The Christmas tradition in Germany encompasses traditional elements of the Christmas celebration. Like all traditions, Christmas customs in Germany vary regionally and are constantly evolving. The starting point is the celebration of the birth of Jesus Christ. In tradition, some older pre-Christian winter and light customs have been added and merged with Christian motifs. In other Central European countries, Christmas is celebrated similarly. The festive day is December 25th. The celebrations begin on the Holy Evening (also Holy Eve, Holy Night, Christ Night, and Christmas Eve), on December 24th. Depending on the denomination, the Christmas season ends on January 6th, the Feast of the Epiphany, or on the following Sunday, the Feast of the Baptism of the Lord. Today, Christmas symbols, songs, and decorations have already shaped the cityscape in many places since the end of November.

-> See also: 48 Countries That Celebrate Christmas Widely

History of Christmas in Germany

Christmas customs were Christianized in nativity plays as special spiritual performances and have been depicted in Christmas cribs since the 16th century. The scenic representations can be traced back to the 11th century in France. The contemporary Christmas celebration in the German-speaking region with a family gathering featuring a Christmas tree, Christmas carols, nativity scenes, gifts, and attending a church service is a cultural manifestation of the middle-class family of the 19th century (Biedermeier).

In folkloric and Germanic research, until the first half of the 20th century, including by the Brothers Grimm, it was presumed to be a very ancient tradition, and attempts were made to construct continuity back to Germanic antiquity. Thus, the world tree of Germanic mythology or the midwinter tree, was seen as a direct precursor to the Christmas tree. This also aligned with the ideology of National Socialism, which sought to blend the Christmas festival with Germanic and Scandinavian Yule traditions to establish it as the “Festival of the National Community under the Christmas Tree” (see Nazi Christmas cult).

Christmas Customs in Germany

Customarily, in Central Europe, the specific manifestation of Christmas and Advent traditions primarily arose in a region characterized by a cold and dark winter climate. In the Southern Hemisphere, Christmas coincides with summer, leading to different customs. The evergreen Christmas tree lacks a corresponding symbolic significance there.

Preparation

The Christmas celebration on December 25 is preceded by a four-week Advent period. Originally a fasting period, the Old Church placed it between November 11 and the Feast of the Epiphany on January 6. The present form of Advent dates back to the 7th century. Initially, there were between four and six Sundays in Advent, until Pope Gregory eventually fixed the number at four in accordance with the Roman Rite. However, in the Ambrosian Rite, the Advent period still lasts six weeks. Since 1917, Advent fasting is no longer mandatory under Catholic canon law. Numerous traditions accompany the Advent season, including the Advent calendar, indicating the remaining days until Christmas, hanging a Saint Nicholas boot on the doorstep on the evening before Saint Nicholas Day, and the Christmas market, prevalent in many cities.

Christmas Tree

In Central Europe, the Christmas tree (referred to as Christbaum in some German regions) is placed in churches, homes, and on large squares in towns, adorned with strings of lights, candles, glass balls, tinsel, angels, or other figures. The domestic Christmas tree often remains in the room long after Christmas, sometimes until the end of the liturgical Christmas season. Two candle-adorned Christmas trees have stood annually since 1621 at the Augustinians in Neustift, flanking the nativity scene.

The origin of the Christmas tree is likely the Tree of Life (Bible) from the widespread medieval mystery plays on December 24. From around 1800, the adorned Christmas tree could be found in the upscale residences of Zurich, Munich, Vienna, and Transylvania. Initially considered Protestant, it gradually gained acceptance among Catholics as well. Princess Henrietta of Nassau-Weilburg introduced it in Vienna in 1816. The Franco-Prussian War popularized the Christmas tree in France, and in 1912, the first “public” tree stood in New York.

The adorned Christmas tree is now a central element of the family Christmas celebration. Until the 18th century, it could only be found in royal courts and later among the bourgeois upper class. It gained popularity among the lower bourgeoisie, not least because the Prussian king, during the Franco-Prussian War against France, had Christmas trees set up in the trenches and field hospitals. Afterward, the Christmas tree continued to spread and assumed the central role in the ceremony of the domestic family celebration that is now considered self-evident (children standing in front of the closed door, candles on the tree being lit, the door opening, collective singing, joint opening of gifts, shared meal).

