From 1792 to 1815, France experienced over twenty years of nearly unbroken warfare. The Empire, in this regard, merely continued the French Revolution, though it diverged in other respects. In this context, the daily life of Napoleon’s soldier took on particular importance and significance. More than a million soldiers had to be recruited, clothed, fed, and armed.

How did the Emperor overcome the challenges he faced? What were the reactions of the population and the army? How can we explain that in 1815, despite the sacrifices and hardships endured, so many men once again rallied to the imperial regime? These are some of the questions we will attempt to answer.

What Role Did Conscription Play in Napoleon’s Army?

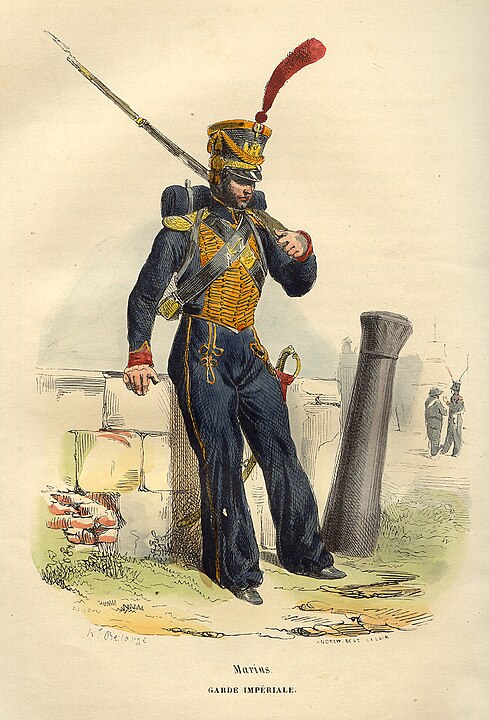

Napoleon’s Soldier

From the moment he came to power, Napoleon Bonaparte had considered drawing from the reserves found in orphanages, but the mortality rate there was so high that he had to abandon the idea. The imperial soldier was therefore recruited through conscription; legislation since 1796 mandated that every Frenchman aged 20 to 25 was required to perform military service.

During the relatively peaceful period of the Consulate, the First Consul endeared himself to the wealthier classes by allowing substitution: those called up could avoid their military obligations by purchasing a substitute, provided the replacement did not come from the reserves. This unequal arrangement primarily filled the ranks with men from the lower classes, creating a divide in the burden of service.

The long period of war that began after the break in the Treaty of Amiens created recruitment difficulties, which led Napoleon to bypass the laws. He began calling up classes early and incorporating young men from previous classes who had been exempt from military obligations. An article was introduced into the imperial catechism threatening Christians who refused to serve with damnation. Schoolchildren were placed under military supervision and given uniforms to instill discipline and a military spirit in them.

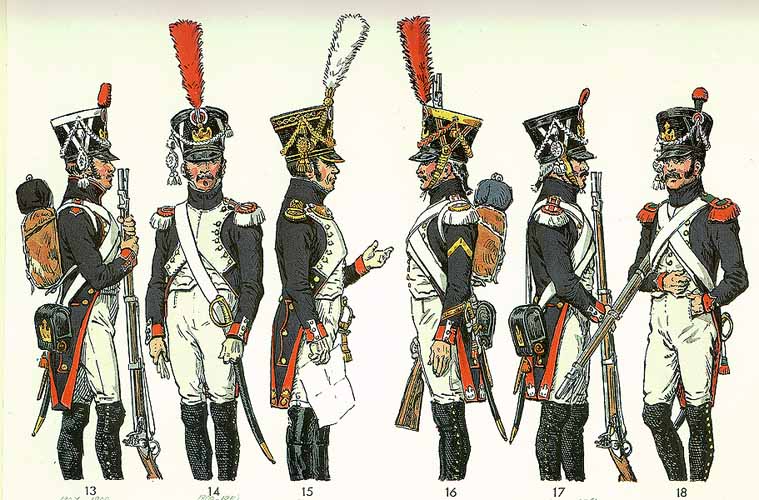

The conditions for exemptions were tightened so that individuals previously deemed unfit were enlisted, with the weakest assigned to the role of nurses. After the disastrous Russian campaign, the creation of the Guards of Honor forced young men from wealthy classes to serve the Emperor, tying their fate to that of the regime. By 1813, many recruits were barely out of childhood, and they were referred to as “Marie-Louises” in reference to the Empress.

