germany, providing the Nazis with the rallying point they needed to fight to the death. Joseph Goebbels, in his propaganda, effectively exploited these two words. The opponents of the Adolf Hitler regime had no choice but to halt their actions.

The declaration of unconditional surrender meant that the Allies would accept nothing less than complete and total surrender from the Axis powers. It set a clear and uncompromising goal for the defeat of the enemy.

The British presented strong arguments, and Churchill personally opposed Marshal’s proposal for a “small” invasion of the northern French coast in the summer of the same year. He argued that such an operation, given the Luftwaffe’s air superiority in the region, would result in an easy victory for Hitler. Additionally, the available landing craft at that time were numerically insufficient to transport the required troops, and the presence of German submarines was particularly worrisome.

Instead, Churchill approved providing strong support to the Americans from Australia and New Zealand, Commonwealth members, in the Pacific theater. He also assured the expansion of British operations in Burma to strengthen Chiang Kai-shek in China. In return for these gestures, Roosevelt agreed to the Allied invasion of Sicily. It was also agreed to initiate and intensify air raids on German territory from British airfields, involving both the RAF and the U.S. Air Force.

This conference marked the last occasion where Churchill could dictate the goals of the Allied effort. After this meeting, the Americans realized that, due to their strength, they were the primary driving force of the Alliance and would start acting accordingly.

During the conference, the news of the fall of Mussolini’s regime and Italy’s conditional surrender reached the participants. The Allied leaders discussed the implications of Italy’s surrender and how to capitalize on it.

Resolution of the French Crisis

Initially, the two French leaders, though strong opponents of the Vichy France, had developed an atmosphere of intense coldness, if not hostility, in their relations. These “reservations” had worn out both Churchill and Roosevelt. The American president, on the other hand, viewed De Gaulle as a representative of the “old” France, with tendencies toward colonialism and autocracy, while also considering him influenced. Conversely, Giraud believed that De Gaulle had been involved in the assassination of Admiral Darlan (to be precise, he believed that De Gaulle had sent Darlan’s assassin).

On Sunday, January 24, the last day of the conference, Churchill and De Gaulle have yet another stormy discussion, during which De Gaulle insists on not committing to anything. Later, the two men meet with Roosevelt, who, after unsuccessful attempts to draft a joint communiqué, decides to adopt a different approach with De Gaulle.

He engages in a calm conversation, asking him if he would agree to shake hands with Giraud. De Gaulle responds with a “yes.” “And will you do this in front of the photographers?” “I shall do it for you,” replies the Frenchman. Journalists are called into the room, capturing a photograph of the two men exchanging the handshake, symbolizing reconciliation. Giraud even agrees to send a representative to organize direct contact between French Africa and London (De Gaulle’s headquarters). From this perspective, the conference held great significance for France. The BBC reported: “the two Frenchmen became the joint chairmen of the French Committee for National Liberation.”