-> See also: All 15 Countries That Don’t Celebrate Christmas

Church Attendance

The collective attendance of Christmas Eve services such as Christvesper (“Christmas Vespers”), Christmette (“Midnight Mass”), or Christnacht (“Christmas Eve”) is not only a fixed component of Christmas for regular churchgoers among Christians. These services are usually well-attended in German-speaking regions. Services, often beginning on Christmas Eve with children’s services, take place on all Christmas days. The reading of the Christmas story from the Gospel of Luke and singing Christmas carols are part of the liturgy. Also, attending a performance of a Christmas oratorio is widespread in the time before and after Christmas, especially in the Lutheran Protestant tradition.

Nativity Scene

The most original Christmas custom is the tradition of the nativity play, which vividly recreates the Christmas story. Families gather around the nativity scene on Christmas Eve, commemorating the birth of Christ. The history of the nativity scene, now an integral part of Christmas, likely began in the 13th century, with the use of the nativity scene in worship possibly dating back to the 11th century. In the castle chapel of Hocheppan near Bozen, around the year 1200, the birth of Jesus was first depicted in the German-speaking region. This representation culminated in the Christmas celebration before the nativity scene and Christmas tree.

Christmas Gift-Giving

St. Nicholas and Christ Child

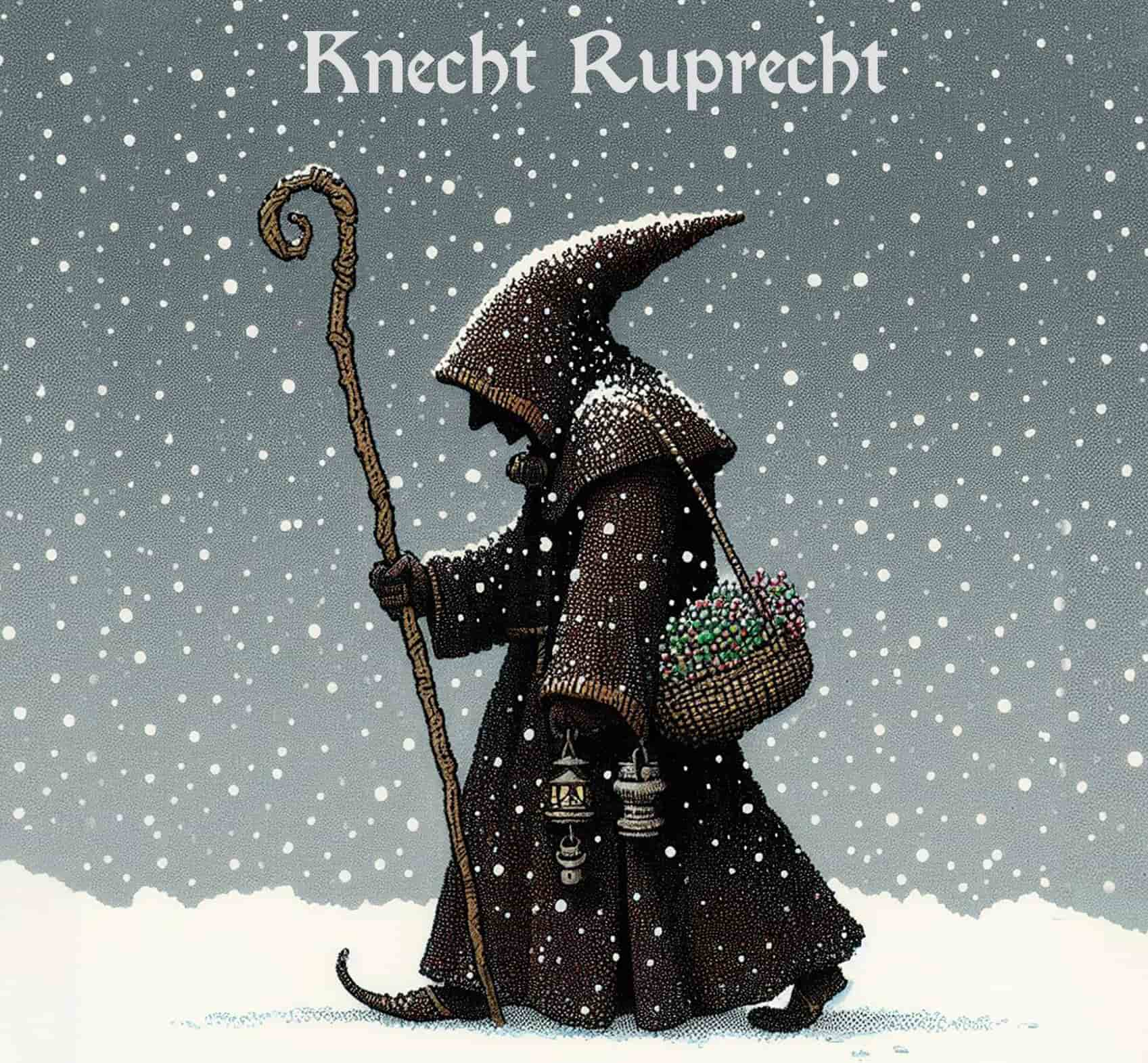

Martin Luther shifted the customary gift-giving, which was previously observed in his household on St. Nicholas Day (there are household records from the Luther residence documenting gifts for servants and children on St. Nicholas Day in the years 1535 and 1536), to Christmas Eve. This change occurred because the Protestant Church did not engage in saint veneration. The new Protestant gift-bearer was no longer St. Nicholas but the “Holy Christ,” as Luther referred to the infant Jesus. From this abstraction, the angelic Christ Child emerged in Thuringia and other regions, appearing in Christmas processions since the 17th century, where Mary, Joseph, and the Jesus Child paraded through the streets—akin to today’s Star Singers—accompanied by white-clad girls with open hair as angels, led by the veiled “Christ Child.” After 1800, Knecht Ruprecht, originally the punishing companion of St. Nicholas and the Christ Child, gradually transformed into Santa Claus.

Santa Claus

According to the German Atlas of Folklore in 1930, Santa Claus (predominantly in the Protestant North and Northeast) and the Christ Child (mainly in the West, South, and Silesia) were the gift-bringers. The demarcation ran between Westphalia and Friesland, Hesse and Lower Saxony, Thuringia and Bavaria, going through southern Thuringia, southern Saxony, and Silesia. In the 18th century, it was different: St. Nicholas delivered gifts in Catholic areas, while the Christ Child did so in Protestant regions. With the increasing popularity of Christmas and the Christ Child, the gift-giving date in Catholic regions shifted from St. Nicholas Day to Christmas Eve, adopting the Christ Child tradition.

