The heater shield, known for its triangular shape that tapers towards the bottom, holds great significance as the pioneering shield design during the era of living heraldry in the Middle Ages. Referred to as “scutum triangulare” in Latin, “écu triangulaire” in French, “Dreieckschild” in German, and “gotický štít” in Slovak, this cold weapon exemplified the beginning of a new chapter in the art of shields as it often symbolized the spirit of creativity. The first heater shield came together in the 12th and 13th centuries.

The Heater Shield’s History and Origin

The heater shield was first designed during the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries. The shield gets its name because of its resemblance to a clothes iron. Later variations included curvier edges.

It was both a combat shield of military and heraldic significance. Apart from the Low Countries (Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg), the heater shield was the prevailing shield style employed throughout Western Europe.

Historically, this shield appeared almost exclusively in the heraldry of ancient aristocratic houses. Other aristocratic households then adopted it, and occasionally ordinary people did as well.

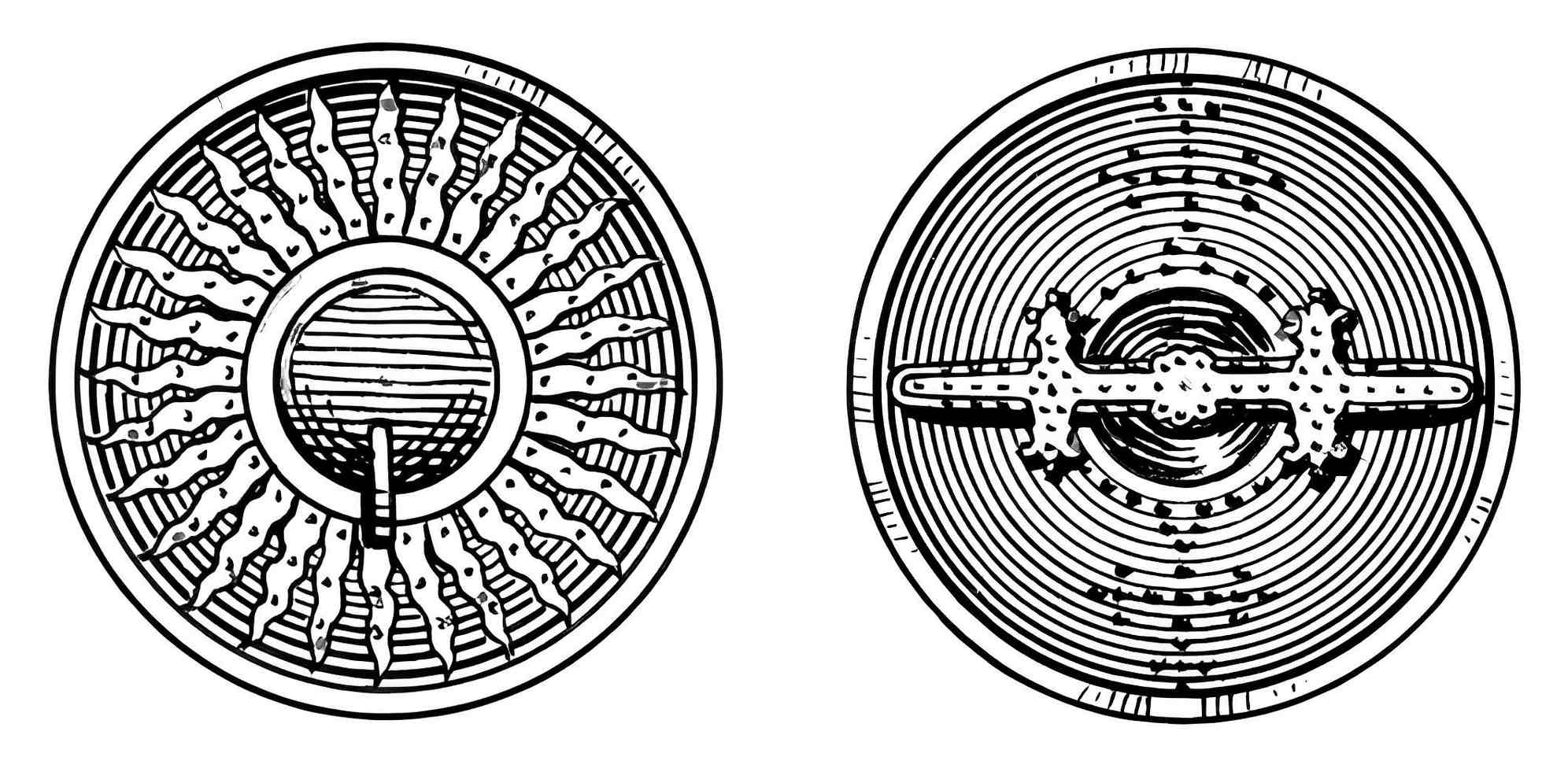

Before the heater shield, the round shield stood as the oldest heraldic shield form. Next came the kite shield or almond-shaped shield, which can be seen on the seals of the Counts of Arnsberg between the years 1200 and 1300.

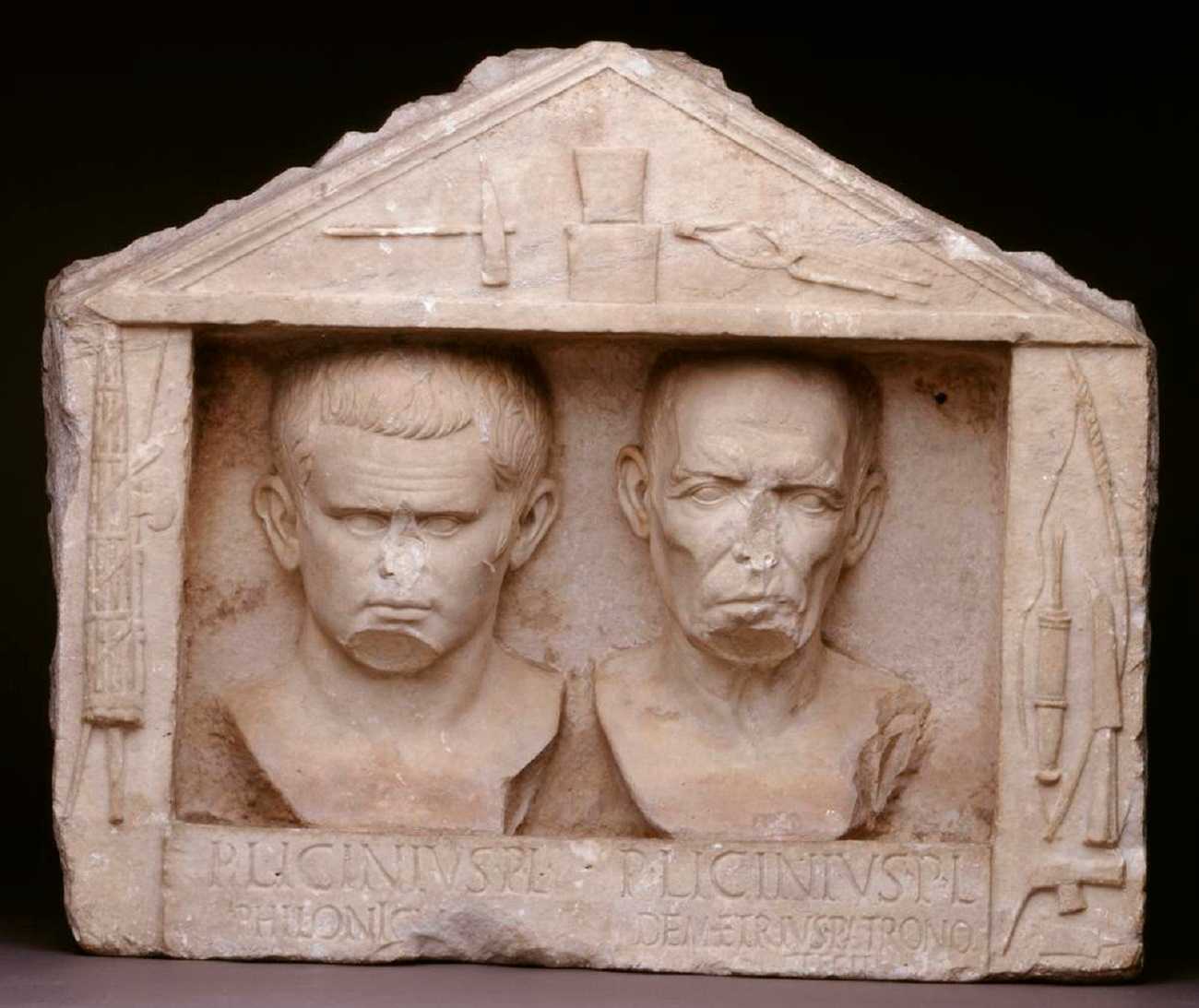

But this shield was most commonly associated with the seals of high priests and churches between the years 1140 and 1300 (as seen below), as well as the seals of aristocratic ladies during this time.

