The July Monarchy was a constitutional and liberal monarchy arising from the revolutionary days known as the Three Glorious Days (July 27, 28, and 30, 1830), which led to the abdication of Charles X and the proclamation of Louis Philippe I as the King of the French. Favorable to business interests, this new regime is traditionally considered the triumph of the bourgeoisie.

- Louis Philippe I: The ” Enlightened ” Prince of the Future July Monarchy

- Charles X’s Difficult Succession

- Louis Philippe I’s Accession to the Throne

- The Constitutional Charter of the July Monarchy

- An Ambitious Foreign Policy

- Education and the Church

- Major Works Policy and the Art World

- Government Action

- Crisis of Regime and End of the July Monarchy

On the international front, the July Monarchy sought peace through a policy of amicable understanding with Great Britain while revitalizing the French colonial empire through a new policy of conquests (North Africa, Black Africa, the Far East, and the Pacific). Becoming authoritarian and reactionary, it was overthrown by the February 1848 revolution.

—>Louis-Philippe adopted the title of the “Citizen King” to emphasize his ties to the July Revolution and his commitment to a more liberal and constitutional form of monarchy.

Louis Philippe I: The ” Enlightened ” Prince of the Future July Monarchy

Louis Philippe I was born in Paris on October 6, 1753. He descended from the Capetians through his father, the Duke of Burgundy, Louis Philippe I, and his mother, Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon, the daughter of the Count of Toulouse, himself a descendant of Louis XIV. Titled Duke of Valois and later Duke of Chartres in 1785, his education was overseen by the Countess de Genlis, who was dedicated to providing him with an extensive education in the spirit of the Enlightenment. In 1789, the young prince was swept up in revolutionary enthusiasm, even joining the Jacobin Club. He participated in the early battles of the revolutionary army but, disheartened by the deadly wave of the Reign of Terror, he betrayed the revolutionary ideal.

In 1793, following the execution of his father, Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, he sought refuge in Switzerland, America, Sweden, Germany, and England. Taking refuge in Sicily in 1809, he married Princess Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily (Marie-Amélie de Bourbon). Successful in his attempts at reconciliation with Louis XVIII in 1814, it was not until 1817 that the prince, now Duke of Orléans, emerged from his extended exile. Throughout this period, he consistently opposed his cousin’s policies and assumed the role of the liberals’ emissary.

Charles X’s Difficult Succession

After the publication of the Four Ordinances of Saint-Cloud and the uprising of the people of Paris during the July Revolution, King Charles X was compelled to abdicate at Rambouillet. Concerned about securing the dynastic succession within his lineage, he persuaded his son, the Duke of Angoulême and Dauphin of France, to forgo his accession to the throne in favor of his grandson, the Duke of Bordeaux.

The Dauphin, under the name Louis XIX, thus reigned for only a few minutes, and the Duke of Bordeaux, now the claimant to the throne as Henry V and titled Count of Chambord, only succeeded in asserting himself in the eyes of the legitimists. The dynastic succession, as envisioned by King Charles X, planned to appoint the Duke of Orléans as regent of the kingdom.

—>The July Ordinances were a series of decrees issued by Charles X in July 1830, restricting civil liberties and dissolving the Chamber of Deputies. These ordinances triggered the July Revolution.

Louis Philippe I’s Accession to the Throne

During the 1830 revolution, a faction of the bourgeoisie chose to ensure the continuity of power by supporting Prince Louis-Philippe, who was also a descendant of the Capetians. Although the idea of establishing a republic was entertained, the lingering memory of the Terror prompted royalists and liberals to promptly agree on forming a liberal parliamentary monarchy. As a result, many republicans, overlooking Charles X’s abdication text, proposed the general lieutenancy of the kingdom to the Duke of Orléans.

The prince, sensing the tide turning in his favor, hesitated to accept the succession offered by Charles X. On July 31, Louis-Philippe was introduced to the Parisians, and on August 7, 1830, following the favorable votes of the deputies and peers constituting the two parliamentary chambers, he officially became Louis-Philippe I, King of the French. He swore allegiance to the new constitution and pledged to remain faithful to the Constitutional Charter of 1814, albeit somewhat modified by Parliament.

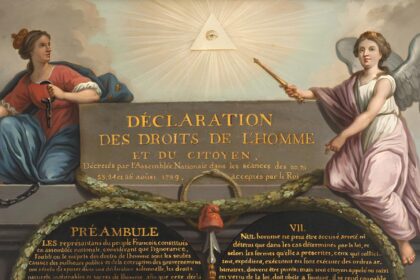

The Constitutional Charter of the July Monarchy

After the July Revolution, the governmental system of the Constitutional Charter of 1814 was extended. Louis-Philippe, relying on the ambition of politicians, utilized the new electoral system based on property qualifications to consolidate his power. France witnessed a strengthening of the representative system, evolving into a parliamentary regime. The kingdom also benefited from economic development, influenced by the early stages of the Industrial Revolution.

The Constitutional Charter divided the Parliament into two chambers: the Chamber of Deputies, elected for five years through property-based suffrage, and the Chamber of Peers, whose assembly, hereditary at first, was later renewed by the king. However, the law of December 29, 1831, eliminated royal appointments to the peerage. Consequently, the upper chamber lost its significant political role.