Santa Claus is a syncretic figure, blending elements from St. Nicholas, Knecht Ruprecht, and the rough Percht in a demystified form. A drawing by Moritz von Schwind in the Munich Picture Sheet No. 5 from 1848, titled “Herr Winter” – though avoided by people – is considered an early representation, although not the only one. Older descriptions in poetic form come from North America, where he is called Santa Claus. The attire, predominantly depicted as red in Germany after 1945, was adopted from Knecht Ruprecht, and the flowing beard from common depictions of God the Father. In traditions for young children, he brings gifts, but to naughty children, he brings a switch.

Secret Santa and Gift Exchange

The Nordic legendary figure of Nisse (Danish Niels for Nicholas), adapted in German as Wichtel, with its red hat, bears resemblance to Santa Claus. Derived from this is the custom of Secret Santa during the pre-Christmas period, where individuals exchange gifts anonymously in a random pairing of giver and receiver.

Gifts known since ancient times for New Year’s persisted well into the 20th century, locally even until today, as monetary gratuities for mail carriers, newspaper carriers, garbage collectors, etc. According to Börsenblatt, in 2007, one-fifth of intra-family Christmas gifts were passed on in the form of vouchers or cash. However, the tradition of Christmas gift-giving traces back to St. Nicholas gift-giving. “Lüttenweihnachten” refers to decorating a Christmas tree for animals in the forest with feed.

Christmas Singing

In the intimate setting of homes, much singing and musical activity takes place on Christmas Eve and the first and second holidays. In a time of diminishing familiarity with folk songs and hymns, German Christmas carols remain a part of the residual traditional German song repertoire for many people in the German-speaking region, allowing them to join in the singing. In the public sphere, the collective singing of Christmas carols by large groups of people has evolved into a distinct tradition, particularly in Berlin.

Christmas Meals

- Christmas usually involves an elaborate Christmas feast on the first holiday, featuring specific dishes such as Christmas goose or carp, as well as specially crafted Christmas treats like Stollen or regional gingerbread specialties such as Aachener Printen, Nuremberg gingerbread, or Liegnitzer Bombe.

- In some regions, on Christmas Eve, likely for the simplicity of preparation, traditional dishes like stew or sausages with potato salad are served. In the north, the potato salad is prepared with mayonnaise, while in the south, only vinegar, oil, and broth are used. A straightforward dish is associated with the Lower Silesian Christmas, the “Breslauer Mehlkloß” (made from flour, milk, butter, and egg).

- In Altbayern (Old Bavaria), the animal fattened for the Christmas feast, usually a pig or occasionally a Christmas goose, is colloquially referred to as the “Weihnachter.”