In the 12th century, two distinct shield designs stood out the most compared to others: the heart-shaped shield and the almond-shaped kite shield. At the end of the 12th century in France, these two designs evolved into a large heater shield with rounded corners.

Until that point, the Norman kite shield had retained some features from its pre-heraldic era origins. This type of shield was used, for example, by Henry III, Count of Brabant (1086), Godfrey I, Duke of Brabant (1110–1151), Philip and Theodoric, Counts of Flanders (1161), Theodoric, Count of Holland (1190–1201), Philip, Count of Namur (1206), Henry, Count of Lotharingia (1220), Theodoric, Lord of Malberg (1233), and many other nobles and dynasties.

The Rise of the Heater Shield

The heart-shaped shield was one of the oldest heraldic shields and it can be found on the seal of Robert de Chartres (1193), a French noble. This form was in use until the first quarter of the 13th century, as seen on the seal of Raoul de Gif in 1228 when the elongated form of this shield also appeared.

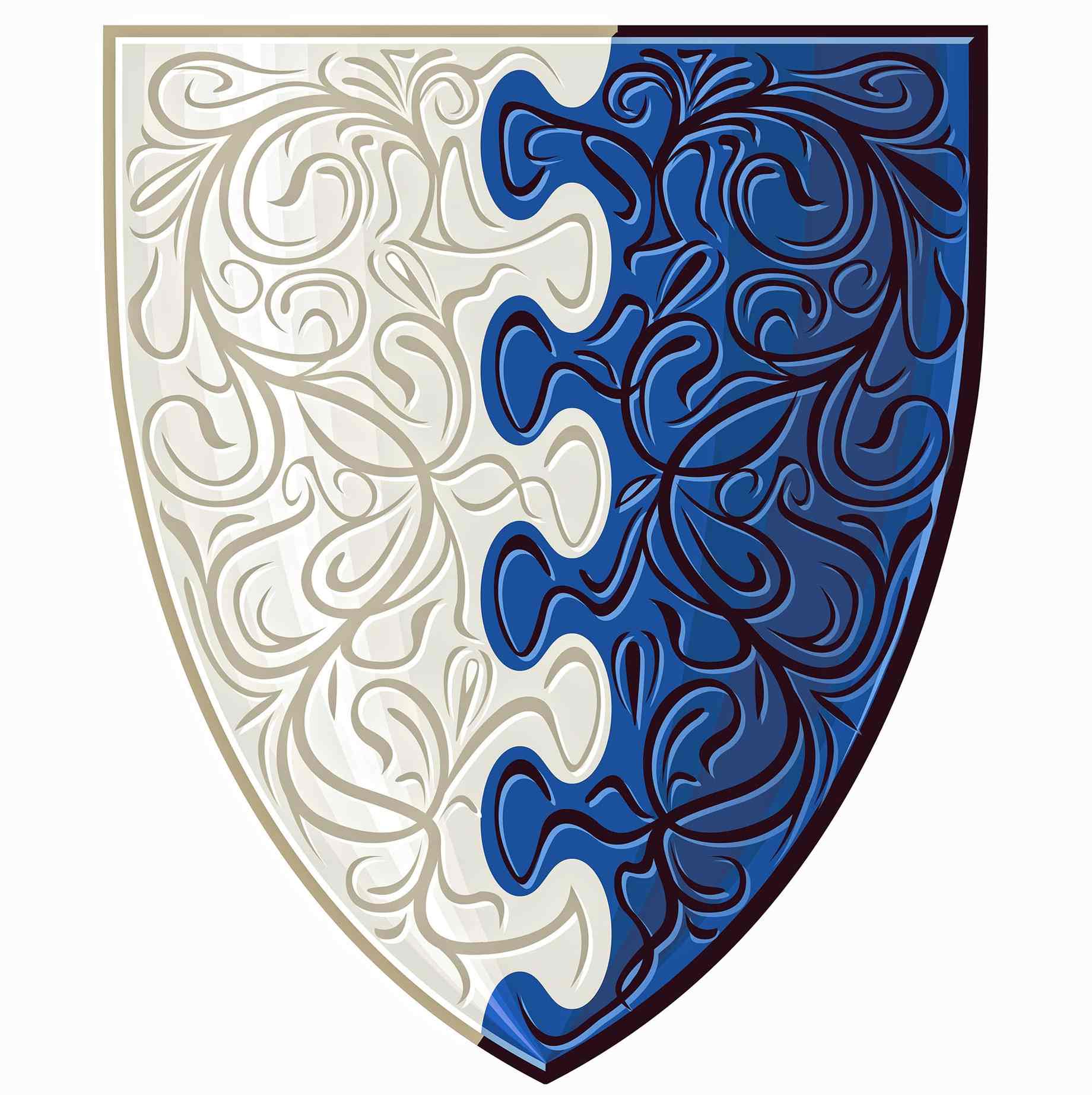

However, by the 13th or 14th century, the heater shields had superseded it as the preferred design. Henry I, Duke of Lorraine (1195), William, Count of Holland (1213), Henry, Duke of Lorraine (1241), and Henry, Lord of Reifferscheid (1254) were the first to employ heater shields with recurved sides. They became known as the Manesse form (see the below image).

Other people around the same time also used straight-sided heater shields, such as Theodoric, Count of Holland (1199), and Albert of Habsburg (1206).

The size of heater shields began shrinking dramatically in the middle of the 13th century, and this trend accelerated after the middle of the century.

The upper portion of these shields tended to have relatively straight sides, but by the second half of the 13th century, it was not uncommon to find heater shields with concave edges, giving rise to the “classic” heater shield design.

This form of shield was used by William, Count of Holland (1205), Florian IV, Count of the Netherlands (1232), Henry, Duke of Lorraine and Brabant (1241–1253), Baldwin, Count of Bentheim (1246), Rausseman von Kempenich (1251), Gerard, Lord of Wildenberg (1267), Godfrey of Brabant (1284), Gérard, Lord of Voorne.

