Louise of Lorraine-Vaudémont was the last Queen of France from 1575 to 1589, during the Valois era, without offspring. Her marriage to Henry III was the only one not arranged for political reasons, but inspired by a “true and sincere inclination.” Gentle, beautiful, unpretentious, without fortune, and an ally of Catherine de’ Medici, she was an ideal queen with a sovereign’s behavior. She is the only queen to actually rest in the tomb bearing her name at Saint-Denis!

Louise of Lorraine: A Wife for Henry III

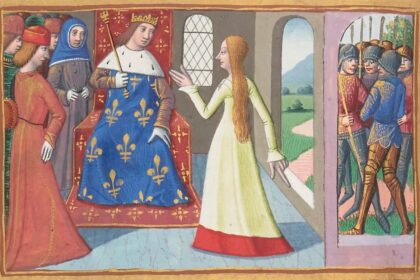

Upon the death of Marie of Cleves, Henry’s youthful love, the young king was prostrate, exhibiting macabre behavior (his clothes bore skull emblems), experiencing mystical crises, and following penitent processions. Catherine de’ Medici urgently needed to marry him off and proposed several candidates: Doña Juana, Philip II’s sister; Mary Stuart, widow of Francis II; his sister-in-law Elizabeth, widow of Charles IX; and the Queen of England, of whom Henry had a strong opinion: “she’s an old creature with a bad leg.”

To cut short other proposals (a Swedish or Danish princess), the king declared his choice was made: it would be Louise of Vaudémont!

A Discreet Lady

Born in April 1553 to Nicolas of Mercœur, Count of Vaudémont, belonging to the cadet branch of the House of Lorraine, Louise, cousin of the Guises, was the eldest of fourteen children and only a year old when her mother, Margaret of Egmont, died. Nicolas of Mercœur’s second wife, Jeanne of Savoy-Nemours, was affectionate and introduced her to the court of Nancy when Louise was ten.

Catherine of Aumale, her father’s third wife, was harsh and jealous, but Louise could count on the friendship of Claude, Catherine de’ Medici and Henry II’s second daughter.

Tall, blonde, of delicate beauty, and discreet, Henry had met her in Lorraine when he was leaving for Krakow. She had moved him with her modesty and gentleness. She may have been a young woman without rank, fortune, or pretensions, but “he wanted to take a wife of his nation who was beautiful and agreeable, saying he desired one to love well and have children with, without going to seek others from afar, as his predecessors had done.” Catherine de’ Medici loved her son so much that she approved!

She was won over by “the gentle and devout spirit of this princess whom she judged more suited and inclined to pray to God than to meddle in affairs.”

As for Louise, she renounced two suitors (François of Luxembourg and the Count of Salm), and the king offered one of them his current mistress, the lady of Châteauneuf!

A Non-Political Marriage…

Louise’s father gave his consent very quickly, and in a month, “everything was settled”: the king arrived in Reims on February 11, was crowned on the 13th, and the wedding took place on February 15, 1575! Louise was radiant with joy, the king’s heart melted with tenderness. They entered the capital, and she was Queen of France!

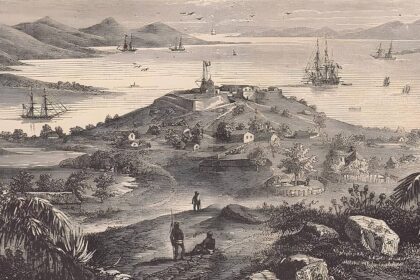

From that day on, Louise never changed her attitude and remained dazzled and amazed. Her love for her husband would withstand time, trials, infidelities, and death! Occupying little space, she blended into the king’s entourage, always by his side at all ceremonies, all festivals, all feasts. She was associated with the creation of the Order of the Holy Spirit (the insignia bore their initials). Etiquette required the king to pay her a daily visit, but he did more: they went for walks in Paris, visited monasteries, discovered the sea in Normandy, the port of Dieppe, and stayed on the land of Ollainville (a castle the king gave her and had renovated).

All these attentions lasted well beyond the honeymoon: in 1581, she was seen sitting on the king’s lap; in 1587, he “spent almost the whole day with her and tried with words full of affection to exhort her to keep courage” when she was seized with a tertian fever; like Francis I, the king did not officially introduce a royal mistress, as Louise meant a lot to him.