- In the Vogtland and the Erzgebirge, the so-called Neunerlei, a Christmas menu with nine courses served on Christmas Eve, is prepared. It typically includes sausages, dumplings, sauerkraut, goose or pork roast, nuts, and mushrooms. In many families, coins are placed under the plates.

Other Christmas Customs in Germany

Among the less reflective Christmas traditions is the telling of traditional spooky stories (sometimes ironic, like snowmen by the campfire, or not, like The Man with the Head Under His Arm), especially while awaiting the gift-giving in the anteroom on Christmas Eve. This seems to be particularly prevalent in North and Northeast Germany. In Alpine traditions in December and January, perchta, figures associated with driving away winter, play a role.

Another custom on Christmas Eve is the “Christklotz” also known as Yule Log. In Berchtesgadener Land (a Bavaria district), the Christmas shooting of the Christmas marksmen marks the last week before Christmas. They shoot every day at 3 o’clock in the afternoon from their positions—additionally on Christmas Eve before the Christmas Mass.

A supposedly old German custom imported from the USA revolves around a Christmas tree decoration in the shape of a pickled cucumber, known as the “Christmas Pickle.” The “Christmas Pickle” is discreetly attached to the Christmas tree before the gift-giving ceremony. The recipients, usually children or teenagers, search the tree for the hidden ornament before opening their presents. The person who finds the “pickle” first receives a special, additional gift. Since 2009, this Christmas tree ornament, resembling spice pickles, has been available at German Christmas markets. Glassblowers offer three different sizes to tailor the difficulty level to the age of the children.

As darkness falls during the Advent season, numerous windows in homes are illuminated by Schwibbögen. This tradition originated in the 18th century in the Ore Mountains mining regions and is increasingly spreading to neighboring countries. Every year, the Deutsche Post issues special stamps for Christmas. In many places, Christmas markets, also known as Christkindlesmarkt or Glühweinmarkt, have become established during the pre-Christmas period. They are characterized by stalls selling Christmas items and gifts, mulled wine stands, and an increasing number of food stations.

Abstention from Christmas Celebrations in Germany

The reformist churches believed that Christmas festivities originated from pagan customs and were associated with the Catholic Church, so they fundamentally rejected them. In 1550, in Geneva, all non-biblical celebrations were banned, leading to severe conflicts. John Calvin was less strict on this matter. In 1560, John Knox prohibited all church festivals, including Christmas, in Scotland.

Scottish Presbyterians adhered to this ban into the 20th century. Quakers and Puritans of the 17th century also rejected Christmas as a holiday and continued with their usual activities. In that period, the English Christmas celebration included not only church services but also feasting, revelry, dancing, and gambling. In 1647, Parliament enacted a ban on such festivities, leading to street riots between supporters and opponents of Christmas. After 1660, the ban on celebrations was no longer enforced.

Only in recent times have regulations adapted to the behavioral patterns of their cultural surroundings. In the 19th century, Christmas saw a significant resurgence in England, possibly influenced by Prince Albert from Germany, whom Queen Victoria had married. The development in the USA followed a similar trajectory. In regions where predominantly Presbyterians, Mennonites, Quakers, and Puritans lived (New England, Pennsylvania), there was no Christmas celebration until the 19th century. In the southern regions, English settlers retained their Anglican customs from the 17th century. Dutch settlers brought their Sinterklaas (St. Nicholas) to New York, later evolving into Santa Claus.

-> See also: Jehovah’s Witnesses do not celebrate the Christmas festival.

Adoption of Christmas Customs by Non-Christians

Judaism

In some Jewish households living as a minority in a Christian environment, there is a phenomenon called “Chrismukkah,” where, for example, Christmas trees are set up in living rooms and adorned with balls engraved with the Star of David during the Hanukkah festival.

Islam

In some Muslim households, a goose may be placed on the table for Christmas, and children receive gifts. As the birth of Jesus Christ is extensively described in the Quran, Muslims are not unfamiliar with the origin of the Christmas festival.

Shift of Christmas Customs to the Advent Season

A noticeable change in customs has been observed in the Advent season since the 20th century. Originally observed as a period of fasting, contemporary practices of the Christmas festival are already being embraced in the Advent season. One significant aspect of this is the prevalence of Christmas markets in most German-speaking city centers, some of which have traditions dating back to the Middle Ages.

Christmas in German: “Weihnachten”

In its original form, Christmas is called “Weihnachten” in German which means “the holy nights” in old Germanic. The customary celebration lasted for twelve days, which is why the phrase is plural. Now it’s running in Germany from the evening of December 24th through the 26th.