The Oldest Coat of Arms on a Shield

Thus, the enormous Norman kite shield was shortened to form the modern heater shield. Its straight top edge contrasted with its somewhat rounded edges.

The earliest heraldic examples of this shield appear on Gothic shields. Thus, the oldest coat of arms on a shield in history is actually the heater shield, which has a length-to-width ratio of 8:7.

According to the Oxford Guide to Heraldry (2001), it is an azure shield with four gold lions rampant, which King Henry I of England is rumored to have given to his son-in-law, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, in 1127 AD.

His shield supports a shield boss, and it looks like a kite shield at first glance. But it has a straight top edge and a triangular body rather than an oval top edge and oval body design.

The Heater Shield Got Smaller and Smaller

During the 12th century and the first two-thirds of the 13th century, heater shields continued to be enormous in size, measuring roughly half a man’s height. As a result, it was worn over one shoulder with a strap and encircled half of the wearer’s body.

They were only half as tall as men until the end of the 13th century, and just a third as tall until the middle of the 14th. Beginning in the second part of the 13th century and continuing throughout the 14th century, it shrank and gradually took on the form of an almost isosceles triangle with slightly curved outward edges. As the 14th century came to a close, the heater shield was no longer used in battle.

Beginning in the early 13th century, as shown on the shields in the Codex Manesse (c. 1304), a variant of the heater shield appeared with sharply rounded sides. Compared to the heater shields used in the middle of the 13th century, this variant was tiny.

The heater shield, along with variants with rounded sides, is still a widely used design today in both military and popular culture. Although heater shields became less common in the 14th century, they still occasionally appeared on seals and gravestones at the start of the 15th century. Some heater shields even had spikes on them.

References

- Living Heraldry: The Ancient Art and Its Modern Applications – Stephen Slater, 2004 – Google Books

- The Oxford Guide to Heraldry – Thomas Woodcock, John Martin Robinson, 2001 – Google Books