Charles VII (1403-1461), known as “the Victorious”, was a king of France from the Valois dynasty. His reign, which lasted nearly forty years (1422-1461), is inseparable from the end of the Hundred Years’ War. It covers one of the richest periods of events in French history and could also be seen as a time when the Capetian dynasty appeared on the brink of disappearing. The epic of Joan of Arc allowed the “King of Bourges” to regain his throne and legitimacy, initiating the reconquest of his kingdom from the English.

Having become Charles VII the Victorious, he would long remain in the shadow of the glory of the Maid of Orléans. This once-overlooked sovereign, now rehabilitated, restored the authority of the monarchy in France, reforming and modernizing finances and the military.

Charles VII: The “Little King of Bourges”

The son of Charles VI the Mad and Isabeau of Bavaria, Charles became dauphin in 1417 after the suspicious deaths of his two elder brothers. He appeared frail and ill-equipped to bear the heavy responsibility of restoring the name and prestige of a faltering monarchy. Expelled from Paris during the struggle between the Armagnacs and the Burgundians, he took refuge in Bourges, where he maintained a small court with his last loyal followers. Meanwhile, the King of England seized Normandy, and John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, took control of the government by allying with his mother, Isabeau of Bavaria, who had declared Charles a “bastard.”

John the Fearless attempted to secure an alliance with the dauphin to control him. However, their meeting at Montereau degenerated into an altercation, and John the Fearless was killed. The vengeance of the new Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, and Isabeau of Bavaria fell upon Charles. He was disinherited in favor of the King of England, Henry V, through the Treaty of Troyes (1420), signed by Isabeau and Charles VI, who was no longer in full possession of his faculties.

Henry V claimed the crown of France while preserving its institutions. Isabeau of Bavaria resisted in vain. The premature death of Henry V on August 31, 1422, followed by the death of Charles VI on October 21, did nothing to change the dual Lancastrian monarchy, which passed to Henry VI, with the Duke of Bedford acting as regent. However, the dauphin now claimed the throne as Charles VII, and the war for the crown began.

Yolande of Aragon and the Victory at La Brossinière

Charles, with a rather lackluster character, was poorly surrounded and placed too much blind trust in unreliable advisors who cast no shadow over him, unlike the flamboyant lords of the time. The young Charles found providential support in Yolande of Aragon, the wife of the Duke of Anjou, who happened to be his mother-in-law. Through patient effort, Yolande forged alliances and reconciliations to present a united front against the invader.

In 1423, the Battle of La Brossinière marked the first significant victory for the French armies. After a raid led by the Duke of Suffolk, Lord William Pole, across Maine and Anjou, Queen Yolande of Aragon convinced several supporters of her son-in-law, the King of France, to intervene militarily to avenge the damage done. Ambroise de Loré, along with John VIII of Harcourt, Count of Aumale and Mortain, among others, gathered their troops and prepared an ambush on the return path of the English.

After a brief skirmish between scouts, the French knights charged in battle formation, forcing the English to dismount. Despite solid resistance, the English troops were decimated, and few soldiers escaped French reprisals. This victory marked the starting point for a gradual reconquest of French lands.

Joan of Arc and Charles the Victorious

Militarily, the situation remained precarious despite the success at La Brossinière. The English won several victories near Crevant (1423) and Verneuil (1424). Most notably, they laid siege to Orléans. If the city fell, the English would gain access to the south of the Loire and reach Charles in his last refuge. It was at this moment that a young shepherdess from Lorraine, Joan of Arc, intervened providentially.

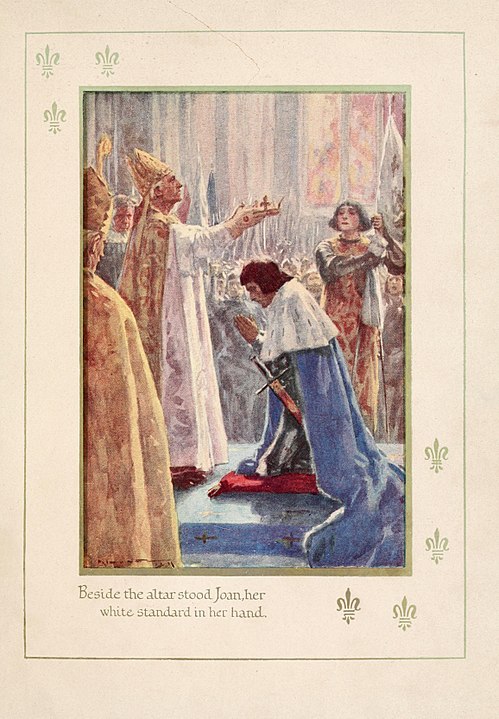

Charles regained his legitimacy only after being recognized by Joan of Arc, who liberated Orléans (1429) and had him crowned at Reims on July 17, 1429. Together with Joan, he undertook the reconquest of the kingdom, partly occupied by the English and their Burgundian allies. While they succeeded in reclaiming parts of the regions north of the Loire, Joan of Arc was captured and burned in Rouen (May 30, 1431). Charles VII made little effort to save her, and this is often referred to as a “cowardly abandonment.”