Furthermore, deputies sought to amend rules governing voting access, property qualifications, and eligibility conditions for candidacy. On April 19, 1831, a law reduced the annual property qualification and lowered the minimum voting age.

Some liberal opponents accused the sovereign of implementing a conservative policy contrary to liberal principles and reform, while he was, in essence, skillfully adhering to the principles and rights outlined in the Constitutional Charter. When inheriting the throne, Louis Philippe I aimed to exercise the full extent of royal prerogatives.

To achieve his goals, he exploited the intrinsic weaknesses of the parliamentary system. On several occasions, the king exercised his right to dissolve the Chamber to ultimately secure a majority of deputies favorable to his policies. Additionally, faced with the monarch’s strong will, most Prime Ministers hesitated to resist.

An Ambitious Foreign Policy

The sovereigns of Europe reluctantly accepted the establishment of the July Monarchy. Louis Philippe I, despite the discontent of the French people nostalgic for the victorious Napoleonic campaigns, successfully maintained peace beyond his borders. In 1831, the king rejected the throne of Belgium on behalf of his son, the Duke of Nemours, but nonetheless approved the marriage of his daughter Louise to Leopold of Belgium in 1832.

French forces became involved in restoring peace in Portugal, participating in conflicts in Mexico and Argentina. France occupies the Marquesas Islands and engages in commercial activities with China. The alliance with England did not diminish the commercial and political rivalry between the kingdoms of France and Great Britain in Spain, Greece, and the Ottoman Empire.

In 1845, a treaty abolished the slave trade. Meanwhile, France expanded its colonial influence in Africa. The occupation of Algeria and Morocco intensified, culminating in the surrender of Emir Abdelkader to the Duke of Aumale in 1847.

Education and the Church

The Law of June 28, 1833, entrusts secular authorities with the responsibility for primary education, diminishing the role of the Church. Although schooling is not yet compulsory, government provisions aim, on the whole, to facilitate access to education for the middle class. The educational system is highly diversified, lacking specialization, ensuring that positions within the state are not reserved for a privileged class.

In 1842, the government even legislated on child labor in factories. Under the influence of republicans, the July Monarchy proclaims the secular nature of the state, allowing the sovereign to break free from the influence of the church and make substantial economic savings.

Major Works Policy and the Art World

Public utility works are undertaken or completed, such as the Arc de Triomphe, the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madelein, or the City Hall of Paris. The Palace of Versailles was transformed into a national museum aimed at showcasing the significant military and political events in French history. Napoleon Bonaparte‘s remains are ceremoniously interred at Les Invalides. Additionally, extensive railway lines started to be constructed to connect the major cities in France.

During the July Monarchy, Romanticism served as the primary inspiration for the great innovators in the worlds of arts and letters. Romantic art elevated lithography to the forefront, and the realm of painting was undeniably dominated by Eugène Delacroix. Concurrently, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres perpetuated the tradition of historical painting and portraiture.

Government Action

The gap was significant between Paris and the provinces, between those nostalgic for yesterday’s privileges and the beneficiaries of new regimes. Positioned between parties with often extreme positions, Louis Philippe I was compelled to adopt a moderate and liberal policy, partially reconciling Republicans, monarchists, legitimists, and Bonapartists.

Through his compromises, political reversals, and the revolts plotted against him, the king appointed the banker Jacques Laffite as the President of the Council. Faced with Republican opposition, the king then reversed course by appointing Casimir Perier as the head of the government in 1831, followed by the Duke of Dalmatia, Marshal Nicolas Soult.

The government legislates on crucial matters such as freedom of the press, the reform of the penal code, the suppression of the slave trade and the liberation of slaves, the abolition of gambling houses and lotteries, and the recruitment of the army. However, the economic crisis, weakening the kingdom from 1845 onwards, suddenly put a brake on legislative reforms and the liberalization of the country.

The agricultural crisis of 1846–1847 left rural and working populations weakened and discontented. Opposition becomes increasingly assertive, and the aging king must contend with the proliferation of attacks. Prime Ministers succeeded each other rapidly, including the ministry of Marshal Soult, the cabinets of the historian and journalist Adolphe Thiers, Count Louis-Matthieu Molé, and François Guizot.

Crisis of Regime and End of the July Monarchy

The system of parliamentary monarchy, characteristic of the July Monarchy, was gradually weakened by internal conflicts and the chronic instability of the French executive. The instability primarily stems from persistent personal disputes, much less than the prohibition of a radical banquet and the repression carried out in the capital. The government of François Guizot was compelled to resign. The revolution spreads throughout Paris, and the king, faced with the need to appease the people, chooses to abdicate rather than order the crowd to be fired upon.

In his act of abdication, Louis Philippe I designated his grandson Henry, Count of Paris, as the dynastic heir, while the Duchess of Orléans became regent of the kingdom. However, the republicans, determined to seize power, established a provisional government. Alphonse de Lamartine and Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin proclaim the advent of the French Second Republic.

Faced with opponents of his regime, the king decides to go into exile. He flees to England, where Queen Victoria diplomatically provides him with Claremont Castle, where he assumes the title of Count of Neuilly. On August 26, 1850, the elderly monarch died at the age of 77.