During the Empire’s early campaigns, the issue of military training did not arise, as the army largely consisted of soldiers who had been fighting for over a decade. However, as time passed and battles thinned the ranks of veterans, the training of recruits became increasingly problematic, leading to frequent accidents.

During the German campaign in 1813, for example, Napoleon suspected that many soldiers who had injured their hands while loading their rifles had done so intentionally to avoid service. He considered decimating them but was persuaded otherwise by Larrey, the famous surgeon, who demonstrated that the injuries were accidental and caused solely by the conscripts’ incompetence. The Emperor was grateful for his candor, which had spared innocent men from being condemned to death.

A Recruitment Increasingly Problematic

Over time, the high proportion of inexperienced soldiers forced the Emperor to adapt his tactics. To reinforce the sense of security and cohesion among the troops, who had become less maneuverable, he increasingly resorted to using massive formations. These compact masses had the advantage of acting like battering rams to break through the enemy’s front lines, but at the same time, they offered the enemy perfect targets, with each cannonball from their artillery wiping out entire rows. This is why the battles of Eylau, Wagram, and the Moskow were much deadlier than that of Austerlitz, without achieving equally decisive results.

From the beginning of the Empire until its fall, no victory was ever capable of leading to peace, as England remained out of reach. Victories never resulted in more than fragile truces. However, the enormous consumption of men that these perpetual conflicts demanded wore down the country. Draft evaders were increasingly numerous. Some young men even went as far as having all their teeth pulled out, making themselves ill, or faking deformities to escape conscription. Prefects received strict orders; the parents of deserters were heavily fined.

These measures had no effect. By 1813, Napoleon himself estimated the number of draft dodgers at 100,000, and this number was likely much higher. The population was turning away from the regime at a time when it was crucial to rekindle the revolutionary fervor of the soldiers of the Year II. The enormous death tolls partly explained this shift: over 450,000 dead in Spain, at least 80% of them French, more than 300,000 in Russia, around 200,000 of whom were French, to mention only those losses. Another cause of the public’s disaffection was the dispute with the Pope, which disoriented a largely Catholic population, and the invasion of Spain, with which regions of France, particularly Auvergne, had close ties due to traditional economic migration.

1.6 Million Draftees Under Napoleon

During his reign, Napoleon called more than 1.6 million Frenchmen to the colors. Clothing, feeding, shoeing, and arming so many men was no small feat. General Bonaparte believed that war should sustain war, with troops supplying themselves from the field. However, this principle could not be applied in all parts of Europe.

The Emperor knew this and was not disinterested in supply issues; quite the opposite. Orders for setting up mills to grind grain, building ovens to bake bread—documents that have come down to us—attest to how carefully he addressed the vital problem of provisioning the Grande Armée (The Great Army). During the invasion of Russia, the army was accompanied by herds of livestock and numerous supply wagons, but unfortunately, they couldn’t keep up!

Logistics failed to obey the master’s will. Suppliers often lacked honesty: the soles of shoes were sometimes little better than cardboard, and those wearing these carnival shoes soon found themselves walking on the balls of their feet! Pay was irregularly distributed, especially in regions like Spain and Portugal, where guerrilla warfare disrupted communications.

Shortages often forced soldiers to resort to looting. In regions they passed through, even those considered friendly, like Poland, residents hid their provisions for fear of being stripped of their last resources. During the 1807 campaign, soldiers demanded bread in Polish from Napoleon (“tata, chleba”), and he responded in the same language that he had none (“chleba, nie ma”).