To detach the Burgundians from the King of England, Charles VII made significant concessions to Duke Philip III the Good of Burgundy in the Treaty of Arras (1435). The Anglo-Burgundian alliance was broken. Paris was reconquered, and the king made a triumphant entry into the city in 1437 but stayed only briefly, preferring his castles in Berry and Touraine. Normandy and then Guyenne (1450-1453) were retaken thanks to remarkable military leaders.

Rouen rose up and opened its gates to Charles VII, who made a triumphant entry alongside Jacques Cœur (1449). The English retaliated by sending an army, which landed in Cherbourg and marched toward Caen, only to be defeated by the French near Formigny (1450 / Battle of Formigny). In Guyenne, victory at the Battle of Castillon (1453) drove the English out. Soon, the English retained only Calais in France. With the Hundred Years’ War over (although no formal treaty was signed), Charles VII focused on reorganizing his kingdom.

The Reforms of Charles VII

He fought against the Écorcheurs (mercenaries who terrorized the countryside) by maintaining permanent troops tasked with restoring security and summoned the Estates General at Orléans. Some lords, unhappy with the progress of royal authority and encouraged by the Dauphin Louis (the future King Louis XI), rebelled. Charles triumphed over these revolts, known as the “Pragueries,” named after the disturbances in Bohemia. Between 1445 and 1448, he established a permanent army, consisting of a cavalry of compagnies d’ordonnance, recruited from the nobility, and an infantry of francs-archers, composed of commoners exempted from the taille tax (hence their name).

Currency was stabilized, regular taxes were levied, making it unnecessary to convene the Estates General, and France experienced a commercial revival, thanks to Jacques Cœur, the king’s chief financial officer. Charles signed the great ordinance of Saumur in the autumn of 1443, while various measures were taken to stimulate commerce in a country slowed by war. Privileges were granted to the major fairs of Lyon and Champagne, and silk weaving workshops were created. Demonstrating his ingratitude once again, Charles VII sacrificed Jacques Cœur to the jealousy of courtiers in 1453, and the great financier ended his days ruined and exiled.

Charles also addressed church matters at a national council held in Bourges in 1438. A “pragmatic sanction” gave French churches more autonomy and reduced the tributes that the pope collected on ecclesiastical benefices, such as annates, reserves, and expectations.

He ordered the various customary laws of the country to be written down, signaling the future unification of legal codes.

He created two new parliaments: one in Toulouse (1447) and another in Grenoble (1453). The end of his reign was marked by a commercial resurgence and the strengthening of royal authority. Ultimately, only one threat remained: the power of the Duchy of Burgundy.

A Favorite and a Rebellious Son

An innovation with a long-lasting legacy, the reign of Charles VII witnessed the public emergence of a royal mistress in the charming figure of Agnès Sorel. Around 1443, she became the king’s mistress, possibly following the manipulations of Pierre de Brézé, who then held significant sway over royal policy.

The king showered her with gifts, making her the lady of Loches, the lady of Beauté-sur-Marne (hence her nickname “Lady of Beauty”), and the countess of Penthièvre. He legitimized the three daughters she bore him in the early years of their relationship.

Her presence at court overshadowed that of Queen Marie of Anjou, as she enjoyed baring her shoulders and sporting extravagant dresses and hairstyles. She obtained her fashion items from the businessman Jacques Cœur, with whom she likely had an affair. Agnès Sorel exerted significant influence (though often exaggerated) over royal governance, often linked to the influence of the Brézé family.

King Charles VII married Marie of Anjou, having been raised at the court of Anjou, which explains the influence of Marie’s mother, Yolande of Aragon, on him. The royal couple had twelve children, five of whom survived. Among them was the Dauphin Louis, the future Louis XI. Estranged from his father, Louis troubled the court with his conspiracies, to the point that the king exiled him in 1447. Charles VII never saw his son again before his death in Mehun-sur-Yèvre on July 22, 1461.