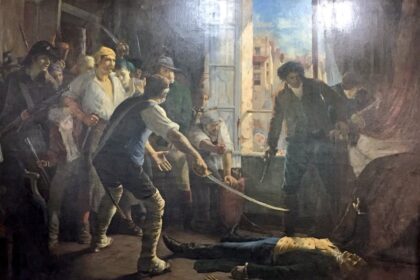

Yet not everything was “rosy.” The king had a mistress, a lady advised Louise to take a lover: she was chased away! A conspiracy was led by one of the king’s favorites who entered the queen’s chamber, the favorite became Henry’s nemesis, and the affair turned into a matter of state! But this strengthened the bonds between the king and queen, as Louise had the qualities of a queen of the time: piety, discretion, obedience, love for the monarch…

Brantôme recounted, “One can and must praise this princess for much; for in her marriage, she behaved with the king her husband as wisely, chastely, and loyally as the knot by which she was bound in conjunction with him always remained so firm and indissoluble that it was never found undone or untied, even though the king her husband loved and sometimes went to change”; “She devoted herself to nothing else but serving God, going to devotions, continually visiting hospitals, tending to the sick, burying the dead.”

…But No Children

She participated in a procession in penitent costume, hoping for a child! For from the beginning of their union, she wished to offer a dauphin to the king. Unfortunately, the couple was and remained childless, many thinking it was due to the king’s sterility (because of his inclinations). They had themselves examined, called upon potion “makers,” went to thermal cures, the king engaged in prayers and devotional gestures, he undertook pilgrimages from 1580 to 1586, she did not adhere to her husband’s mystical sessions, she tried to understand him, to help him, but did not approve.

The couple remained united and supportive, but they were resigned, they would not have children: God willed it so.

A Precious Support

An irreproachable Catholic, she devoted herself to the poor, orphans, and prisoners. She patronized a Charity House in the Mouffetard district. She is also credited with bringing light to crossroads, thanks to statues of the Madonna illuminated by a lamp. Her popularity increased when in 1586 she allocated an annuity to two students so that “they ensure the preaching on Sundays and annual feasts in the prisons of the Conciergerie, the grand and petit Châtelet of Paris.”

During the troubles of the League, she supported her husband against her Lorraine family: it was an act of honor. She even went so far as to reproach him for rebelling! When the king decided to arrest the Duke of Guise, she approved; during the days of the barricades, cloistered in Paris, she faced the Duke of Guise alone; she supported her husband when he decided on the death of his enemy; she was still by his side for the meeting at Plessis-lès-Tours.

But on August 4, 1589, she received a last letter: the king had just been the victim of an attack, and wanted to reassure her “My love, I hope I will be very well; pray to God for me and do not move from there.”

She Mourned But Did Not Forgive!

Louise took on white mourning, settled in Chenonceau in a room facing the river, and organized her life: walks, embroidery, reading of the Lives of Saints, Sunday service in the small church of Francueil. In her room, there were mementos of her husband everywhere: a portrait on the fireplace with the motto “saevi monumenta doloris,” flaming torches, widow’s cords, all on a black velvet background.

She did not forgive those who had killed her husband and “desires no more life than to see punishment done to those who make it so miserable for her.” Only half satisfied when the prior of the convent to which Jacques Clément belonged was sentenced to death, and because the Guises were responsible, she appealed to Henry IV: he evaded the question and absolved the Duke of Mayenne and the Lorraine princesses in 1596!

She would never forgive! She begged the pope for the Church to make amends for all that had been done against the king, and many years later, finally, the pope annulled the excommunication and proclaimed Henry III dead in peace with the Church.

Louise of Lorraine at Saint-Denis

But Louise was tired and worn out by this struggle. She received a final blow: she had to leave Chenonceau! Catherine de’ Medici’s will presenting more liabilities than assets, Louise would have to pay her share of her mother-in-law’s debts if she wanted to keep the castle, which was impossible!

The estate was sold at auction in December 1593; Louise’s half-brother, a Mercœur, bought back Chenonceau, left it to Louise, but charged her with donating it to the young future spouses: Mercœur’s only daughter and little César (who had just been born), son of Henry IV and Gabrielle d’Estrées. She had the usufruct, but preferred to leave these places of sorrow and settled in the Duchy of Bourbonnais, in Moulins. She died at the end of January 1601, after catching a cold in a church during a sermon the previous December.

She is the only queen to actually rest in the tomb bearing her name at Saint-Denis: she was first installed in the Capuchin convent in the Faubourg Saint-Honoré, then in the new Capuchin church near Place Vendôme, was transported to Père Lachaise during the Revolution, and accessed Saint-Denis in 1817. While all the kings’ tombs had been violated and the remains thrown into the common grave!