In Portugal, in 1811, famine forced Masséna to retreat back to Spain in a hurry, with an army severely reduced by malnutrition and desertion. In Spain, soldiers resorted to eating acorns and vetch while Marmont feasted openly from silverware in front of his starving troops! Looting obviously weakened discipline and exposed those engaging in it to guerrilla attacks. During the march through Poland and then Russia in 1812, soldiers were reduced to eating tough, salted meat that had been preserved for several years, nearly spoiled, and drinking from puddles contaminated with horse urine. Requisitions were insufficient, and the army became disorganized, with disorder leading to waste.

Logistics Struggling to Keep Up

Davout was the only marshal who, by maintaining strict discipline within his corps, managed to supply his troops more or less adequately. Additionally, the privileges enjoyed by the Imperial Guard deprived other units of food and equipment that would have been theirs if the distribution had been fair. The Grande Armée dwindled as it advanced, so that by the eve of the Battle of Borodino, it numbered only 120,000 to 130,000 soldiers, out of the more than 500,000 who had crossed the Niemen. It is true that part of its forces had been left behind to guard the flanks and rear, but the loss was still considerable.

The Napoleonic soldier spent readily without thinking about tomorrow. When he reached a cellar, instead of drawing wine from taps, he would shoot holes in the barrels to sample all the wine. What did it matter what remained for those who followed, as long as he could drink the best! On the eve of a battle, he discarded anything that might hinder him during the fight, so that the morning before an engagement, the bivouac ground was strewn with random objects, as if a tornado had passed through. It was easy to re-equip oneself with the belongings of the dead after victory!

An Army of Marchers

During the Italian campaign, it was said that Bonaparte won battles with the legs of his soldiers. Speed continued to play a decisive role in imperial strategy. The goal was to arrive quickly where one was not expected and to gather maximum forces to overwhelm a disoriented enemy. The Battle of Marengo was won through Desaix’s unexpected arrival on the battlefield just when the Austrians thought the day was theirs.

Conversely, the Battle of Waterloo was lost because Grouchy failed to arrive on time. The infantry covered long distances, usually around forty kilometers a day, but sometimes as much as sixty to seventy kilometers, burdened like mules with a heavy rifle and an array of gear (haversack, blanket, cartridge box, ammunition, food, spare shirts, and shoes…).

The march was so grueling that the bones of the weakest soldiers’ feet would break. To move faster without tiring the infantry, carts were sometimes requisitioned from peasants, but this was rarely possible outside of France. In warring countries, peasants would flee with their animals into the forests at the approach of troops. The abandoned houses, left to an unruly soldiery, were then looted and sacked. Conditions were sometimes so dreadful that soldiers murmured in discontent, leading to the nickname “grognards” (grumblers) during the Polish campaign of 1807.

In Spain, during the pursuit of the English army in 1808 through the Sierra de Guadarrama, these grognards, frozen and exhausted, encouraged each other to shoot Napoleon. The Emperor heard the grumbling, but remained impassive; at the next stop, a kind word and improved rations were enough for the cry of “Vive L’Empereur (Long live the Emperor)” to rise once again, as powerful and sincere as ever. Veterans of the Republic’s wars, who had seen much worse, sometimes found their situation so unbearable that they committed suicide, as was notably the case in Spain, in the mud of Valderas.

To be more mobile, the imperial army did not use tents. At bivouacs, soldiers slept on the ground under the stars, or on straw when they found some in a barn. If needed, they protected themselves by building makeshift huts from branches. When their stay was prolonged, the ingenuity of French soldiers took over, and temporary barracks sprang up, lined up as neatly as the houses in a village. The English admired these constructions in 1814 during the fighting in the Pyrenees.

In towns, lodging billets were distributed; the designated host was required to provide food and shelter. The good-natured Germans were the most appreciated of these unwilling hosts (and it was said, Germans, not Prussians). The soldiers’ meals were improved by the presence of “cantinières” and “vivandières” who provided brandy; their presence comforted the warriors if not rested them.

Unenviable Fate of the Wounded and Dead

After battle, the dead were not buried. The wounded were treated only with significant delay, and some were even forgotten where they had fallen. During the retreat from Russia, survivors were found still alive a month and a half later on the battlefield of Borodino! One of them had sought refuge inside the belly of a dead horse; half-mad, he shouted violently at the Emperor. Amputations were frequent, often the only way to save a wounded man’s life. These operations were performed without anesthesia, with the patient given a glass of brandy, if available, and a pipe to smoke. The phrase “to break one’s pipe” originated from these times, referring to the pipe-breaking when a surgery went wrong.

Hospitals were vast death-traps where the sick and wounded were thrown together, often on the ground. Such close quarters facilitated epidemics, and corrupt hospital administrators sometimes deprived the unfortunate patients of food and fuel to sell them for profit. During the winter of 1813-1814, more soldiers of the Grande Armée died from disease than in the battles of 1813. This was not a new phenomenon; the same had happened in Spain!

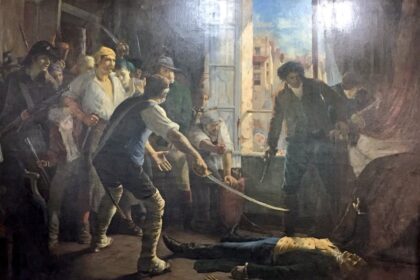

The fate of those who fell into enemy hands was even worse. In the Iberian Peninsula and Russia, they faced the risk of being executed after enduring horrific torture. In Russia, fanatical peasants would beat them to death with sticks. In Spain, they were tortured to death in grotesque ways: made into sandwiches, roasted like chickens, boiled like lobsters, fried like fish, or smoked like hams. They were poisoned, sawed between planks, castrated, buried alive up to their heads with their hands cut off so they could not free themselves.

Prisoners of the English were crammed into half-rotted ships, the infamous floating prisons known as “hulks,” or were deported to the deserted island of Cabrera in the Balearics, where many died of thirst and hunger. It would take an entire book to describe what these unfortunate souls endured, in conditions that foreshadowed the concentration camps of World War II.

The Emperor and His Soldiers

In the French army of this era, corporal punishment, still common in other European armies, was forbidden. It was considered degrading. For the most serious offenses, only one punishment was deemed worthy of a soldier: execution by firing squad. This was the punishment demanded by French prisoners in England who had been flogged. Marbot, sent as an emissary to the enemy camp, saved a French prisoner from a beating at the hands of the Prussians during the 1806 campaign.

He warned the Prussian officers that if the Emperor learned that they had inflicted such a punishment on one of his soldiers, all negotiations would cease, and the King of Prussia would no longer reign.

Napoleon demanded such heavy sacrifices from his soldiers that one wonders how they not only endured it but also developed a genuine devotion to him. The answer lies in a few simple words, expressed by one of them: the Emperor brought dignity to these men, most of whom came from the lower classes. While he did not tolerate familiarity from his marshals—except in rare cases, due to court etiquette, with Lannes being almost the only one to address him informally—he tolerated and even encouraged it from his rank-and-file soldiers, whom they called “the little corporal.”

Gifted with an extraordinary memory, he remembered their names and reminded them of the places where they had fought under his command. He affectionately tugged their ears and even once stood guard at the Tuileries Palace in place of a sentry he had sent for a drink to warm up. He laughed at their witty remarks. Shortly before the Battle of Austerlitz, a sentry responded with humor when Napoleon, annoyed by an arrogant Russian envoy, shouted, “Wouldn’t you think these fellows want to devour us!” The sentry retorted, “Oh, but we’ll stick in their throats!” This remark brightened the Emperor’s mood.

The soldiers did not hesitate to analyze and criticize what they believed to be their general’s strategy, even at the risk of reprimands when they overstepped. This happened at Jena, when a young soldier impatiently shouted “Forward” at Napoleon’s passing. The Emperor replied that he should wait until he had fought in a hundred battles and won twenty before offering advice.

The Emperor placed such great trust in his men that, on the eve of the Battle of Austerlitz, he revealed his plan to them—an event unique in the annals of war. After a battle, he sometimes asked the infantry of distinguished units to nominate the bravest among them for a reward, and he once pinned his own Legion of Honor on the jacket of a worthy soldier. In short, Napoleon understood the psychology of his soldiers and mastered the art of inspiring their enthusiasm.